In one of its four-part series of investigative reports on France’s exploitation of Haiti over the course of the 19th century, published in English, Creole and French, The New York Times focuses on the role played by the Société Générale de Crédit Industriel et Commercial between 1875 and the start of World War I.

Established through a decree by Napoleon III on May 7th, 1859, the bank grew to become a leader in the Paris financial marketplace, known under the name of Crédit Industriel et Commercial (CIC), eventually nationalised in 1982 and finally privatized and acquired by Crédit Mutuel in 1998.

The revelations by The New York Times are eye-opening, especially since France has generally avoided shining a light on the more controversial episodes in the country’s history. These revelations also confirm the enormity of the ransom demanded by France of its former slaves, starting in 1825 and for decades thereafter, constituting the price of their freedom and the indemnification of slaveholders: undoubtedly totalling around USD 560 million in current terms (around 525 million euros), as recently noted by Mediapart. The shameful and little-known role of the CIC in this history deserved to be fully exposed.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

It is nevertheless important to remember at least two points when considering the revelations. Firstly, some of the facts have not yet been established and not all of the hypotheses put forth by The New York Times (NYT) have been verified. Second, and more importantly, reading the article might lead one to conclude that the CIC’s history is just one of the many events that befell Haiti when the country gained independence, and that this bank took advantage of exceptional circumstances to enrich its shareholders on the backs of the Haitian people. However, such a simplified explanation misses the point. The CIC behaved poorly, as did all the French colonial banks during this period, with all of them using more or less the same mechanisms.

That is one of the major takeaways from the investigative reporting about on CIC by the NYT. In a roundabout way, it opens the door to revisit this very dark past of the French colonial banks, which in Haiti as well as in Asia, Africa and the other parts of the Antilles built their fortunes using this same exploitative system.

Unprecedented release of diplomatic archives

Until now, little was known about the bank’s role in Haiti, since its own archives are virtually non-existent on the subject, as noted by Nicolas Stoskopf, professor emeritus of contemporary history at the University of Upper Alsace. The author of a 2009 book celebrating the CIC’s 150-year anniversary, Stoskopf himself hit a dead end while researching the tumultuous history of relations between Haiti and the bank.

In his book (which is available here on the HAL-SHS public archive site, or see immediately below), the historian only briefly mentions the loan to Haiti raised by the CIC in 1875.

With access to previously unknown diplomatic archives, the NYT recounts a story whose most scandalous details had never before seen the light of day.

The bank’s predatory practices were implemented in two ways. First, in 1875, reports the US daily, “C.I.C. and a now-defunct partner had issued Haiti a loan of 36 million francs, or about $174 million today. […] Beyond bricks and steel, Haiti earmarked about 20 percent of the French loan to pay off the last of the debt linked to France’s original ransom, according to the loan contract. ‘The country will finally come out of its malaise,’ the Haitian government’s annual report predicted that year. ‘Our finances will prosper’.”

The article goes on to expose: “None of that happened. Right off the top, French bankers took 40 percent of the loan in commissions and fees. The rest paid off old debts, or disappeared into the pockets of corrupt Haitian politicians. [...] In that way, the loan helped prolong the misery of Haiti’s financial indentureship to France. Long after the former slaveholding families considered the debt settled, Haiti would still be paying – only now to Crédit Industriel. The second legacy was felt more immediately. The loan initially obligated the Haitian government to pay C.I.C. and its partner nearly half of all the taxes the government collected on exports, like coffee, until the debt was settled, effectively choking off the nation’s primary source of income.”

Full powers to the French bank

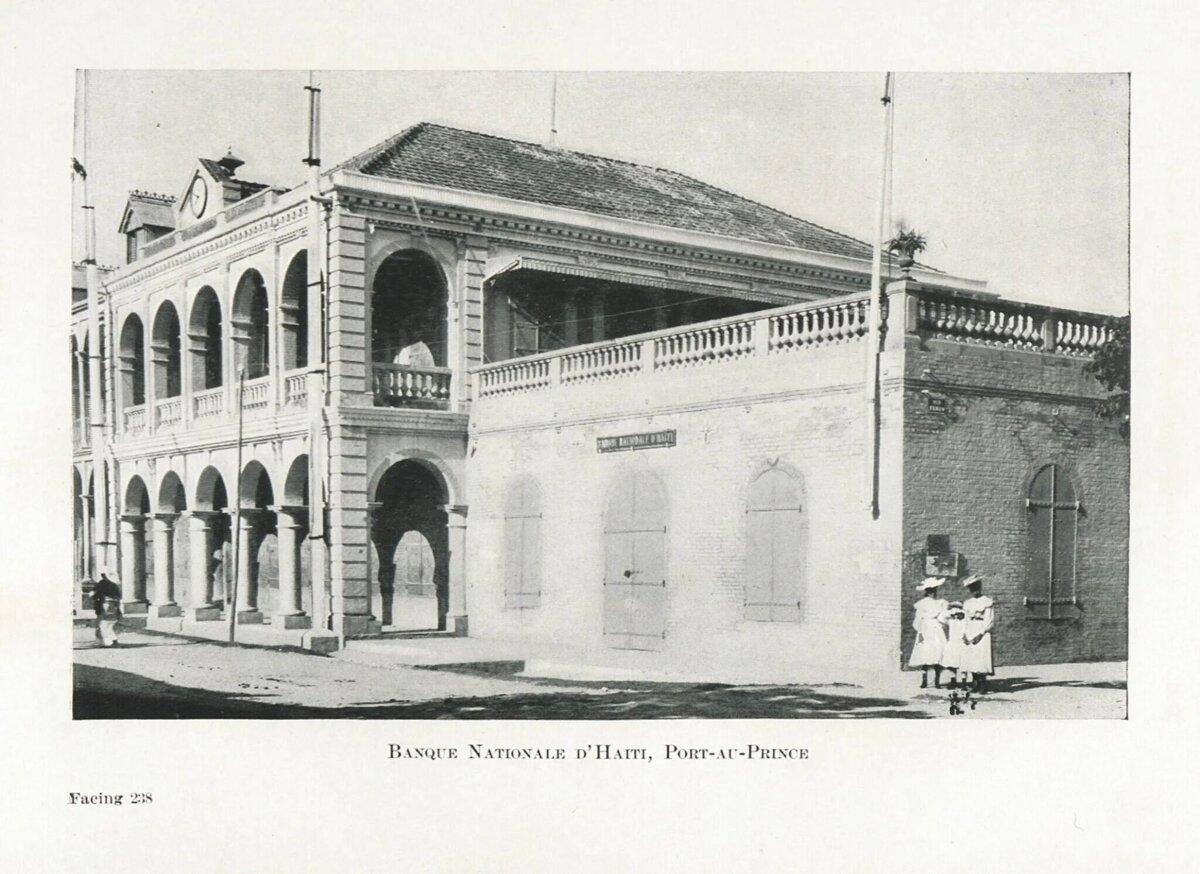

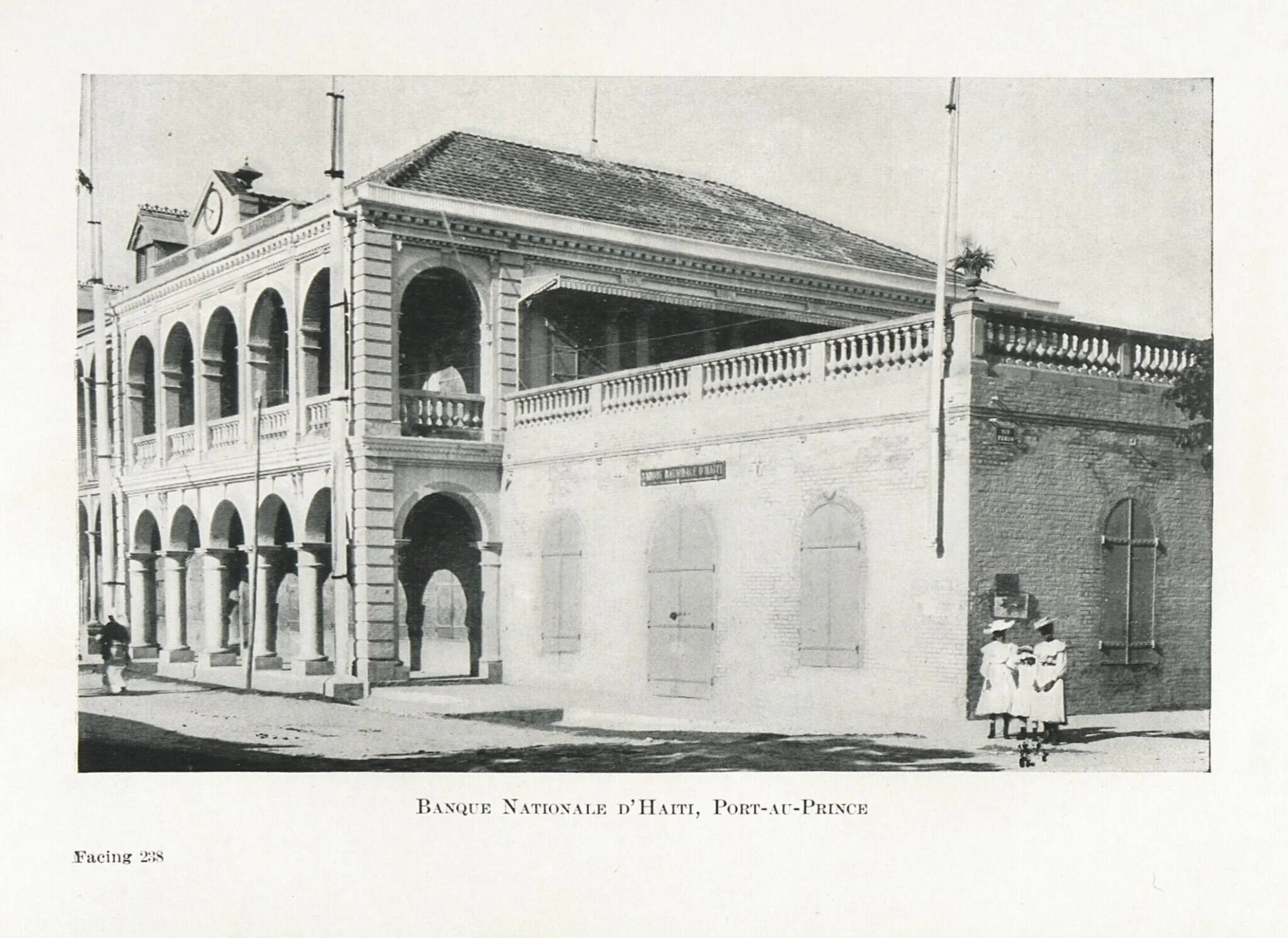

The predatory practices continued through the creation of the Banque nationale d’Haïti (National Bank of Haiti) in 1880. The only thing “national” about the bank was the name, since the bank was created by the CIC, with the headquarters located in the same Paris offices of the French bank then chaired by Henri Durrieu (1821-1890).

As noted in the NYT article, “the contract establishing Haiti’s national bank reads like a series of giveaways. Durrieu and his colleagues took over the country’s treasury operations – things like printing money, receiving taxes and paying government salaries. Every time the Haitian government so much as deposited money or paid a bill, the national bank took a commission. [...] Durrieu was the first chairman of a board that included French bankers and businessmen, including Édouard Delessert, a great-grandson of one of the biggest slaveholders in Haiti’s colonial history, Jean-Joseph de Laborde”.

Uncovered by the NYT, the decree signed on September 10th 1880 by Haitian president Lysius Salomon (1815-1888) effectively gives full powers to the French bank (see immediately below, in French).

In article 1 of the decree, the Haitian government grants the concession “the right to create and operate a national bank under the name of Banque nationale d’Haïti” to “Henri Durrieu, the Chairman of the Board of Société Générale du Crédit Industriel et Commercial, acting both in this capacity and on behalf of a Committee of Capitalists that he represents”.

A 'Committee of Capitalists' in charge of Haiti's national bank

The ensuing articles then define the terms of the concession. It is granted for a period of 50 years. Article 3 stipulates that “the bank shall be established as a French limited liability company [...]; its headquarters shall be in Paris, where the Board of Directors will meet”. Then in article 9, the Haitian government gives up a major sovereign function: “The bank has the exclusive right to issue banknotes.”

Article 15 states that “the Bank shall be responsible for the Haitian government’s Treasury service and, thereby to receive deposits of all amounts due to the State, notably customs duties on imports and exports,” with all of these transactions generating commissions for the bank.

In essence, under this astonishing decree, the CIC controlled the National Bank of Haiti and thereby profited from the Haitian government’s finances.

The list of subscribers, held by Henri Durrieu, in the national bank confirms that the new institution was owned by French investors, organized by the CIC, or more precisely, to use the phrasing of the presidential decree, a “Committee of Capitalists”.

As the NYT further reports: “Durrieu’s gamble paid off. At a time when typical French investment returns hovered around 5 percent, board members and shareholders in the National Bank of Haiti earned an average of about 15 percent a year, according to a New York Times analysis of the bank’s financial statements. Some years, those returns approached 24 percent. Durrieu made out handsomely. His contract with Haiti granted him thousands of special shares in the national bank, worth millions in today’s dollars.”

The daily added: “By the early 20th century, half of the taxes on Haiti’s coffee crop, by far its most important source of revenue, went to French investors at C.I.C. and the national bank. After Haiti’s other debts were deducted, its government was left with pennies – 6 cents of every $3 collected – to run the country. The damage was lasting. Over three decades, French shareholders made profits of at least $136 million in today’s dollars from Haiti’s national bank – about an entire year’s worth of the country’s tax revenues at the time, the documents show.”

CIC offers the securities of the Haitian loan to investors

The NYT report, which sheds light on very important new facts, nevertheless contains a few flaws. The historian Nicolas Stoskopf points out that there is undoubtedly some confusion regarding the CIC’s charter. The bank at that time was a depository institution, since loans accounted for only 2% of its assets. Therefore it was not the bank that granted a loan to Haiti in 1875 with an eye toward collecting interest. On the contrary, the bank paved the way for French savers to subscribe to the Haitian loan and acted only as an intermediary, taking a commission in the process.

As one expert on the subject, whose name is withheld, notes: “To be clear, the CIC apparently did not grant a 36-million-franc loan to Haiti in 1875 but instead raised a loan on behalf of the Haitian government that it then offered to its clients and French investors. That is a big difference. The CIC did not invest its own money but that of investors looking to buy securities, and the CIC was remunerated solely through commissions and coupons – not through interest payments. Accordingly, interest payments were never made to the CIC but instead to loan-holders – the subscribers were mainly French investors. Yet that is the principal accusation made by the Times about the CIC at the time.”

Although the NYT article does point out that the then-president of CIC grossly enriched himself, it glosses over the possibility of a ‘bank within the bank’ scheme whereby the president claims to be acting on behalf of his institution when in fact he is acting in his own interest. Indeed, this practice of co-mingling the company’s business with the interests of its president was commonplace in those days, and not only in the banking sector.

In fact, this confusion arises in the aforementioned bank charter. In article 5, it is stipulated that Henri Durrieu, “acting in his name” and not in the name of the CIC, contributes to Haiti’s national bank “the Bank concession granted to him by the Secretary of State to the Finance Department”. Article 5 also notes: “As consideration for his contribution, research and assistance, as well as for having guaranteed the subscription of the Bank’s capital, 25% of the profits generated by the Bank over its lifetime shall be granted to Mr. Durrieu, acting in his name.” In other words, CIC’s sins are primarily those of its president, who clearly acted in his own interest.

The colonial banks were created from the abolition of slavery

But the larger point is something else entirely. When first reading about the CIC’s improprieties, one might think they involve a one-time event in which the French bank profited from Haiti’s misfortune. Under this narrative, the singular acts of one particularly avaricious bank were a function of unique circumstances in Haitian history. Yet nothing could be farther from the truth. The CIC’s actions are but one episode among many others in the oft-forgotten history of French colonial banks, which were created as a result of the abolition of slavery.

The history of the Banque de Martinique and the Banque de Guadeloupe are another example. Their origins, as described by Alain Buffon, associate professor at the University of the Antilles and Guyana, in le Bulletin de la société d’histoire de la Guadeloupe (No. 132, May-August 2002) are very revealing.

“From 1853 to 1944, Guadeloupe and Martinique benefited from an autonomous monetary system with a central bank that enjoyed a monopoly on the issuance of banknotes in the colony and a special banknote with the status of legal tender throughout the territory,” writes Buffon. “The old colonial banks were born from the abolition of slavery. Following the 1848 revolution, one of the provisional government’s first concerns was to establish a commission to prepare the emancipation statute for slaves in all of the Republic’s colonies. This commission was chaired by Victor Schœlcher [1804-1893], the Undersecretary of State of the Navy and Colonies. The April 27th decree stipulating that no French territory may be home to slaves resulted from the work of this commission.”

We believe that they are owed compensation.

Indeed, at that time colonists demanded – and not just in Haiti – to be indemnified for the abolition of slavery. And Victor Schœlcher himself agreed: “Whatever repugnance one may feel at the thought of indemnifying slaveowners … we believe that they are owed compensation … we cannot forget that it [slavery] was instituted and maintained by law”. But the “indemnification cannot be granted solely to property; it must also be given to the entire colony so that it benefits both the owner and the worker".

This latter reservation expressed by Schœlcher was nevertheless ignored. The law of April 30th 1849 indeed provided for indemnification granted to slaveholders, notably through the measure described here by Alain Buffon: “Of the total indemnity benefiting slaveholders, one-eighth of the 6 million annuity allocated shall be withheld to create the capital of a credit institution. In exchange for this withholding, each indemnified colonist shall receive shares in the Bank.”

In France’s Caribbean islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe, the colonists therefore no longer owned slaves but became the principal shareholders of the local bank, to which the government granted the monopoly on the issuance of banknotes.

In this manner, the first colonial banks with very broad powers were created at the end of France’s Second Republic (1848-52), and start of its Second Empire (1852-70). Although colonists no longer had their free labour, their economic and financial domination was fully guaranteed in a crushing manner. In Martinique, this provision is what consolidated the overwhelming economic power of the so-called békés, the upper middle-class creole population which descended from the first colonists.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

The Banque de La Réunion was established at the same time and under the same conditions. Many years later it wound up being acquired first by the Crédit Lyonnais, then the Caisses d’Epargne, currently part of BPCE.

Thus the first colonial banks were created. This pattern was repeated in subsequent years as the CIC created other colonial banks, while the Haitian national bank remained the most scandalous example as its scope of activity was in a then supposedly sovereign country.

The Banque de l’Indochine scandals

Yet this bank sought to repeat the same efforts in numerous countries. As noted by Nicolas Stoskopf in his book, the bank participated in the creation of “the Mexican National Bank (1881) and the Madrid General Bank (1881), whose shares it held up until 1887”. The historian added: “In Tunisia, it sought to create a bank of issue in early 1884 along the lines of the Banque de l’Indochine, but the Bank of Tunisia, founded at that time with the help of the Société Marseillaise and the Société de Dépôts, did not obtain this privilege.”

The other major project to see the light of day was the one involving the Banque de l’Indochine, which the CIC completed in 1875, in conjunction with another bank, the Comptoir National d’Escompte de Paris. The new bank was built using the same model that would be retained several years later for Haiti. It enjoyed the right to issue currency, the piastre, which circulated in all French colonies in the Far East. This right was gradually extended to many other French colonies up until 1948, notably French Polynesia and New Caledonia. Another shared trait between the two banks was that the Banque de l’Indochine was also managed from Paris, since its headquarters were in the CIC offices themselves.

This situation of colonial domination granted to a bank, going so far as to relinquish the country’s monetary sovereignty, naturally lends itself to conflicts of interest and scandals. In the CIC’s long history, one of these scandals ended up causing a major stir many years later, namely the black market trading of piastres, which is at the heart of the intrigue splendidly laid out in the recent novel by Pierre Lemaitre, Le Grand Monde (published by Calmann-Lévy, 2022). Since the piastre’s official exchange rate for transfers between France and Indochina was well above the real value of the currency in the French colony, a vast black market arose in the years 1948-1953, to the detriment of the public finances and enabling many racketeers to enrich themselves.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

Indeed this historical review of French colonial banks is also noteworthy because it provides a fresh look at some of the dark moments in the history of French capitalism. In Histoire secrète du patronat de 1945 à nos jours (La Découverte, 2014), for example, Benoît Collombat retraces the actions of Sylvain Floirat (1899-1993), a businessman known for having played an instrumental role in the success of a series of companies, from Matra to Europe 1 and including the Aigle-Azur airline (later acquired by UAT and then Air France), and also tells how he began to make his fortune in the opium trade transiting through Indochina using Aigle-Azur planes, and undoubtedly through the black market trading in piastres.

In any event, we know how the piastres scandal turned out. As is also described in the Pierre Lemaitre novel, it became clear that the Viêt-minh also benefited from the illegal currency trading and thereby financed its arms purchases … all on the backs of French taxpayers.

This history ultimately diverged to where it no longer involved CIC. In 1974, Banque de l’Indochine merged with Banque de Suez to become Indosuez bank, which in turn merged with the former Crédit Lyonnais in 2004 under the auspices of Crédit Agricole.

The case of Banque Internationale pour l’Afrique Occidentale

To this list of colonial banks several other institutions must also be added, notably the Banque Internationale pour l’Afrique Occidentale (BIAO). As noted in a Wikipedia article page, Napoleon III, through a December 21st 1853 decree, created the Banque du Sénégal, which was initially controlled by former slaveholders indemnified through share grants in amounts proportional to the number of slaves owned previously, along the lines of the model used for the Banque de Martinique and the Banque de Guadeloupe.

As with the other colonial banks, this bank was a private institution, but it enjoyed the right to issue banknotes. And as of 1901, the bank became the Banque Internationale pour l’Afrique Occidentale, expanding its scope of activities to several other countries, including French Guinea, Ivory Coast, the Kingdom of Dahomey and French Congo.

Many years later, the BIAO would fall into the hands of the BNP.

And to this long list of colonial banks to which the French government granted extensive rights we could also add the Imperial Ottoman Bank, created by the Pereire brothers, two loyal supporters of Napoleon III, along with British investors. From 1863 to 1924, this institution performed the functions of a central bank under a protocol signed with the Ottoman authorities in Constantinople. Many years later the bank would end up in the hands of the Compagnie Financière de Paris et des Pays-Bas, now part of BNP Paribas.

Thus, this long history of French colonial banks resurfaces thanks to the revelations of The New York Times concerning Haiti – a long history in which the CIC was by no means the only player. While he is in no way responsible for these events that happened long ago, Nicolas Théry, the head of the Crédit Mutuel, decided in the wake of The New York Times disclosures to do everything possible to ensure that the truth is established and made known.

“As it is important to clarify all the components of the history of colonization, including in the 1870s, the bank will finance independent university research to shine a light on this past. As a cooperative and mutually-owned bank founded in 1882 to combat usury, the Crédit Mutuel has defended the values of liberty, equality and fraternity since its founding,” said the bank in a press release.

But as we have seen, the Crédit Mutuel is not the only bank involved in this history of colonial banks. BNP Paribas, the Crédit Agricole and the BPCE are implicated just as much. In any event, the community of historians has also been put on notice by these revelations which underscore the extent to which many obscured, dark areas continue to exist in the story of the economic history of French colonialism.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

Editing of the English version by Graham Tearse

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------