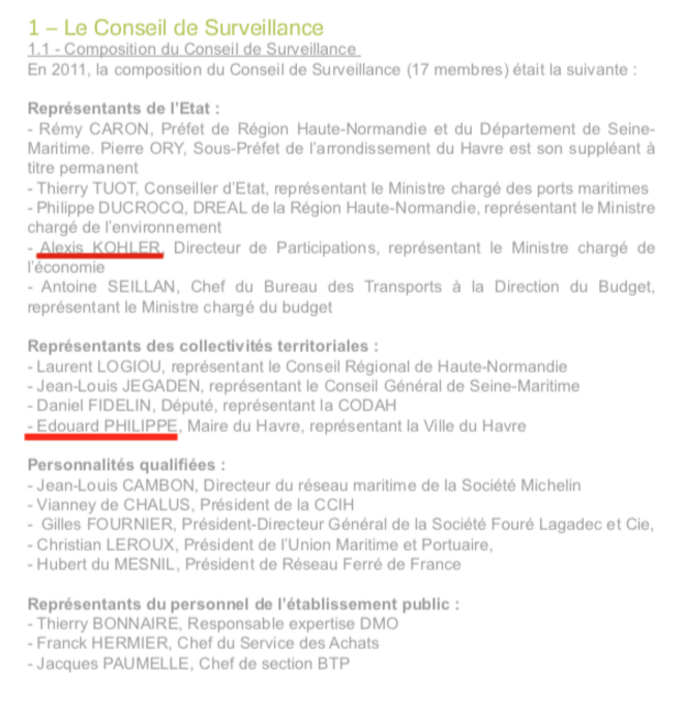

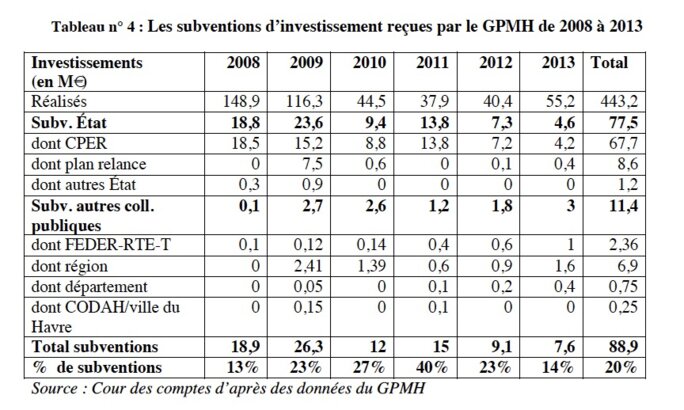

The issue clearly intrigued a member of France's ethics committee for public servants back in 2014. At the time Alexis Kohler, a senior civil servant who is now President Emmanuel Macron's chief of staff, was asking for permission from the civil service to join the massive maritime transport firm the Mediterranean Shipping Company (MSC). On the June 2014 declaration an anonymous hand has underlined the words 'Grand Port Maritime du Havre (GPMH)' - or Major Seaport of Le Havre as it is known in English - as if to attract attention to Kohler's silence on the issue.

For in their declarations Alexis Kohler and his immediate boss Rémy Rioux, who vouched for him, seem not to have enlarged on Kohler's role between 2010 and 2012 as an official representing the French state on Le Havre port's Supervisory Board. In 2014 the ethics committee ruled against against Kohler's private sector move to MSC, referring simply to his previous role as a state official on the board of the STX France shipyard. But at no time did it refer to his time on the Le Havre Supervisory Board. This is a port where MSC, the world's second-largest maritime transport company, plays a significant role not just as a client of the port but also as an important operator in its own right, as it controls two of its terminals.

The reason for this silence, this oversight, is doubtless contained in the documents now obtained by Mediapart. This website asked to see the minutes of the GPMH's Supervisory Board for the period that Alexis Kohler sat on it as a state official, having been sent there by the body that oversees the French state's investments, the Agence des Participations de l’État (APE).

These documents raise questions about the approach taken by Alexis Kohler, whose official title now is secretary general of the Élysée and who is facing a preliminary investigation by the financial crime branch of the French public prosecutor’s office, the PNF. They reveal that when he sat as a state official on Le Havre port's Supervisory Board, Kohler at no time informed the other members of the board of his family links to MSC. As Mediapart has revealed, Kohler's mother is a first cousin of Rafaela Aponte, co-founder and chief shareholder, along with her husband Gianluigi Aponte, of the maritime transport group.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Among the members of the board at the time was the then-mayor of Le Havre, Édouard Philippe, now Macron's prime minister, as shown in a list (see left) of members of the board in the annual report of 2011. Questioned about whether Alexis Kohler had informed the Supervisory Board about his family links to MSC, the prime minister told Mediapart that he has “known Alexis Kohler for a long time and has always admired his great integrity, his sense of civic duty and his strong work serving the general interest.” Édouard Philippe had already made the same comments in June when the prosecution authorities announced the opening of their preliminary investigation. As for the duties carried out by Alexis Kohler at Le Havre, the prime minister told Mediapart that he had “no comment to make specifically on his position on the Supervisory Board at the maritime port of Le Havre”.

But the minutes of the GPMH or Major Seaport of Le Havre Supervisory Board are quite clear. Kohler never stepped aside when an issue involving MSC was being considered by the board. He took part in all deliberations, including those concerning the Italian-Swiss shipping company. At least once he even voted for a measure involving public money that was favourable to MSC.

Alexis Kohler and the Élysée have, however, consistently denied any conflict of interest and have insisted that the public servant's family links with MSC were always fully disclosed as required by the law. “In all his successive positions in the state Mr Kohler has always informed his hierarchy, as well as those of his colleagues who needed to know, of his family links,” the Élysée said after the initial investigation by Mediapart. “These personal links were known to the Committee on Ethics in Public Service; Mr Kohler has never found himself in, or been placed in, a position as a decision maker or in a situation to assert a personal opinion on the internal workings and deliberations concerning MSC,” said the Élysée. “This remains the case for the present as it does for the future; Mr Kohler has always respected the decisions of the ethics committee.”

Today that first line of defence by the Élysée on behalf of Alexis Kohler looks to have been undermined. After the Benalla affair – which involves President Macron's personal bodyguard Alexandre Benalla beating up protestors – these new revelations will comes as a fresh blow to the presidency, amid allegations of conflicts of interest and failures to respect rules and the law.

STX France and the port of Le Havre - problematic posts

When he was promoted to assistant director of the state body the APE in 2010, taking over responsibility for the audiovisual and transport briefs from Rémy Rioux, Alexis Kohler must have been aware of the potential conflict of interest he faced over two cases – STX France and the GPMH or Major Seaport of Le Havre. In the first instance the French state was a shareholder, and in the second case the body involved was a publicly-owned body. Both involved public money. But both establishments were also important for MSC, which was looking for major financial support from the French state.

The fact that Alexis Kohler was handed a brief that included these two cases raises some key questions. Assuming they knew, as is claimed, why did his superiors give him a position that exposed him to such potential conflicts of interest? Did his superiors consider the risk of conflicts minimal and not worth changing the way the APE functioned? The answers are not clear at this stage.

On two occasions, in 2014 and 2016, Rémy Rioux, who was Kohler's boss first at the APE then as chief of staff to finance minister Pierre Moscovici, officially vouched for Alexis Kohler at the ethics committee when the latter wanted to join MSC. “I affirm that in the context of his work, Mr Kohler has never exercised any control or supervision, has not concluded any contracts with nor proposed any decisions relating to the operations carried out by the company MSC … which he wants to join, nor by its subsidiaries,” he wrote to the committee. In his statement Rémy Rioux was careful to refer only to the period when his colleague was his deputy in Pierre Moscovici's office but did not speak of the previous period when they were both at the APE.

As for Alexis Kohler himself, while he was eventually given the go ahead in 2016 to work for MSC, he had his own personal responsibility in the case. Why did he agree to sit on the board at STX France, which had become a very sensitive political subject, knowing that MSC was at the time virtually the only customer for the shipyards based at Saint-Nazaire in west France? And that at some point the question of state aid would arise? Subsequent events showed how favourable this aid was to MSC, as the state in effect played the role of its banker. The shipping company benefited from around 1.5 billion euros in financial guarantees signed by the state.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

MSC targeted Le Havre

The documents now obtained by Mediapart raise even more questions in relation to the Major Seaport of Le Havre (GPMH). How does one explain how Alexis Kohler sat on the port's Supervisory Board and even became a member of its audit committee, while knowing just how key the port was to MSC's plans to conquer the French market?

This was, moreover, a crucial period in the port's history. It was the time when the port authority privatised its terminals, and the roles of major players in the port were changing because of the reforms.

It was back in 2008 that the government of prime minister François Fillon under President Nicolas Sarkozy had imposed major changes on France's ports. The stated aim was to relaunch France's port industry which was languishing behind those of Belgium and Holland to the north and Spain and Italy in the south. New rules were written governing the way the French docks and ports ran, in particular on the organisation of dockers and the handling of goods at the port.

The ports now had greater autonomy, new rules of governance and new powers to boost development. The Supervisory Board was thus an important body, both for the maritime users of the port and for the economic and political life of the wider region. When Alexis Kohler joined the board he sat alongside the then-mayor of Le Havre, Édouard Philippe, the former mayor Antoine Rufenacht and the local state representative or prefect, and regional and departmental - county - councillors.

As a result of these reforms the old autonomous port of Le Havre (PAH) – now the Grand Port Maritime du Havre (GPMH), or Major Seaport of Le Havre – wanted a slice of the goods transport market that had been captured by Antwerp and Rotterdam. It had an ambitious strategic plan to develop an inter-modal link, allowing containers taken off boats to be taken by train to northern Europe.

In particular the port authority, backed by the state and all the local authorities, intended to create what is called Port 2000. This involved building new quays to triple Le Havre port's capacity and allowing the port to handle giant container ships. It wanted to become, for example, the leading hub for the import and export of new motor vehicles.

Encouraged by the huge state commitment to the development of the port, all the main maritime transport and storage companies wanted to get involved in the Port 2000 project and take part in the massive developments there, through signing terminal development conventions or CETs. Several gigantic terminals were built.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

MSC also wanted to take advantage of this situation. In partnership with regional firm Perrigault they already controlled two terminals – TNMSC and Seto – through its subsidiary Terminal Investment Limited. They wanted more.

At the time the Italian-Swiss group used tactics which had paid dividends in its conquest of Italy's ports; it increased the number of its commitments, gaining support and legitimacy from the authorities in return, even if the group had difficulty honouring its promises afterwards. It thus announced that it would bring invest around 160 million euros which would “allow MSC to receive any ship in its fleet on the same site, at any hour and whatever the tide”.

The port's annual report for 2011 quotes MSC France's Stephan Snijders. “We're delighted that the works have started with first delivery due at the beginning of 2012, while awaiting the delivery of other work at the end of 2012. The new installation will allow our largest ships to berth, with a guaranteed draught of 16 metres. That will certainly lead to an increase in activity and development for MSC at Le Havre,” Stephan Snijders said.

The port's annual report for 2011 (in French) can be downloaded here.A development funded with public money

But the truth was that it was above all the state and local authorities – in other words taxpayers – who had to put their hands in their pockets to fund this large project and attract the large shipping lines and storage and handling companies.

The public sector investment and financing organization the Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations was one of the bodies that contributed. The 2011 GPMH annual report said that it had signed a contract to borrow 150 million euros from the Caisse to ensure the “long term” development of the port.

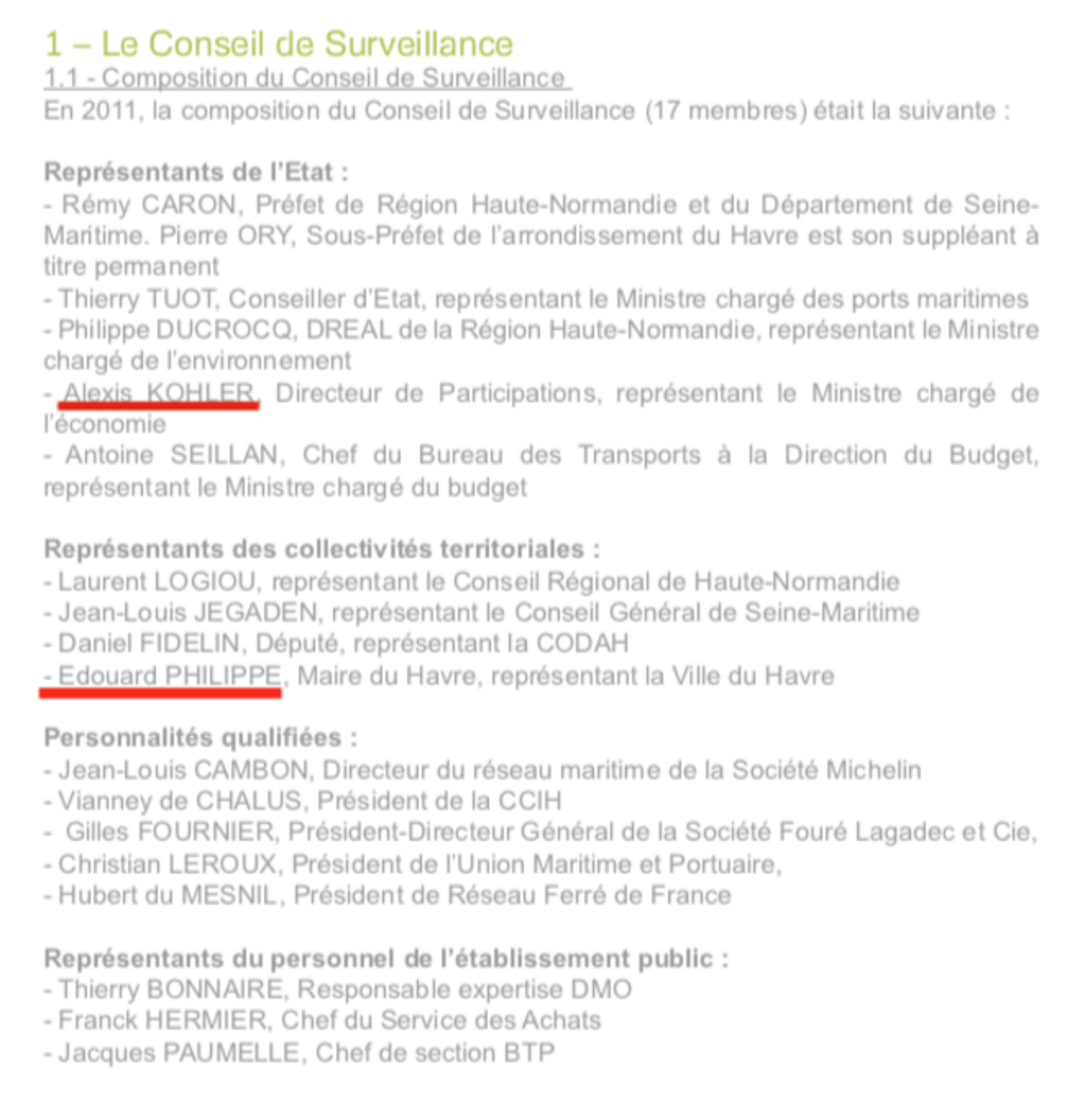

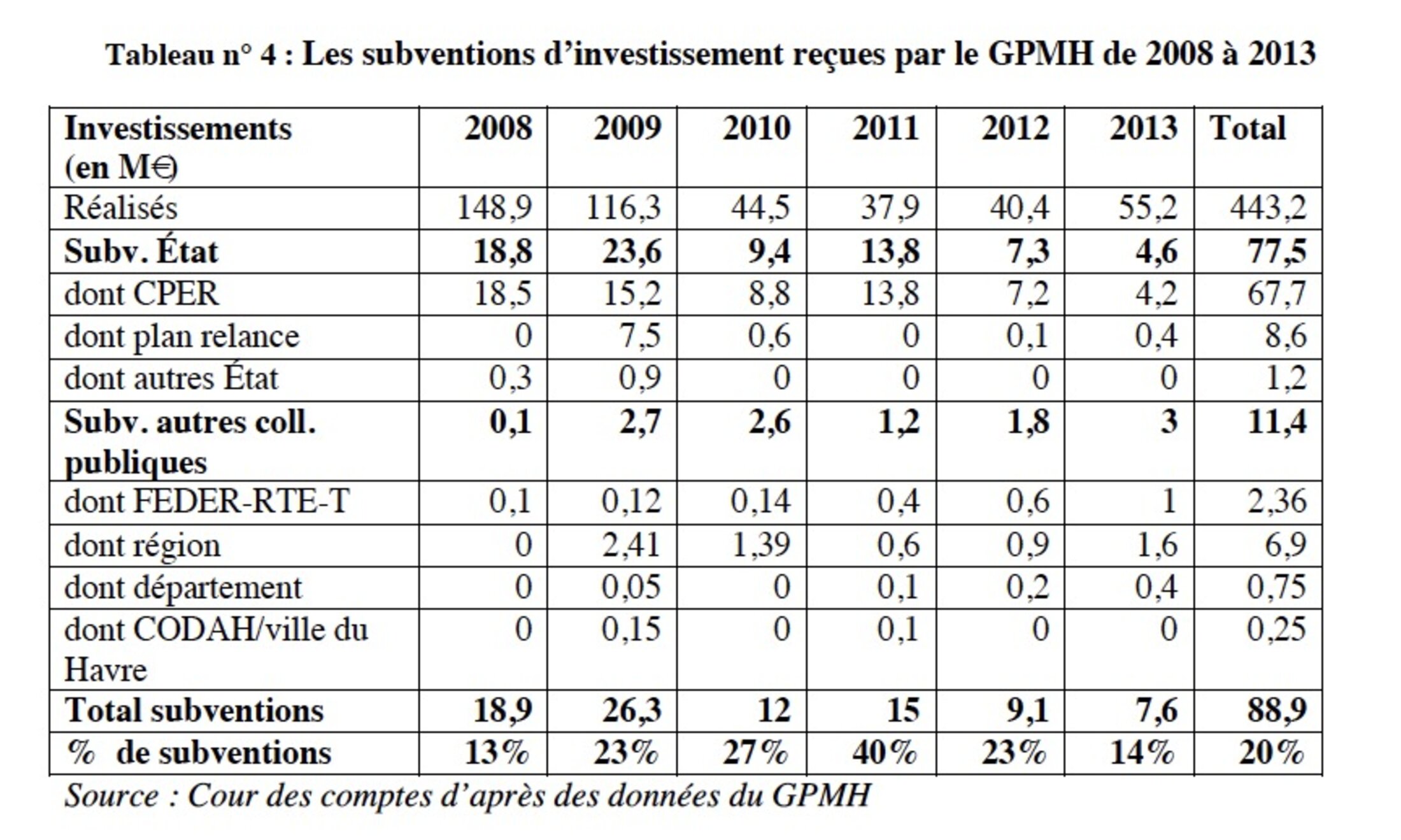

But public financial aid at the time went considerably further than that. In March 2016 the public finances watchdog the Cour des Comptes published a report on GPMH's financial performance from 2008 to 2013, which included the period Alexis Kohler was an administrator on the Supervisory Board. The report can be seen here.

The Cour des Comptes report shows that over the period 2008 to 2013 the port invested 443.2 million euros in its modernization and extension, including 302.2 million euros for the Port 2000 project. Part of the funding came from the port authority itself from its own reserves and through debt. But as the report shows a lot of the money came from the public purse; some 88.9 million euros or 20% of the total amount. Of this the bulk came from central government, comprising 77.5 million euros. Local authorities contributed 7.9 million euros or 1.8% of the total amount invested, with most of this – 6.9 million euros - coming from the Haute-Normandie region. European funds made up just 2.36 million euros or 0.5% of the overall spend, the report says.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

Declarations of interest

According to the minutes seen by Mediapart, the MSC group was often discussed by the Le Havre port's Supervisory Board. “We're in danger of seeing MSC's large ships leaving Le Havre all the time that TNMSC's works have not been carried out at Port 2000,” warns the board's director Laurent Castaing, who would later become president of the naval dockyards at Saint-Nazaire. “We shouldn't think that MSC can or must automatically come to Le Havre,” the director warns on another occasion, clearly aware of the needs of a major client. “MSC is very interested in Le Havre, all the more so as it has capacity problems at Antwerp,” he notes at a further gathering of the board. And he told another meeting: “TNMSC is ready to start the work. We must help them.”

Everyone on the board seems to have been unaware of Alexis Kohler's curious situation. Several elected representatives who sat on it at the time have told Mediapart they did not know of Alexis Kohler's family situation and that they were dumbfounded when they recently discovered his links to MSC.

Enlargement : Illustration 7

Yet as a result of the new rules of governance at Le Havre port, a new ethical procedure had been adopted by the Supervisory Board. Each member of the board had to fill in a declaration of interest, which included recording any family connections, Mediapart understands. Several members of the board clearly had trouble going along with this rule as the government commissioner in charge of overseeing the declarations of interest was obliged to issue a reminder. “It is not intended that the chairman of the board or the government commissioner systematically hunts out these potential situations and it is for each of the members concerned to take care to flag potentially contentious situations,” the commissioner stated during a meeting held on June 25th, 2010. He underlined that these measures were “justified so as to limit the risk of members of the Supervisory Board in relation to the the offence of having an unlawful conflict of interest”.

What did Alexis Kohler put in his declaration of interests? Mediapart sought this document from the Le Havre port, GPMH, who said that they were legally the responsibility of the government commissioner, who is currently Alexis Vuillemin. He is also also a senior official dealing with transport issues at the Ministry for the Ecological and Inclusive Transition. Alexis Vuillemnin told Mediapart by letter that he was unable to supply Alexis Kohler's declaration of interest. He explained: “Declarations of interest … are liable to include information relating to … the duties carried out by the declarant and their family in the 'companies or organisations' which are likely to conclude agreements with the Major Seaport.”

In other words, at the same time as prosecutors are seeking to establish whether, in the course of his duties as a public servant, Alexis Kohler helped MSC, his family's company, the government commissioner justifies a refusal to hand over his declaration of interest on the grounds that it would be a breach of his privacy.

Yet the rules to prevent conflicts of interest seem often to have been made use of on Le Havre port's Supervisory Board. On several occasions members of the board, including the mayor of Le Havre of the time, Édouard Philippe, absented themselves and abstained from voting, invoking the risk of a conflict of interest. Alexis Kohler never did.

Missed opportunities to absent himself

Yet during a period when new rules were being fixed for the mayor players in the port, there were several opportunities for Kohler to have stepped aside during discussions. On June 4th, 2010, the Supervisory Board met to discuss the funding that should be released on the work to build a multi-modal site at the port. This was a key issue for Le Havre, as it is for all ports. Port managers know that in order to compete they need to be able to extend their hinterland by using the railway and inland waterways to transfer goods from the sea, and not just the roads.

The minutes from the meeting on June 4th, 2010, can be read here (in French).

In its report the Cour des Comptes states: “The multi-modal site is the cornerstone of the industrial system of broadening the market, which includes improvements to the port rail network, the installation of railway loading equipment on the maritime terminals, shuttles allowing transfer between these maritime terminals and the multi-modal platform, as well as the improvement of access to Port 2000. It involved allowing the development of road and waterway mass transportation, by creating a site bringing together containers and swap bodies from the port zone terminals.”

At the June 4th, 2010, meeting the members of the Supervisory Board heard from the deputy director of operations at the port who explained the costs of the project. He put the total cost at 140 million euros, which was split between 42 million euros from the port, 27 millions from investments and grants of up to 70.4 million euros. “The state's share is 37.5 million euros,” he said.

The minutes noted that the mayor of Le Havre approved. “Mr Philippe remarked that the multi-modal site is a great project and that we can collectively be delighted with it.” Alexis Kohler said he backed the project. He said he was happy that the project “can move forward today, as its strategic interest for the port - once the economic and financial balance of the operation is indeed achieved - is clear and does not seem to be opposed by anyone”.

And he voted for it. As the state's representative on the board that was a natural thing to do. But did he just do it as a representative of the state? Was he completely unaware of the great ambitions that MSC harboured in such developments? At that time the MSC group had also started to become involved in the port of Trieste by taking control of the quays but it also wanted to project manage a multi-modal scheme at that port to transport goods to Vienna and beyond.

On September 24th, 2010, the port's director Laurent Castaing explained that two warehousing and handling companies, including TNMSC, were asking the port to buy some equipment and tools that they were going to leave behind on some quays following their move to the new Port 2000.

Read here the minutes of the Supervisory Board meeting on September 24th, 2010 (in French).

To justify this unusual procedure, the port director referred to the financial crisis at the time and said that the two companies concerned were currently negotiating with their banks, who were looking for collateral against investments of between 50 million and 100 million euros. Castaing said that the companies noted that in the agreements relating to Port 2000 it allowed for the possibility that once the existing agreements were completed the port could buy the infrastructure part of the old terminals. “These companies are asking that we don't wait for the end of the terminal agreements to state our wish to buy, but that we do so straight away,” said the director.

'A company whose shareholders have an unknown or variable reliability'

Laurent Castaing admitted that when the plans for Port 2000 had been drawn up, this had not been the port's approach and that the “operators' investments had to be made at their own risk and peril”. But there was now a financial crisis and a difficult economic situation. He proposed that the port did indeed promise to buy the infrastructure, but not for the whole terminal “as it's important that the operators keep some of the real risk on the terminals”. This proposal was a way of “establishing” the companies in Le Havre, said Laurent Castaing, who said the purchase would be at “80% of the unamortised value”.

Enlargement : Illustration 8

Alexis Kohler then took part in the ensuing discussion, supporting the proposition while at the same time suggesting that it could pose a problem. “Mr Kohler went along entirely with the approach of conducting this negotiation in two steps. He realised that in this case, in particular for reasons linked to the current economic situation, the port had been led to play the role of banker for these operators, in any case intervening financially, even though it should not do so. They had to consider the port's interests but also the possible ripple effect on the other operators,” he is quoted as saying in the minutes. Despite these cautious comments, Kohler voted for the director's proposal.

What did Alexis Kohler mean when he said that the port was right to intervene financially “even though it should not do so”? Did he already know that a financial intervention of this kind by the port in favour of the operators, including MSC, overstepped the rules?

In its report on the port of Le Havre the Cours des Comptes is quite clear that the port should never have approved such a purchase. It cited France's general code governing property owned by public bodies (CGPPP) and said that under this code the property involved in such agreements should become the French state's property for free. The financial watchdog was quite clear that even if there were measures in the terminal agreements that allowed the port to buy part of the infrastructure from the operators, these were not enforceable in as far as they were contrary to existing law.

Thus the state's representative on the port's Supervisory Board, Alexis Kohler, gave his backing for a measure that led the Le Havre port effectively to operate as a bank. The port agreed to provide a guarantee of purchase from the two operators, one of whom was TNMSC, even though the Cour des Comptes says the property should have become “freely and fully the property of the state”.

Not only did Alexis Kohler not absent himself from a case that directly concerned MSC, he also gave the state's support for a measure which was illegal and against the public interest. And all that was done to the great benefit of the Italian-Swiss shipping company, without the board questioning it for a moment. For it is curious that an operator complains of being in financial difficulty to the people it is dealing with and then at the same time promises to invest hundreds of millions of euros in Le Havre.

TNMSC was often the subject of discussions on the Supervisory Board. For example, on September 30th, 2011, the board discussed the company's move from Quai Bougainville at Le Havre port to the new Port 2000.

Read the minutes of the Supervisory Board's meeting on September 30th, 2011, here.

At this meeting the board was called on to make an urgent decision, with members finding out about the issue virtually when they got to the meeting itself, and they did not have time to study the matter in depth. Laurent Castaing opened the debate, pointing out that the plan was of considerable importance for MSC. He reminded members that MSC - “the second biggest shipping line in the world” - had been interested in moving to Port 2000 from the day that the idea for it was mooted. “Today, in the view of MSC and TNMSC, the time has come to move to Port 2000,” he explained.

The question was the circumstances in which the move should take place and above all how many positions TNMSC should occupy at the new port. The original agreement was for three, but TNMSC wanted four. Even if TNMSC did not yet fulfil all the conditions to take over their positions, should an exception be made for them? At the time the development of Port 2000 was being handicapped by a quarrel between two different cargo handlers and one of him – MSC's partner company in TNMSC – was refusing to budge despite the undertakings it had given.

Alexis Kohler was involved in the discussion. He first referred back to the purchase of the company's goods after the end of the terminal agreement, which accompanied the move, and confirmed that he had not known that the measure adopted some months before was illegal. “I'm still a little uneasy with the question of the fate of the property at the end of the agreement,” he told the meeting. “The port is finding itself in the role of banker which, naturally, it should not be doing. That's a bit concerning.”

However, it is his following remarks that are surprising, as Alexis Kohler behaves as if he did not know MSC, and insists on the need to obtain strong guarantees from the group. “The first very positive point relating to the way we regarded the case in September 2010: this time the guarantee is priced. A range is being offered us and this guarantee will be at the high end of the range,” he said.

Speaking of TNMSC, which is 50% owned by MSC, he added: “This is predicated on there being an idea of the financial reliability of the operator in question. This is not the place to debate it but I insist on the need to be extremely vigilant and to be very clear on the fact that there should be the most objective analysis possible knowing that we are dealing with a company whose shareholders have an unknown or variable reliability.”

It is true that it might be harder to find a better way of describing MSC as a company whose shareholders have an “unknown or variable reliability”, given that a certain opaqueness surrounds the group whose controlling interests are in a trust based in Guernsey. But for Alexis Kohler to speak like that as if he knew nothing at all of the group controlled by his family is curious.

Competitive advantage

Having distanced himself in this way, Alexis Kohler then went on to support the measure that was going to benefit MSC. “What strengthens or reinforces the proposal that has been made to us is the fact that we have a commitment of volume,” he said. The board was open to this argument. And despite the reservations of the government commissioner the board voted without hesitation for the proposal that had been put before them by management as a matter of urgency. Alexis Kohler was among those who voted for it.

Thanks to this vote TNMSC were given four positions at the new Port 2000 as they had wanted. After a supplementary urgent vote, it was agreed that the cost of the use of the land would be based on 2006 indicators. There was also an agreement to buy the company's old facilities. MSC was the only company to get quays with depths of 17 metres, compared with 15 metres for the others. This gave it an advantage over its competitors. However, the commitment made by the shipping company about the volumes of trade it would handle at the port seems to have been hard to meet. The Cour des Comptes said in its report that “in relation to the traffic, the strategic plan was too optimistic”.

Enlargement : Illustration 9

From that time on, MSC's position at Le Havre was secured. Though he remained the state's representative on the Supervisory Board until June 2012, Alexis Kohler did not attend another meeting. He handed his voting rights to other representatives. At the same time the composition of the board changed. In February 2012 Laurent Castaing, who had been the director of Le Havre port, was named president of shipbuilders STX France. In its report the Cour des Comptes welcomed the change in management at Le Havre. It underlined that having taken numerous risks “one can nonetheless see a change in the handling of the dossier in the sense of a greater firmness in relation to the operators with the arrival in 2012 of the current director general”.

The forgotten ethical rules

A reading of these different documents leaves little doubt about Alexis Kohler's approach on the port's Supervisory Board. Contrary to what he has maintained, in this case he never absented himself when there were discussions involving the MSC shipping company or its subsidiaries. He took part in discussions and he voted, even approving decisions that proved to be problematic.

Given all this, how can one believe that he was able to show exemplary behaviour and respect for the laws and ethical rules in his subsequent positions? He was the state's representative on the board of directors of the shipyards in Saint-Nazaire, then deputy chief of staff for the minister of finance Pierre Moscovici and then chief of staff to Emmanuel Macron when the latter was minister for the economy. Can one believe that he stepped aside each time that an issue involving MSC was discussed? His approach at Le Havre – and subsequently, too, when in March 2017 he visited his old employers at the Economy and Finance Ministry in Paris in his then role as finance director for MSC, to defend the company's interests in issues concerning the Saint-Nazaire shipyard – suggest that he is scarcely discomforted by rules concerning conflicts of interest.

But Alexis Kohler's behaviour raises other questions too. In particular it raises questions about those who officially vouched for him. Rémy Rioux – who took on this task rather their minister, Pierre Moscovici – told the ethics committee that Alexis Kohler had never been in a position where he had given his opinion on a contract with MSC. He could not have been unaware of his colleague's role at Le Havre – Kohler replaced Rioux in that job - and the issues that were discussed by the port's Supervisory Board. But Rémy Rioux did not make any mention of the issue.

Enlargement : Illustration 10

There is also a question over the statement made by Emmanuel Macron in 2016 to the ethics committee when he was minister for the economy. Either Macron was taken advantage of by the man who would become his closest aide as president; or he knowingly provided a statement that did not conform to the facts. Two hypotheses, but which one is the right one? The government's response to the Cour des Comptes's 2016 report on Le Havre, which was co-signed by the minister of finance Michel Sapin and the minister for the economy Emmanuel Macron, at least clears one question up. Macron must have aware of the favours given to MSC by the state-owned port when his senior aide was a member of its Supervisory Board.

Finally, a new character has emerged in the saga: Édouard Philippe. Without doubt the prime minister did not know of Alexis Kohler's family links with MSC when he sat on the port's Supervisory Board in his capacity as mayor of Le Havre. But he could no longer be unaware of them after Mediapart's revelations and the opening of a preliminary prosecution investigation into the case. Some detailed memories of the port's Supervisory Board meetings may have come back to him. So why did he allow the Élysée to make such a full denial, if he knew the reality of events? Was it because this was a case that involved the Élysée?

These new facts now lead to a serious question: in view of the apparent mixing of private interests and public responsibilities, can the secretary general of the Élysée be kept in his position at the very top of the French Republic?

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

English version by Michael Streeter