Following the first formal complaint for rape filed with French police against the prominent Islamic scholar and preacher Tariq Ramadan last month, several other women have come forward to separately accuse him of rape and sexual assault, and the growing scandal resulted earlier this month in him taking leave of absence from his prestigious post as professor of contemporary Islamic studies at Oxford University.

"An agreed leave of absence implies no presumption or acceptance of guilt and allows Professor Ramadan to address the extremely serious allegations made against him, all of which he categorically denies," said the university in a statement on November 7th.

Yet other women have now spoken out about having had consenting extra-marital affairs with Ramadan, 55, accusations which, while not subject to eventual legal proceedings, are in stark contrast to his high-profile image as a rigorous Islamic intellectual.

Ramadan, a Swiss national and the grandson of Hassan al Banna, a founder of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, has vigorously denied the sexual assault and rape accusations against him and dismissed them as being “a campaign of calumny”.

Ramadan failed to respond to Mediapart’s repeated requests for comment before this article was first published in French. Also contacted by Mediapart, his lawyer Yassine Bouzrou replied: “I do not wish to communicate.”

The controversy now surrounding Ramadan, who holds a number of academic positions in educational institutions around the world, began in the wake of the first accusations of rape and assault against Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein. As the avalanche of claims against Weinstein began appearing in early October, an unprecedented wave of allegations of assault and harassment by various other individuals began flooding social media. The first claim against Ramadan was made on October 20th.

The cases of Weinstein and Ramadan have a common element in as much that they have emerged when both men, widely feted by the media, entered a stage of professional decline and dwindling power.

Ramadan, a tireless conference speaker, a visiting professor at universities in Qatar and Morocco and a research fellow with another in Japan, a polyglot and the author of more than 30 books published in French and 15 in English, has enjoyed a high profile in many media worldwide. His rise to fame and academic recognition during the 1990s was as the figurehead of a new generation of activists and gave him a large audience across the Muslim world, while he also drew fire from critics, notably in the West, who accuse him of holding an ambiguous position with a covert agenda of radical Islam.

But over recent years, Ramadan began losing his perceived role as a structuring leader of Islamic thought. While some withdrew their support of him, he also came up against attempts to bar him from public venues; former conservative French prime minister and mayor of Bordeaux Alain Juppé last year sought to have him banned from attending a conference in the city in south-west France on the basis that he represented a potential risk to public order. “The expressed views of Tariq Ramadan are ambiguous and dangerous,” argued Juppé. After Ramadan announced in early 2016 that he was going to apply for dual French nationality, the then French prime minister Manuel Valls dismissed the idea, saying that the “values” of French society were “contradictory to his [Ramadan’s] message”.

It was within this context of declining sway, and amid the torrent of accounts of alleged sexual crimes addressed via the #Metoo hashtag and its French equivalent #Balancetonporc (denounce your swine), that the first woman came forward with the rape claim against him. Henda Ayari, a former Salafist activist who has since espoused the feminist movement as a non-believer, lodged a formal complaint against Ramadan on October 20th for raping her in a Paris hotel in 2012 when, she said, ‘I thought I was going to die”.

“I am really going to need support my friends,” she wrote on her Facebook page shortly after filing her complaint, “because by denouncing the name of my attacker, who is none other than Tariq Ramadan, I know the risks I am taking.”

One week after Ayari lodged her complaint with police, a second woman, identified only as Christelle, came forward with a similar accusation that she had been raped by Ramadan, this time in his hotel room in the French city of Lyon in 2009. Christelle, a French national who converted to Islam, detailed in her complaint to police that Ramadan had slapped her about the face, on her arms and breasts, and also punched her in the stomach, before forcing her to perform fellatio and sodomising her. She said that after that he again beat her and raped her with an object. In her statement to police, revealed by French dailies Le Monde and Le Parisien, she said: “I didn’t understand anything, I had tears in my eyes […] I cried out in pain, shouting ‘stop!’.”

The accounts of the two women are both detailed and similar. They have subsequently been separately questioned by police in a preliminary investigation opened by the Paris public prosecutor’s office.

Also at the end of October, French daily Le Parisien published an interview with a woman, whose identity it protected under the false name of Yasmina, who claimed she was the target of sexual harassment and threats by Ramadan.

