When news does emerge from those held within Iranian prisons it is often miserable, as the family and friends of Fariba Adelkhah know only too well. The Paris-based anthropologist of French-Iranian dual nationality is being held in atrocious conditions in the notorious Evin prison in the outskirts of Tehran. Meanwhile, the detention conditions are even worse for Australian-British academic Kylie Moore-Gilbert, who was recently moved from Evin to Qarchak, regarded as the harshest women’s prison in Iran, located in an area of desert south of the capital.

Moore-Gilbert was arrested September 2018 for alleged violation of Iran’s national security, and Adelkhah was detained in June last year, along with her partner and fellow academic researcher Roland Marchal, over similar allegationss. Marchal was released earlier this year, when he returned to France.

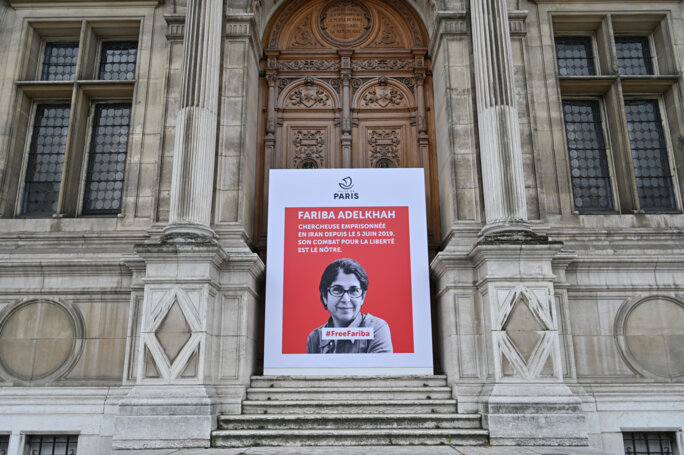

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Adelkhah, 61, an anthropologist and specialist on Iran, is a research director, like Marchal, at the Centre for International Studies at the prestigious Paris political sciences school Sciences Po. In June this year she lost her appeal against a five-year prison sentence pronounced one month earlier for allegedly “conspiring against national security”. Following that, Adelkhah was removed from solitary confinement Evin prison in a section controlled by the Islamic Revolutionary Guards.

According to news received by members of her family, she is now kept among inmates accused of common crimes, and shares living space with around 40 other prisoners. Her family said that tensions run high in the cell, where she must avoid certain prisoners because of threats of violence, notably when food is served.

It is reported that among her co-prisoners in the cell is the human rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh, 57, who has defended various opponents of the Islamic regime including women who refused to wear a headscarf, and who was last year convicted of seven charges that together carried a total of 38 years in prison, when she was ordered to receive 148 lashes. Also reportedly with her in the cell are environmentalist activists.

“Even if she was expecting to be convicted, Fariba Adelkhah was struck low when the verdict was pronounced and confirmed on appeal,” said her friend and colleague Jean-François Bayart, a political sciences lecturer and researcher who co-presides the France-based committee of support for Adelkhah. “Fortunately, she can have a weekly visit from her family and phone contact with them.”

Adelkhah is reportedly concerned that neither she nor her lawyer has received official notification of her conviction – both the initial sentence and again on appeal – which means it is impossible for her to mount any ultimate appeal.

“Fariba has the impression of fighting against an eiderdown, because all her requests come up against the incapacity of the justice system to reply,” added Bayart. “Because everything depends upon the black box of the Revolutionary Guards, the judges being only the executive arm of that organisation which is itself divided.”

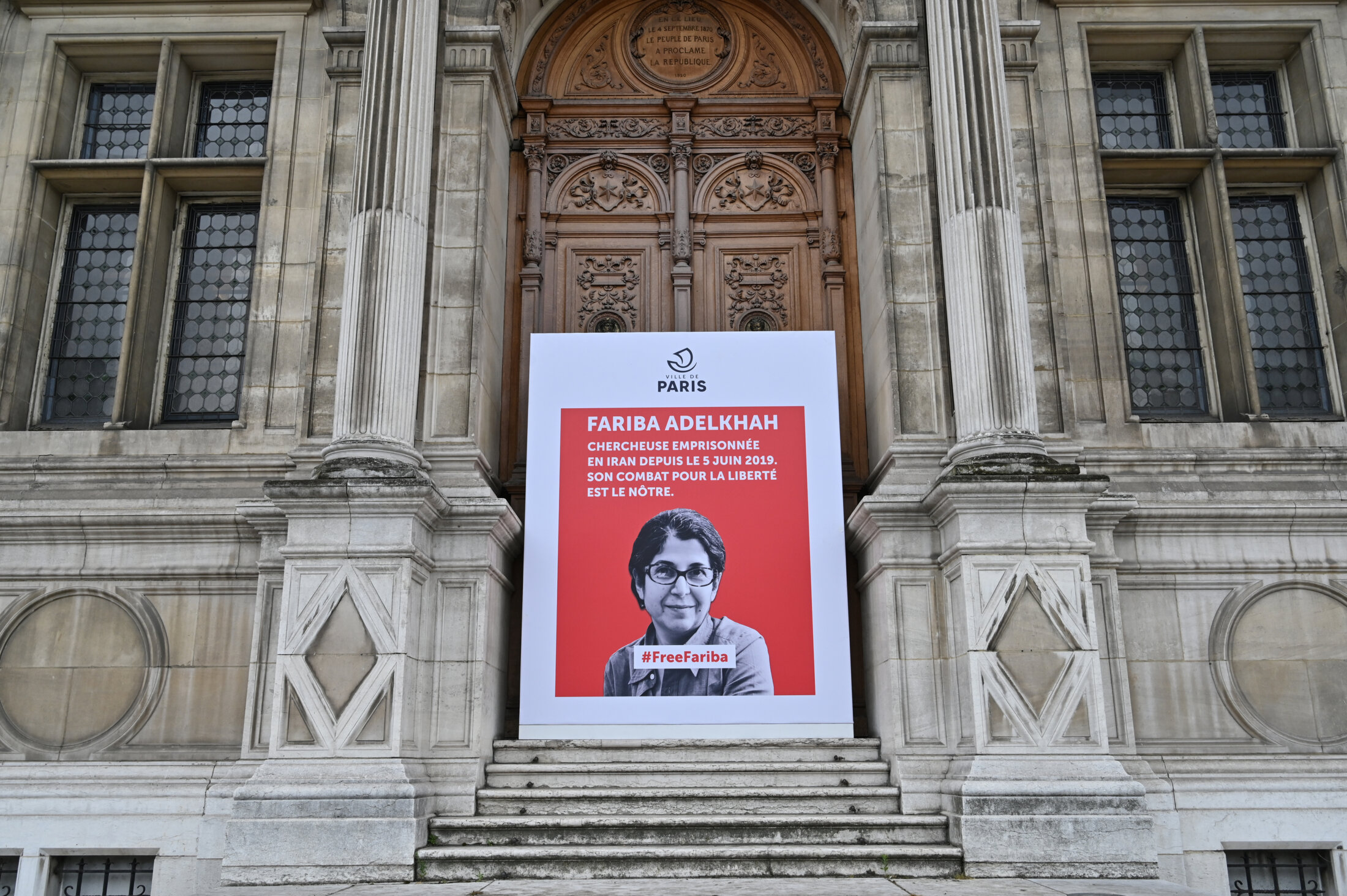

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Political scientist Béatrice Hibou, who works at the Sciences Po school and is a research director with France’s scientific research centre, the CNRS, is also a member of the committee of support for Adelkhah. She said French diplomatic efforts to help the French-Iranian researcher continue, even though the opportunities to do so were slim. “But it cannot provide any assistance in favour of a citizen considered to be exclusively Iranian by her jailors,” she said. “The American and Iranian electoral agendas are hardly favourable [Editor’s note, while presidential elections are due in the US in November, and in Iran in 2021], and the spectacular rapprochement between Tehran and Beijing further depreciates the negotiating position of Paris which, moreover, has more to fear than hope for regarding the actions of the United States in the region.”

Meanwhile, detention conditions worsened significantly last month for Kylie Moore-Gilbert, a lecturer in Islamic studies at Melbourne University’s Asia Institute, who was arrested in 2018 and given a ten-year sentence for spying offences, which she has strenuously and repeatedly denied. After two years in Evin prison’s Ward 2A, run by the Revolutionary Guards, she was secretly transferred on July 25th to Qarchak. Even her lawyer was not informed of the move.

Qarchak, a prison holding mostly common criminals, is notorious for its overcrowded conditions and the isolation of its location. “The lack of medical care, dental care, and regular checkups, poor hygiene, and a great number of prisoners, has caused several issues,” reported the Iranian Human Rights Activists News Agency (HARANA), an organisation opposed to the regime, in a report on the prison published in March this year. “The poor quality of food, drug use and easily accessible narcotics, not isolating prisoners with a contagious disease from others, rape, and negligence of the prison authorities are some of the issues of this prison […] The prison does not separate inmates according to the crimes committed and this leads to violence, thus worsening the situation as they are not offered medical services and are subjected to torture.”

Citing information from what it said were sources inside the prison, and from prisoners after their release, HARANA’s report added: “The prison’s seven sections contain more than 1,400 prisoners with 120-300 prisoners held in each section, although the capacity of each section is 100 inmates. Some of these prisoners are incarcerated along with their children while the number of prisoners increases every year. Each ward has 10 cubicles where each has four triple bunk beds. Several prisoners have to sleep on the floor.”

'Hostage takings are a systematic policy of Iran'

“Our fear is that she becomes contaminated by the coronavirus,” said Jean-François Bayart, co-president of the support committee for Fariba Adelkhah, on the subject of the transfer of Moore-Gilbert to Qarchak. “To send her to Qarchak, at the height of summer, is virtually a death sentence.” HARANA, among others, has chronicled the spread of Covid-19 into the prisons of Iran where around 100,000 inmates were temporarily released early to reduce its propagation.

According to a BBC report this month, official figures greatly underestimate the toll of the epidemic in Iran. The investigation by the BBC’s Persian Service, citing confidential Iranian government data it received, found that the number of deaths in Iran from Covid-19 infection was by July 20th almost 42,000, nearly three times more than the 14,405 indicated in official health ministry figures. But even the ministry’s figures place Iran as the Middle East country which has been the worst-hit by the virus.

According to a report published last month by British daily The Guardian, after arriving at Qarchak, Moore-Gilbert held a phone conversation with Reza Khandan, the husband of jailed human rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh. The daily said it had verified a recording it received of the conversation, in Persian, with colleagues of the academic. “I can’t eat anything, I feel so very hopeless, I am so depressed,” she was quoted as saying.

“I don’t have any phone card to call,” she reportedly complained. “I’ve asked the prison officers but they didn’t give me a phone card. I [was last able to] call my parents about one month ago.”

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Earlier this year, The Guardian cited from letters handwritten by Moore-Gilbert for the attention of the Iranian authorities and which were smuggled out of Evin prison where she was then being held. “She writes that she has little money to buy food, is denied phone calls to her family, and that her failing physical and mental condition has seen her repeatedly transferred to hospital,” reported The Guardian. She also wrote a firm rejection of an offer made to her to become a spy for the regime. “I am not a spy. I have never been a spy and I have no interest to work for a spying organisation in any country. When I leave Iran, I want to be a free woman and live a free life, not under the shadow of extortion and threats.”

Meanwhile, Australia’s ambassador to Iran, Lyndall Sachs, was able to visit Moore-Gilbert on August 2nd, and reported that she was well, with access to medical facilities, and books.

Moore-Gilbert was arrested at Tehran airport in September 2018 as she was about to leave Iran after taking part in an academic conference she had been invited to in the city of Qom. She had been reported to the authorities by one or more delegates at the conference, and also by a person she interviewed as part of her research work, as being “suspicious”. At the end of a secret trial she was convicted of espionage, when the ten-year jail sentence was handed down.

French-Iranian researcher Fariba Adelkhah was also initially charged with spying, although that was later dismissed before she was found guilt of “conspiring against national security”. A notable contrast between the two cases is that while Adelkhah has received the public support of the Sciences Po school and numerous colleagues, there has been relatively little mobilisation on the part of academics in Britain or Australia, beyond that of her close friends, for Moore-Gilbert, a graduate of Cambridge university. Nor has there been any cross-Channel cooperation for mounting a joint campaign of support for both women.

Meanwhile, the Australian authorities have favoured adopting a low profile over Moore-Gilbert’s case. “We believe the best chance of resolving Dr Moore-Gilbert’s case lies through the diplomatic path and not through the media,” said a spokesman for Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade earlier this month. So far, however, that has failed to produce a result.

“Each go about things in their own manner, it’s incredible, the more so in that these hostage takings are a systematic policy of Iran,” said Jean-François Bayart. There are estimated to be around ten people with dual French nationality held in Iran’s prisons, along with a small number of French tourists.

In unsubstantiated claims, sources citing British academic circles suggested that Prime Minister Boris Johnson has let it be known that he wants academics to keep a low profile over the Moore-Gilbert case.

While it is not publicly known what Iran may have demanded in exchange for Moore-Gilbert’s release, in the case of Fariba Adelkhah it appears that Tehran is seeking the release of an Iranian diplomat currently imprisoned in Belgium. He was arrested over his alleged involvement in the preparation of a terrorist attack in a Paris suburb targeting the militant Iranian opposition group, the People’s Mujahedin.

The release of Adelkhah’s partner Roland Marchal in March this year came about in a simultaneous prisoner swap. Marchal, a sociologist specialised in the histories of African civil wars, was freed within hours of France releasing from prison an Iranian engineer, Jalal Rohollahnejad, who was detained while awaiting extradition to the US on charges that he tried to smuggle technology equipment into Iran in violation of sanctions by Washington.

Marchal was arrested in June 2019 at Tehran airport upon his arrival to visit Adelkhah while she was on a trip to the country – just one month after a French appeals court ruled in favour of Rohollahnejad’s extradition to the US.

After his release, Marchal said he had at one point been accused by the Iranian authorities of seeking to influence Tehran’s defence policies. This was apparently because he had invited the head of an Iranian think tank on African affairs to a conference in Paris. What Marchal did not know, he said, was that the father of his guest was an Iranian general and an advisor on military matters to Iran’s ‘supreme leader’ Ali Khamenei.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this report can be found here.