Following the end of the Second World War, a revolution in agricultural practices came about in Europe with the arrival of intensive farming, boosting production volumes to feed under-nourished populations. Its development through subsequent decades saw an expansion in the surface sizes of farms, ever more performant machinery, and the massive use of chemical-based phytosanitary products to ensure high yields.

The credo behind it, and which has justified the same practices in development policies around the world, is the need to feed the planet. But the claim that intensive agricultural practices are the only solution has become increasingly challenged, notably through an awakening to the dangers of the chemical phytosanitary products poured over and into the land.

A growing body of research suggests that an agricultural model that uses no chemicals, one that is respectful of the environment and wildlife, can also feed populations on a large scale, and notably organic farming, until now so often limited to small holdings and short supply chains.

This year in France has seen a number of publications, including scientific studies and essays, which reinforce the idea that it is possible to meet the food supply demands at a European-wide level by replacing conventional agriculture with what are called agroecological methods of farming.

Agroecology includes the principles of organic farming, but also embraces broader societal, environmental and economic considerations for its sustainable application. It involves placing ecology at the heart of agricultural activity, as opposed to solely production objectives.

Its social approach includes “re-establishing the links between the farming community and those who consume food, based on values of equity, justice, participation and democracy”, writes Canadian agronomist Alain Olivier in a book published earlier this year in France entitled La Révolution agroécologique. Nourrir tous les humains sans détruire la planète, (“The agroecological revolution: Feeding all humans without destroying the planet”).

A lecturer with the sciences of agriculture and food faculty at Laval University in Quebec, Olivier is a keen proponent for the adoption of such a system on a global basis. He underlines that agroecology, far from being a 21st-century invention, “appears to be probably as old as agriculture itself”. He writes: “An attentive analysis of traditional agricultural production systems, notably in various countries in the global South, has allowed to shine a light on the knowledge and numerous skills of farmers which indicate a fine understanding of natural balances, and a management of agricultural plots closely tied to the maintaining of such balances.”

Under this umbrella of ecological practices is agroforestry, which is essentially the growing of trees around or among crops, and which, among other benefits, captures carbon that lies within the soil and contributes to efforts to reduce climate change. “In fact, agroecological practices constitute one of the rare tools that permit to both diminish climate changes and to adapt to them,” writes Olivier.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

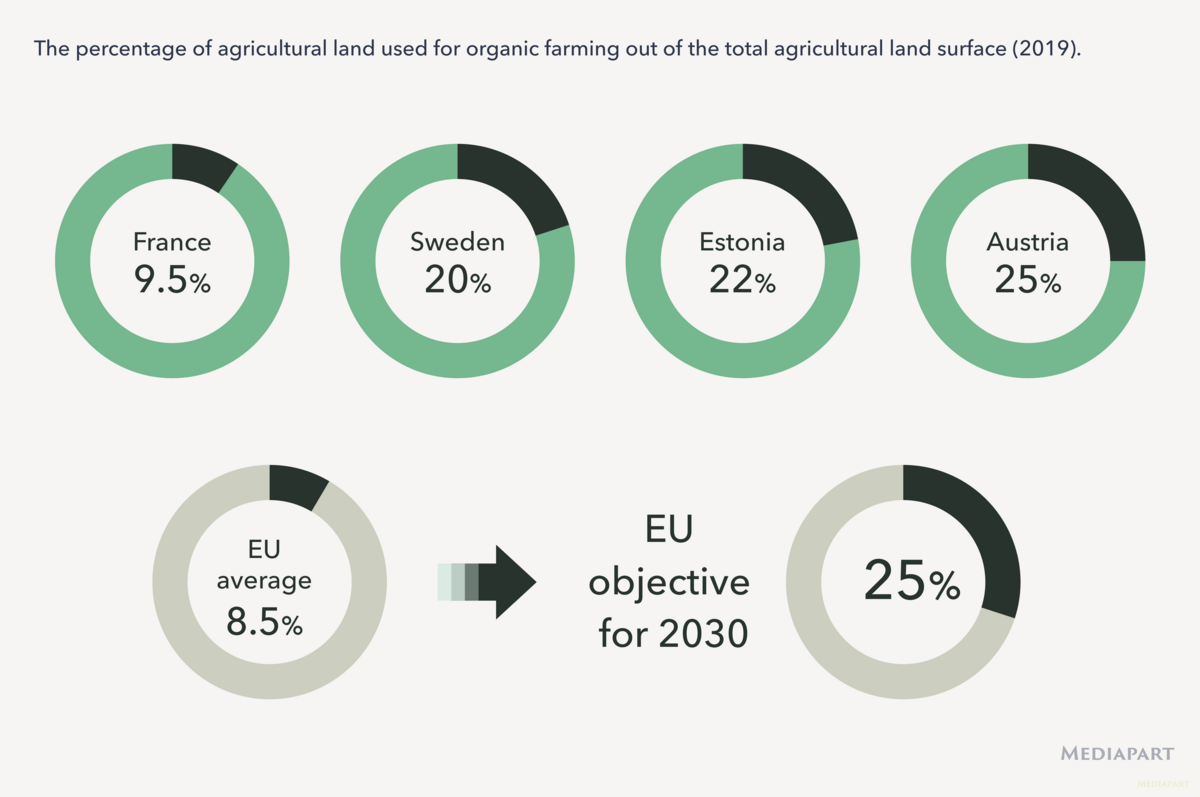

Today, organic farming represents just 8.5% of all agricultural land in Europe, while the European Commission has fixed a target of raising that to 25% by 2030.

But could the continent reach a level of 100% of agricultural land turned over to organic principles of farming, and if so, what would be the nature of the transformations and political choices required to reach that goal?

French agricultural engineers Xavier Poux and Pierre-Marie Aubert attempt to provide answers to those questions in their co-authored book, published this month in France, entitled Demain, une Europe agroécologique (“Tomorrow, an agroecological Europe”). It leads on from their research for French think-tank IDDRI, which promotes policies for sustainable development, and for which Poux and Aubert published a study in 2018 called Ten Years for Agroecology in Europe (TYFA). That defined a realistic roadmap for a Europe-wide transition to agroecological farming by 2050. They calculate that agroecological farming methods could feed what they forecast will be a total population of 530 million among EU countries by the year 2050.

Their model, in their own words, is “not only desirable, but above all perfectly conceivable on a Europe-wide scale”, but on condition that food production changed “towards more sustainability and, let it be said, moderation” – for doing away with synthetic pesticides and fertilizers can be expected to lead to a fall in the volume of production.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

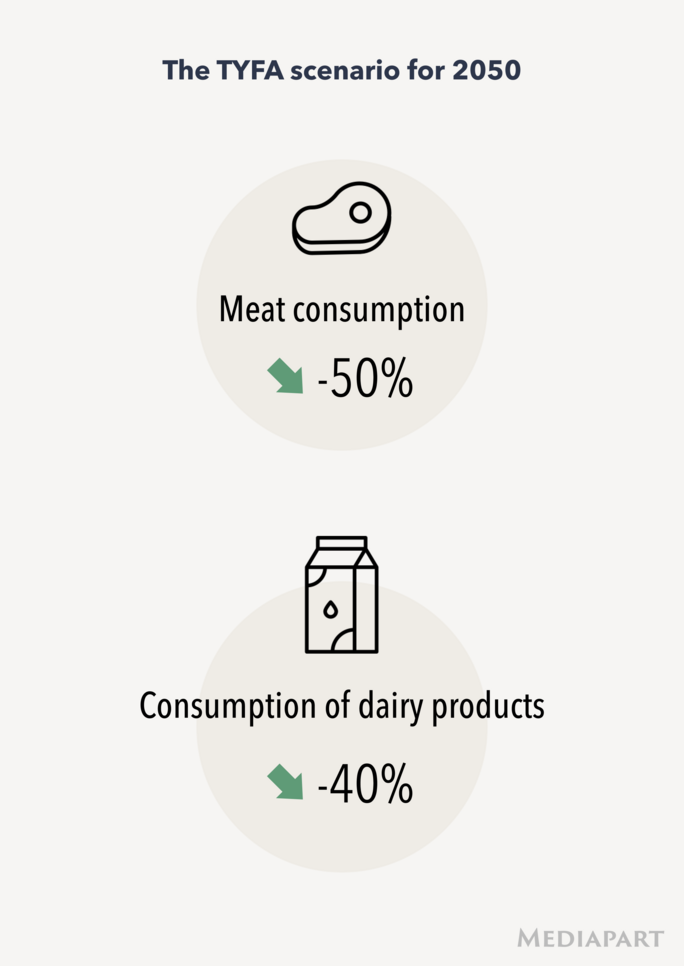

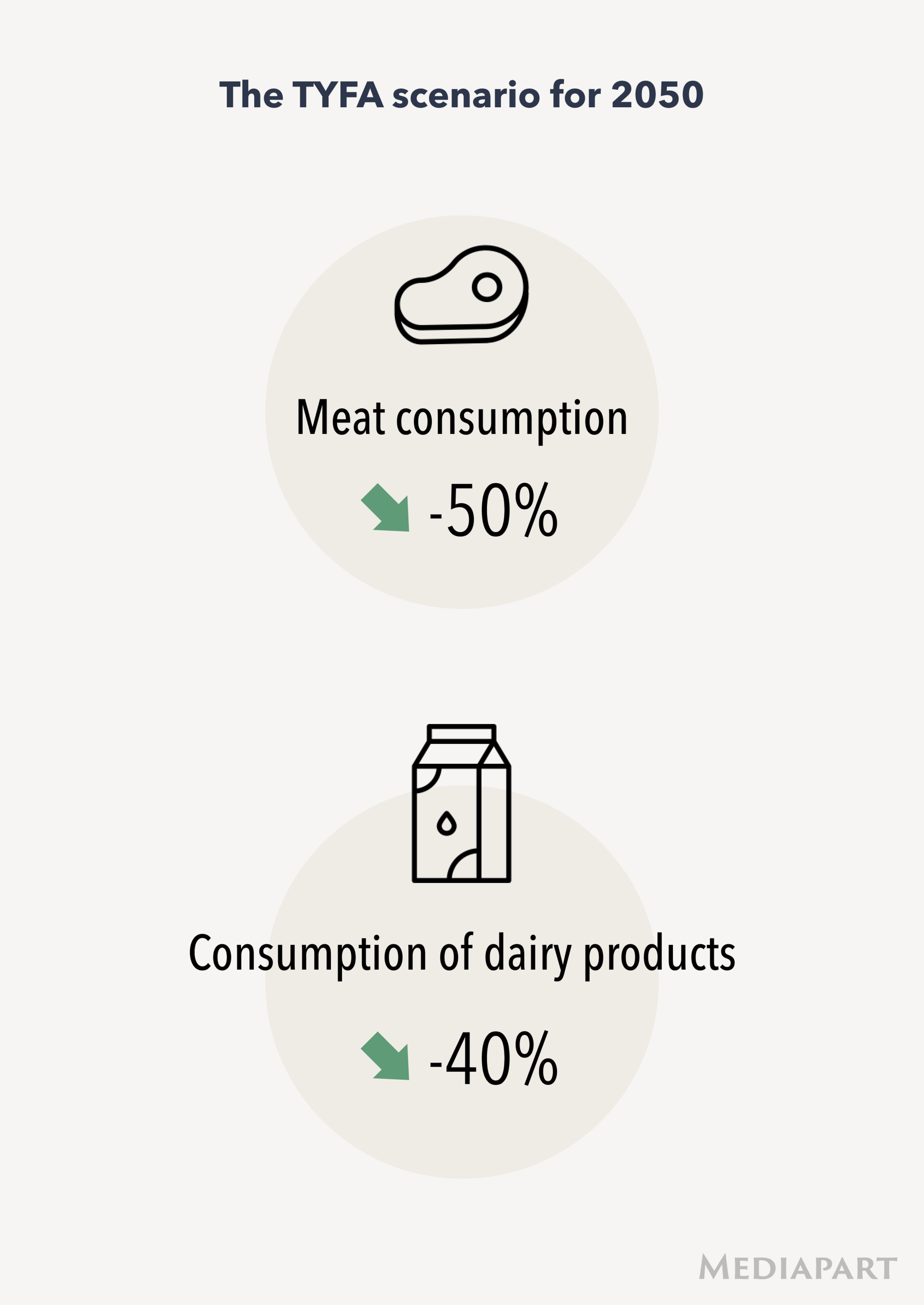

To accommodate that without increasing the size of farmed land, they argue for a drastic, 45% reduction in the volume of meat production (and within that amount a 70% reduction in volumes of poultry and pigs), which in turn would reduce the cultivation, and also imports, of cereals.

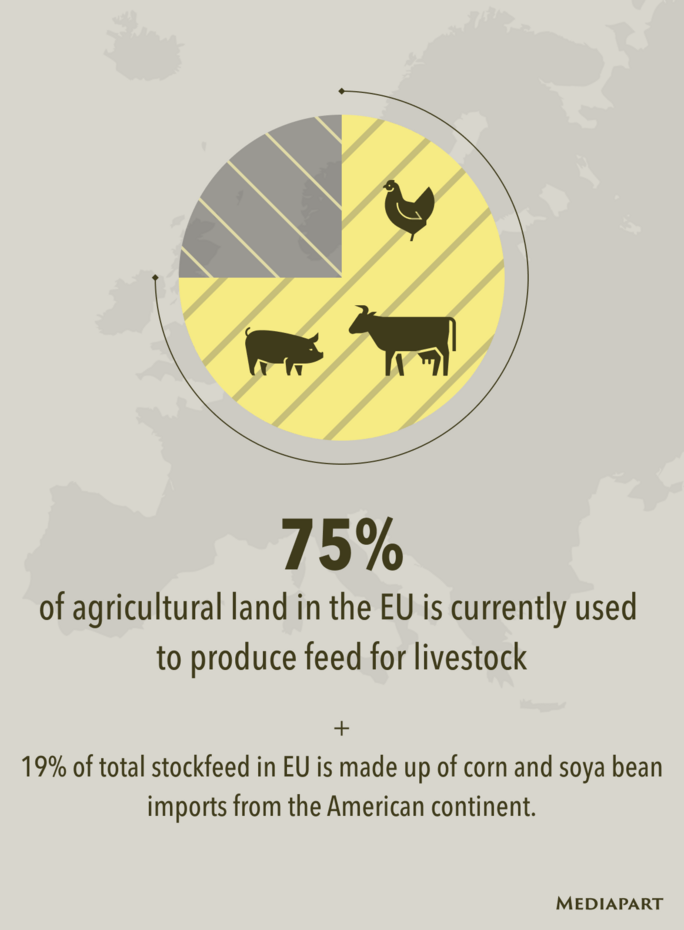

They calculate that this would represent a fall of 30% in cereal cultivation compared with that in 2010 (the year the researchers chose for their data comparisons when preparing their TYFA report), and lead to a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions produced from meat-production activity by 36% (in comparison to 2010 levels). Around three-quarters of farmed land in the EU is dedicated to producing livestock feed.

The aim here is to phase out industrial animal rearing, and instead turn to the development of free-range methods, with pastures that help balance ecosystems and maintain landscapes, for example with their hedges, trees and ponds, and the manure and compost that nourishes the soil in place of industrial, nitrogen-based fertilizers.

A greater use of leguminous plants (like clover, alfalfa and sainfoin) in crop rotations would provide a natural source of nitrogen, an essential nutrient for plant growth, which they embed into the soil from the air. The advantage here is that while these plants can provide animal feed, they are also a source of proteins for humans, and a base ingredient for 'green' fertilizers.

Poux and Aubert underline that the agricultural transformations which they propose would require a seachange in European food consumption habits – less meat and less dairy products, and more vegetable-based protein. The TYFA model projects a reduction of 40% (compared to 2010) in the volume of dairy food consumption, and a 50% cut in meat consumption. Already in France, a trend towards this has begun; according to research by the CRÉDOC, a semi-public association that monitors French consumer habits, the consumption of meat fell by 12% between 2007 and 2016.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

The two agronomists propose a shakeup of farm organisation, replacing the concentrated activities of conventional agriculture with a return to diversified activities – polyculture – by which animal rearing is complimentary to crop growing, and vice versa. As part of this, regions also should have more diversified agriculture, as opposed to the current situation in which, for example, farming in Brittany in north-west France is largely dedicated to animal rearing, while the Beauce region, to the south and west of Paris, is turned over to intensive cereal production. Agroecology does away with the conventional agricultural practice of cultivating vast fields of a limited variety of crops, and instead widens cultivation to a far more diverse mix.

While Poux and Aubert do not argue for strictly local food supply chains, which are inappropriate in a programme to meet Europe-wide demand, they see advantages for certain short supply chains in that they reduce carbon emissions and can limit eventual disturbances to longer supply chains.

The model proposed by Poux and Aubert is one of radical change but, they write: “History suggests to us that it is entirely possible. Farmers were able to lead an agrochemical revolution between 1950 and 1980; what TYFA proposes is an agroecological revolution between now and 2050.”

That “revolution”, however, does not demand only a conversion of farming methods and a change in food consumption habits. It also requires the end of investment in intensive animal farming, a reduction in slaughter houses, a restructuring of the large retail chains and a massive supply of organic agricultural produce, all of which cannot come about without political willpower.

That is a message present between the lines of a scientific paper published by the review One Earth in June, co-authored by a team of nine European academic researchers, led by two affiliated to France’s national centre for scientific research, the CNRS. Like Poux and Aubert, they set out a model for the Europe-wide adoption of agroecology by 2050, and included the same broad propositions; a reduction in livestock numbers, an end to imports of animal feed, an evolution of consumers’ dietary habits, reconnecting livestock and crop-growing to allow greater use of natural manure, and the introduction of leguminous plants to crop rotations to do away with synthetic nitrogen-based fertilizers.

The study, directed by French biochemist Gilles Billen, above all details a model to counter nitrogen losses in order to reduce greenhouse gases and the pollution of ecosystems. But it also includes a novel proposition – the recycling of human excrement for agriculture. The researchers estimate that 70% of the excrement of what they forecast will be a total European population of 600 million by 2050 (more than the prediction of Poux and Aubert) could be used to fertilize agricultural land in place of synthetic fertilizers. That would require, they note, the lifting of the current EU ban on the use of human excrement in organic farming on the continent.

As with the TYFA model, theirs allows for no expansion of the current agricultural land surface, despite the growth in populations, and proposes to end imports of products that are linked to massive deforestation and greenhouse gas emissions (19% of current European livestock feed is made up of corn and soya imported from the US and South American countries).

They further argue that the size of animal farms should be reduced so that the livestock can be fed from local production. As a yardstick, and because other comparative data is unavailable, they cite the levels of the 1960s, when the number of animals reared in Europe was almost twice as less than today. The researchers calculate that at a European level in 2050, their model would provide for the equivalent of an average 0.37 dairy cows per hectare of dairy farmland, as opposed to 0.68 today, and an annual surplus of 30 kilos of nitrogen per hectare of agricultural soil, compared with 63 kilos today. Animal and crop farms would be brought closer together to favour local exchanges (such as manure and animal feed) in a scenario resembling bygone agricultural practices (but employing modern scientific knowledge and machines).

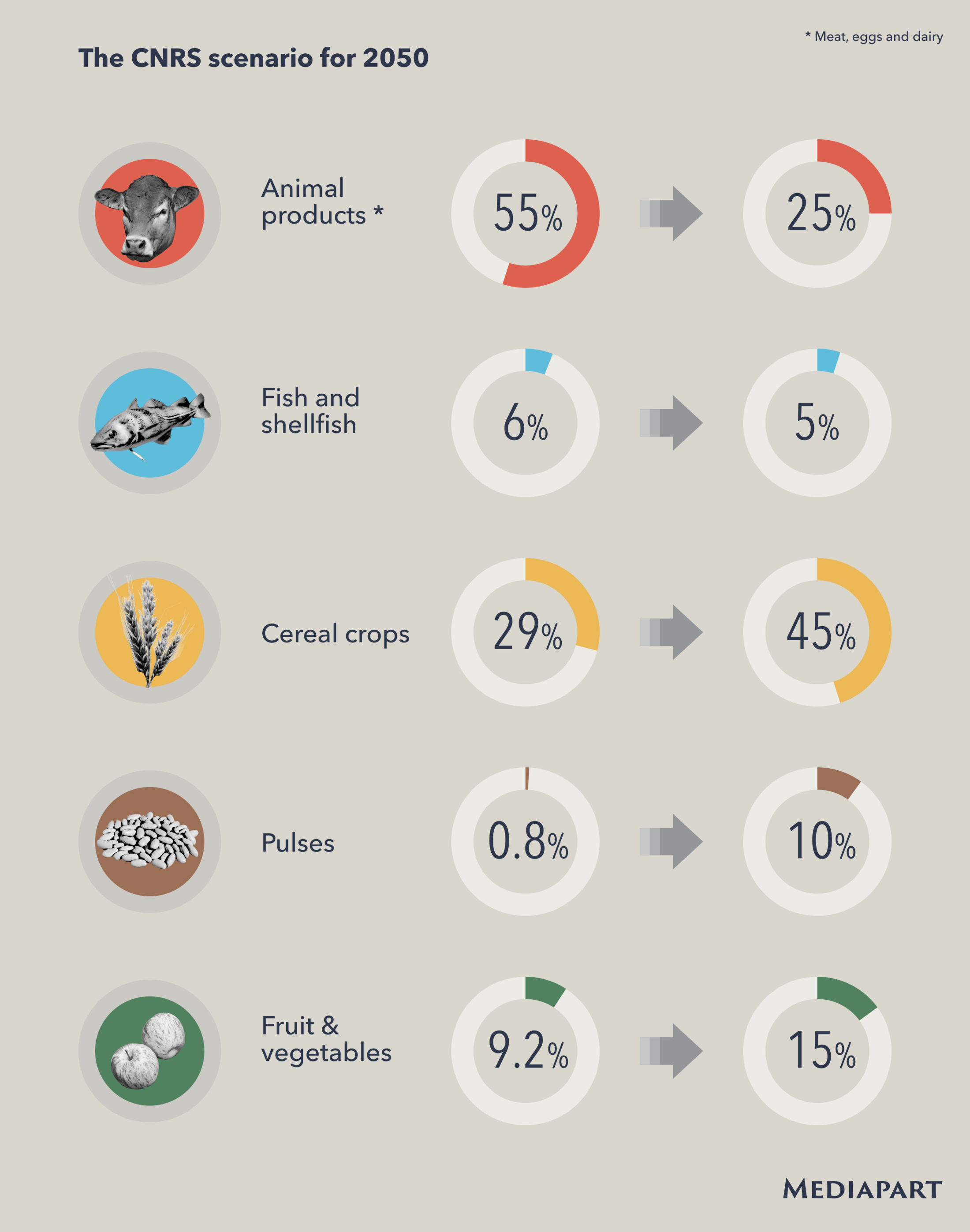

As for dietary changes, they propose limiting all food of animal origin (meat, eggs, cheese and milk, and other dairy products) to just 25% of food consumption. Over the period 2009-2013, average European diets included 55% of food of animal origin.

Meanwhile, the EAT-Lancet commission of international scientific advisors, cited in the paper published by One Earth, advises a healthy diet could be composed of just 33% of ingredients of animal origin.

The CNRS-led researchers also propose in their model (see illustration below) that the proportion of cereals in diets in 2050 could be 45% (this compares with a European average of 29% over the period 2009-2013), with 10% of pulses (2009-2013 average was 0.8%), 15% of fruit and vegetables (compared with a 2009-2013 average of 9.2%) and 5% of fish and shellfish (compared with an average 6% over the period 2009-2013).

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Other models, also based on the horizon of 2050, are discussed in a book published in France earlier this year entitled Un monde sans faim (“A world without hunger”), co-authored by Bordeaux university associate professor in sociology Delphine Thivet and sociology researcher Antoine Bernard de Raymond, who works for the French National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food and Environment (INRAE).

One of the models, which all argue for a reduction of animal proteins in dietary habits, results from a study called Agrimonde-Terra, a research project coordinated by INRAE and French agricultural research organisation CIRAD which attempts to address the inequalities in attaining food security around the world, and to do so without relying on an increase in production. This involves changes in the use of agricultural land that do not involve its expansion, and is guided by a nutritional approach (essentially more fruit and vegetables, and less meat) according to different public health requirements, and a regional organisation of food supplies.

But such changes to the food supply system in place are resisted in many quarters, as Thivet and Bernard de Raymond highlight. Food security remains dominated by the high-productivity and free market paradigm championed, in various forms, by international organisations like the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) or the World Trade Organization. The productivist approach counts on new technologies in order to increase yield around the planet, and adaptation to new conditions caused by climate change, the effects of which are already very real, and promoting the use of genetic engineering.

“Given that it is also these institutions which, in large measure, attribute the greatest funding to states, they contribute to maintaining a simplistic view of the problem of food security, coupled to the necessity of increasing agricultural investments,” write Thivet and Bernard de Raymond.

Support for agroecology, while still a minority camp, has been growing over the past 15 years. As noted by Un monde sans faim, it is a concept that has been increasingly championed by militant small farmers’ movements around the world who call for local populations to determine their food supply policies. “These are social groups directly affected by hunger and who want to express and assert their demands,” write the authors. That was illustrated in the boycott by a number of African farmers' associations of last month’s United Nations Food Systems Summit, and who denounced the increasing sway of industrial agriculture on their continent.

In his book La Révolution agroécologique, Canadian agronomist Alain Olivier points out that most people suffering from hunger around the globe live in rural areas. Some of them work in agricultural activities, but without access to land ownership. “Very often, industrial agriculture does not, or only very little, serve to nourish the population of the area where it is based,” he writes. “It targets an export market which, furthermore, is not always intended for feeding humans, but rather other uses, notably industrial, also.”

Enlargement : Illustration 5

The book by Olivier and those others cited here all have the merit of unsettling the conventional wisdom that only agriculture that depends on the use of chemicals, with its resulting high yields, can feed the world. Olivier demonstrates that, on the contrary, such methods have failed to do so. Every continent is affected by under-nourishment (including 821 million people in Africa, according to data from the FAO), and the problem has been aggravated by the economic and financial crises which began in 2008 – and which was then a record year in the volume of worldwide agricultural production. The challenge of feeding what will be a global population of 9 billion in 2050 will not, to all evidence, be met by productivity-driven agricultural systems.

In a paper published in June this year in the scientific review Global Food Security, a team of French and US researchers assessed the claim that agroecology could improve food security and nutrition. They sifted through 11,700 studies on the subject that were published between 1998 and 2019. Out of those, the researchers selected 56 scientific articles that met a set of strict scientific criteria they had established. Their conclusion was that 78% of all those studies convincingly demonstrated that that agroecological practices improved food security and nutrition, notably among populations of low-income countries.

In France, public agricultural research institute INRAE, which previously favoured conventional intensive farming, is now increasingly studying experiments in alternative practices. In February 2020, it announced the launch of a Europe-wide research programme, with 23 other agriculture research bodies on the continent, to study what it called “the ambitious vision of an agriculture free of chemical pesticides”.

“A strong demand from public authorities, agriculture professionals, and society in general, all over Europe, has spurred collaborative research in order to accelerate the agroecological transition,” it said in its presentation of the programme, the aim of which is “to build a scientific roadmap that will soon be presented to the European Commission, as a contribution to the European Green Deal”.

Last month, the institution also announced (in French, here ) a vast inter-disciplinary programme bringing together various research projects on the issue of increasing the scale of organic agriculture, in line with EU targets and even more ambitious goals, and public demand. The programme, the INRAE explained, would “explore the hypothesis whereby the national offer of organic produce will become the largest [among agricultural production]”, and noted that, “A world agriculture that would be converted to organic [farming] in the medium term to 50%, or even more, would necessitate a radical change of the whole agri-food chain”.

Among the experimental research projects undertaken by the INRAE is the development of an insecticide based on essential oils extracted from clove plants, orange peel and spearmint. Others include research into organic pig rearing systems, the adaptation of cooperative centres to the growing scale of organic production in the Occitania region of south-west France, and the evaluation of manure and nitrogen requirements to nourish the expansion of organic farmland.

Some of the conclusions of that research echo the studies cited further above. One is that an increase in the cultivation of leguminous plants, together with the relocation of ruminant animals alongside crops, can provide the nitrogen needed for an expansion of organic farmland.

In its presentation of its activities and projects involving organic farming, the INRAE concluded: “Far from the hyper-specialisation which has been the rule in agriculture over the last few decades, the key word for transition is “diversity”, and this at every level; on the scale of farms, landscapes, regions, but also regarding the path followed by farmers, systems and markets.”

-------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.