In late 2012, when ArcelorMittal trade unions were still trying to find a buyer for Florange, the plant in eastern France that the steel conglomerate finally closed in April, they were discreetly given a sheet of paper that detailed how the fortunes of the group's flagship European flat steel business had dramatically reversed under Mittal's ownership (1). It was unsigned, but probably came from a manager who was conversant with how the company operates and unhappy with what he was witnessing.

It consisted of a table showing how the business had swung into the red in 2008 from a 2007 profit of 112 million euros, and a note in which the anonymous writer added: “This can be likened to a transfer of ArcelorMittal France's business assets to Luxembourg.” Mediapart asked ArcelorMittal if the figures were a true reflection of reality, but received no reply.

The unknown author concluded: “We can also see that a nationalisation of Florange or the French business would be a catastrophe for Mittal. As the profits are syphoned off, and as any indemnity would be based on a valuation of current profits, [the compensation] would be very low (…) France could today buy ownership of the entire French steel-making operation for a sum equal to the amount of back tax owed.”

Enlargement : Illustration 1

This is probably a rough and ready assessment. But as Europe rightly frets over the future of its steel industry, which remains a strategic sector despite the current difficulties, it raises an important question. Why have ArcelorMittal's results in Europe been so poor in good times as well as bad? And how long will European governments tolerate the lack of transparency at the world's largest steel maker?

The European flat steel business is at the heart of Lakshmi Mittal's strategy. As soon as the 2006 merger between Mittal and Arcelor had been completed, his son, Aditya Mittal, was put at its helm.

Arcelor had made this business central to its strategy during a global steel price war. It had sought to improve its competitive position by focusing its research efforts in precisely this area, aiming to produce ultra-high-value-added steels for the car industry and for domestic appliances.

And it succeeded. It managed to turn its coated and uncoated ultra-thin steel sheets into brands at the point of sale, as if they were consumer goods rather than semi-finished industrial products. Its customers are still prepared to pay a premium for goods of such quality.

Yet according to the merged company's published results, this business is one of the least profitable in the group, and was even struggling as steel prices hit historical highs in 2008. That year, contrary to his promises during the bid battle, Lakshmi Mittal took over operational control of the company and the group’s new structure was put in place.

-----------------------------------

1. In 2006 Mittal Steel bought Luxembourg-based Arcelor, which had been forged by merging French, Belgian and Spanish steel makers in 2002, after winning a hostile takeover bid.

Vanishing profits, exploding financial costs

Enlargement : Illustration 2

According to its annual report, ArcelorMittal's European flat steel business had a turnover of 27 billion dollars in 2008, 23.7% more than in 2007. The anonymous table gave a figure for 2008 gross operating profit, or EBITDA (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation), of 4.3 billion euros, or around 6 billion dollars, but this figure has never been supplied by the company. If it is accurate, it implies a healthy gross margin - ratio of gross operating profit to turnover - of 22% for the European flat steel business.

Under accounting rules, calculating EBITDA involves deducting normal production costs such as purchase of raw materials, salaries, transport and so on, but no financial costs are subtracted at that stage. So it is puzzling that the 2008 operating profit Mittal published for the European flat steel business was only 2.5 billion dollars, 19% less than in 2007. The group did not explain the fall.

As a direct result of this, ArcelorMittal's 2008 tax liability was substantially lower than in 2007, dropping from 3 billion dollars to just 1 billion dollars, although the whole group made a profit of 10.4 billion dollars, little changed from 2007. “This represents a tax rate of 9% against 20.4% in 2007,” the company noted with approval.

Similar engineering was applied to the French subsidiary, according to the figures given in the anonymous note. Atlantique et Lorraine, the French flat steel unit, accounts for 22.8% of flat steel production in France. But in 2008 it contributed only 6.5% of group EBITDA according to ArcelorMittal's accounts, and its profits simply vanished. So just as steel prices hit record highs, the French plants that specialised in making the highest value-added products were apparently losing money.

For a long time this paradox did not worry the tax authorities unduly. During this period Christine Lagarde, France's finance minister from 2007 to 2011, was regularly invited aboard Lakshmi Mittal's yacht when it anchored off the Corsican coast in the summer, though there is no suggestion that the minister’s actions were influenced in any way by this hospitality.

The key to understanding how ArcelorMittal's European plants, and in particular its French operations, could suffer such a reversal of their profits despite having strong operating results lies in the opaque organisation Lakshmi Mittal set up when he took control of Arcelor. It would seem no stone was left unturned in a quest for fiscal optimisation and ensuring each financial transaction fed the Mittal family's coffers.

Since the merger the company has embarked on a voracious expansion policy, buying up coal and iron ore mines and blast furnaces across the globe. This involved heavy borrowing, and the group's debts stood at 22 billion dollars at the end of 2012. That implies mushrooming financing costs.

In 2008 ArcelorMittal's financial charges surged a staggering 154% to over 3 billion dollars. Since it is not clear how this is accounted for across the group, Mediapart asked for clarification. However, the company did not reply to our questions on how borrowings and financial charges are apportioned between the parent company and its subsidiaries.

The anonymous note, however, did reveal how the system works. The writer describes a mechanism of vertical integration and a policy of transfers to Luxembourg to a company he calls A, then continues: “But company A has borrowed heavily from another Mittal subsidiary, company B, situated in Dubai in a free zone. So company A pays vast sums of interest to company B, which does not pay tax.”

The plethora of Mittal's offshore subsidiaries

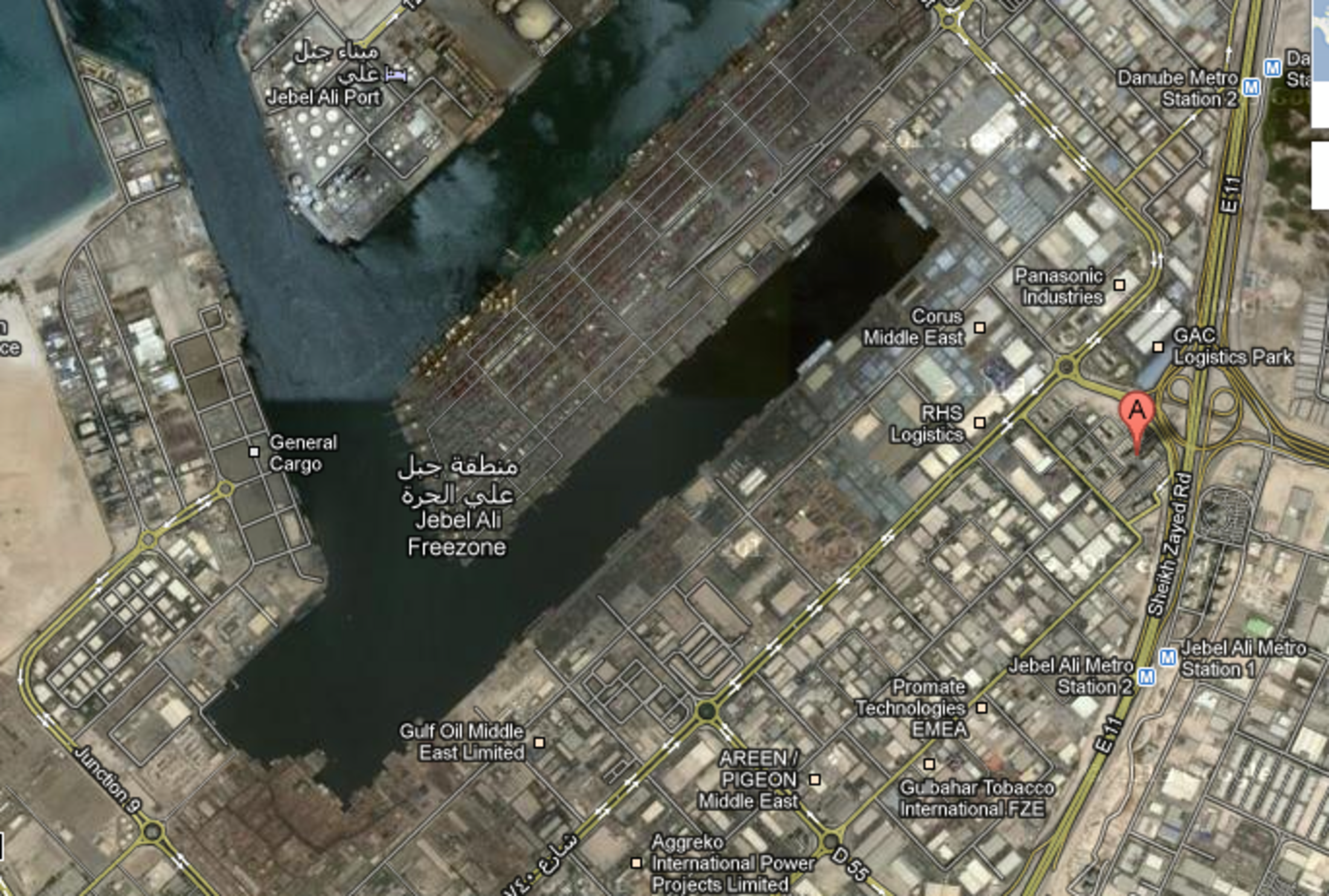

So how does Mittal's Dubai operation work? Just after the merger ArcelorMittal set up a new subsidiary, ArcelorMittal International FZE, based in the Dubai tax-free zone. Officially it specialises in international trade and major infrastructure projects – multinationals often use this type of separate structure for signing certain international contracts, as Mittal did with Nigeria.

In fact the subsidiary would appear to be simply an offshore company located in a tax haven. Despite the work officially assigned to it, fewer than ten people actually work there, and all of them have Indian nationality, according to the Dubai free zone directory available on the internet.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

But the base in Dubai has a dual role. ArcelorMittal says in its annual report that one of its financial centres was transferred there from Belgium. And for the purposes of reducing its tax burden, it is obvious why. European countries could never offer the same conditions as Dubai no matter what they did, as companies in the zone simply pay no tax at all. And unlike in Belgium, companies in Dubai are protected from any requirement to provide information.

In fact it is not clear whether ArcelorMittal International FZE is the group’s financial centre, or whether this role is played by one of two other subsidiaries also located in Dubai, LNM International or LNM Global IT Services. “Before its purchase of Arcelor, the group used these structures as transit points for charges imposed on each of its subsidiaries on steel sales,” says a source familiar with the company.

These two subsidiaries, named with Lakshmi Narayan Mittal's initials, belong to the Mittal family. They are controlled by another offshore company, Richmond Investment Holdings Ltd, based in the British Virgin Islands, where the Mittal family has parked part of its fortune since its beginnings with Ispat. And the Virgin Islands are a secretive tax haven under British jurisdiction, so absolute discretion is assured.

From this point the Mittal family smokescreen makes any further information impossible. Everything is hidden in the sands of Dubai. There are no official accounts for any of these subsidiaries, so it is impossible to see how they work, how much money transits through them and what the group pays for their services. Some suggest the family has set up a debit system based on the difference between an official financing rate granted to the parent company and the rate actually paid, but no one actually knows.

The only recourse is to put questions to the company that it has no interest in answering. But it is clear why Lakshmi Mittal put his youthful son in charge of the group's finances: business secrets are kept in the family.

If the descriptions of ArcelorMittal's system are accurate, the Mittal family has nothing to gain from bringing its high debt levels under control. It wins whether the company is in good health or not. The company's auditors and independent board members do not seem unduly worried, although the Mittal system operates to the detriment not only of nation states, but also of other shareholders. Lakshmi Mittal owns 39.9% of ArcelorMittal’s capital but acts as if he were the sole shareholder. Yet the British press, which backed Mittal against Arcelor management during the bid battle, repeatedly extolled the supposed virtues of Mittal's governance.

Richest man in Britain

ArcelorMittal under Lakshmi Mittal is clearly ailing, paying a high price for an uncontrolled, debt-financed expansionist policy and tax evasion. But even as the company struggles, Lakshmi Mittal himself is doing spectacularly well. It has taken him fewer than 20 years to become the richest man in Great Britain with a fortune estimated at more than 10 billion pounds, or some 11.7 billion euros – a tidy sum even if it has been trimmed back by the fall-out in ArcelorMittal's share price.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Despite this, Lakshmi Mittal, who is well-liked in British political circles and in particular by former prime minister Tony Blair – Mittal has contributed substantial funding for the Labour Party in the past – pays practically no tax in Great Britain either. According to The Daily Telegraph he negotiated a flat-rate annual payment of 50,000 pounds, or some 58,530 euros, with the Inland Revenue, the British tax authority, because of his 'non-domicile' status.

He owns a house in one of London's top-notch neighbourhoods valued at 57 million pounds, or some 66 million euros, but he does not pay local or property taxes on that either, because he transferred ownership to a UK-based company which pays those taxes for him. The British government is beginning to recognise, a little on the late side, the Mittal instinct for fiscal optimisation that the Luxembourg government has learnt to its cost.

“Lakshmi Mittal presented himself as a man who came from nothing and built a steel manufacturing empire single handed: a fabulous success story (...),” Philippe Lukacs, professor of strategy at Ecole Centrale de Paris, wrote in an opinion piece in Le Monde in January. “In our ethnocentric way we saw only an Indian family, and in particular a Hindu one, functioning traditionally in line with a specific family path.”

He continued: “We have not paid attention to the fact that Mittal belongs to a line of descendants who all originated in Rajasthan [in north-west India]...These are the descendants of shopkeepers and lenders. Their dharma, their duty, their 'vocation' is to become rich.”

At the start of January ArcelorMittal, heavily in debt and with a 'junk' credit rating, was forced to raise 3.5 billion dollars (about 2.7 billion euros) through the issue of shares and convertible notes. The Mittal family itself pumped 600 million dollars into buying these shares and notes. It certainly owed the group that; since the fusion of the two firms the family has taken out more than 6 billion dollars in dividends, without counting the share buybacks carried out by the group. But at the same time the family also took some precautions. Half of the money went towards buying shares but the other half purchased various convertible bonds with a rate of interest between 5.8% and 6.3%. This is a good return at a time when interest rates bring in under 1%. Moreover, despite its colossal losses, ArcelorMittal continues to pay dividends.

The Mittal family carried out this operation using an array of companies in which the control of the group ultimately rests. All are based in tax havens. Lumen Investments and Nuavam Investments, which directly hold ArcelorMittal shares, are based in Luxembourg. They are in turn controlled by a Gibraltar-based company Grandel Limited which in turn is controlled by the Platinum Trust and the Silver Trust registered in Jersey.

At the start of April the Mittal family took an important decision: all the shares of the Luxembourg-based companies that contain the family's holding in ArcelorMittal will no longer be denoted in euros but in dollars. So at the very moment that Lakshmi is asking for support from Europe, he appears to be considering heading off to new pastures that are even more discreet.

-----------------------------------

English version by Sue Landau

Editing by Michael Streeter