In our continuing investigations into the extraordinary espionage practices carried out by Swedish furniture retail giant Ikea targeting its employees, Mediapart has now obtained evidence that its management in France engaged in illegally obtaining personal information about customers who lodged minor complaints with its stores over faulty goods or delayed deliveries of their purchases.

The cases again include evidence that the company illegally sought personal data from French police files, and which could only be obtained by corrupting law enforcement officials with access to the information.

Earlier this month, Mediapart revealed how the managing director of Ikea France, Jean-Louis Baillot, along with the company’s head of Human Resources, Claire Hery, and its risk management director, Jean-François Paris, led an illegal and highly intrusive investigation targeting the company’s deputy director of communications and interior store planning, Virginie Paulin. The operation was mounted after they wrongly suspected that Paulin, who suffered from Hepatitis C, a debilitating liver disease, was fraudulently taking extended sick leave.

The case of Paulin was one of several involving spying on employees revealed by Mediapart and the French investigative weekly Le Canard Enchaîné. On March 1st, following a formal complaint launched by staff unions, the Versailles public prosecutor’s office launched a preliminary judicial investigation into the covert activities.

Ikea has temporarily suspended Paris, and following Mediapart’s revelations about the Paulin case, it last week suspended Baillot, head of the company’s French operations from 1996 to 2009 and now Ikea’s director for international commercial operations, and Hery, now manager of its store at Franconville. The company has also commissioned an internal investigation led by US law firm Skadden Arps.

The new evidence of how the furniture retailer set about gaining personal data of clients in dispute with its services department includes the case of a US-based Swedish couple who bought accessories for their newly-purchased holiday home in Brittany, western France. In November 2006, Hanna and Franck (whose names have been changed and last name withheld on their request) went to the Ikea branch at Evry, just south of Paris, to buy kitchen equipment and various accessories, including a bathroom basin and beds, paid and arranged for delivery on December 15th of that year.

The delivery finally arrived on February 8th, 2007, eight weeks after it was due. As a result Hanna and Franck had no other option but to live in Bed & Breakfast accommodation for the eight-week period and eat in restaurants. "All that cost us a lot of money," Hanna told Mediapart. "Our friends had bought air tickets. They lost them and were unable to get reimbursement."

Hanna wrote to Ikea to complain but was given no explanation. She persisted, calling a premium-rate number and complains of being passed from one person to another, having to explain her case to dozens of different people.

The couple wanted to obtain the reimbursement of their extra costs and apologies, both for themselves and their friends. "We have never been so badly treated by a business in all our lives," Hanna wrote in a formal letter she addressed to Ikea France.

The company’s services department replied on March 14th, expressing regret and offering to repay the couple’s costs, which Hanna calculated at 3,410 euros – 42 euros a night at the B&B and 20 euros a day in restaurants.

But the ensuing negotiations became bogged down. There were lengthy exchanges with services manager Youssra N’Gadi and also with Hakan Danielsson, deputy general manager in charge of finance, administration and security for Ikea France. It was only late in the summer of 2007 taht the couple eventually received a partial reimbursement of 1,619 euros.

The couple believed that was the sorry end to their story until Mediapart was able to inform her about an extraordinary investigation into their private mounted four years ago by Ikea France.

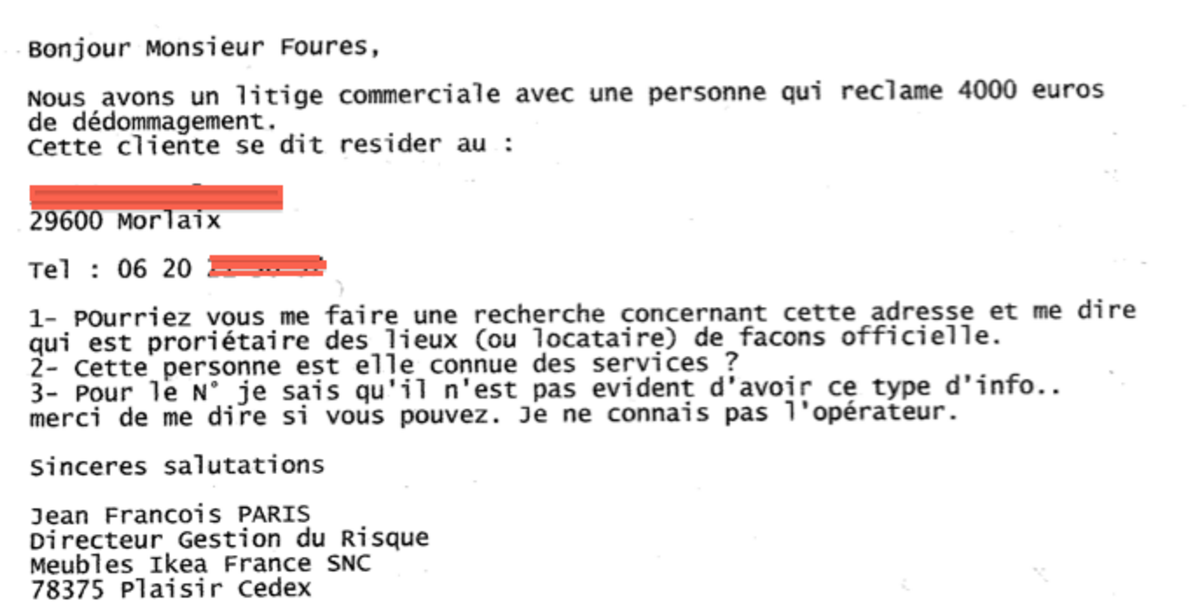

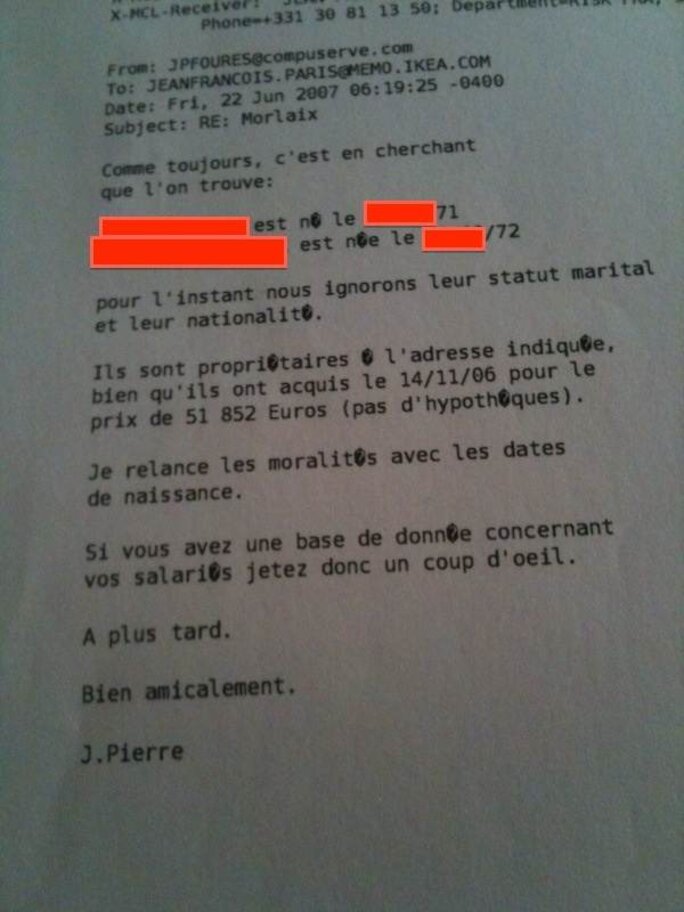

On June 6th, 2007 the Ikea France’s risk management director, Jean-François Paris sent an email (see immediately below) to a private detective, Jean-Pierre Fourès, who, since 2003, had been regularly employed by the company to investigate the past personal history of a number of Ikea employees.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

In the above email, Paris wrote to Fourès: "We have a business litigation with a person who is claiming 4,000 euros in compensation", and supplied the detective with Hanna’s Brittany address and mobile phone number, but not her name.

Paris asked Fourès to do three things, listed as follows:

"1 - Could you do checks on this address and tell me who the official owner is or who rents it?

2- Is this person known to [law enforcement] agencies?

3- For the number, I know it isn’t easy to get this kind of information… Thanks for letting me know if you can get it. I don’t know the [telecommunications] operator."

Checking customers' criminal records and 'morality'

The only way the detective could have been able to answer the second question, on whether Hanna was known to the police, would be to obtain confidential information from STIC, the French national police database, which holds data on people arrested for offenses as well as on victims of crimes. However, this is illegal and could therefore only be accomplished with the help of corrupt officials.

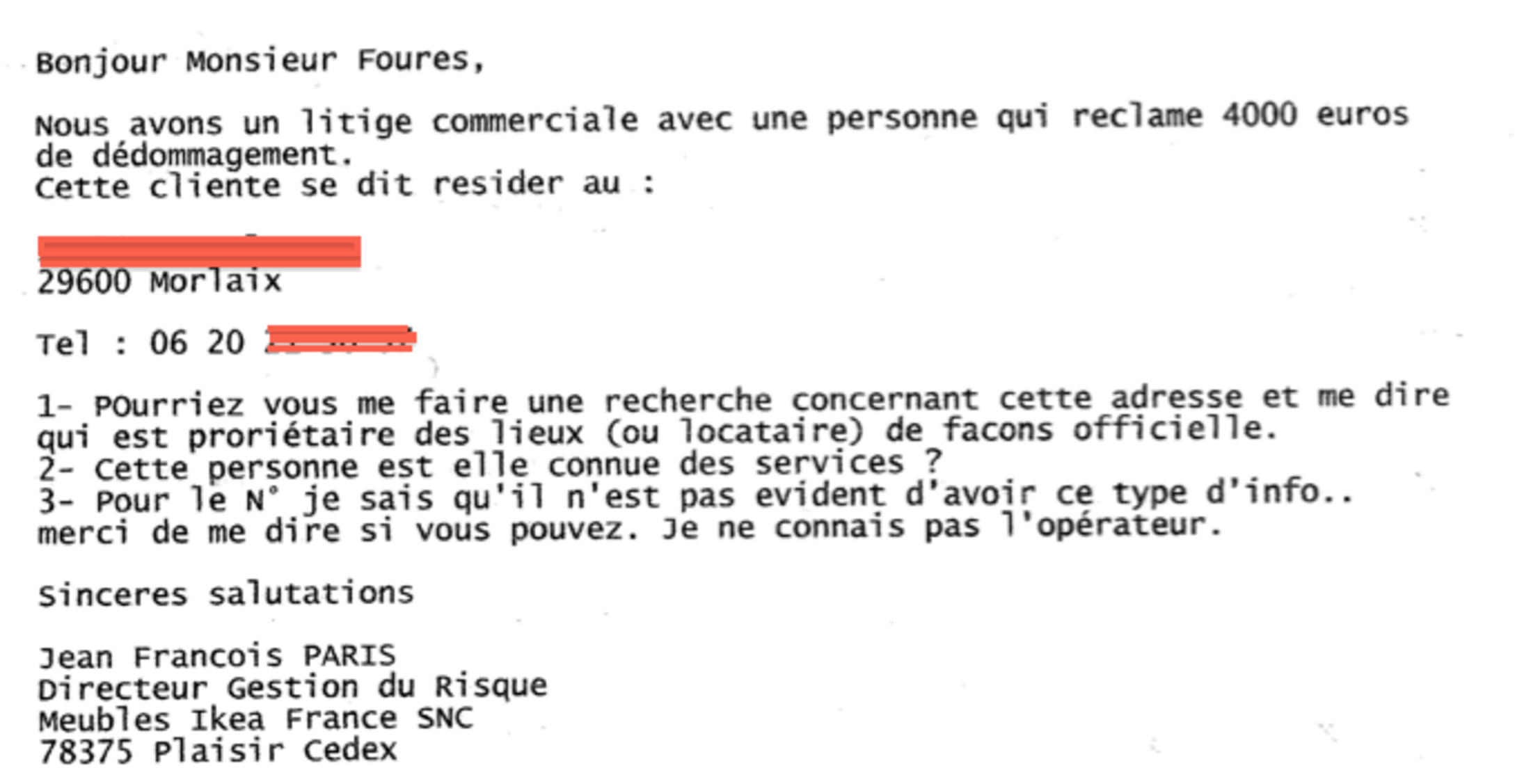

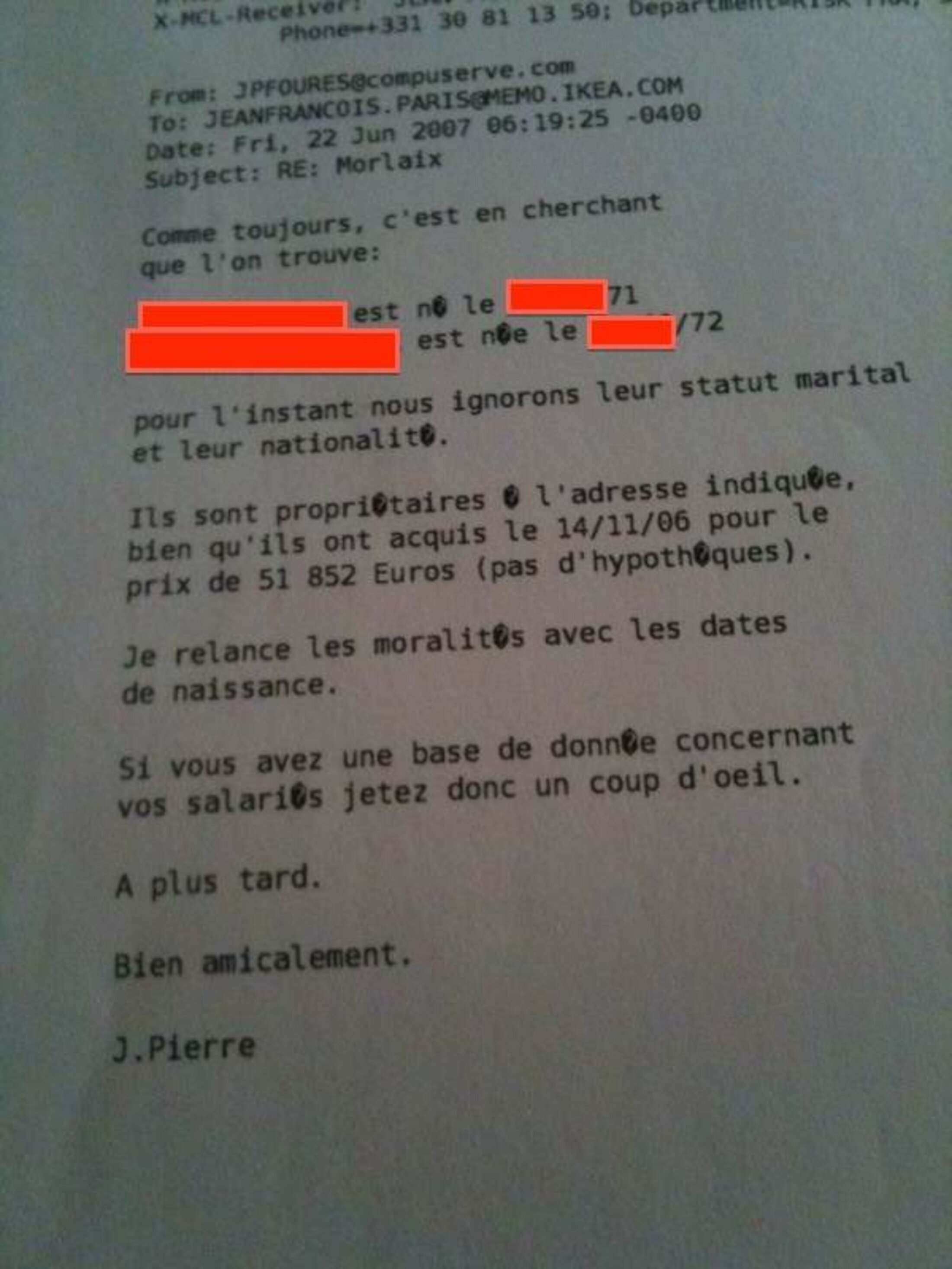

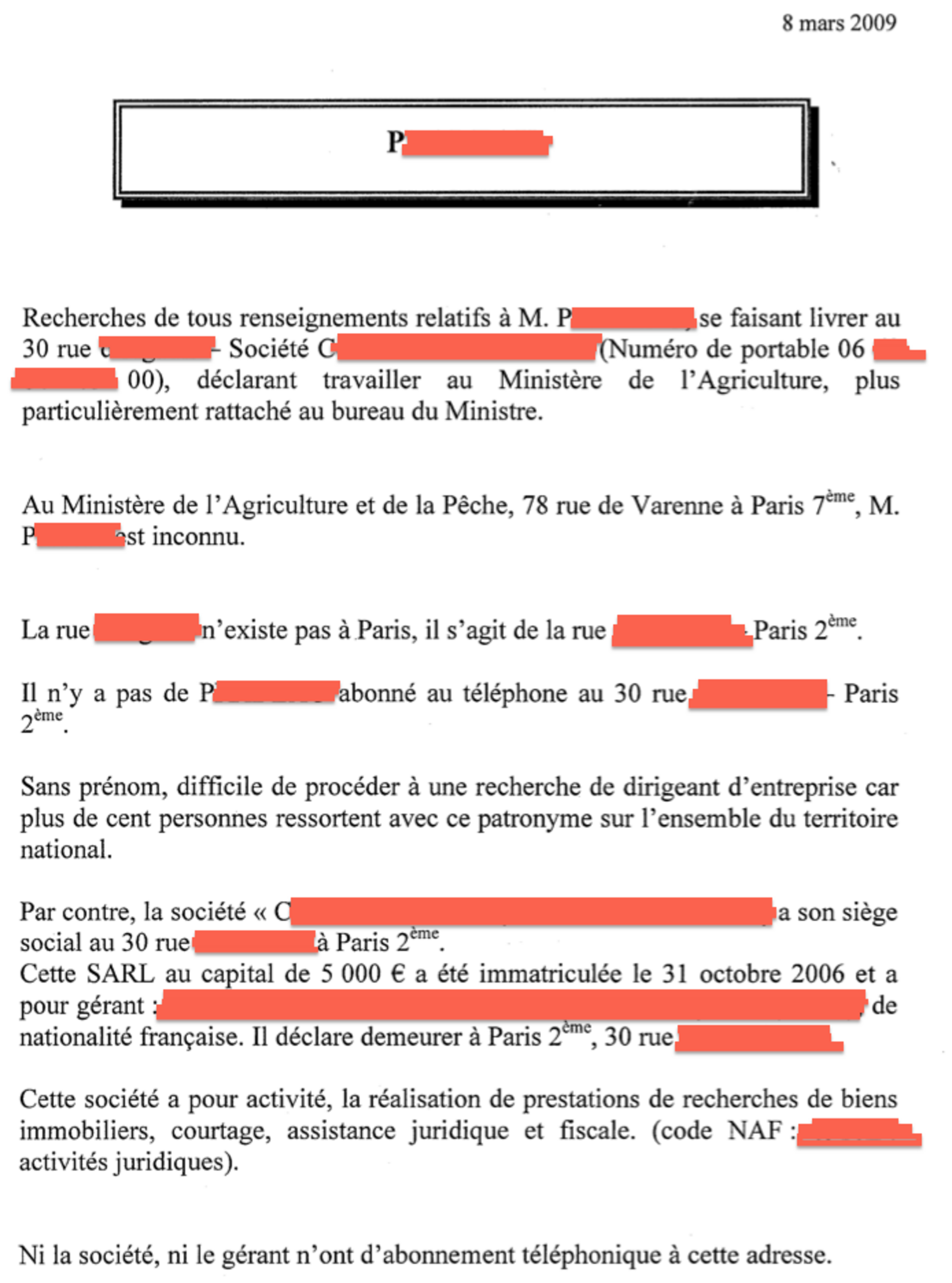

First Fourès sent (see below) what he called "a few preliminary elements" to Jean-François Paris and two other Ikea France managers – Danielsson, the deputy general manager, and Henri Dolivier, the head of client services.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

He confirmed the address and that the mobile phone number was Hanna’s. "At this address, the couple do not appear to be owners, so, by deduction, [are] renters." He added that queries about their "morality" were "underway".

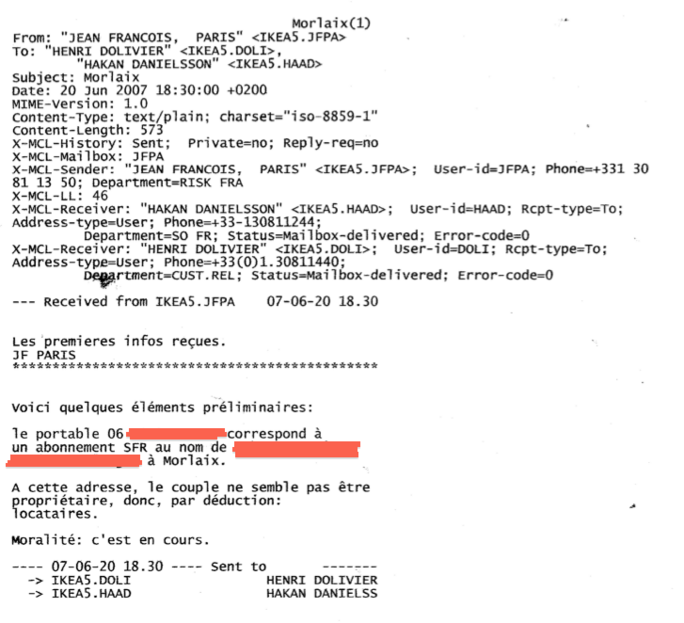

Two days later Fourès supplied more information. "As ever, if you look, you find" he announed."For the moment we do not know their marital status or nationality," he reported, but he had obtained Hanna and Franck’s dates of birth and consulted the land register. "They are owners at the address given, an asset they acquired on 14/11/06 for the sum of 51,852 euros (no mortgages)." Fourès promised "I will try again on morality with dates of birth."

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Hanna told Mediapart she now fears there might have been more emails revealing other personal details.

Another case of customer espionage uncovered by Mediapart targeted an estate agent who complained of being delivered faulty goods. Jérôme (last name withheld) bought a cupboard for his estate agency in Paris at the end of 2008 at the Ikea branch in Franconville, 20 km north-west of the city, which he said cost “about 200 euros". When it was delivered there was a problem with one of the wooden uprights. He called Ikea’s after sales service to ask that another be sent. Nothing happened. "I must have called them back three or four times, I wasn’t going to let it drop," he recalled.

That triggered an alert that went all the way to Ikea France headquarters and risk director Jean-François Paris, who decided that it was necessary to launch an investigation to obtain "all possible information relating to Monsieur P., whose delivery was to 30 rue X., (…) who said he worked at the Agriculture Ministry and in particular was attached to the minister’s office".

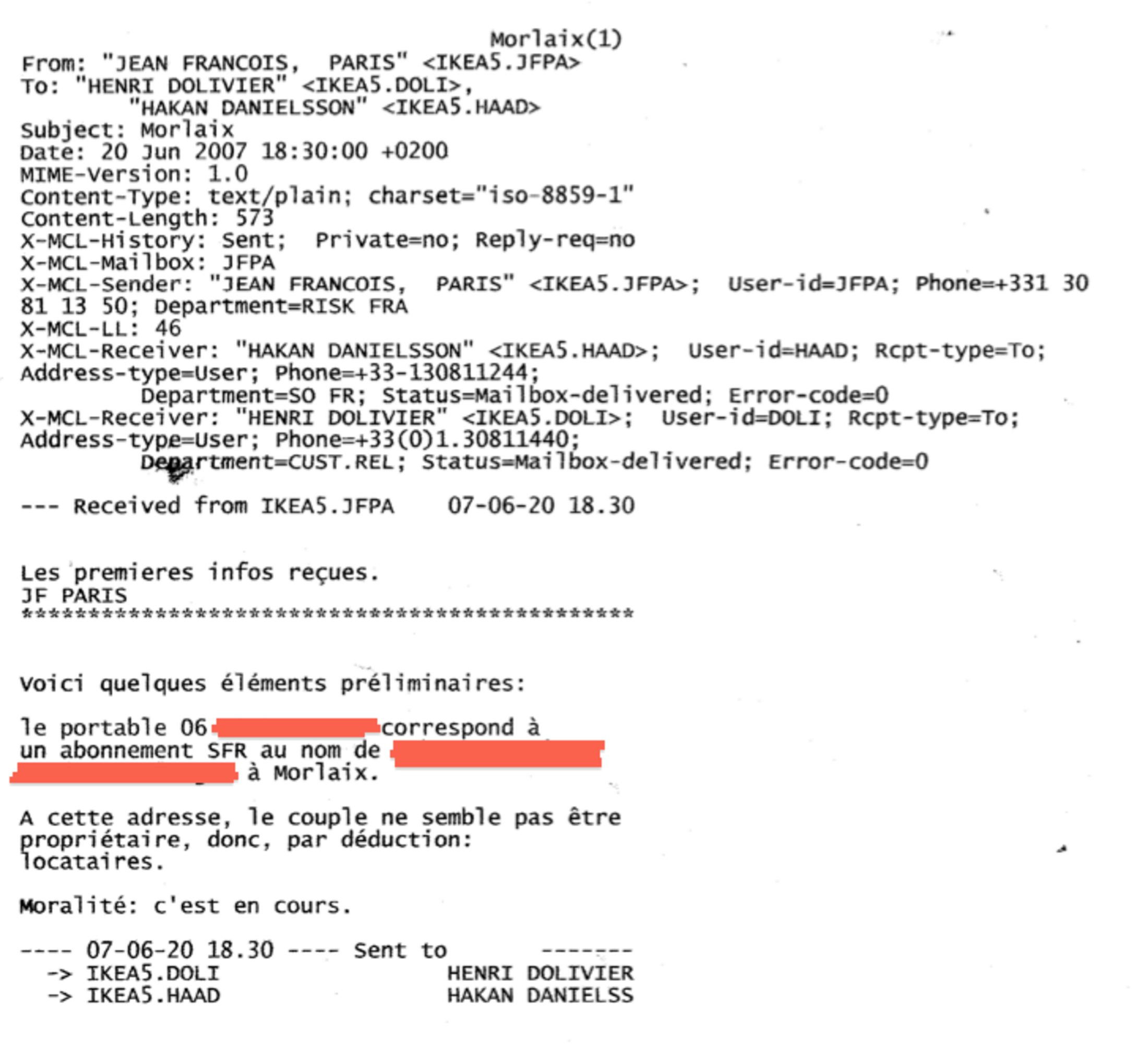

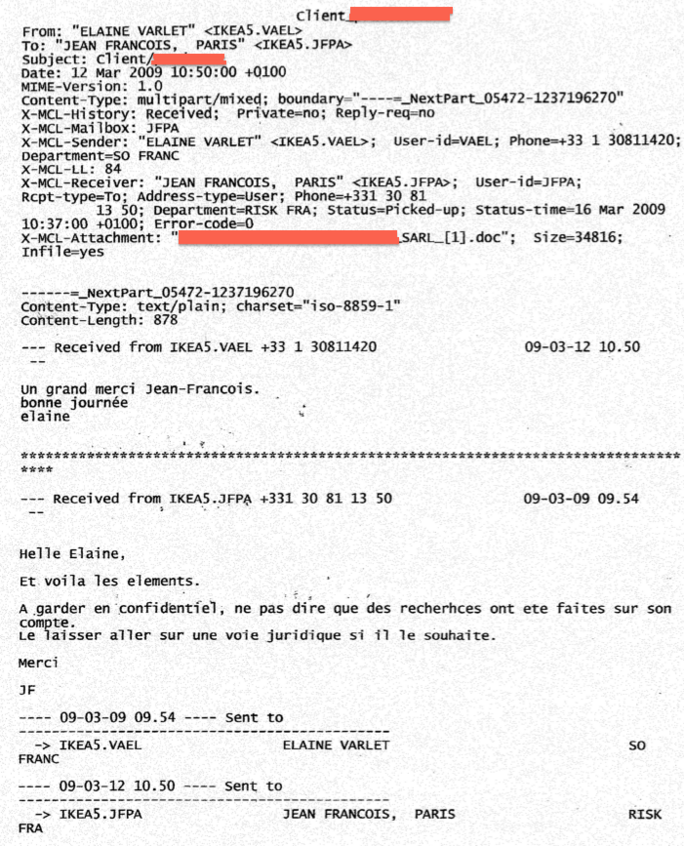

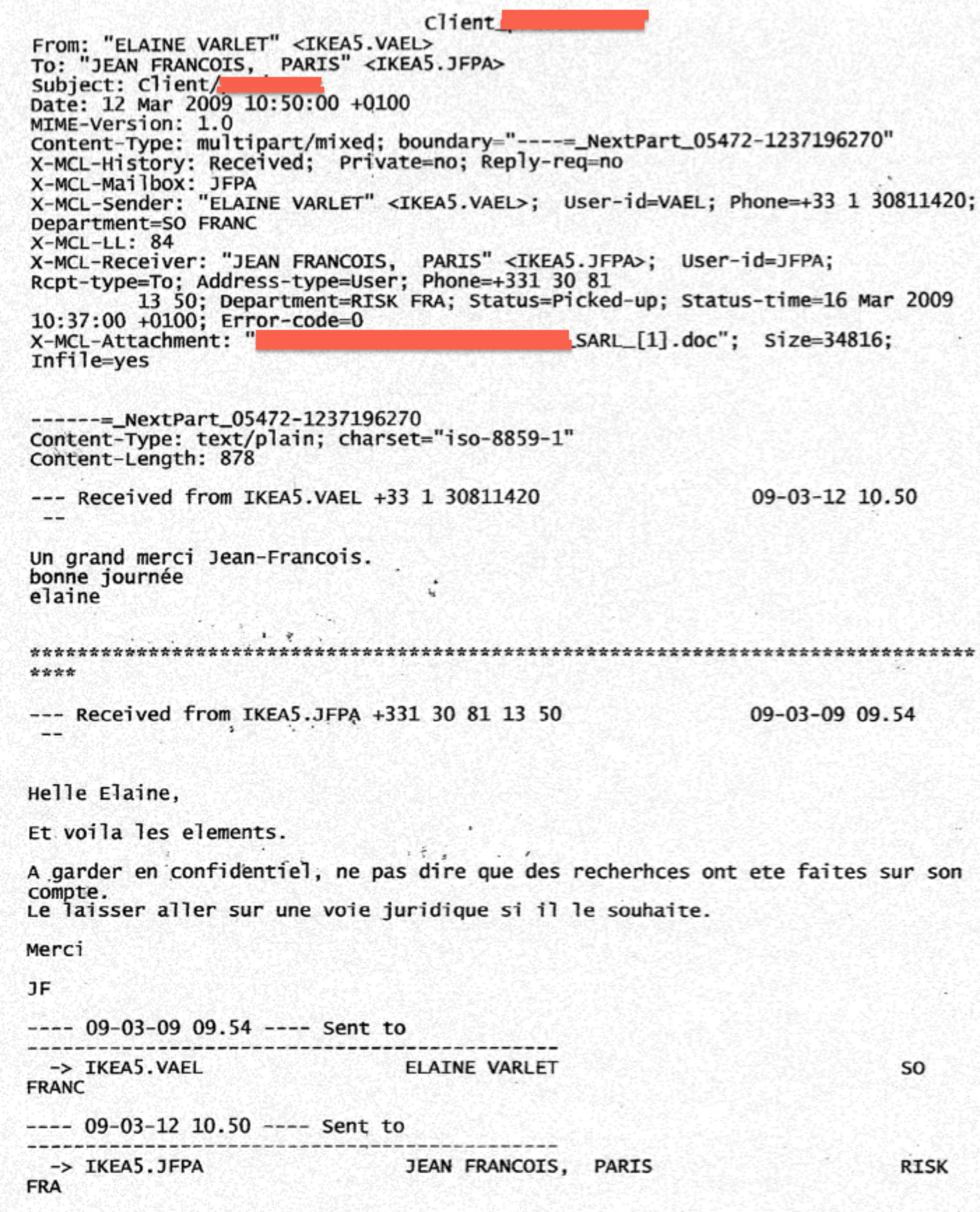

On March 9th 2009 Paris sent the data he received to a colleague at Ikea’s Franconville branch, Elaine Varlet (see email below), saying it was "to be kept confidential. Not to say that he had been investigated. Let him take the legal route if he wants to."

Enlargement : Illustration 4

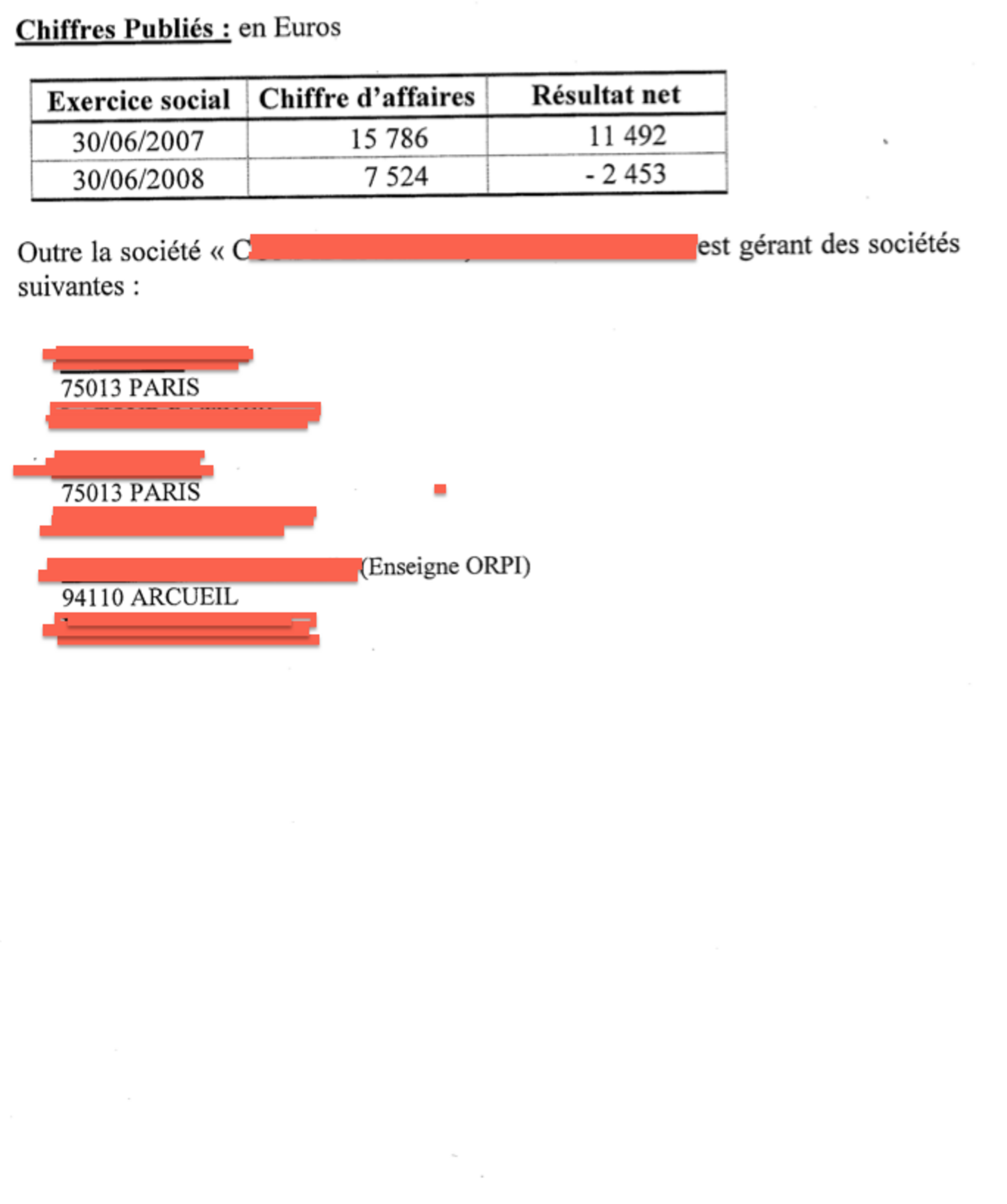

Fourès, the detective, found out little about Jérôme. He informed Paris that "Monsieur P. is not known at the Ministry of Agriculture and Fishing, 78 rue de Varenne, Paris 7th" and supplied corporate information on Jérôme’s estate agency, including turnover, net profit, the identity of its manager and his links with other companies.

Below is a copy of Fourès' email (left) and corporate info (right):

Enlargement : Illustration 5

Enlargement : Illustration 6

"It’s disturbing," commented Jérôme, who shops regularly at Ikea. "All that for a piece of furniture. The inquiry must have cost them more than my cupboard."

He said he was puzzled as to how the Agriculture Ministry came into the story. "I did what everyone does in those circumstances. I said I knew people in high places and that I would call the CEO if I didn’t get what I asked for," he said. "If it was about keeping tabs on people who don’t pay, but in this case, what is the point? What do they do with all the information?"

The bizarre spying of an ad salesman

Mediapart has also discovered a particularly bizarre case of spying by the furniture chain, which this time targeted an advertising salesman for the venerable review Le Journal du Parlement (‘The Journal of Parliament’). Founded in 1869, the publication is a magazine of reflection on political, economic and cultural issues, whose contributors include leading politicians, military figures and economists.

The 52 year-old salesman of Tunisian origin, whose identity is withheld here by Mediapart, contacted Ikea France’s communications department in November 2006 to interest the chain in placing an advertisement in the journal. “The operation went ahead in the most natural way, after I sent a dossier with the rates,” he told Mediapart. Agreement was reached and the review subsequently published a small advert.

"I must have got back to them a second time, without success,” he recalled. “It’s true that Le Journal du Parlement was not the ideal platform for Ikea.”

Mediapart can reveal that Ikea France risk management director Jean-François Paris commissioned private detective Jean-Pierre Fourèsto carry out an investigation into the salesman, but for what reason remains unclear. Fourès duly returned a three-page report, entiteled ‘Study’, addressed to Paris on November 29th 2006.

The report contained information about various companies the salesman had created since 1992, but also details about his marriage, 32 years ago in the Paris suburb of Sarcelles, to Véronique (last name withheld), including a note that the terms of their union were those of a “communal estate comprising only property acquired after marriage”.

-------------------------

English version: Sue Landau and Graham Tearse

(Editing by Graham Tearse)