In November 2011, the Bloomberg news agency revealed how French software company Qosmos SA, one of France’s leading experts in the most advanced internet interception technology known as Deep Packet Inspection, was sub-contracted by German firm Utimaco, itself sub-contracted by Italian company Area SpA, to provide Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad with a mass surveillance system with which to spy on his opponents.

Bloomberg described the technology the three firms were supplying to the Damascus regime, in a project codenamed Asfador, as having “the power to intercept, scan and catalog virtually every e-mail that flows through the country”. At the time of the Bloomberg report, the civil war in Syria had been raging for nine months and had already claimed an estimated 3,000 lives.

Questioned by Bloomberg in November 2011, Qosmos CEO Thibaut Bechetoille said the firm had decided to pull out of the Syrian project four weeks earlier. “It was not right to keep supporting this regime,” he said. The company insisted that the tools it had supplied were not, when it ended its involvement, in an operational state and underlined that it was subcontracted by Utimaco and had never directly sold material to the Syrian regime.

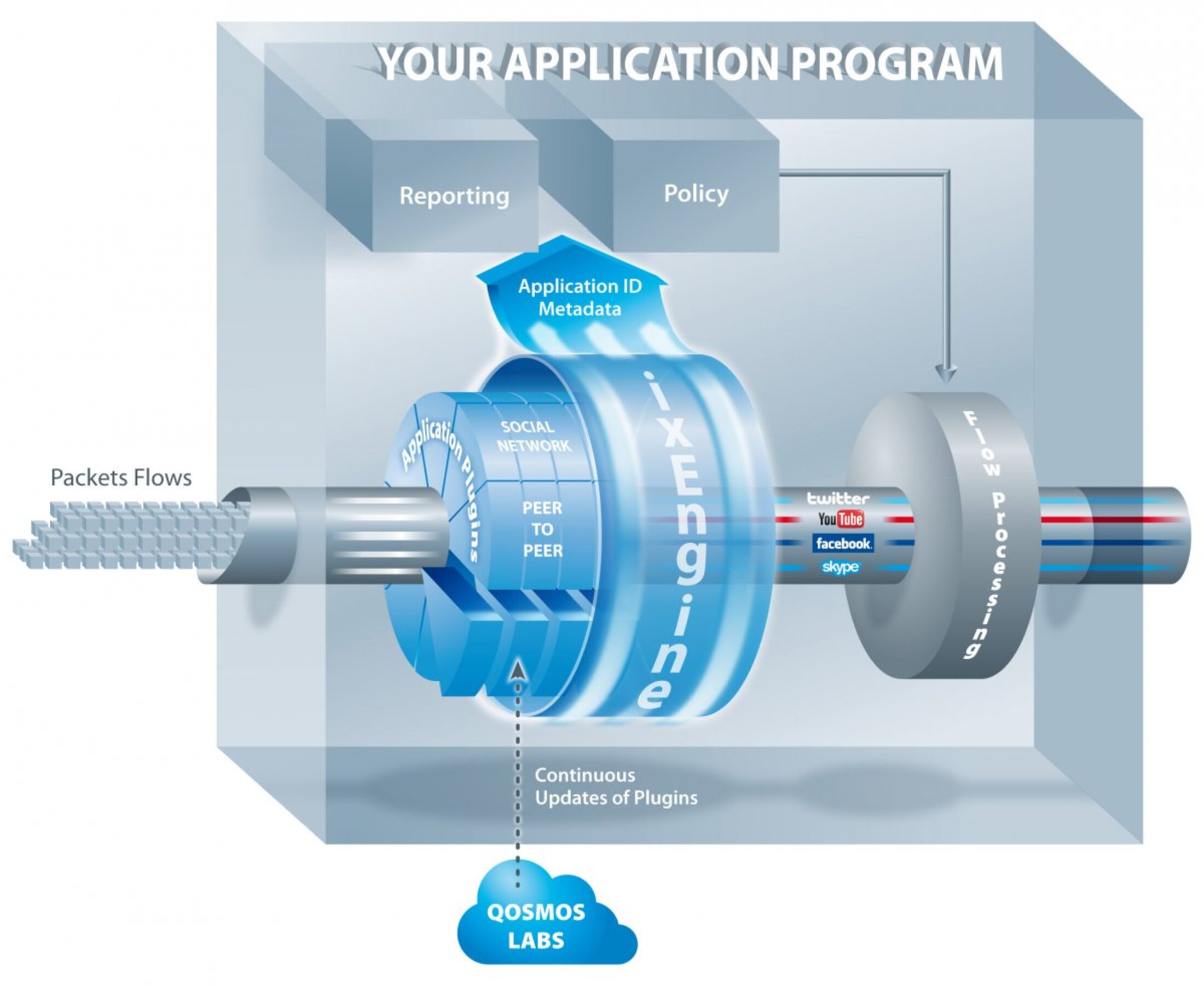

Enlargement : Illustration 1

But this joint investigation by Mediapart and French website Reflets.info has learnt that the Qosmos spy tools, called ‘probes’, were installed in the Syrian regime’s surveillance system, and could well have been used by Damascus despite the French firm’s exit from the project. It has also established that Qosmos continued to work for Utimaco at least until November 2012. While this continued cooperation may have had no link to Syria, it gave the German company access to updated and improved Qosmos technology which could have potentially be used for the probes Qosmos supplied for the Asfador programme.

In July 2012, the French League for Human Rights (LDH) and the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) sent a letter to the Paris public prosecutor’s office in which they alerted it to the involvement of Qosmos in the Syrian project and demanded the opening of a judicial investigation into the matter. In their joint letter, the rights organisations said Qosmos “has been on several occasions, and according to different sources, accused of having contributed to the supplying of the Syrian regime with electronic surveillance equipment necessary for the repression of the rebellion that has been happening in Syria since March 2011”.

In a statement to Mediapart (see text bottom of page 4), Qosmos said it "wishes to strongly deny – as we have never ceased to do – the false and scurrilous allegations which we have been the object of over several months,” adding that it had launched a lawsuit for defamation against The LDH and FIDH.

In April this year, a judicial investigation was opened into Qosmos’ suspected involvement in ‘complicity in acts of torture’, led by three magistrates from a dedicated ‘War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity’ judicial investigation branch based in Paris.

They must establish whether or not the material supplied by Qosmos for Asfador was operational and whether the company knew, when entering into the contract, that its technology was to be used by a dictator to identify and detain opponents.

The origins of the French firm’s collaboration with Utimaco go back to 2009, when Qosmos had become recognised worldwide as a leading specialist in Deep Packet Inspection. In October of that year, the company released a statement announcing: “Qosmos, the industry leader in network intelligence technology and Utimaco, a leading global provider of lawful interception systems, today announced that Utimaco has chosen Qosmos ixMachine for its LIMSTM (Lawful Interception Management System) solution. With ixMachine probes, Utimaco, a member of the Sophos Group, is able to strengthen its Lawful Interception solution with a deeper level of information extraction than before, thanks to ETSI-compliant Qosmos probes that deliver higher throughput and easy integration within existing network environments.”

It was shortly after that contract was signed that Qosmos staff began working on the Asfador project. Qosmos says it sells what is just one part of a far larger surveillance system. In fact, its probes provided a key part of the surveillance architecture: in short, they filter communications and transfer them into a massive database from which a file of communications concerning any individual can then be consulted by simply entering a name or an email address. A larger file can be built that includes that individual and the persons he or she has communicated with, forming a tree of targeted individuals and their correspondence.

A tardy realisation of probes' purpose

Qosmos' probes can be used for surveillance at a national level, or within network hardware such as routers which direct packets of data between internet networks. “Qosmos develops network intelligence technology, providing real-time visibility into data as it crosses networks,” reads the French firm’s presentation of itself. “The company’s software development kit and hardware platforms are used by systems integrators, solution developers and network equipment suppliers to make their applications more secure, efficient and profitable. Qosmos network intelligence technology enhances solutions for lawful interception, cyber security, traffic optimization, QoS management, content billing, market research and more. “

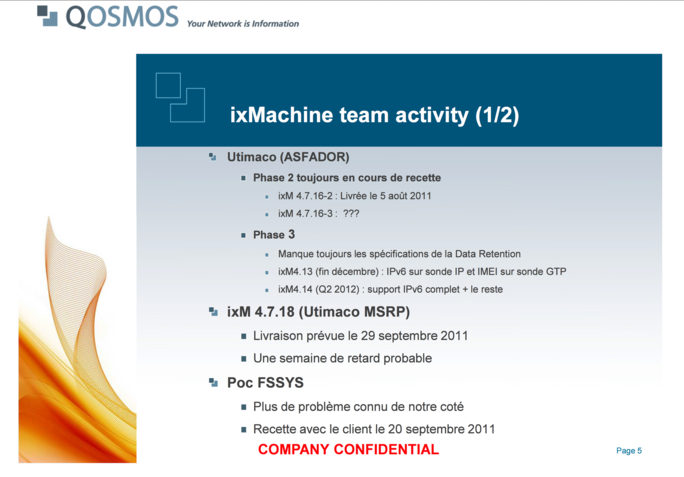

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Most of the time the company works as a subcontractor, rarely working directly with the end-client. But that does not prevent it from knowing what use its equipment will serve. Already, the customer’s technological demands provide a good indication of this, and only a limited knowledge of world affairs is needed to judge a country’s democratic status. The company’s decision to withdraw from the project in October 2011 for what Qosmos CEO Thibaut Bechetoille said were ethical considerations could have been reached earlier, when it was known that Syria was the end-client – and which in effect would have been apparent shortly after the contract was signed.

To understand the field of the company’s activities, it is necessary to understand what Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) is. DPI is in itself neither good nor bad, it depends what you use the technology for. If one were to think of the internet as if it was a road network, with its toll booths and traffic jams, DPI can be used as a police car with the power to re-direct traffic, stop your vehicle, take it apart and block it. Where this comparison with a police car ends is with the fact that DPI is a massive, systematic entity, and almost infallible – as long as it’s placed on the right road. It is as if every vehicle was stripped and put back together again without the occupants even realizing. In the case of the Syrian internet system, run by the dictatorship’s Syrian Telecom Establishment, all the roads arrive at one and the same place.

In 2009, SOFRECOM, a subsidiary of French telecommunications giant Orange specialized in telecoms engineering, was engaged by Syria to help the Syrian Telecom Establishment (STE) modernize its network. It was just one of several contracts the company had with states which have shown scant or inexistent regards to human rights, including the Gaddafi regime in Libya, Vietnam, Thailand, Ivory Coast, Ethiopia and Chad.

The extent of collaboration of French communications technology firms with foreign dictatorships – such as Amesys, a subsidiary of French IT company Bull, which provided former Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi with technology to spy on emails and chat forums, and telecom engineering company Alcatel (now Alcatel-Lucent) with the regime in Myanmar (Burma) – raises doubts as to whether these contracts are urged along by government for intelligence purposes, with the benediction and help of other allies. Whatever, it is difficult to imagine that the French authorities, at the highest level, were unaware of the involvement of Qosmos in the Syrian project, given the company’s very close links to French intelligence, and for which a number of its activities are protected by France’s all-powerful ‘national defence secrecy’ clause of confidentiality.

When Qosmos CEO Thibaut Bechetoille told Bloomberg in November 2011 that his firm had decided to pull out of the Syrian project four weeks earlier, the company’s marketing director, Erik Larsson, told the US news agency that “the mechanics of pulling out of this, technically and contractually, are complicated”.

It remains that if a decision was taken by Qosmos to exit the contract in October 2011, the uprising in Syria and its bloody repression by the Damascus regime had begun seven months earlier. According to information gained by Mediapart, Qosmos probes were among the equipment for Asfador installed in Syria during the summer of 2011. In all, between five and ten servers to be used in the internet surveillance system were installed.

The Asfador project was never the subject of a specific contract with Qosmos, and similarly there is no written trace of a decision by the company’s board to end it. However, following a request by Qosmos, Utimaco issued a statement in July 2013 in which it confirmed that Qosmos had stopped supplying its probes in November 2011, and that these were not at the time operational.

Tools to update the probes

But to what degree the probes were not operational is unclear. Mediapart has gained access to a confidential internal document prepared by Qosmos, dated September 8th 2011, which shows that by then phase two of the project had reached validation stage. This is when the client and supplier carry out a series of tests to ensure everything is working properly, and which indicates that the work was in a considerably advanced state. The document (see immediately below) cites a forthcoming phase three.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

At that time, the infrastructure sold to the regime of Bashar al-Assad was not operational in the sense of being activated to begin mass surveillance of the Syrian population. In the internal document, Qosmos indicates that the probe for capturing communications on mobile phone traffic (using the GTP internet-based protocol) would be delivered on December 29th 2011 (as part of phase three).

It also says that it will deliver its spyware for Message Session Relay Protocol, which is used for instant messaging and multimedia exchanges on mobile phones, on September 29th 2011. Another document says technical information about both of the above would be delivered in May 2012.

A Qosmos engineer told Mediapart that he believed that at that moment the project was not operational because the company had difficulties in mastering the technology needed for such a vast system. “There is sometimes a gap between the boxes that you tick during the call for tenders, to get in there, and what you can really do,” he said. However, in the opinion of other employees contacted for this report, the project may have been partially operational, at least in the sense that the Syrian regime could later activate it after receiving software updates and corrective information.

The problem in establishing the truth of the situation in the autumn of 2011 is that the Asfador project was not the subject of any specific contract with Qosmos; it was one aspect of the firm’s partnership with Utimaco, which lasted up until the end of 2012.

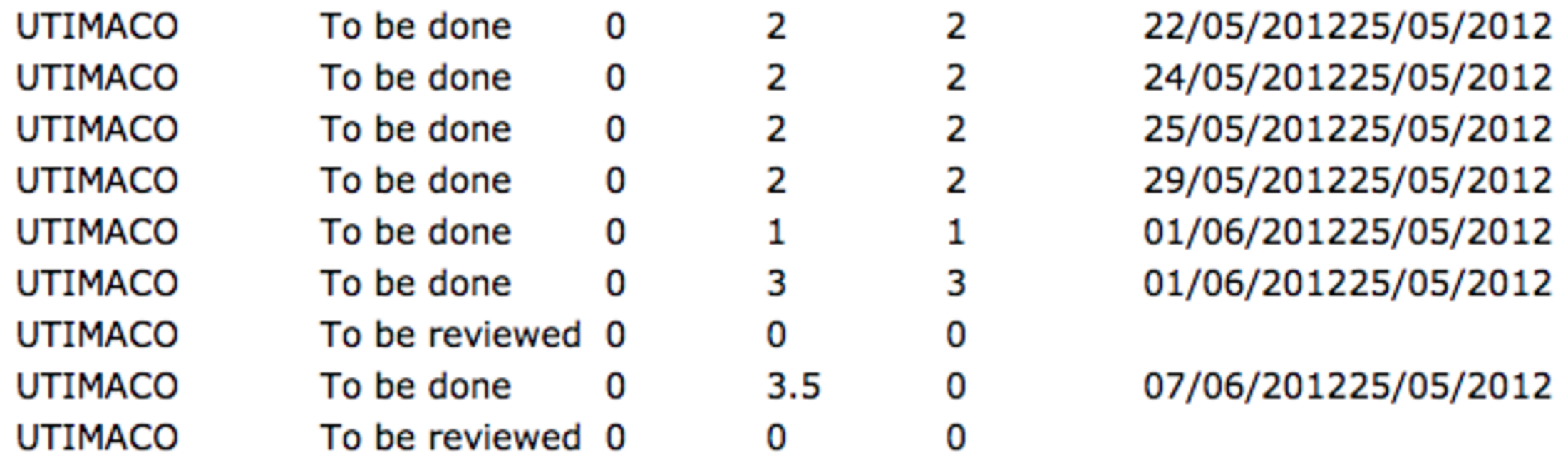

Enlargement : Illustration 4

According to other Qosmos documents obtained by Mediapart and Reflets.info, Qosmos continued to supply Utimaco with its products after abandoning the Asfador project. In a report established during the first quarter of 2012 (see above) summarizing the progress of numerous contracts underway at the French firm, the name of Utimaco appears on several due for delivery in May and June 2012.

While Qosmos and Utimaco may have been working on projects unconnected with that in Syria, the German company had direct access to the French firm’s updates of its technology for mass surveillance systems. To update the probes which Qosmos supplied for the Asfador programme there was no need for ‘deliveries’ in the traditional sense of the term. Instead, Qosmos clients are given access to a dedicated website from where they can download updated, improved software, and according to documents consulted by Mediapart and Reflets.info, the French firm did deliver to Utimaco improved versions of its mass surveillance tecnology – although the codename Asfador is not mentioned in the process.

While Qosmos CEO Thibaut Bechetoille insisted that his firm’s probes were not operational in Syria, Qosmos continued to make available information on the procedures to be followed to set up the probes, notably concerning the protocols that the STE had specifically requested, nine months after Bechetoille said it had pulled out of the contract.

It is possible that the information was provided for other clients of the systems provided by Qosmos and Utimaco. Mediapart understands that the Qosmos management had mentioned Canadian and Australian end-clients for the systems. However, among all Qosmos staff questioned during this investigation none had knowledge of any other client than Syria in the mass surveillance projects that were part of the company’s partnership with Utimaco.

An unusual vision of 'Lawful Interception'

What appears certain is that despite underlining its sub-contractor role with Utimaco, Qosmos knew very well when it undertook the work on the Asfador project what use would be made of its probes by the Syrian regime. From the very beginning, the aim was clear: beyond the surveillance of the internet network, the French company was to deliver probes capable of intercepting mobile phone calls, the geolocation of mobile phone users, voice analysis, to take over control of computers and even to launch cyber-attacks.

In September 2013, following the publication of information on Spy Files 3 on the Wikileaks website, a journalist with French news website Rue89, Jean-Marc Manach, reported how a Qosmos employee had travelled to Damascus in January 2011. Qosmos told Manach: “A Qosmos engineer travelled to Syria in January 2011, as a sub-contractor for the Utimaco company, which was itself a sub-contractor for the company Area. This sojourn consisted of technical meetings with the operators in a framework of initial studies of the project.”

This investigation understands that the engineer who travelled to Damascus was Sébastien Synold, the current head of the Qosmos office in the US. He could not have been unaware of what his company’s equipment was about to be used for. He knew that the end-client was STE, and what were its espionage aims given that there is a clear difference between requirements for measuring web traffic and that of mass surveillance of communications.

The tools referred to in the internal Qosmos documents regarding its partnership with Utimaco are those of “Lawful Interception”. The term Lawful Interception sits oddly with a mission to collect the identities and passwords of Syrian internet users, to read their emails and to discover which websites they visit.

Invited to respond to the issues raised in this article, Qosmos replied with a statement sent by email. “Qosmos wishes to strongly deny – as we have never ceased to do – the false and scurrilous allegations which we have been the object of over several months,” the company wrote. “Indeed, we reiterate that not one piece of our equipment or software was operational in Syria. We wish to underline that we have, as of September 2012, launched a lawsuit for defamation against the FIDH [International Federation for Human Rights] and the LDH [French League for Human Rights]. As for the rest, a judicial investigation is ongoing, we reserve our response for the justice authorities.”

-------------------------

The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse