When the European Union floated the idea of refugee centres in North Africa to screen prospective migrants in June, the Tunisian ambassador to the bloc gave a curt reply. “The proposal was put to the head of our government a few months ago during a visit to Germany, it was also requested by Italy, and the answer is clear: no!”

Tahar Chérif was one of the first to react to the EU's recent attempts to shore up its migration policy, which is contested both by countries seeking to stop migrants coming to Europe and by those who prioritise migrants' safety. Earlier in June, Malta and Italy refused landing to the Aquarius, a boat carrying African migrants, and the bloc is now scrambling to find solutions to hold its diverging members together on the issue.

But this time there was no question of Tunisia acceding to another European ploy to re-locate refugee camps beyond its borders, this time to the Maghreb, and least of all to a fragile country such as Tunisia, the only one whose Arab Spring has yielded a path towards democracy. “We have neither the capacity nor the means to organise these detention centres. We are already suffering a lot from what is happening in Libya, which has been the effect of European action,” Chérif said in an interview with Belgian daily Le Soir, quoted in The Guardian.

In 2016 the EU struck a controversial deal with Turkey on migration after surge of refugees to the continent in 2015. It has also been training the Libyan coastguard to intercept migrants, exacerbating overcrowding and inhuman conditions in camps in Libya, which has become the migrants' main transit point.

After the furore over the Aquarius, Brussels is again turning to the idea of externalising its borders to the other side of the Mediterranean. The president of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Junker, and Filippo Grandi, the High Commissioner of the United Nations refugee organisation, UNHCR, both support the plan. But the countries bordering Libya were not even consulted (see Mediapart's interview in French with Moroccan sociologist Mehdi Alioua here).

The experience of Choucha camp, located in south-eastern Tunisia not far from the Libyan border, is a salutary reminder for Tunisia of how such a policy can turn out. UNHCR and the Tunisian authorities opened the camp in February 2011 as an emergency response to an influx of hundreds of thousands of civilians fleeing the war in Libya. It has come to symbolise the failure of transit and integration of refugees in a country without the resources to cope.

In 2013 UNHCR deemed its mission finished and closed the camp, leaving hundreds of people whose asylum claims had not been accepted stranded in appalling conditions. The camp, which ultimately housed more than 20 nationalities, sits in a scorching desert with no water or electricity. Its current inmates – about 700 of them – stay rather than return to the hell of Libya or their countries of origin. A year ago 40 or so were taken to a home for young people in Marsa, near Tunis.

“This idea of detention centres suggested by Brussels is very worrying for Tunisians. The situation in the Coucha camp has been so complex, the clashes so violent, that the population is on edge,“ said Valentin Bonnefoy, of the Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights (FTDES), the main association on migration issues in the country. “Coucha camp showed that Tunisia was not prepared to take in vulnerable people given its economic and social situation.”

Tunisia, itself a source of emigration to Europe but also a destination for immigration and transit, is resisting European pressure as far as it can. It has been negotiating a 'mobility' partnership with the EU for the past four years, under which the bloc would facilitate granting visas to Tunisians – at least for the categories it chooses, like top managers, professionals, academics, businessmen, when those who are prepared to die at sea are above all those who eke out a living at the bottom of the social scale.

The other side of the deal would involve Tunisia working against 'illegal' immigration and agreeing to take back unauthorised Tunisians from the EU. But it would also have to take back undocumented third party nationals who arrived in Europe via Tunisia, which it refuses to do.

And since the start of this year Tunisia, a country with a functioning democracy but which suffers from high youth unemployment, even among the most qualified, has seen a spectacular resurgence in emigration to Italy, in particular to Sicily and the island of Lampedusa. This is not a phenomenon on the same scale as in 2011, when former President Zine el-Abdidine Ben Ali was ousted and security measures were relaxed. At that time, more than 30,000 people made the journey, not counting those who died or disappeared at sea.

It is nevertheless a significant exodus. “Tunisians are the second [most numerous] nationality to arrive in Italy after Eritreans, while in 2017 they were eighth,” said Bonnefoy of FTDES. This can partly be explained by the sharp fall in departures from Libya after a secret accord between Rome and Libyan people smugglers in 2017, which overwhelmingly affected migrants from sub-Saharan Africa and Bangladesh.

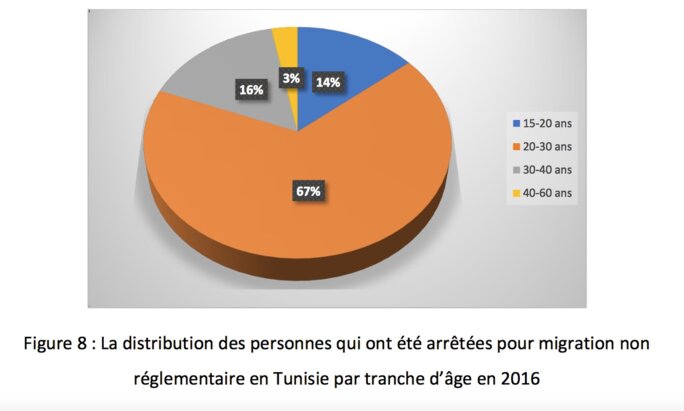

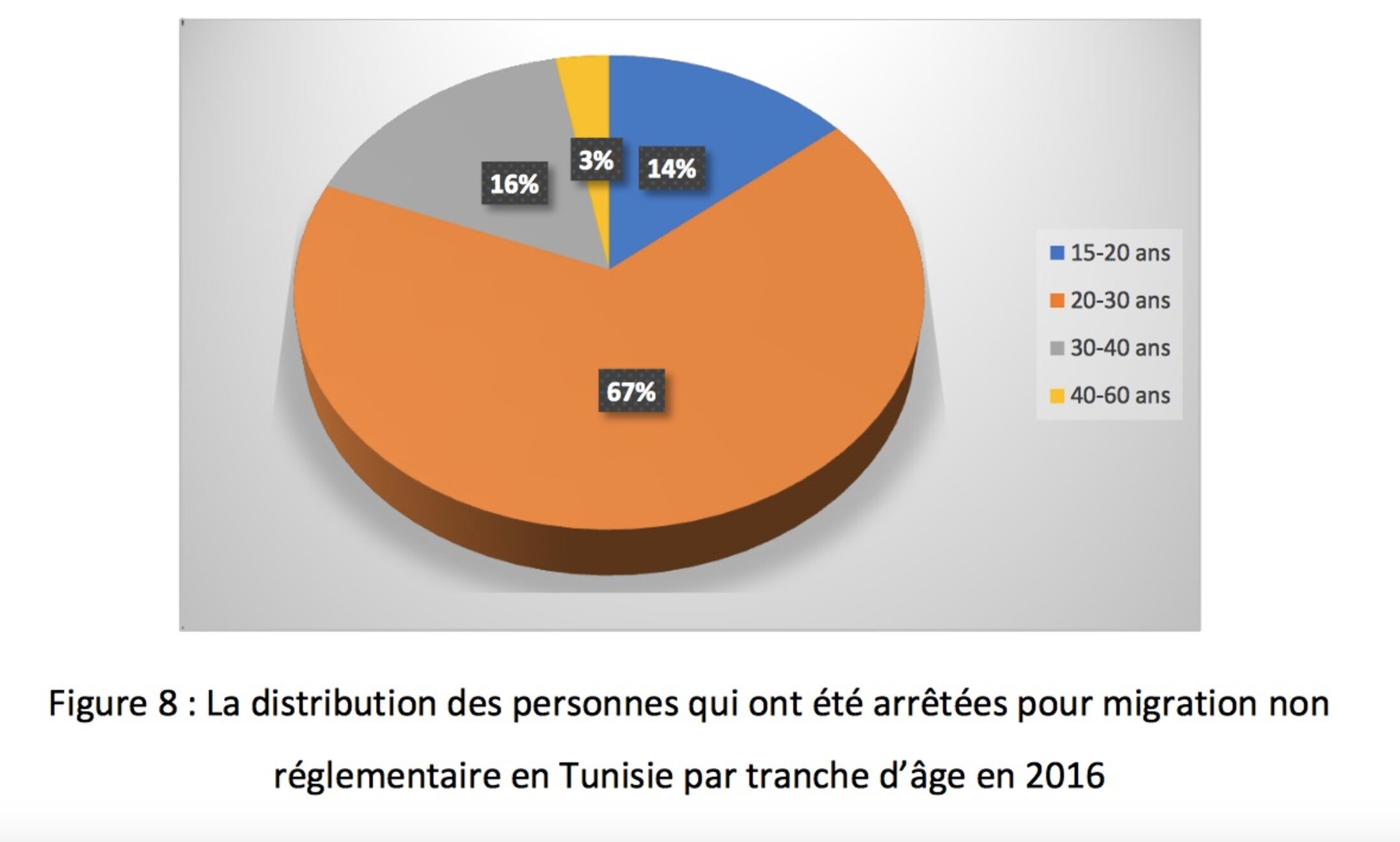

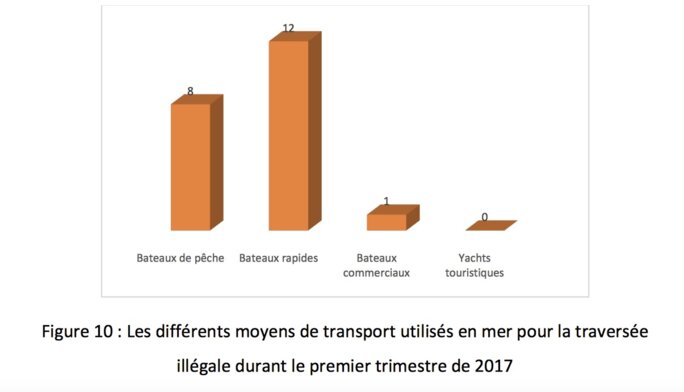

Of the tens of thousands who crossed the Mediterranean to Europe from January to April, 1,910 were Tunisian, the third most numerous nationality after Syrians and Iraqis, according to figures from the International Organisation for Migration (IOM). FTDES’s own figures are based on the number of migrants intercepted by the Tunisian authorities at the time when they leave the Tunisian coast, plus those arrested in Italy and expelled to Tunisia. The organisation warns that those figures understate reality, as they do not include those who make the journey and slip away.

Migrant shipwreck has aggravated the political crisis

Over June to October last year, when the wave of migration from Tunisia was already ramping up, FTDES counted 3,178 Tunisians arrested by the country's coastguards and 6,151 who arrived in Italy, but average estimates suggest some 15,000 departures, whether successful or aborted, Bonnefoy said. By the beginning of June this year, 5,900 attempts to leave had been stopped by the Tunisian authorities, he added. He also noted that Italy had resumed expulsions of migrants. Last year it expelled 2,193 Tunisians, 36 percent of the migrants who arrived in Italy by sea.

Another worrying trend is the number of unaccompanied minors. In the first quarter of this year, the Tunisian authorities intercepted 110 minors, and 94 percent of them were unaccompanied. This compares with only 30 minors, of whom eight were unaccompanied, for all of last year. Much tighter restrictions for adults may be behind this rise, pushing poor families to encourage children to make the journey alone.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Enlargement : Illustration 4

The reasons why so many want to leave Tunisia are exactly the same as those that led to the uprising in 2011, according to the 2017 FTDES annual report. “It is the absence of a better future and of 'collective salvation' because of the deadlock in current political and social action which favours 'individual salvation' as the sole immediate solution for a suffocating Tunisian youth”, it says. “Tunisians partly flee from the unknown towards the unknown”, and many consider that their situation is now worse than before the revolution. And there are no changes on the horizon that could alter this.

In early January demonstrations were held in several towns against the lack of any economic and social improvement. They represented an outpouring against austerity and corruption, and the forces of law and order violently repressed them, arresting nearly a thousand people.

Nothing like this has been seen since the 2011 uprising, which sent hundreds of young people, those from deprived, marginalised regions who launched the revolution, towards the main exit routes for Sicily and Lampedusa.

FTDES's Bonnefoy pointed to an increase in the number of social movements in all regions, a rise in poverty levels, unemployment, a hesitation among politicians over addressing the growing social and political crisis, the absence of professionals and of any reassurances over the country's future. “The situation is not improving,” he said. “Inflation of the dinar is rising ever faster, which brings a loss of purchasing power for basic products.” Pressure from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) meant that VAT and other taxes were increased in the country's 2018 budget, he added.

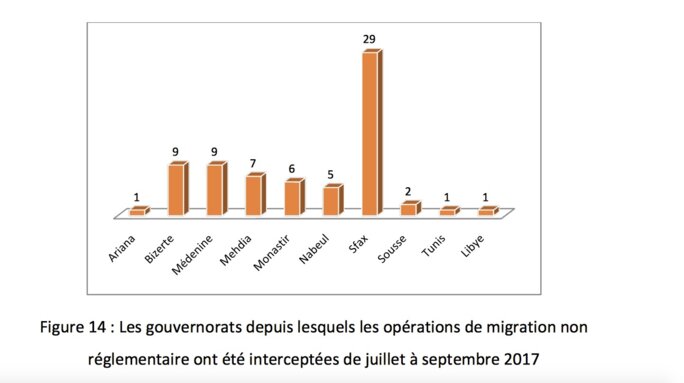

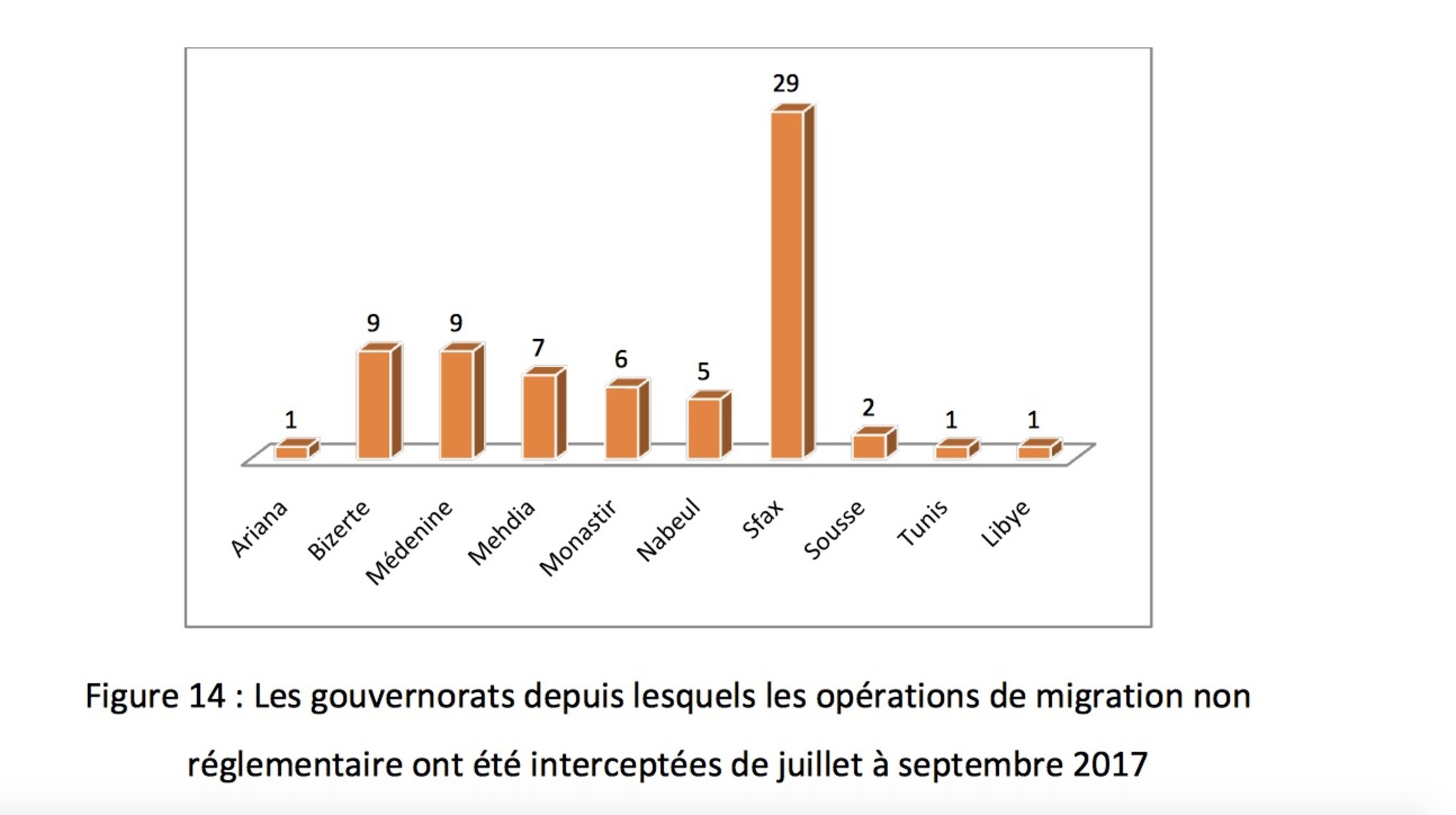

It was this context that a migrant tragedy hit the country on June 2nd. During the night a boat carrying 180 migrants sunk off Kerkennah, an island offshore from Sfax on Tunisia's eastern coast that serves as the main departure point for Sicily and Lampedusa – which is so full of people smugglers that it has become uncontrollable. The final death toll was put at 100.

Another accident had occurred some seven months earlier, in which 50 youngsters were killed when their trawler collided with a Tunisian marine patrol that was pursuing their boat, which had been carrying 90 people.

This latest tragedy has aggravated the political crisis which has been rocking the country for several months now. The fragile government coalition is split between the broad, secular Nidaa Tounès party founded by the country's president, and the Muslim democratic Ennahda movement. Four days after the shipwreck, interior minister Lotfi Brahem was fired, as were a dozen security chiefs for the Sfax-Kerkennah governorate. For it is the failure, or rather absence, of security policy in the region, plus the corruption of officers by people-trafficking networks, that explains why so many men, women and children lose their lives at sea.

Less than a year ahead of Tunisia's presidential election in 2019, and following the first municipal elections in May, the political situation remains very confused. The municipal elections reinforced Ennahda, but these polls were boycotted by massive numbers of young people.

Some say that Brahem was sacrificed by Youssef Chahed, the head of government, to save his own skin. Chahed, who came from the presidential party Nidaa Tounès but is now said to be supporting Ennahda, has recently been crossing swords with Hafedh Caïd Essebsi, the president's son, who heads his father's party. According to Jeune Afrique, 90-year old President Béji Caïd Essebsi will not stand in the presidential election, but he could postpone the poll for two years given the country's current instability.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Sue Landau