Video evidence that warships built and sold by France to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) have played an active role in the maritime blockade of Yemen, which has contributed to what the UN has described as the worst humanitarian crisis in the world, has emerged in an investigation partnered by Mediapart.

The video footage, published here for the first time in public, mounts further pressure on the French government to take action over its exports of arms to belligerents in the Yemeni war. It has repeatedly claimed to have no knowledge of use made of the weapons, despite revelations published earlier this year by Mediapart and its online partner Disclose which provided documented evidence of their deployment on the frontline.

Meanwhile, the conflict escalated at the weekend after an aerial attack by drones on a Saudi oil-processing facility at Abqaiq and an oilfield, at Khurais, which Iran-aligned Houthi rebels in Yemen claimed responsibility for. US officials have said the Saturday bombings, which cut worldwide oil supplies by around 5%, was carried out by Iran, which has denied the claim.

The crisis in Yemen, situated at the far south of the Arabian Peninsula and which shares a common border with Saudi Arabia, began in earnest after the rebel Houthi movement from Yemen’s Shia Muslim minority, supported by Iran, took control of a large swathe of the west of the country in early 2015, causing President Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi to flee to Saudi Arabia, his ally.

To restore the UN-recognised Hadi regime’s control of the country, Saudi Arabia formed a coalition with the UAE and eight other majority Sunni Muslim Arab states which launched – with the backing of the US, Britain and France – a series of attacks by air and sea against Houthi targets in Yemen, beginning on March 26th 2015. Since then, the Saudi-led coalition – now made up of Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Sudan and Bahrain – has continued to wage war on the Houthis by air, land and sea.

The Saudi-led coalition has notably employed a strategy of starving the population with attacks on farms and food supplies within the Houthi-controlled western region in Yemen, although food shortages also affect other areas. Meanwhile, Houthi forces themselves have been accused by the UN of hi-jacking humanitarian aid destined for civilians. The UN says 80% of Yemen’s population of just more than 28 million are in need of humanitarian assistance, of which at least 8.4 million are at immediate risk of starvation, amid widespread malnutrition and notably among children. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that more than 1.1 million people are infected with cholera, which has already killed several thousand.

One of the key causes of the humanitarian crisis is the maritime blockade by the Saudi-led coalition, and notably the Houthi-held Red Sea port of Hodeida, through which passes most food and medical aid supplies for the Yemeni population, and also fuel and general freight. The justification given for the blockade and interception of vessels is to prevent arms shipments reaching the Houthis. A UN Security Council Resolution, 2417, adopted on May 24th 2018, stated that, “[The UN] Strongly condemns the unlawful denial of humanitarian access and depriving civilians of objects indispensable to their survival, including wilfully impeding relief supply and access for responses to conflict‑induced food insecurity in situations of armed conflict, which may constitute a violation of international humanitarian law.”

Enlargement : Illustration 1

French Arms, an investigation initiated by Dutch collaborative media organisation Lighthouse Reports, in cooperation with French online investigative magazine Disclose and with the involvement of Mediapart, TV channel Arte, Radio France and Bellingcat, has collected video evidence that warships sold by France took part in the Saudi-led coalition’s maritime blockade.

The vessels include the UAE’s missile-launching corvette Al Dhafra, which in October 2015 intercepted an Indian cargo ship heading for Yemen through the Bab-el-Mandeb strait, a key shipping route situated between the southern Arabian Peninsula and the Horn of Africa.

Two other French-built warships belonging to the Royal Saudi Arabian Navy, the frigates Al Dammam 816 and Al-Madinah 702, were caught on camera in 2017 proceeding with an inspection of an oil tanker close to the port of Hodeida.

In parallel with a land and sea blockade, the coalition mounted a total blockade of Yemeni ports in November 2017, which was partially lifted several weeks later in face of international alarm over the drying up of urgent relief supplies for Yemen’s starving population. In the meantime, some perishable cargo had become unfit for distribution. A report by the UN office of the High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) published in August 2018 concluded the ongoing maritime blockade “has denied entry to vessels on a seemingly arbitrary basis”.

In an interview with French news channel BFM-TV on October 30th 2018, French defence minister Florence Parly described the situation in Yemen as “a humanitarian crisis the likes of which have never been seen before,” adding: “It is a priority for France that humanitarian aid can get through.” Yet the warships built and sold by France to its Gulf state allies were contributing to that very crisis.

In December 2017 Sébastien Nadot, a Member of Parliament (MP) from President Emmanuel Macron’s LREM party, submitted a written question to the French government in which, underlining the heightening by the blockades of the humanitarian crisis in Yemen, he asked what action France intended taking. In its reply in February 2018, the foreign affairs ministry said that in discussions with Saudi’s King Salman on December 24th 2017, President Macron had “made known his strong preoccupation regarding the humanitarian catastrophe in the Yemen” and had called on the king to “entirely lift the blockade to allow humanitarian aid and commercials goods to enter Yemen”.

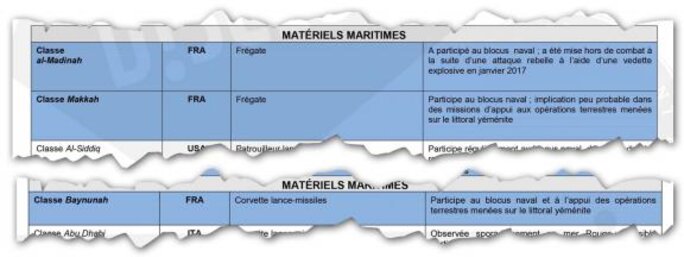

Both Emmanuel Macron and Florence Parly were fully aware of the participation of the French-made warships in the blockade, as confirmed in a report by Disclose and published by Mediapart in April this year. That report revealed a confidential 15-page document, obtained by Disclose, which was prepared by France’s military intelligence agency, the DRM. Dated September 25th 2018, the DRM document detailed the deployment of French-made weaponry by the Saudi-led coalition, in the air and on land, and also the role of two French-built warships which it said “take part in the naval blockade”.

The DRM report was submitted to Emmanuel Macron and Florence Parly and then presented before a defence council meeting on the war in Yemen that was held at the presidential office, the Élysée Palace, on October 3rd 2018 – three weeks before Parly’s interview, cited above, with BFM-TV.

The revelations this April of the existence of the DRM report produced no official reaction, other than the summoning for questioning by the French domestic intelligence agency, the DGSI, of journalists from Disclose (see more here).

However, the reports did contribute to wider public debate over the continuing supply of French weapons to the Saudi-led coalition; in early May, several French and Belgian NGOs, together with dockers’ unions, mounted an operation to block the loading of weapons on a Saudi ship in the northern port of le Havre. That was followed by a similar operation led by the dockers’ branch of the CGT union in the southern port of Fos-sur-Mer, close to Marseille. “We will never load arms destined to kill civilians,” said CGT union official Laurent Pastor in an interview with public broadcaster France 3. The union also issued a statement saying, “Faithful to our history and values of peace, our union stands against all wars across the globe. We combat imperialism, the destabilization of certain countries, against the pillaging of primary resources, against all geopolitical wars”.

In the DRM report, it was noted that a UAE warship, which was not named but was identified as being of the Baynunah-class – the same as the corvette Al-Dhafra, identified in the video – took part in the maritime blockade. The ship was built by the Cherbourg-based French company Constructions mécaniques de Normandie (CMN) which is owned by French-Lebanese billionaire Iskandar Safa (who also owns the rightwing French weekly magazine Valeurs actuelles).

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Up until 2016, CMN sold six Baynunah-class corvettes to the UAE as part of an order that was placed in 2003, which the company said was worth a total of 675 million euros. The first of the six corvettes was built in Cherbourg, while the five others were built in the UAE by the Abu Dhabi Ship Building company (ADSB) under the supervision of CMN. One of these was the Al-Dhafra, which entered service in 2013. It is equipped with French weaponry that includes Exocet ship-to-ship missiles (supplied by French company MBDA) and an AS565 Panther military helicopter (built by Airbus Helicopters, formerly Eurocopter). None of the companies replied to questions on the use of the corvette in the maritime blockade which were submitted to them during the preparation of this report.

The two other warships presented in the videos – the Saudi frigates Al-Madinah 702 and Al-Dammam 816 – were built by the Naval Group (formerly the DCNS), in which the French state has a 62.5% stake, at its shipyards in Lorient, north-west France.

'Starvation may have been used as warfare': UN

The frigate Al-Madinah 702 was delivered to Saudi Arabia in 1985, as part of an arms contract called Sawari I which was signed with France in 1980. The Al-Dammam 816 was delivered as part of a second arms contract between France and Saudi Arabia, called Sawari II, and entered service in 2004.

The Sawari II contract is at the centre of a political scandal in France over evidence that funds were secretly syphoned off from the deal to finance the 1995 presidential election campaign of former French prime minister Édouard Balladur. Placed under investigation in 2017 for complicity in the embezzlement of public funds, Balladur, now aged 90, faces a possible trial before the French court dedicated to investigating and trying members of government suspected of wrongdoing while in office, the Cour de justice de la République (CJR).

Naval Group continues to work with Saudi Arabia, notably for the renovation and modernisation of the country’s warships, and this despite the maritime blockade of Yemen, as Mediapart reported in March this year. An engineer from the company, interviewed by Mediapart in that report, recounted his stay in the Saudi Red Sea port of Jeddah, where he was assigned to work on frigates: “It's a strange life,” he recalled. “You divide your time between a luxurious compound with a pool, traffic jams and working on the dockyard where you renovate warships.” Other French sub-contractors are also involved in the maintenance of Saudi warships.

In the case of French warships sold to the UAE, defence and aerospace group Thalès and the CMN carry out maintenance work on the vessels (Thalès widened the scope of its contract for this with Abu Dhabi Ship Building in 2015). Questioned, neither company would confirm or deny whether the Baynunah-class frigates are included in their maintenance work.

Questioned by Mediapart, the Council of French Defence Industries, CIDEF, which represents France’s principal weapons manufacturers, provided a statement (click here, or on the "More" tab top of page to see the text in full) in which it said: “No sale of systems is carried out without a prior authorisation delivered by an inter-ministerial commission under the auspices of the Prime Minister and presided by the Secretary General of Defence and National Security.”

Enlargement : Illustration 5

The emergence of the video evidence that warships built and maintained by French companies directly participate in the blockade of Yemen comes just two weeks after the publication by the UN Human Rights Council of a damning report into rights abuses in the Yemen conflict. The report was prepared by a panel of experts, the “Group of Eminent International and Regional Experts on Yemen”, appointed by the UN in 2017.

The panel is chaired by Kamel Jendoubi, a Tunisian rights activist and former minister, and also includes Charles Garraway, who served for 30 years in the British army’s legal services as a criminal prosecutor and adviser in the law of armed conflict and operational law, and former Australian minister and MP Melissa Parke, who was for eight years a senior lawyer for the UN.

In their report, the experts said there were “justified deep concerns that starvation may have been used as a method of warfare by all parties to the conflict. Such deprivation also amounts to prohibited inhuman treatment. Considered serious violations of international humanitarian law, these acts may lead to criminal responsibility for war crimes”.

Presenting the report released on September 3rd, the UN Council said it “details a host of possible war crimes committed by various parties to the conflict over the past five years, including through airstrikes, indiscriminate shelling, snipers, landmines, as well as arbitrary killings and detention, torture, sexual and gender-based violence, and the impeding of access to humanitarian aid in the midst of the worst humanitarian crisis in the world”.

The experts, added the UN rights council, “found that the governments of Yemen and the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, as well as the Houthis and affiliated popular committees have enjoyed a “pervasive lack of accountability” for violations of international humanitarian and human rights law”.

“Five years into the conflict, violations against Yemeni civilians continue unabated, with total disregard for the plight of the people and a lack of international action to hold parties to the conflict accountable,” said Jendoubi. “The international community must stop turning a blind eye to these violations and the intolerable humanitarian situation.”

The experts’ report underlined the role of “Third States” which, they wrote, “have a specific influence on the parties to the conflict in Yemen […] including by means of intelligence and logistic support, as well as arms transfers. Such is the case of France, the Islamic Republic of Iran, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the United States of America, among other States.”

“States may be held responsible for providing aid or assistance for the commission of international law violations if the conditions for complicity are fulfilled,” the panel warned. “States are obliged to take all reasonable measures to ensure respect for international humanitarian law by other States. Furthermore, the Arms Trade Treaty, to which France and the United Kingdom are parties, prohibits the authorization of arms transfers with the knowledge that these would be used to commit war crimes. The legality of arms transfers by France, the United Kingdom, the United States and other States remains questionable […] The Group of Experts observes that the continued supply of weapons to parties involved in the conflict in Yemen perpetuates the conflict and the suffering of the population.”

The 2013 Arms Trade Treaty, which France signed up to in 2014, and to which, according to the French foreign affairs ministry, it “attaches the greatest importance”, states that: “Transfers of arms, ammunition/munitions and parts and components are also prohibited if the State Party has knowledge at the time of authorization that the arms or items would be used in the commission of genocide, crimes against humanity, grave breaches of the four Geneva Conventions, attacks directed against civilian objects or civilians protected as such, or other war crimes as defined by international agreements to which it is a Party.”

Enlargement : Illustration 6

Contacted by Mediapart, the French prime minister’s office (click here, or on the "More" tab top of page to see the text of the statement in full) said “France exercises a strict, transparent and responsible control of exportations of war equipment”, and that “the question of the conditions of use of arms is examined at the time of the request for authorisation, ahead of the delivery of the licence”.

“The authorisation is granted according to the information available at the time of this examination,” it insisted, adding: “If the conditions of use, as envisaged at the time of the granting of authorisation, evolve, France then endeavours to transmit adequate messages and to act in every manner possible to lead to a de-escalation.”

That, according to defence minister Florence Parly herself, is an approach that has little chance of success. On May 7th this year, Parly told the defence commission of the French parliament’s lower house, the National Assembly, that it was “obviously very complicated” to “control” the use of military equipment once it had been supplied. “On the one hand because it is very difficult to place a control manager behind each piece of equipment we sell,” she told the commission. “And, on the other hand, what would be the probability that the sovereign country whicht had bought this equipment would accept such a control? Selling military equipment while imposing from the outset acceptance of the limitation of its usage would be a quite difficult transaction to negotiate, and I do not know of states which accept such a limitation of sovereignty.”

Despite repeated demands by NGOs that France puts a stop to its arms exports to Saudi Arabia, the government appears steadfast in its refusal to interrupt the trade with its diplomatic ally and indispensable economic partner. As Mediapart reported in January (in French, here), Naval Group, with the support of the government, is seeking to conclude a deal with Riyadh for the sale of five more corvettes. In February, the group Saudi Arabian Military Industries, owned by a Saudi sovereign fund, announced on Twitter the signing of a “strategic agreement” with Naval Group for the creation of a joint company.

At this same period, French foreign minister Jean-Yves Le Drian, who served as defence minister under the 2012-2017 presidency of François Hollande, lied to the foreign affairs commission of the National Assembly when he claimed, on February 13th, that in the Yemen conflict, “Action by Saudi Arabia is essentially carried out by air”, adding: “We supply nothing to the Saudi air force.”

Le Drian did not tell the MPs that France had in fact sold military equipment to the Saudi air force since the beginning of the conflict in Yemen, and he failed to tell the commission that the Saudi-led coalition’s offensive against the civilian population was also led on land and at sea.

Even the international diplomatic tensions surrounding Saudi Arabia following the murder in its consulate in Istanbul on October 2nd 2018 of Saudi dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi prompted no change in France’s position regarding its weapons sales to Riyadh. “What is the connection between arms sales and Jamal Khashoggi?” asked President Emmanuel Macron in response to a question put to him at a press conference during a visit to the Slovakian capital Bratislava on October 26th. “I understand the connection with Yemen but there is none with Jamal Khashoggi. If one wants to impose sanctions, they should be taken in every area. In that case the sale of vehicles should stop.” Germany, meanwhile, decided shortly after Khashoggi’s murder to halt weapons sales to Saudi Arabia, a move that also blocked the sales by other countries, like Britain and France, of weapons in which German-supplied components were fitted.

In 2018, Saudi Arabia was the third biggest export market for French weapons, with deals totalling almost 1 billion euros.

-------------------------

- The French version of this report can be found here.

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

English version by Graham Tearse