Six days later, in early November, francophone Swiss daily La Tribune de Genève published claims by four former pupils of Ramadan that they were invited by him to have sexual relations during the 1980s and 1990s when they were aged between 15 and 18. One of them described sexual acts that were “consented but very violent”. Another said: “My head was filled with confusion […] He said it was our secret”. Another, who said she was aged 14 at the time, spoke of Ramadan’s anger when she refused his advances, describing a “twisted man, intimidating”, who was “possessive and jealous”, who used “relational and perverse strategies” and who “abused the confidence of his pupils”.

Tariq Ramadan has vigorously denied the accusations, filing four lawsuits in Paris and Geneva; two of these are for “calumnious denunciation”, another for “defamation” and another for “corrupting a witness”. In several statements, he has described the claims against him as “anonymous allegations”, and a “campaign of calumny” launched by his “longstanding enemies”. In a statement dated October 28th, he said: “The law must now speak […] we are ready for a long and bitter combat”.

On November 11th, he published a message in English, French and Arabic on his Facebook page saying his lawyers had requested he stay silent “far from media deadlines and excesses”, while he deplored a “deleterious climate”.

“From all sides, whether anonymous or not” he continued, “we read comments that are excessive, racist, anti-Semitic, Islamophobic, dismissive of women, and worse. For more than thirty years I have called for balance, for careful listening, for respectful dialogue and for open and critical intelligence.”

On November 15th, Ramadan’s lawyers sent the Paris public prosecutor’s office the contents of a private conversation between him and Henda Ayari, which was held 15 months after the date of her alleged rape and assault by him. Ayari has said that she had continued to correspond with Ramadan in writing, but that the exchanges ended in insults after she refused to send him a photo of her naked.

Meanwhile, over the past year, a team of lawyers have benevolently acted as legal counsels to several women who have denounced the behaviour of the Swiss scholar. “They are Muslim women, in social and spiritual disarray, who he hooked on Facebook,” said Calvin Job, one of the lawyers. “They were under influence and believe they were victims of sexual predation. He proposed marriage to some, while lying about his real matrimonial situation, while to others he spoke about sexuality and covered the stages more or less quickly. A priori there is not a case of criminal offence, but there could have been a dimension of taking advantage of vulnerability.”

Job said he and his colleagues were certain that “the Ramadan affair is a ‘chest-of-drawers’ case” and that to “encourage and accompany the liberation of speech, to be listening” is required. “There is serious caution on their part, because they dread the potential of trouble-making by Tariq Ramadan and those close to him, but also because it is very complicated to prove harassment.” Over the past year, the lawyers have recorded the statements of the women and elements that support their case, Job said, “if ever they move beyond the point of fear and decide to talk openly”.

“The justice system is a world of the rich, of Whites, which they don’t know about,” added Job. “Our message was to tell them that we were accessible, that we weren’t the lawyers of the powerful, but those of the just.”

The pool of lawyers are backed up by Thomas de Gueltzl, a French lawyer specialized in cases of online harassment. “If these women decide to speak out in public, a wave of hate could be released, with harassment, comments, threats, and which would not be necessarily directly linked to Tariq Ramadan’s team,” he said. “Our role is to protect them.” Henda Ayari, the first woman to come forward with a complaint for rape against Ramadan, spoke earlier this month of how she has since been subjected to “hundreds” of threatening messages via the internet, including death threats, “anonymous phone calls” and buzzing on her apartment bell, about which she has also filed a complaint.

Legal threats from a mysterious 'lawyer'

A major question now is why the numerous and detailed accusations against Ramadan never publicly surfaced before last month. Several people questioned during this investigation said they were aware of his “reputation” as a seducer, some even describing a man “obsessed” by sexual prowess, but none spoke of having knowledge of allegations of rape.

However, some women apparently did take steps to sound an alarm with reports of his improper behaviour, with tidbits of the claims posted on social media discussion forums; videos and sound recordings alleged to have been made by the Islamic scholar were published online via YouTube and Facebook before being swiftly flagged up and deleted.

Majda Bernoussi is one woman who claims she tried, in vain, to alert attention to Ramadan’s behaviour. A Belgian national of Moroccan origin, she said that in 2014 she became ill after a “chaotic, destructive” relationship with Ramadan that had lasted four years. According to her, she posted several video accounts of her claimed liaison with Ramadan, which have since been removed, and wrote an 81-page account of their relationship, Un voyage en eaux troubles avec Tariq Ramadan (‘A journey in troubled waters with Tariq Ramadan’) which was never finally published.

A number of journalists were contacted by those claiming to have been victims of Ramadan’s behaviour, including Ian Hamel and Caroline Fourest, both of whom have written biographies of Ramadan, and also journalists from French dailies Le Parisien and Le Monde. But because no formal complaints had been filed, and because the allegations were made anonymously, they decided that the evidence to support the allegations against Ramadan was too weak to be published in face of the risk of legal action that might be taken against them. “I knew since 2009,” wrote Fourest on her blog in a post on October 28th. “Just before my scheduled duel with him on [French TV channel] France 3, victims began contacting me. I met them. They showed me explicit photos and gave horrific accounts, but the assaults suffered remained impossible to reveal without [resulting in] lawsuits.”

Bernard Godard was an advisor on issues concerning the Muslim faith to the French interior ministry between 1997 and 2014. In an interview with French weekly newsmagazine L’Obs he said that he was made aware that Tariq Ramadan “had lots of mistresses”, that he “consulted websites” and that “girls were brought to the hotel at the end of his conferences”, that Ramadan “invited some to undress” and that when some refused such overtures “he could become violent and aggressive”. Questioned by Mediapart, Godard said that in the period “2009-2010” he received “two indirect accounts” from people who knew Ramadan: “They told me, ‘recently we have rumours saying that he has become a bit more violent’. It happened that he asked girls to go to his room and he could be insistent, pressing, even violent if the girl resisted – verbal violence, he insulted them. But I never heard about rapes.”

Godard added: “It was like, ‘I have heard said that…’, and in the context of six or seven years ago, when harassment was wrongly perhaps not taken into consideration, one said, sadly, that ‘that’s not normal’, full stop.”

Some of Ramadan’s alleged victims have suggested that the absence of any alarm over his alleged conduct was because of threats and intimidation directed towards them, as well as the threat of revelations of compromising videos. That is the claim of Sara (whose real name is withheld), a 36-year-old from the Hérault département (county) in the Languedoc region of southern France. She said she had never met Ramadan physically, but engaged in correspondence with him in 2013 that became sexually explicit. She recounts that she questioned him over his intentions, and his contradictions with what he proclaimed to be his “religious values”, before deciding to disclose on social media her own experiences and those of other women with whom she was in contact. “I understood that he used his image to attract girls,” she told Mediapart. “He blocked me out of all apps and networks. I created a false Facebook account and I left a comment under a publication where he spoke of respect, while questioning about his respect for women. The message was effaced.” She said that shortly afterwards, another woman contacted her via a private message. “She tried to squeeze out information from me. The next day, Tariq Ramadan sent me screenshots of the conversation I’d had with this lady, telling me to be careful with who I spoke to.”

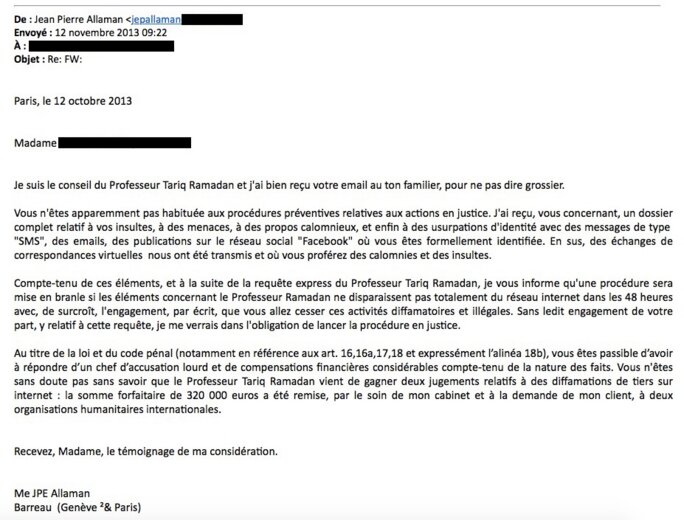

Sara said that Ramadan subsequently claimed he did not know her, and warned her that he might denounce her for “harassment”. In November 2013, she received two emails from a person presenting himself as a lawyer registered with the bar of Geneva and Paris named Jean-Pierre Allaman, and who represented Ramadan (see below).

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The email messages signed by Allaman that Sara has presented to Mediapart do not contain the usual legal presentation expected of a lawyer, and offer no address or phone contact numbers. Mediapart could find no trace of him in the records of the Paris or Geneva bars, and a search on the internet produced no mention of him as a lawyer. If Tariq Ramadan himself was the author of the email message, that would constitute a criminal offence. Contacted by Mediapart, Tariq Ramadan failed to respond to our questions on the subject.

Sara subsequently received other email correspondence, this time from existing lawyers’ practices in Geneva and Brussels. They accused her of “harassment” and “violation of personal privacy”. In one such correspondence, a woman lawyer in the Geneva law firm explained she was following up on the action undertaken by her “colleague” Jean-Pierre Allaman. Contaced by Swiss daily 24 heures, the lawyer said she had no knowledge of Allaman. Questioned by Mediapart, neither practice offered any comment on the correspondence, invoking “professional secrecy”.

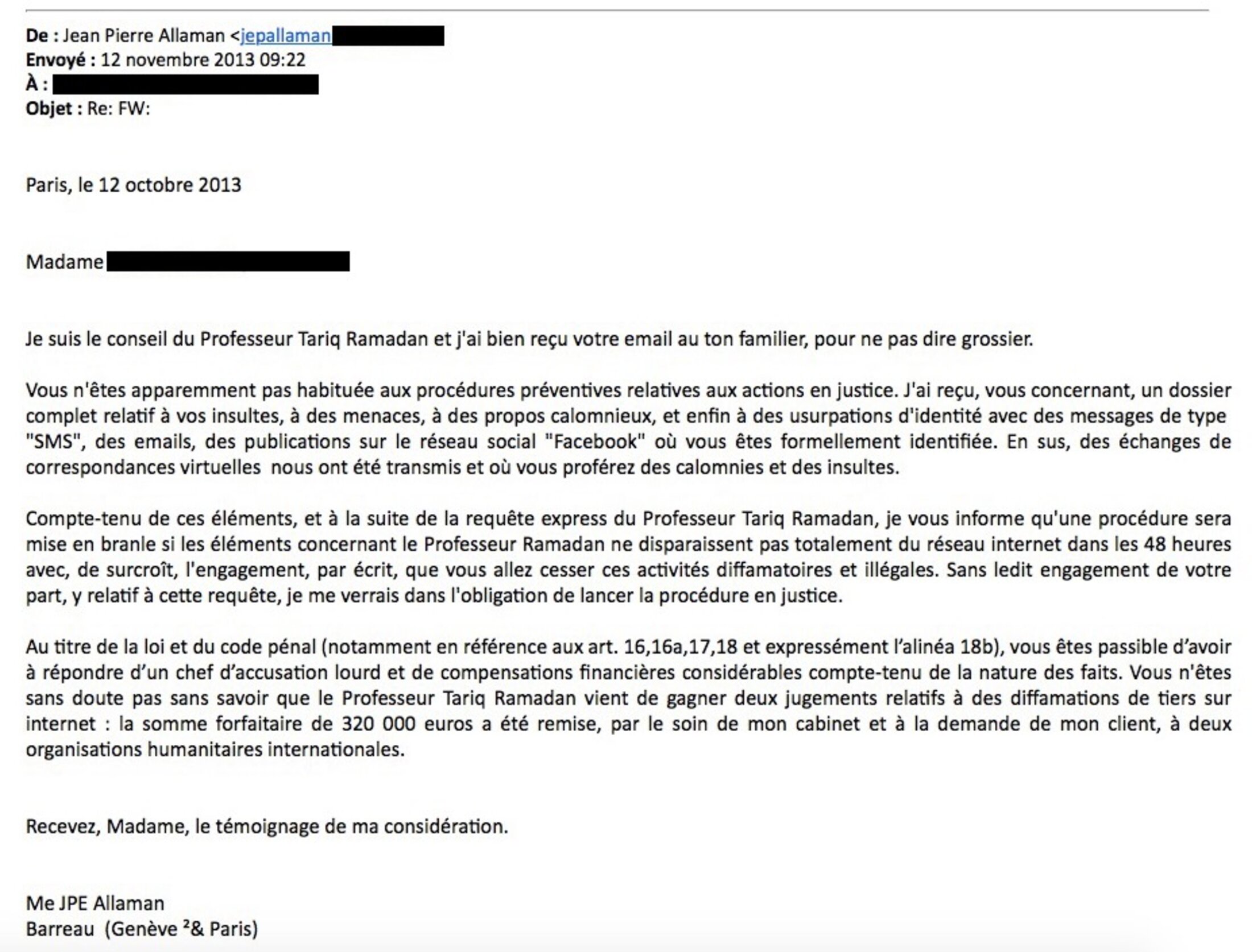

But the matter did not stop there. Sara said she later received an intimidating email (see below) from an individual who presented himself as Ahmed Mawlawi, who said he was formerly “close to Tariq for a long while”. In the message she passed to Mediapart, he warned her that if she continued to publish comments about Ramadan on social media, he – Mawlawi – would divulge personal details about her.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Mediapart’s attempts to contact Mawlawi via his Gmail address which figured on the copy of the email prompted no response, and Tariq Ramadan has declined to comment on whether he was in fact the author of the message. Meanwhile, Sara says that she has seen several Facebook accounts with her name emerge, which she says she suspects were instigated by Ramadan, while another woman who has alleged improper behaviour by Ramadan, Lucia Canovi, claims to have subsequently received emails from a Gmail account in the name of Sara.

Lucia Canovi is a French national who converted to Islam and who lives in Algeria, the author of a book published on October 12th entitled Le Double Discours. Tariq Ramadan le jour, Tariq Ramadan la nuit (‘Double speech: Tariq Ramadan by day, Tariq Ramadan by night’). Canovi is herself a controversial figure, who has posted videos online such as one (see here) explaining that the Earth is flat, or another alleging that Tariq Ramadan is a Satanist. In her book about Ramadan she accuses him of engaging in what she has called “sordid adventures”, and that and other accusations posted on the internet have prompted legal warnings from Ramadan and his lawyer. But she has also received threatening emails. One warned her: “Continue with your work which consists of criticizing, dirtying and stirring up mud and you will suffer the consequences with your family and your children” (see below; this report continues page 3).

'His fans rush to his conferences. He’s a bit like god.'

“At the beginning, he asks you lots of questions about the family, travels and so on,” said Sara. “He tries to figure out the person, their weaknesses. He also asks women for photos, videos, of a bit sexual in nature, and he tries to intimidate you.” She gave the example of a married mother who she said had a relationship with Ramadan. “He had a video of her performing fellatio on him, so he blackmailed her with that,” claimed Sara.

The woman interviewed by French daily Le Parisien, and whose identity was protected under the false name of Yasmina, echoed Sara’s account: “He would say that he had compromising things on me,” she told the paper. “He used his aura in the community and took advantage of my weaknesses.”

Henda Ayari, the first woman to come forward last month with her complaint against Ramadan for rape, said that when she first informed him of her intention of lodging a complaint he threatened “retaliation” against her and her children and also that he would release “compromising photos” of her.

“There were threats each time these women wanted to speak out,” said Ian Hamel, a journalist with French weekly magazine Le Point and the author of a biography of Ramadan in 2007, and who has met several women claiming to have been victims of Ramadan. “They assured me that he intervened himself on social media, using various pseudonyms, to insult his detractors. He was also capable of calling their older brother or father.”

Hamel said that Majda Bernoussi was threatened in “vocal messages” and in “correspondence from lawyers of whom no trace is found in professional directories”. He himself had received “insults” and “threats” from Ramadan during the preparation of his biography. “During an interview he could change his attitude within two seconds if you say something that displeases him,” he said.

Over time, some of Ramadan’s accusers came into contact with each other, and according to Sara he tried to turn them against each other. She cited the example of an email dated November 27th 2013 in which Ramadan told Sara that Majda Bernoussi had “a real psychological problem” and regularly suffered from “crises” and “jealous frenzies”.

“To Majda, he said that I was frustrated because he had rejected me,” said Sara. “To me, he said that she was mad.”

Hamel met Bernoussi in 2014, when she explained how she had first contacted Ramadan after returning from a trip to Mecca, when she sent him notes about her life which had been marked by violence. “Have confidence, I will guide you towards the light,” Ramadan allegedly told her. “He’s a guru,” said Hamel. “His fans, notably young women, rush to his conferences. He’s a bit like god.”

Enlargement : Illustration 6

Earlier this month, French weekly magazine L’Obs published an interview with a woman identified as Naïma, who said she had an “extremely toxic” but consenting relationship with Ramadan. “After passing through Tariq’s hands, you are not the same person,” she recounted. “He takes possession of the mind of the other.” Naïma described Ramadan as a “predator”. Another woman interviewed by the magazine, Amélie, said he, “sometimes went over the top in his control of me”. She cited mobile phone text messages she said she received from him: “You were supposed to be submissive and obedient”, “You must answer me quicker and you must obey me”, and “Are you really happy that we know each other? With intelligence, the body and the mind? You feel that a bit?”

“One time he said he was my sultan,” she added. “As soon as there was the slightest disagreement, or if I didn’t answer his text messages within ten minutes, he went into angry outbursts, then in the middle of the night he would send me a message ‘I’m thinking of you’. I had the impression of having the clashes couples have with someone who I had met twice, and who was in no way my partner. He made passionate, lyrical declarations to me. I didn’t know if it was manipulating or sincere.”

Questioned also by Mediapart, Amélie (whose real name is withheld) said her relationship with Ramadan began with a message she received from him on Facebook in August 2011, when she was 22-years-old. She said she had never met him before, having seen him only on TV. “He was somebody I admired a lot, even if I wasn’t a Muslim at the time,” added Amélie, who later converted to the faith. When she received his message she said she thought it was a hoax. “It seemed impossible to me that it was him,” she recounted. “There was no reason he would send me a message, I’m nobody.”

She said she ignored the contact and that several days later a second message arrived from him, expressing his surprise that she had not answered the first. He explained that he had read an interview with her about the Palestinian cause and had “a project” to propose her. “I’m not a very dedicated militant so I was sceptical,” she said. “I told him to call me if it really was him.” According to her account, he called her three weeks later and suggested that they meet “in a discreet place” which was a restaurant close to the Gare de l’Est railway station in Paris. She said she accepted in order “to find out what was behind all that”.

She claimed that Ramadan very soon addressed her in a familiar manner. “On the way there, I sent him a text message to tell him that I would be a bit late,” she said. “He replied ‘Oh, don’t start that’, ‘Hey there the young thing who’s late, authoritarian, who doesn’t answer. Ther’s some punishment missing there.’ I found that bizarre.”

Amélie said that after she arrived at the restaurant she asked him what it was he wanted: “He replied that he was there for what might interest me, discussions, projects, relations. He said my personality had touched him in the interview, and that I pleased him.” She claimed that very soon after their meeting she received from him mobile text messages that were “very sexually explicit, in which he talked a lot about relationships of sexual domination”.

“He said he wanted that I give myself to him entirely, body and soul, he spoke to me of fellatio, then sodomy,” she continued. “I was very shocked, we hadn’t yet ever touched each other, I had seen him just once. I told him that I wanted to go more slowly. He criticized me for not giving enough, for being too cold, too distant.” She said they agreed on a second meeting, this time in a café. “Firstly he played footsie. After that he asked me to go to the toilets and to wait for him there. I said no, it was out of the question.”

Sara recounted that she was contacted by Ramadan in May 2013 after she left a message on his official Facebook page which read “Good-looker Tarik [sic], haven’t you a son or a cousin you can present?” and which she said was deliberately “to mock” the messages from his fans. She claimed that she was subsequently contacted by an account in Ramadan’s name in which he invited her to connect on Skype. She said that believing at first that the message was not from Ramadan but a hoax, she refused and alerted his official Facebook page to the incident.

Mediapart has listened to a sound recording of a message she said she subsequently received from Ramadan. “There you are, this way you hear my voice, then for you to know. It is truly me, so I’m not going to start insisting for 30 years,” the voice stated. Sara said she turned down a proposition to meet at a Paris café. In their exchanges on the Viber app, which Mediapart has seen, Ramadan alternated sexual allusions with other comments in which he reproached her for having a “cold attitude”, asked her to “give more” and to be “more free without any fussing”, to “Be present”, to “Let yourself go and be in confidence”, and declaring “I need more”.

Threats of a 'terrible punishment' for accusers

Amélie spoke of how she was invited on two occasions by Ramadan to join him, late at night, in his hotel room. She refused the first time but accepted the second invitation. “I was in a very depressive phase,” she said. “I wasn’t sleeping, I wasn’t feeding myself, I felt very alone, and on my birthday he was the first to send me a message. I was touched, and it’s the only time I dropped my guard. I said to myself, ‘After all, he takes an interest in me, he’s kind’.”

Amélie claimed that at the hotel Ramadan began their encounter calmly: “He didn’t jump on me, he offered me a present, and we talked.” But as they undressed, according to her account, he bit her breasts so fiercely that she had “scabs of blood several days later”.

“It’s a practice that I found violent and that I hadn’t wanted,” said Amélie. “I told him ‘I don’t like that’. He said to me, ‘I know, that’s why I did it’. I found that very, very shocking. I broke down in tears.” She said that when he went to the toilet she took the opportunity of pretending she was asleep and stayed so for four hours:“I was terrified. I kept my legs crossed, tight. He didn’t touch me. He stayed awake all night, sitting, with the light on. He wasn’t doing anything. He didn’t go about his morning prayers. Every 30 minutes he called to me ‘Are you OK, are you sleeping?’.”

Amélie said she has no intention of filing a complaint against Ramadan because their relationship was consensual. But she has now contacted a lawyer, believing that her account of her relations with Ramadan could serve to help the police investigations underway into the other cases.

According to several women, during conversations the preacher is quite swift to move on to other subjects than religion or spirituality. According to Majda Bernoussi, “very quickly” the subject “didn’t interest him any further”, she said in an interview with journalist Ian Hamel. “He told me he had fallen in love with the girl from the manuscript,” she said, in a reference to the texts she had written about her life and which she submitted to Ramadan. “He demanded my total confidence in him. He said he was divorced before god and men. I believed him.”

The woman interviewed by French daily Le Parisien and whose identity it protected behind the false name of Yasmina said that at first she received religious “guidance” from Ramadan, as she had requested, and then “one day” he asked for her photo.“He wanted to know what the person with whom he was corresponding looked like,” she said. “He found me pretty. From then on everything between us went off the rails, it became pornographic.”

Amélie, meanwhile, said she “very quickly understood” what Ramadan was interested in, and that it was not “the project” about the Palestinians. “He hardly spoke of it, and then in a very vague manner,” she said, adding that the fact that he was a “public personality” and a “moral guide” intimidated her. “I would say to myself ‘I’m talking to Tariq Ramadan, it’s crazy!’. I would blush. He told me, ‘You please me’. I asked him if he was married and how that appeared to him compatible with the Muslim religion. He didn’t really manage to answer me.”

Most of the women who have come forward to level accusations against Ramadan explain that they were going through a very difficult personal period when they were in contact with him. Majda Bernoussi had detailed to him her painful experiences, while Amélie was coming out of a relationship with a boyfriend who harassed her, and was suffering from serious depression. Naïma said she was at the time “swallowed up with problems” and that she told herself that, “He’s not just anyone, he should be given confidence”.

Henda Ayari, the first to file a complaint for rape last month, was in the process of a difficult separation from her Salafist husband. “I had lost the custody of my three children,” she said in an interview with Le Parisien. “I was alone, without money, without a place to live, without work. A social services worker advised me to take off my veil to find a job. I followed her advice, but I felt guilty [...] Tariq Ramadan brought me the answers that I was looking for.”

Some of the women claim that Ramadan asked them to keep their relationship with him secret. Amélie said he cut off all contact with her in October 2012 after learning that she had told the head of a Muslim association that she had met him “a few times”, and she says she received a message from Ramadan accusing her of betrayal.

“For a long time, Tariq Ramadan appeared to be untouchable,” commented Saïd Branine, the director of a French-language Muslim news website called Oumma. “He’s someone who doesn’t accept criticism at all and can show himself to be very threatening towards those who contest him. Some women could have been afraid to talk, they most certainly fear threats from him or those close to him.” Branine added that Ramadan had accomplished “a master stroke” by “identifying himself as a defender of Islam and to let it appear that when he was being attacked it was systematically an attack upon Islam”.

Over recent years, some former allies of Ramadan who subsequently fell out with him have been reticent in openly criticising him, apparently for fear of contributing to a stigmatisation of him, and also that it would produce a backlash against Muslims in general.

Sociologist Omero Marongiu-Perria, a former member of the Union of Islamic Organisations of France, the UOIF, said he believes this silence is also due to Ramadan’s celebrity and the important networks surrounding him. “He has achieved a significant celebrity, thanks to his charisma – he presented himself as a charming man, perfectly mastering the French language – to his filiation – he is the grandson of the founder of the Egyptian Muslim Brotehrhood – but also thanks to an infrastructure he constructed.” Marongiu-Perria underlined that Ramadan “has never been the son of immigrants from the [poor] neighbourhoods, a self-made man nor an isolated man”, but that instead he was born into “a bourgeois family and subsequently built himself up a network of militants and elites”.

Marongiu-Perria, who has written a widely commented article about the Ramadan scandal on Oumma, said that during Ramadan’s ascension in the 1990s, he “removed one by one” those who were critical of him. “When militants criticized his strategy or views, he would retort, ‘These are people who want to take my place’ or that ‘they are subservient to the system’,” he said. “It is this same strategy of defence that is used today in the cases of sexual violence.”

The silence may also reflect the fear women have of the reactions of those close to them within the Muslim community, where “the taboo surrounding sexuality is important”, according to Oumma director Saïd Branine. “Some women dread the shame before their husbands, father or brother,” he said, “comments like ‘why did you find yourself in a hotel room with someone you don’t know?’.”

Lawyer Éric Morain, who represents several women who have denounced Ramadan, including Christelle, the second alleged victim of rape by Ramadan to come forward last month, underlined the difficulty for his clients to testify. “These women had placed a ‘lid’ on what happened, and are today logically in a process of gestation, but which has a boomerang effect,” he said. “With all of that having become public and high profile in the media, they feel exposed. Indeed, they receive a whole lot of diverse threats and pressure. They have a social, cultural and religious life, so some people, including within their families in fact, are able to tell them that it would be best not to talk. And despite that, some of them do.”

During this Mediapart investigation, several people we spoke to said that Tariq Ramadan’s brother, Hani Ramadan, the director of the Islamic Center of Geneva, was alerted both in writing and orally to the accusations levelled against him. Mediapart was told that he regarded the allegations as being a question of his brother’s private life, while suggesting the women who denounced Ramadan were at fault in the matter. Hani Ramadan did not reply to Mediapart’s attempts to contact him.

Since the beginning of the scandal last month, Hani Ramadan has dismissed the accusations against his brother Tariq as being “calumnies”. In a message in a video placed online after Henda Ayari announced she had filed her complaint against Tariq, Hani Ramadan denounced “malicious gossip” and “rumours” while predicting a “terrible punishment” for those who accuse “an innocent individual of having fornicated or raped” by giving an account that is “the fruit” of their “malicious imagination”.

CALOMNIES ET BOURDE D'EURO-ISRAEL - A DIFFUSER LARGEMENT S'IL VOUS PLAÎT https://t.co/T89sbDeHlf

— Hani Ramadan (@_HaniRamadan) 29 octobre 2017

On October 29th, on his blog on the website of Swiss newspaper La Tribune de Genève, and on social media (see above), Hani Ramadan called for his readers to relay a document which blamed the scandal surrounding his brother Tariq on a Zionist plot. The blogpost was subsequently removed.

On November 11th, Tariq Ramadan wrote on Twitter that he remained “serene”, “patient” and “determined” and that, “I have confidence in the justice system”.

Meanwhile, Christelle’s lawyer Éric Morain said he expected a lengthy period of investigation. He added that he is considering the possibility that other women might testify in anonymity, “within the framework allowed” by French criminal law.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse