Ian Brossat, the lead candidate for the French Communist Party in the European Parliament elections on May 26th, has one thing at least in common with Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, the president of Angela Merkel's party in Germany the CDU. And that is not just their firm opposition to French president Emmanuel Macron's plans to reform the European Union. For both want to see changes to the European Union's civil service.

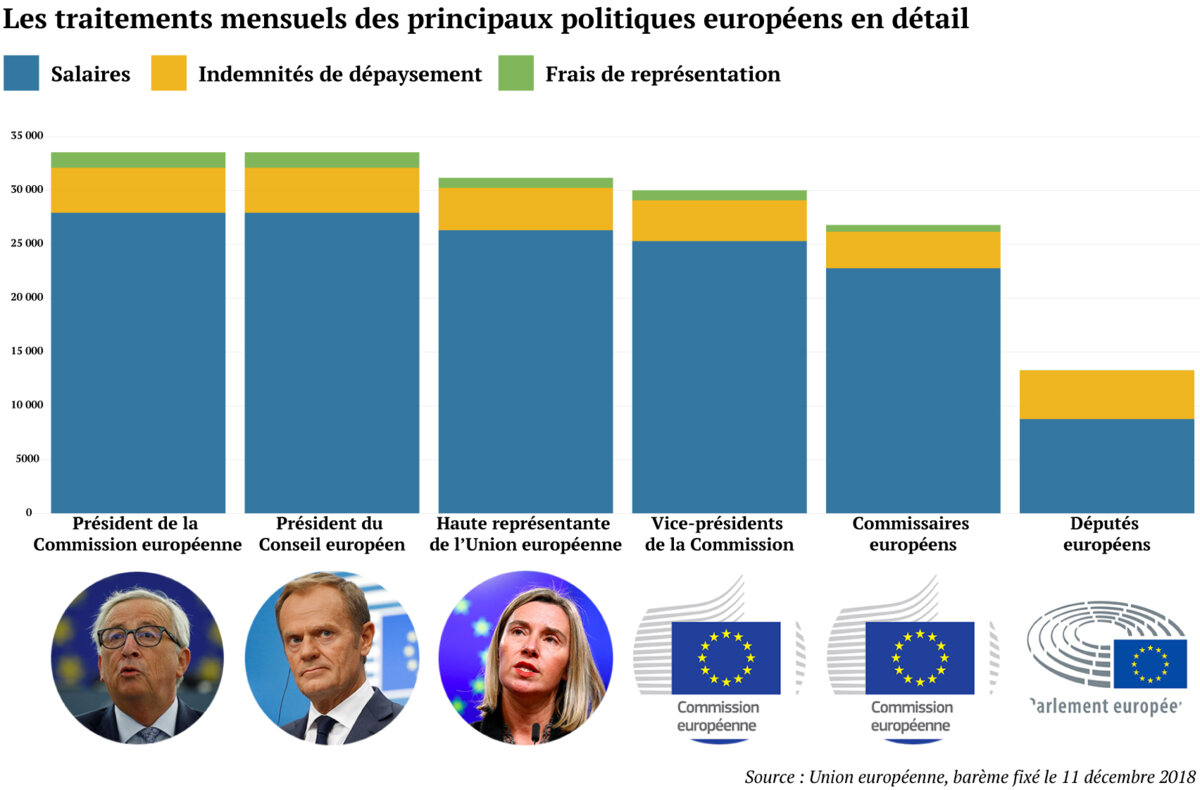

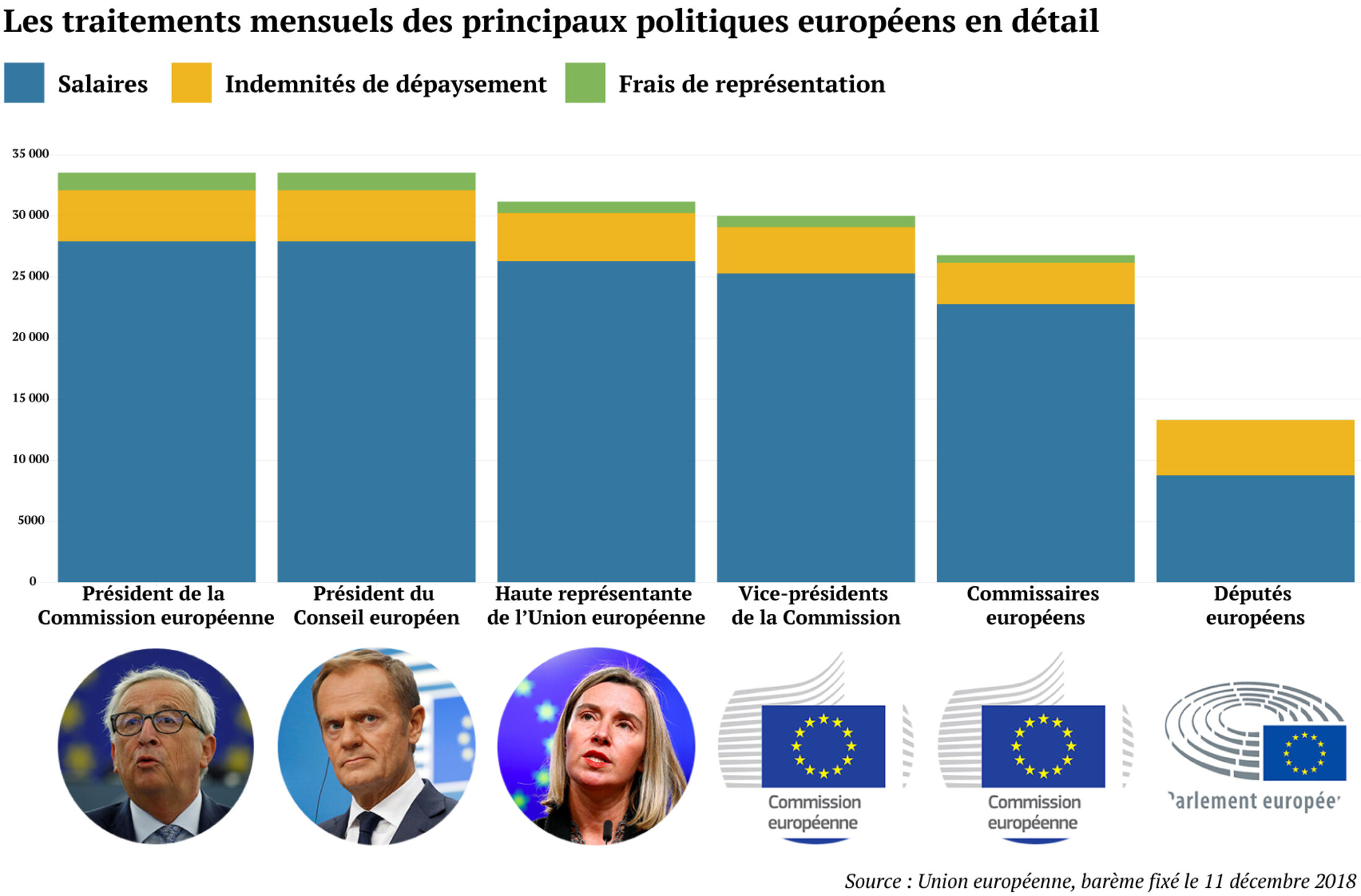

It was during a debate on April 4th between the lead French candidates for the European elections that Ian Brossat said he wanted to cut the Commission president's salary by two thirds. “Mr Juncker's salary must be reduced,” the assistant mayor at City Hall in Paris told the debate hosted by public broadcasters France 2 and France Inter. “Do you know how much the European Commission president is paid? He's paid 32,000 euros a month. That's double in one month what an average worker in Europe earns in a year. It's shameful.”

As for Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, or AKK as she is often known, in a response to President Macron's vision for the EU she made clear her desire to end some of the “anachronisms” inside the organisation, citing the example of EU civil servants not paying income tax.

Mediapart decided to take its own look at the benefits received by 'Eurocrats' at a time when inequality across the continent is growing and when the gap between citizens and their European institutions appears to be growing ever wider. And at first glance the figures are quite striking. For 2019 the EU has set aside 9.943 billion euros – some 6% of the total EU budget of 165.8 billion euros – to pay for, among other things, the salaries of around 60,000 officials. To put that into context, that figure is slightly more than the total number of public sector workers employed by Paris city council.

The figures also support Ian Brossat's arguments about the levels of pay at the top; the 28 European commissioners, for example, earn very high salaries. And the Commission president's monthly gross pay is 138% of that received by the various director generals, the highest rung of the EU civil service. That means they get 27,903.32 euros gross a month even if 45% of this is deducted at source and is ploughed back into the EU's coffers.

Meanwhile Jean-Claude Juncker also gets a 4,185.50 euros a month housing allowance (that's 15% of his gross salary) plus a further 1,418.07 euros for monthly entertainment expenses. That comes to a monthly total of 33,506.86 euros a month for the Commission president. The president of the European Council, Donald Tusk, is on a similar package.

The other members of the Commission do not miss out either. Federica Mogherini, the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, receives a total of 31,731.63 euros a month between her gross salary and her various expenses and allowances. And the monthly gross salary and allowances for the Commission's vice presidents comes to 29,977.34 euros a month each.

The other commissioners, including France's Pierre Moscovici, who is in charge of economic affairs and taxation, are not far behind, receiving a total of 27,070.75 a month in gross pay and allowances.

As for the Members of the European Parliament or MEPs, they get a monthly salary of 8,757.70 euros gross (6,824.85 net) plus a general expenses allowance of 4,513 euros a month. These expenses are supposed to cover their costs as an MEP for transport, communications and renting an office in their constituency. But there is still very little control over how these allowances are spent in practice.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Meanwhile the EU civil servants, who are mostly based in Brussels or Luxembourg, also get significant pay and allowances.

According to the latest salary tables the Commission's senior civil servants (of whom there are around 12,000) receive monthly pay ranging from 4,787.36 to 20,219.80 euros a month gross. Just under 5,000 of them earn gross monthly pay of more than 10,000 euros. A 2013 report by the French Parliament's upper chamber, the Senate, estimated that the average monthly salary for EU civil servants was around 6,500 euros net.

Like the commissioners, if a civil servant is not living in their own country they get an out-of-country or expatriate allowance which is worth 16% of their salary. This is a benefit they keep throughout their careers in the EU institutions. They also get an bonus when they first join, which is worth two months' salary. EU civil servants also have their own system for social security and family benefits.

Yet while these figures are striking, they are in line with other international organisations. Indeed, the EU's predecessor, the old European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), which dates from the 1950s, had established a policy of generous pay for its first recruits.

In their book La Fonction publique européenne en perspective ('The European Civil Service in Perspective'), authors and EU officials Jean-Luc Feugier and Marie-Hélène Pradines say these salaries were deliberately aligned with the “pay levels of senior managers employed in the steel and mining industries, [sectors] that were particularly profitable at the time”. The intention was apparently to tempt engineers, economists, interpreters and lawyers to join this new project aimed at rebuilding Europe. And this meant living in Belgium or Luxembourg.

Decades later the ECSC became the EU and this tradition of comfortable salaries has continued. The argument in favour is always the same: that the salaries inside the institutions, the Court of Justice, the European Central Bank (which has its own pay scale) and the 30 agencies linked to the Commission, want to be as attractive as possible to the best European minds.

It is, meanwhile, wrong to say, as Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer and others claim, that European civil servants do not pay income tax. While it is the case they do not pay the tax in the country where they work – Belgium or Luxembourg in most cases - they do pay a European income tax, on top of local taxes. This EU income tax is a progressive tax with 14 different bands – with tax rates going from 8% to 45% - and is deducted at source. On top of this there is a 'solidarity' deduction of 6%. In 2019 this income tax is set to raise 1.6 billion euros for the EU budget.

Expatriate bonuses for 20 years?

Moreover, not paying income tax in your country of residence is not just the privilege of European bureaucrats. It is an old tradition that goes back to the League of Nations, forerunner of the United Nations, whose international staff were exempted from income tax.

The EU income tax rate is low by Belgian standards. If the top EU civil servants had to pay income tax in Belgium, where the Commission is based, they would all face an income tax rate of 50% in a country with one of the highest tax rates in the EU. But as a trade union source points out, unlike national tax systems, EU income tax does not have any allowances or tax breaks, for example for people with mortgages.

Unsurprisingly the dozen or so officials, Parliamentary assistants and other staff who spoke to Mediapart on condition of anonymity found it difficult to talk about their pay and allowances. Many of them also think that a focus on their pay helps feed what they see as simplistic criticism of the European institutions

The staff point out that their salaries were frozen between 2011 and 2014, years of economic crisis, and say that over the same period the European institutions reduced their overall salary bill by 5%. Others note that their salaries and allowances are fixed by the EU member states and that pay grades and benefits are made public.

Many of them are at pains to say they think their salaries are justified. The European civil service, say staff, is full of responsible positions that attract people who speak many languages, have many qualifications and are specialists in what are sometimes very specialised domains, for example competition law or environmental law. These are the people who work on EU directives, prepare the groundwork for commercial negotiations, investigate the mergers of large companies or who check that EU aid money is being properly distributed.

Another argument advanced by officials in support of their comfortable salaries is the need to avoid the revolving door syndrome in which staff walk out of their EU job and straight into a well-paid job with a legal practice or a lobby firm. But this argument falls down a little as the revolving door syndrome is already widespread practice among many commissioners, MEPs and officials, who take up new employment as soon as they leave their position.

“It's more or less the same salary that you can get at the [French Finance Ministry] or the Ministry of Ecological Transition and Solidarity,” says one official familiar with the recruitment policy in EU institutions, playing down the level of pay. Another official, who has worked in the German civil service, shares this view.

But there are some bizarre aspects of the Eurocracy which are harder to understand. For example, while one can justify an expatriate bonus when a civil servant and their family have to move abroad, is it right that they get this bonus of 16% their salary for ten or 20 years? Many of the officials make an entire career out of working for the EU's institutions. But if they are not Belgian or from Luxembourg, are they still expats if they buy a home in Brussels and bring up a family there? “I always consider myself to be an expat,” one EU civil servants says.

“I hope that your article will also talk about diplomats from member states in post in Brussels, and NATO personnel,” a Commission spokesperson, Alexander Winterstein, told Mediapart. Brussels, which on top of being the capital of Belgium and home to the EU is also the headquarters for NATO, is something of a one-off in Europe. Its population is 1.2 million but close to six in every ten inhabitants do not come from the country. The Brussels Institute for Statistics and Analysis (BISA) estimates that around 48,000 European officials and diplomats live in the Belgian capital.

No study has been carried out on how much Brussels misses out in terms of income tax revenue from its international workers. But both the city's regional authorities and the European Commission believe that the overall impact of the European institutions is a beneficial one. According to a study by the Office of the Brussels Commissioner for Europe and International Organisations, the presence of the various international institutions represents around 120,000 jobs in the Brussels area and brings in around five billion euros a year in VAT revenue, mostly via hotels and restaurants.

But there is a striking contrast between a European organisation with very well-paid staff and the inhabitants of the Brussels region where the public authorities are struggling to bring down levels of unemployment and poverty (see Mediapart's report, in French, on growing poverty in Brussels here). Many diplomats, Eurocrats and other lobbyists have very little contact with the rest of the population and live in their own precisely-defined areas.

“The question needs to be raised as to the contribution made by international institutions in the cities where they are based,” says Marc Botenga, lead candidate in the European elections for the radical left Workers' Party of Belgium or PTB and political advisor to the left-wing European United Left/Nordic Green Left grouping at the European Parliament. He believes that the Belgian authorities could renegotiate the financial contributions made by the city's many international institutions. “Brussels is a European capital but does that mean that the people of Brussels live better? That Belgians live better?” he asks.

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter