On the morning of Saturday, September 19th 2015, Aurore Zengaïs was driving her scooter along the avenue des Martyrs in Bangui, the capital of the Central African Republic, on her way to work at the country’s social affairs ministry.

Suddenly, she lost control of her bike after being struck by another vehicle, and fell heavily onto the ground. She remembers having just the time to shout “Jesus!” as she went down.

It was around 9.40am, the avenue was dry and, the local gendarmerie report noted, at the scene of the accident it was 8.2 metres wide. The weather was clement, with the characteristic humid heat of the end of the rainy season. There were people about, but the bustle of the early morning rush hour had already passed.

As she came to her senses after the shock, Zengaïs felt a sharp pain in her left knee, where she saw a large open wound from which she was bleeding heavily. She quickly realised that she also had injuries to one ankle, her right arm and her face.

The vehicle that had struck her continued on its path for a few seconds before stopping. A soldier got out and came towards her. She then realised she had been hit by a French armoured vehicle weighing several tonnes.

At the time, the French army had been present in the Central African Republic (CAR) since nearly two years, after France’s then president, François Hollande, had launched Operation Sangaris in December 2013 to contain a bloody civil war led by rival Muslim and Christian militias. The strife in the former French colony, with a population of around 4.7 million, was threatening with a vast humanitarian crisis.

The accident that September morning drew a crowd, which soon became angry, with insults directed at the French troops, considered by some of the population to behave arrogantly. According to Aurore Zengaïs, 42, the soldier who had stepped out of the armoured vehicle showed little compassion to what had happened to her. “I shouted at him ‘What have I done to you for you to knock me over like that? Do you want to kill me?’,” she recalled. “He didn’t speak a word. He remained like that, with his weapon, all his gear, very proud, without helping me.”

Enlargement : Illustration 1

To stem the haemorrhage from her knee wound, Zengaïs took off the scarf keeping her hair in place and wrapped it around her leg. Fortunately for her, the accident had occurred just in front of a police station, from where officers had quickly emerged. Helped by local youngsters, they carried Zengaïs to one of their vehicles and rushed her to hospital where she was operated upon.

In French defence ministry documents about the accident, Zengaïs’s case is now described as “definitive transactional protocol N°5525”. It is among the files established for incidents of physical or material damage caused to innocent civilians by French forces during missions abroad, and which can range from deaths, loss of limbs and wounds from stray bullets, to damaged building facades and vehicle collisions. The reported incidents are recorded, costed, and “compensated”.

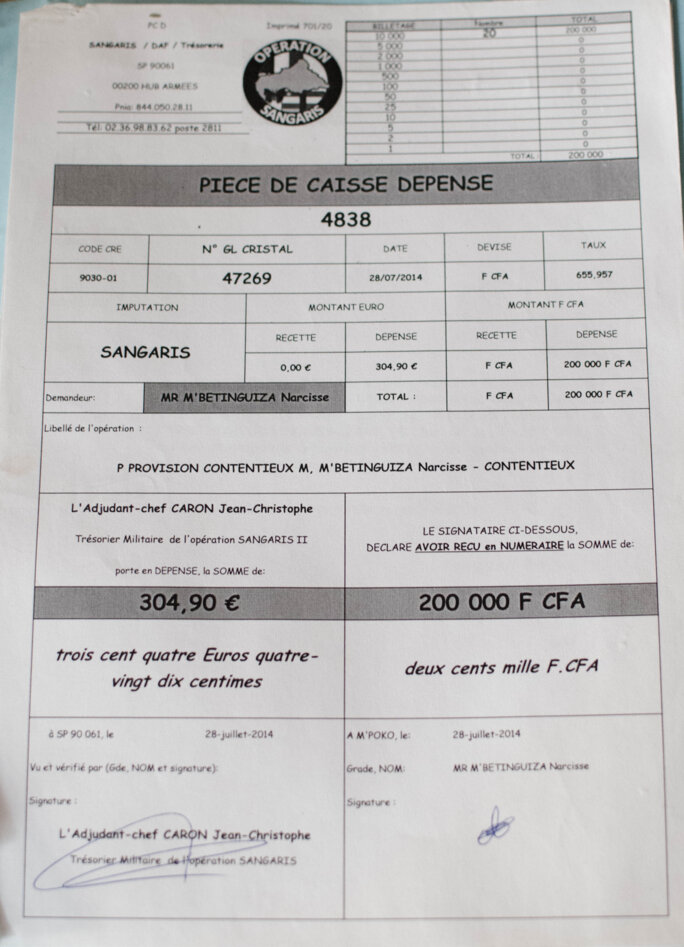

Mediapart has seen the compensation documents relative to the case of Zengaïs, signed by the military treasurer for Operation Sangaris, which shows she was paid damages totalling 4,131.09 euros.

The defence ministry keeps the compensation sums confidential, and no citizen or member of parliament has the right to consult, or control, the criteria of the calculations. Yet beyond the fact that the payments are made from the public purse, they also concern the country as a whole regarding the manner in which it treats those it has killed, wounded or deprived of their assets.

Mediapart has obtained access to numerous official documents and, cross-checking these with witness accounts, is able to reveal here for the first time some of the sums paid out. These include 2,752 euros paid in compensation to the victim of a stomach wound from a bullet during France’s peacekeeping operations in CAR. The sum of 15 euros was paid to a person who was the subject of a violent arrest in the Ménaka region of Mali, in west Africa. Around ten euros was paid to an NGO for bullet impacts on one of its vehicles, also in Mali. During an operation in Afghanistan, a local family whose land was occupied by French troops was paid compensation of 100 euros per day.

Confidential records in French military archives, drawn up by the ministry’s legal department, also reveal that a total of “about 350,000 FF [editor’s note, French francs, the sum here equivalent to about 53,400 euros]” was paid “after a mission of assessment on the ground” in compensation to civilians in the aftermath of “Operation Azalée”, a counter-putsch operation in the Indian Ocean island state of Comoros in 1995 to oust a government installed by French mercenary Bob Denard.

Between 1996 and 1998, a total of 868,200 euros was paid out in compensation for innocent victims of French army actions during its interventions in the war-torn former Yugoslavia. That sum was in response to about half of the 664 claims submitted, the others being rejected.

One compensation award concerned the 1983-1984 “Operation Manta” in Chad, when French troops were sent to the country to defend its government from advancing Libyan and rebel forces. The accidental killing of Chadian civilians resulted in the families of each victim being offered 70 heads of cattle.

The cases identified by Mediapart are of course not an exhaustive account of such payouts, but they illustrate that agreeing compensation, and the amount, for a person’s death, wounding, or material damage is subject to haggling, and that when these are agreed it is often for strategic rather than moral reasons.

Aurore Zengaïs, sitting in her small and neat, cream-coloured office in the centre of Bangui, presented a plastic-covered photo album in which her injuries are pictured.

On the first of the photos, all taken by her children, she is seen with a bandage over her temple. The second is a close-up of her forearm covered in bruising. One by one the photos chart the progressive healing of her injuries and the scars they left.

She also showed Mediapart the medical certificate written up by the surgeon of the hospital where she was treated, and which records a “contused arc-shaped wound of 8cms from the inside of the left knee with ligamentary injuries”. It estimated that she would suffer a permanent loss of 30% of mobility in her knee.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

It was after she began walking again, firstly with the help of a crutch, that she began the process of seeking damages from the French, notably for the cost of her hospital fees and medicines. With documents including the CAR gendarmerie report of the accident, she set off to the Mpoko military base, close to Bangui airport, where the French army had set up quarters.

“The guards at the entrance told me they couldn’t let me in,” she said. It was subsequently through a lawyer her husband knew that contact was made with the French military.

Negotiations began over the question of how much her damaged knee was worth in compensation. The French army captain in charge of treating her case, communicating via email with his surprising informal address of “sangarisachat@yahoo.fr” (which can be translated as “sangaripurchase@yahoo.fr”), made his first offer: 2,500,000 CFA, the locally used currency, a sum equivalent to 3,811 euros.

The lawyer found through her husband and who represented her in the negotiations rejected the offer, arguing that the sum did not take into account the physical consequences of the accident, including the numerous scars Zangaïs was left with, which in insurance terms is an aesthetic prejudice. But the French army captain remained firm. “The offer made during our last talks will be definitive at this stage: 2,500,00 CFA,” he replied.

Six months later, after the discussions had reached a stalemate, she was invited to visit the Mpoko base to be examined by a French military doctor, who would establish an estimate of the permanent disability caused to her by the accident. This was evaluated at 30% and, one year after the accident, she was finally offered 4,131 euros in damages, which included 600 euros for her lawyer’s fees.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

The sum in fact represented half of what Zengaïs was entitled to on the basis of the CAR gendarmerie report of the accident. That had concluded that the French armoured vehicle had been at fault, causing the accident after by cutting in front of her too closely. But their French counterparts who had been sent to the scene concluded that they could not establish who was at fault, and under French procedure this meant that she was entitled to only 50% of whatever sum would otherwise have been agreed with her.

The incidents of compensation paid to civilians during Operation Sangaris, which ended in 2016, is far from unusual. Like practices in place with armed forces of other nations, the French army has for at least 20 years been engaged in compensating innocent victims of operations abroad. The total amount of these has never been made public. Questioned by Mediapart, the French defence ministry said this was to protect “the security and private life of the people concerned”. It would also shine a light on the number of collateral victims of the French armed forces.

Of the payments recorded in the archives of the French defence ministry, most were for traffic accidents. In the legal department’s document cited further above, one compensation award was for “the death of a young child killed in a road accident” in ex-Yugoslavia, “settled” after three years. There was no mention of the sum paid out to the child’s family. Questioned, the ministry declined to comment on the case.

When a Chadian woman's life was worth 35 heads of cattle

Details of compensation payments for accidents involving US armed forces have been made public, following a request for details of them filed under the Freedom of Information Act by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). In 2007, the NGO received from the Department of the Army a list of hundreds of cases of compensation awards over incidents involving US forces in Iraq and Afghanistan in 2005 (available on ACLU’s website here).

These reveal how the parents of a 12-year-old boy killed by the US army as he rode his bike close to the family’s farm in Afghanistan were awarded 2,500 dollars. The same year in Afghanistan, the grandmother of a six-year-old boy killed in a traffic accident involving US soldiers was awarded 3,000 dollars.

Between October 2005 and September 2014, the US army awarded a total equivalent to 4.4 million euros in “condolence payments”.

A handbook published by the US army’s officer teaching and training Combined Arms Center, entitled Commander’s guide to money as a weapons system, (subtitled Tactics, Techniques and Procedures) sets out various uses that can be made of funds in military operations, from financing local bodies to “warfighters”, along with practical advice and the regulations on doing so. On an opening page, it features a pertinent quote from now retired General David Petraeus, a former commander of the 101st Airborne division in the 2003 invasion of Iraq and later commander of US troops in Afghanistan, “Money is my most important ammunition in this war,” he said of the fighting in Iraq.

In Denmark, journalists Rasmus Raun Westh and Charlotte Aagaard used public information legislation to obtain and publish details of compensation awards by the Danish defence ministry. These showed that a woman in the southern Afghan province of Helmand, where the Danish army was engaged in NATO-led operations, was paid 6,700 euros over an incident involving Danish troops in which her five-year-old daughter died, her husband received leg wounds and her eldest daughter was wounded in the thigh. In another case in Helmand, the Danish authorities paid out 36,000 euros for the deaths of five people, including two children, who were victims of mortar fire from Danish troops.

While in France the precise sums are not made public, several elements indicate that compensation payments concerning all military operations by French armed forces amount to several million euros per year. In a 2016 report by France’s national audit body, the Cour des comptes, on French military operations abroad over the period 2012-2015, what is called “the spending on litigation” by the defence ministry – which includes both local civilian claims and those of French troops wounded or injured in action – amounts to around 15 million euros per year.

Beyond physical accidents, the French armed forces also pay compensation to the owners of property requisitioned by troops for military operations, such as using the roof of a home to position a machine gun, or a house or field occupied by a platoon. One military source, whose identity is withheld here, confirmed to Mediapart that in the early 2010s, the French army operating in the northeast Afghan province of Kapisa paid the equivalent of about 100 euros per day to homeowners of houses they chose to occupy.

Those who evaluate compensation for physical and material damage, as well as the occupation of property, are called “officers in charge of litigation”. They are attached to the “Commissariat of the armed forces”, a body that manages the administration, finances logistics and legal matters within the French military. In a write-up about the work of these litigation officers published on the defence ministry’s website, it noted that compensation negotiations could be “turbulent” at times. It quoted one of the officers, who was sent to Afghanistan in 2014. “One sometimes finds oneself as if in an Afghan market negotiating the price of a carpet,” he said. On the broad issue of compensation awards, he explained: “The aim is to reach an agreement with the victim, so as to extricate the French state from all future responsibility.”

In the case of Narcisse Mbetinguiza, a taxi driver in CAR, negotiations involved not a carpet but the price of a bullet wound to his stomach which pierced his abdomen. He would finally receive 2,732 euros in compensation for the shooting. He was hit by a 5.56 mm bullet in the region of his naval as he came out of his home in the capital Bangui on May 3rd 2014. He was about to visit his brother to borrow a USB flash drive when a young French soldier, part of the Operation Sangaris force, mistook him for a militiaman on the run.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

In the initial negotiations, before the final award, the French captain in charge of settling Mbetinguiza’s claim overlooked the inclusion of damages for the suffering caused to the taxi driver and the prejudice caused to his future working life, both of which are written into the local legal code of insurance for claims for such incidents. It was only after a lawyer intervened on his behalf that these considerations were included.

In the written exchanges between the French captain and Mbetinguiza’s lawyer, the damages for the pain and suffering he endured, and also the aesthetic damage caused, were calculated “on the basis of local minimum salary” the captain explained, “since an individual suffers with the same intensity whatever their earnings”.

In the preamble to a 1995 manual of guidance for the officers in charge of compensation claims, the French defence ministry’s general administration warned that “indemnity claims […] are frequently exaggerated”. In a section of the document dedicated to “Compensation in the case of a fatal accident”, it notes that claims by parents and siblings “can be favourably received” but that those “formulated by fiancés or concubines must be met with caution”.

In the case of collateral damage to civilians abroad, the defence ministry is able to keep payouts relatively low by invoking the notion of respecting local customs, in an appearance of rectitude. That notion was applied to the awards made to Narcisse Mbetinguiza and Aurore Zengaïs, which were based on indemnity terms set out by the Francophone “Inter-African conference on insurance markets”. But this poses a moral issue, namely that of calculating the blood money on the basis of local standards of living whereas, as the Operation Sangaris captain commented, “an individual suffers with the same intensity whatever their earnings”.

While Narcisse Mbetinguiza was initially offered 206.50 euros for the bullet wound he received, an incident of the sort involving a French national would have been the subject of an award of between 8,000-20,000 euros, according to calculations based on a 2016 reference manual for indemnity payments by France’s appeal courts, and edited by France’s national magistrates’ training school, the École nationale de la magistrature.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

In a little-known book on the activities of the French military assessors of damages awards abroad, two of them recalled how the compensation for the collateral death of a woman in Chad during the 1983-1984 “Operation Manta” was the offer to her family of 35 heads of cattle. “In the case of the accidental death of a Chadian caused by a French soldier”, the book notes, the compensation award for the family would be made “on the basis of a table established by customary law, according to gender”. That local table is given in the book as being 70 heads of cattle for the death of a man or boy, and 35 heads of cattle for the death of a woman or girl. At the time of “Operation Manta”, the book says, the average price of a head of cattle was 400 French francs, equivalent to about 60 euros.

While in CAR or in Mali local insurance codes are used to calculate compensation awards, based on the minimum legal wage, if a French soldier is accused of committing crimes in those same countries they are not subject to local justice systems. Before sending troops on operations in CAR and Mali, France signed agreements with the governments of those countries, called a “status of forces” agreement, whereby French soldiers accused of crimes there can only answerable before the justice system in France.

The payment of compensation is less out of a moral concern than an approach of “winning hearts and minds”, as described by the then French defence ministry’s head of legal affairs, Claire Landais, in a 2013 interview published in the French public administration review, the Revue française d’administarion publique. She told the publication that damages awards to civilians abroad “justify themselves notably by the necessity of guaranteeing a good image of the forces amongst this population”.

Beyond a guaranty of that “good image” is also the guarantee that the collateral victims will not later launch legal proceedings against the French state. Indeed, the payouts are made on condition that the victims give up in writing their rights to any future litigation over the incident concerning them. In the case of Aurore Zengaïs, before receiving the 4,131 euros finally awarded to her she had to sign a documents in which it was agreed that: “The parties relinquish all action, intention and any recourse relative to the same events, and withdraw themselves from any legal proceedings or ongoing action engaged.”

In a letter sent by the French army to Narcisse Mbetinguiza, regarding an initial payment of just more than 300 euros, it stated: “The present offer of settlement is made under the express condition that in no event can it be produced in legal action against the [French] State.”

For Zengaïs, “It’s not a question of money, it is also a question of compassion.”

“The French soldiers should know that we are human beings just the same as them,” she added. “If they want to come and help us, they have only to help us. If they don’t want to help us, they have only to stay quietly at home.”

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse