Michel A. was one of the first French volunteers, indeed possibly the first, to go and fight against the Soviet invaders in Afghanistan. In November 1985 when we met him he had just arrived in Miranshah, the small capital of North Waziristan, one of the seven tribal agencies or districts in north-west Pakistan close to the well-known Durand Line that separates that country from Afghanistan. He already had a Kalashnikov assault rifle slung over over his shoulder though admitted he did not know how to use it.

Michel planned to spend a year in the Afghan maquis and then return to Paris where he owned a small Islamic bookshop; he had sold a part of his business in order to fund his trip. He had left behind in the French capital his wife, of Tunisian nationality, and their young daughter.

The French volunteer fighter said his personal journey began back in the late 1960s when he left home “without a penny to my name” to travel. He had intended to go to Kathmandu but got lost and ended up, in a parlous state, in Karachi in Pakistan where he decided to enrol in a madrassa or religious school. Here he found faith and stayed six years, picking up a solid grounding in religion, as well as a perfect knowledge of classical Arabic, including Arabic verse. By the end of his time there he had became an alim or Islamic scholar and returned to Paris.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

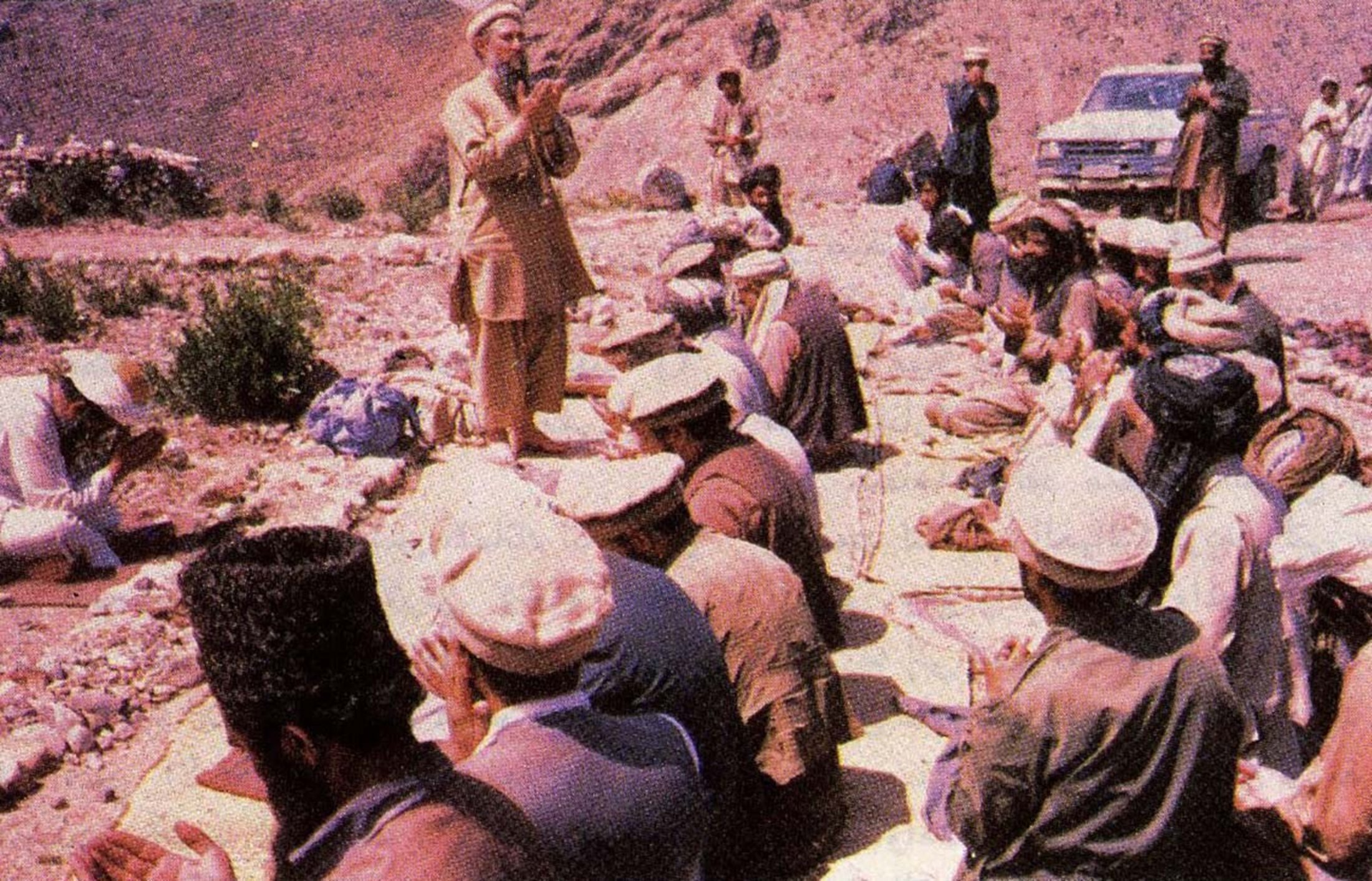

When we encountered Michel in 1985 the war in Afghanistan – which followed the Soviet invasion of December 27th 1979 - was still raging. At the time there was no sign that Moscow would leave the country; in the end, the final Russian convoy crossed the Amu Darya river between Afghanistan and the then Soviet republic of Tajikistan on February 15th 1989. The Soviet invasion was the reason why Michel had come to fight. “Jihad is not an obligation, unless it's decreed by the religious authorities of the country attacked, but it is a duty,” he said at the time. “Each Muslim state has a duty to send a group of volunteers where a holy war is taking place. As the mujahideen of these country get killed they must be replaced by fighters from fellow countries.”

At the time there was no global jihad and no one was thinking about it. The Afghan holy war was solely defensive in nature; it was about defeating a Soviet army which had invaded a Muslim land. Later the focus switched to establishing an 'Islamic Republic', which was the aim of most of the seven groups involved in the Afghan resistance, even though they did not all agree on the form it should take.

Michel A.'s own model was the Saudi kingdom. In particular he liked the strict application of hudud, or Islamic punishments there. “In Saudi Arabia one or two hands are cut off a year but it's enough to stop thousands of thefts. In Pakistan the hudud are really necessary because there's far too much robbery,” he said. He was also in favour of stoning female adulterers.

At the time, 1985, Michel was one of just a small number of volunteers who had come to fight, even though the war had begun five years earlier. There were only around a hundred such foreign combatants at the time, mostly from the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, Jordan, Syria or Algeria. They had come in an individual capacity as the Brotherhood was against its members taking part in fighting and preferred to give the Afghan mujahideen financial and logistic support instead. Three black American Muslims were also part of this small contingent.

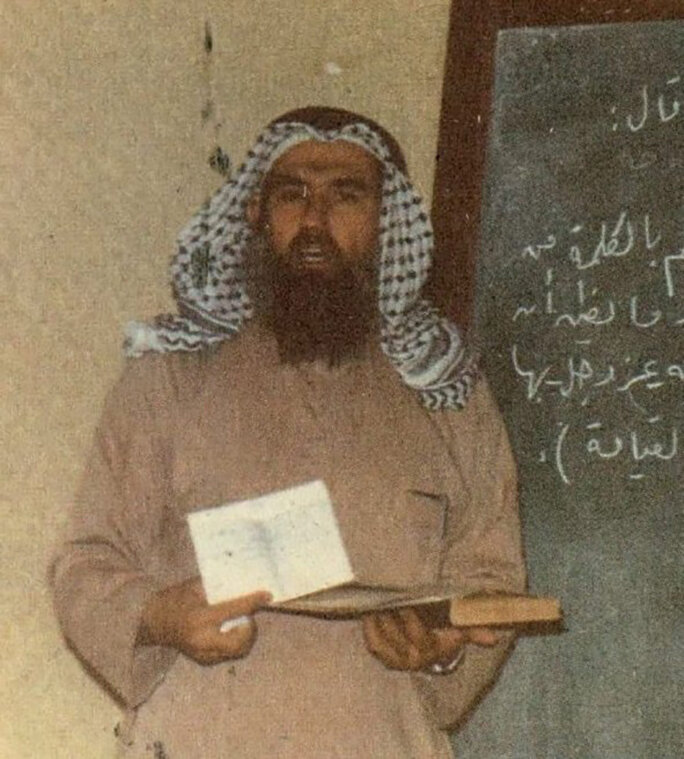

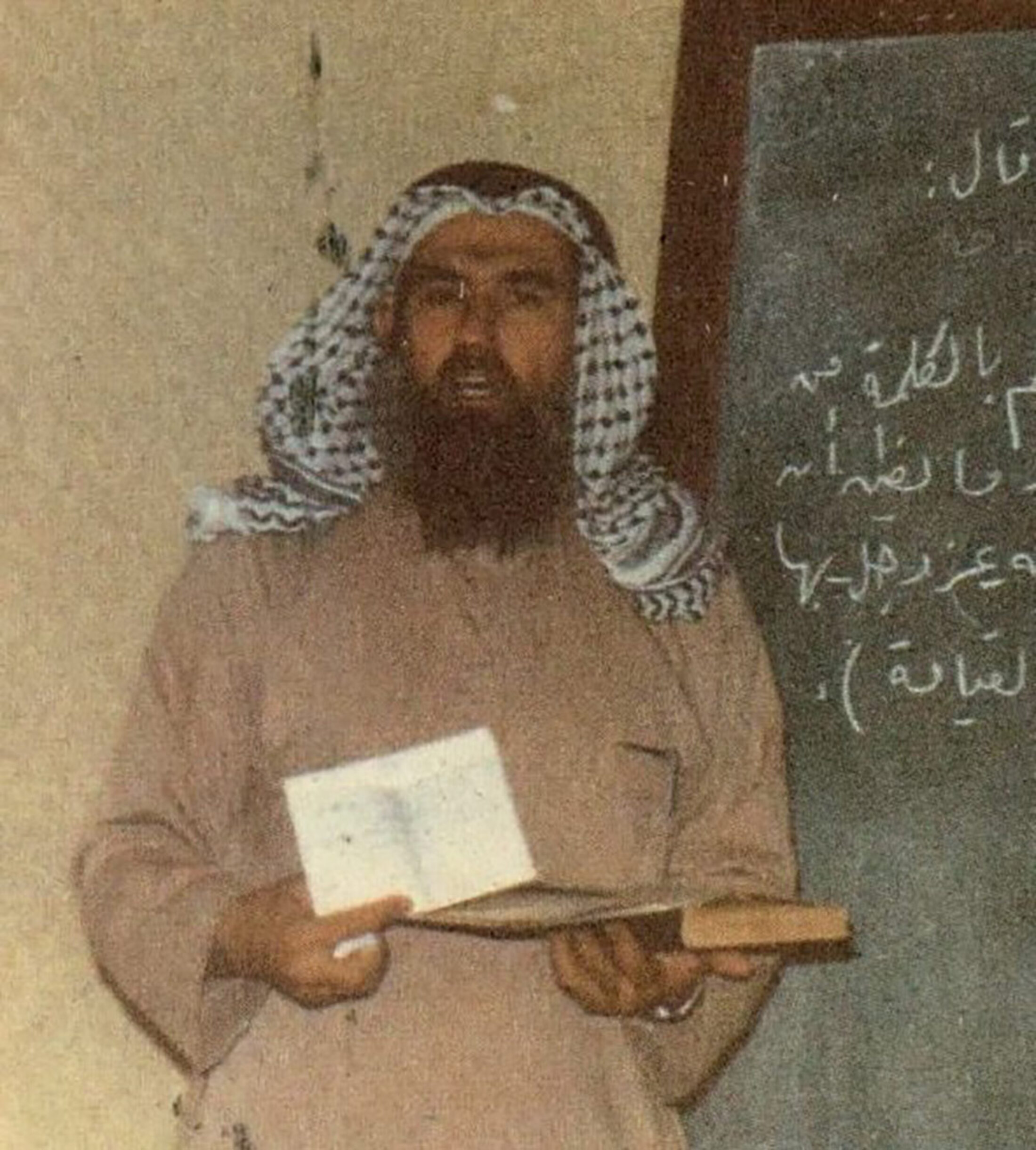

Many of those who came had been mesmerised by a charismatic preacher, a Palestinian intellectual who had become completely committed to the Afghan jihad – Sheikh Abdallah Azzam. Born on November 14th 1941 into a very pious family in a small village near Jenin on the West Bank, in 1985 he published a book which even today remains a major point of reference in the Islamic movement: 'Defence of the Muslim Lands: The First Obligation after Faith'.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

In his work the author developed the idea that Muslims should come and fight in Afghanistan even if their family or governments were opposed to it, that it was a personal obligation for all members of the Ummah or Islamic community. “....If a hand span of Muslim land [is attacked], jihad becomes an obligation for its people and for those near by. If they fail to repel … due to lack of resources or due to indolence, then the obligation of jihad spreads to those beyond and carries on spreading in this process, until the jihad is an obligation upon the whole earth,” he wrote. These words echo the comments of Michel A., the French jihadist.

Another of Azzam's books, 'The Signs of The Merciful in the Jihad of the Afghan', also inspired volunteers. It was an analysis of all the “miracles” that had helped Afghan fighters during their battles.

As a theoretician of jihad, Azzam was head and shoulders above others who started to emerge at this period. First of all the Palestinian had studied a great deal, from the university of Islamic law in Damascus in 1966, where he obtained a degree in sharia or Islamic law, to the Al-Azhar university in Cairo where he received a doctorate in religious studies. His thesis there showed virulent anti-Semitism. This was not just because Israel had invaded the land of his birth but also because he held the Jews responsible for the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, to which he remained attached, and for the creation of communism.

I thought: “Where is the jihad?” I found a parcel of land called Afghanistan, and I tried getting there. God showed me the way there.

In Cairo he became friends with the family of Sayyid Qutb, the radical Islamic scholar, ideologue and promoter of jihad against the “corrupt” regimes of the Arab world; and who was hanged under the regime of President Gamal Abdel Nasser in Egypt in 1966. Azzam then took part in the Palestinian struggles between 1967 and 1970. But he had doubts about the ability of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and was wary of its left-wing ideas and believed that only an Islamic resistance movement could enable the Palestinian cause to triumph.

From 1973 Azzam gained a reputation as a teacher of sharia law at university in Amman in Jordan. His charisma soon earned him the nickname of the 'Jordanian Sayyid Qutb'. He also became one of the leaders of the Muslim Brotherhood in Jordan. He was eventually expelled from that country and in 1980 began teaching at the King Abdulaziz university at Jeddah in Saudi Arabia, a position he obtained thanks to his many contacts within the Muslim Brotherhood.

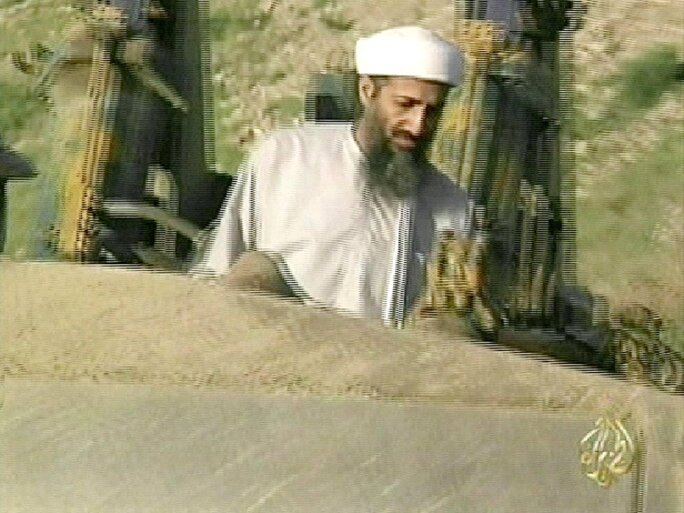

It was at this university that Azzam became first the teacher and then mentor of Osama Bin Laden. The Palestinian later went to Pakistan, initially working as a professor at the University of Islamabad before moving on to Peshawar in the north-west of the country to help those involved in jihad in neighbouring Afghanistan. “I thought: 'Where is the jihad?' I found a parcel of land called Afghanistan, and I tried getting there. God showed me the way there,” he explained in 1989.

In Peshawar the leaders of the Afghan rebellion were seduced by Azzam's huge religious credentials, his great piety and his talents as a speaker. He travelled in Afghanistan with the guerilla movement but did not take part in the fighting. Describing himself as a preacher and theoretician, Azzam was easily recognisable from his emaciated outline and, sporting his familiar brown pakol - the mountain hat worn by people from the Nuristan province of eastern Afghanistan, the first area to revolt against the communist regime in Kabul) - he quickly became a prominent figure in Peshawar where the Afghan resistance had set up its headquarters.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

However, in Azzam's view Palestine was always “more important” than anything else. “Every Arab who can go and fight in Palestine should go there. Those who can't should come to Afghanistan,” he said. One of his supporters later wrote: “The sheikh's body was in Afghanistan but his spirit remained suspended between Nablus and Jerusalem.”

Azzam's popularity benefited from the wave of Pan-Islamism that was sweeping the Arab world at the time. But he revolutionised this theory by proposing that solidarity between members of the Islamic community or Ummah should be extended further by taking part in jihad. “Azzam was the first religious scholar to present an elaborate modern Islamic legal argument for foreign fighting as an individual religious duty,” wrote academic Thomas Hegghammer in his 700-page biography of the Palestinian 'The Caravan, Abdallah Azzam and the Rise of Global Jihad' published by Cambridge University Press in 2020.

Historically, just leading religious figures, such as the ulama in Saudi Arabia, had the authority to call for jihad. The revolution that Azzam introduced was to take this prerogative away from them and transfer it to ordinary believers who from now on could decide for themselves the land to which jihad applied, whether it had been invaded by a foreign power or was under the control of an “impious” Muslim ruler. This is what the political scientist and Islamic expert Bernard Rougier has called “the democratisation of jihad”. In this way jihad became an everyday thing. And not fighting when you have a duty to is a “major sin” in the eyes of god.

In October 1984 Azzam created the Maktab al-Khidamat (MAK), otherwise known as the Afghan Services Bureau, whose task was to collect funds from religious circles and to get Arab fighters to come. It leant heavily on the wide Muslim Brotherhood network and a network of Islamic NGOs. Osama Bin Laden, who had come to Peshawar to join his mentor, was part of the new group's leadership though with no particular responsibility. He held forth all day drinking mint tea or rode beautiful horses – his main passion. Like Azzam, Bin Laden's chief mission was to get volunteers to come. One had the spoken word, the other money. Bin Laden's budget seemed limitless: each Arab volunteer was paid 300 dollars a month.

Nevertheless, it took time before the first recruits started to arrive. They established themselves in a camp on the Pakistan border, in what was dubbed the 'Parrot's Beak', a harsh and mountainous stretch of land that juts in the shape of a comma or a parrot's beak into Afghan territory.

'Get rid of borders'

The anthropologist Georges Lefeuvre, who at the time was director of the French cultural body the Alliance Française in Peshawar, had the privilege of meeting Azzam in October 1989 through a mutual friend, a young Algerian. He described the jihad theoretician as someone quite ordinary looking and pleasant. When they met the Palestinian set out his theories to the French academic.

As far as Azzam was concerned, nation states were a Western invention that the Muslim world does not have to accept. All that should matter is the Ummah or Islamic community, so states need to be broken. This led to a phrase that particularly struck the anthropologist: “We're going to get rid of borders.” But though one would have expected the preacher to have praised the courage of the Afghan mujahideen – who, after all, were taking on the largest conventional army in the world at the time - Azzam did not paint a flattering portrait of them.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

“He saw them as sinners,” said Lefeuvre. “Because they practised the cult of saints and loved Sufis. And he saw their exile [editor's note, at the time five million Afghans were refugees in Pakistan and Iran] as a punishment they deserved. For him, this exile needed to be sacred, he was there to purify them, to sanctify them, and afterwards they had to go back to their own country to purify it in its turn. Afghanistan had to become a land of purity again, from which Palestine, India and even Andalusia could be reconquered.”

According to Azzam, if the Muslim world was weak this was the fault in particular of the “Shiites and Sufis”. The solution was a “return to following the Koran to the letter”. He based some of his predictions on a hadith – words attributed to the Prophet Muhammed – which stated that the Apocalypse will occur once India is 'liberated'; in other words, Islamicised. And that this liberation would emerge from Khorasan, the name given by Arab geographers in the eleventh century to a land which covered modern Afghanistan and parts of Iran and Pakistan. Several other hadiths also refer to it. “When the black flags come from Khorasan go to them, even if you have to crawl on snow ...” says one.

When not based in Peshawar the Palestinian preacher travelled the world to give lectures and raise funds. In the United States, a country he hated because it was in his view the great corrupter of the world, he was a big hit among Muslim communities. In the Al-Farooq mosque in Brooklyn in New York he soon opened a jihad recruitment office.

While in 1985 barely a hundred volunteers had “joined the caravan” - in other words, jihad – four years later the numbers had swollen to around 4,000 Arabs in Afghanistan, most of them in bases in the so-called 'Parrot's Beak' region. Because of a particular status that stretches back to the times of British colonialism, this frontier region – the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) - was strictly forbidden to outsiders. Even the Pakistani army could only go there using the main routes. For the jihadist Arabs it was the perfect place. Moreover, they had the support of the Pakistani secret services the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), who played one of the most crucial roles in the war in Afghanistan.

The jihadists travelled either at their own cost or with money from Islamic charities based in the Gulf states. It was only at the end of the 1980s, when the Afghan cause became a very popular one among young Saudis, that their plane tickets were paid for by the Saudi kingdom's authorities.

These foreign fighters were not always liked by the Afghans themselves, who had never asked them to come and who willingly disparaged them. They nicknamed these outsiders the “asses who bring us money”. Yes, the Afghans were fascinated because these Arabs spoke the language of the Koran, but they criticised them for their sectarianism and their hostility to the Islam of saints and mystics that was common in large parts of Afghanistan.

The local Afghans also criticised the Arabs for trying to convert them to Wahhabism rather than fight. There is some truth in this criticism. In his biography of Osama Bin Laden the New York Times journalist Jonathan Randall established that just 44 Arab fighters – out of a total of 7,000 who took up jihad against the Soviets – were killed. Up to 1985 just four had died in combat.

Bin Laden “came to us from Paradise …. like an angel”

One particular incident, however, raised alarm bells with the CIA. In his investigative book 'Ghost Wars' (Penguin, 2005), about the CIA's secret wars in Afghanistan, another New York Times journalist, Steve Coll, describes how two agency operatives returning from a routine mission on the Afghan border suddenly came across a roadblock set up by jihadists who wanted to kill them. Fortunately one of the two CIA agents was an Arab speaker which saved their lives.

Nevertheless, the incident sparked a stream of messages back to Washington, warning the authorities about these Arab fighters who professed a total hatred of the West and whose actions were worrying both foreign NGOs and many Afghan resistance fighters. But for the Americans the priority remained the fall of the Soviet-backed Mohammad Najibullah regime in the country. So the reports from the CIA on the ground had no effect; indeed, the American financing of the guerilla movement even intensified. The foreign jihadists profited indirectly from this.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

At the time the different parties involved in the Afghan resistance fight against the Soviet-backed regime were becoming more and more divided. There were complex and intertwined ethnic, tribal religious and also ideological rivalries between them. The major divide was the rivalry between the Hezb-e-Islami founded by the Pashtun warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and Ahmad Shah Massoud, a Tajik guerilla commander from the Panjshir Valley in northern Afghanistan.

This was despite the fact that both men came from the Muslim Brotherhood and had followed the doctrine of Sayyid Qutb that favoured takfir or “excommunication”, an approach making it legitimate to eliminate “impious” and “corrupt” Muslim leaders. But the Francophile Massoud was far less sectarian than Hekmatyar; the former listened to the BBC, supported education for girls and accepted female French nurses in his valley, whom Hekmatyar referred to as “Massoud's whores”.

Azzam, who had huge prestige in the region, gave himself the mission of reconciling the two enemies and organised a meeting between them. It did not take place. On July 9th 1989, 31 of Massoud's officers, including eight of his best commanders, were killed by a Hezb-e-Islami leader in an ambush in the Farkhar Valley in Afghanistan.

In this fight to the death between the two warring resistance leaders, the great majority of the Arab volunteers were on the side of Hekmatyar. This was also true of Osama Bin Laden who was hostile to Massoud – 12 years later he sent two Tunisians, Dahmane Abd al-Sattar and Rachid Bouraoui el-Ouaer, to kill the resistance fighter.

As for Azzam, he tried to stop this fitna or religious discord. Yet at the same time he almost seemed to worship Massoud, to the point where in one press conference he compared him to Napoleon. According to Azzam's son-in-law, Anas Hussein, a former jihadist from Algeria, who described the ten years he spent in Afghanistan in 'To the Mountains – My Life in Jihad from Algeria to Afghanistan' published by Hurst in 2019, Hekmatyar and Bin Laden were offended by this adoration. The pair thought that Azzam came close to “idolatry”, one of the worst sacrileges in the eyes of Islam.

This was not the only point of disagreement between the master and his former pupil: Azzam was opposed to any extension of the jihad to outside of Afghanistan, at least while the country had still not been freed from the “impious” who ruled it. What good was it, he argued, calling for holy war against President Hosni Mubarak in Egypt or Benazir Bhutto, who was then prime minister of Pakistan, when the communist regime still ruled in Afghanistan? That was not the view of Bin Laden who was already thinking ahead to after Kabul had fallen and dreamed of extending the frontiers of jihad.

Azzam was worried about seeing his former pupil Bin Laden growing distant from him and leaving the Services Bureau or MAK, with a large number of his volunteers. We know from Anas Hussein that relations between Azzam and Bin Laden had started to worsen in 1987. One man in particular contributed a great deal to that rift: the radical Egyptian doctor Ayman al-Zawahiri, who had been jailed in Egypt. Azzam felt that Bin Laden had fallen under al-Zawahiri's influence and that of the most radical Arabs. “I am very angry with Osama. This man came to us from Paradise, like an angel. (But) I'm worried for his future if it remains with these kind of people,” he told his son-in-law.

Indeed, soon afterwards, in August 1988 and amid the utmost secrecy, Bin Laden and al-Zawahiri set up a new organisation which appeared to be a split from the Service Bureau. Its name was rather mysterious too: Al Qaeda or “The Base”.

But Azzam should have been more afraid about his own future. On November 24th 1989, as he went to the Saba-e-Leil mosque in Peshawar to lead Friday prayers, a car bomb killed the Palestinian preacher and two of his sons.

Thirty years on and mystery still surrounds this assassination. There was no lack of suspects. According to Azzam's biographer Thomas Hegghammer there are no fewer than nine theories. Was it Hekmatyar, who never hesitated about killing his opponents? Ayman al-Zawahiri, because of the rivalry between Azzam and the Egyptian jihadists? The Jordanian secret services? The Afghan secret service KHAD, even though they were very weak at this time? Israel, the CIA or the KGB? Or perhaps even Osama Bin Laden, even though this theory lacks credibility? What is certain is that the Pakistani secret services know the truth.

The killing gave Azzam martyr status. And it made him an absolute icon in the Islamist movement; there are now countless mosques, streets, religious centres and websites that bear his name in the Arab world. Some armed groups, such as Ahrar al-Sham, in Syria, claim allegiance to his views. His writings have also influenced generations of both radical and less radical militants. For the jihadist movement his assassination was equivalent to the shooting of JFK for Western countries.

Today, one question haunts scholars: if Azzam, who professed violent anti-Western feelings and who hated America, had not been killed, would he have supported the attacks of September 11th 2001? “There is no doubt that the Azzam of 1989 would not have endorsed the 9/11 attacks, because in his lifetime he never advocated jihad against the West, international terrorist tactics, or even suicide bombings,” writes Thomas Hegghammer. “The real question is whether he could have evolved into a person who would have endorsed such tactics. We must bear in mind that in the late 1980s nobody had proposed global jihad against the West, not even Bin Ladin himself.”

However, Azzam's death was an opportunity for Bin Laden to take his place as the “heart and brains of jihad”, even if he did not have the same religious credentials, and to give it a new direction and to lead in complete freedom – along with Ayman al-Zawahiri – the new and mysterious secret organisation Al Qaeda.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter