To this day no one knows for sure how many died. On December 1st, 1944 dozens, perhaps scores, of African troops who had just returned from Europe where they had been held as prisoners of war by the Germans were gunned down by French soldiers at Thiaroye military camp near Dakar in Senegal.

The official verdict is that troops from the so-called Senegalese Tirailleurs or colonial infantry had staged an armed revolt in protest over not being paid the money they were owed by the French authorities for their war-time service. Relatives of the African troops killed that day or later jailed for rebellion, insist, however, that the French army who had been guarding the African troops in a holding camp awaiting discharge took part in what amounted to a massacre.

One of the African troops prosecuted after the killings was Senegalese soldier Antoine Abibou, who on March 5th, 1945, was handed a ten-year-sentence for rebellion committed by armed soldiers. Last Monday, December 14th, 2015, Antoine's son Yves Abibou learnt that a judicial committee at France's highest appeals court, the Cour de Cassation, has refused to review his father's trial. The sense of injustice still remains, however, and the campaign on behalf of Antoine Abibou and all the other African troops killed or jailed continues.

Yves Abibou, who lives in France, had not initially taken a close interest in the case. “For 40 years I did not try to find out,” he admitted. However, eventually his private family history came into the public domain through the research of others and Yves Abibou, who has just visited Senegal for the first time since 1975, found himself involved. “We knew there was a demon in our family but we didn't know what,” he said.

The people who helped Yves Abibou unearth his father's past were journalist Raphaël Krafft and historian Armelle Mabon. Antoine Abibou himself had told his “saga” just once, at the end of the 1950s, when his son was still a child.

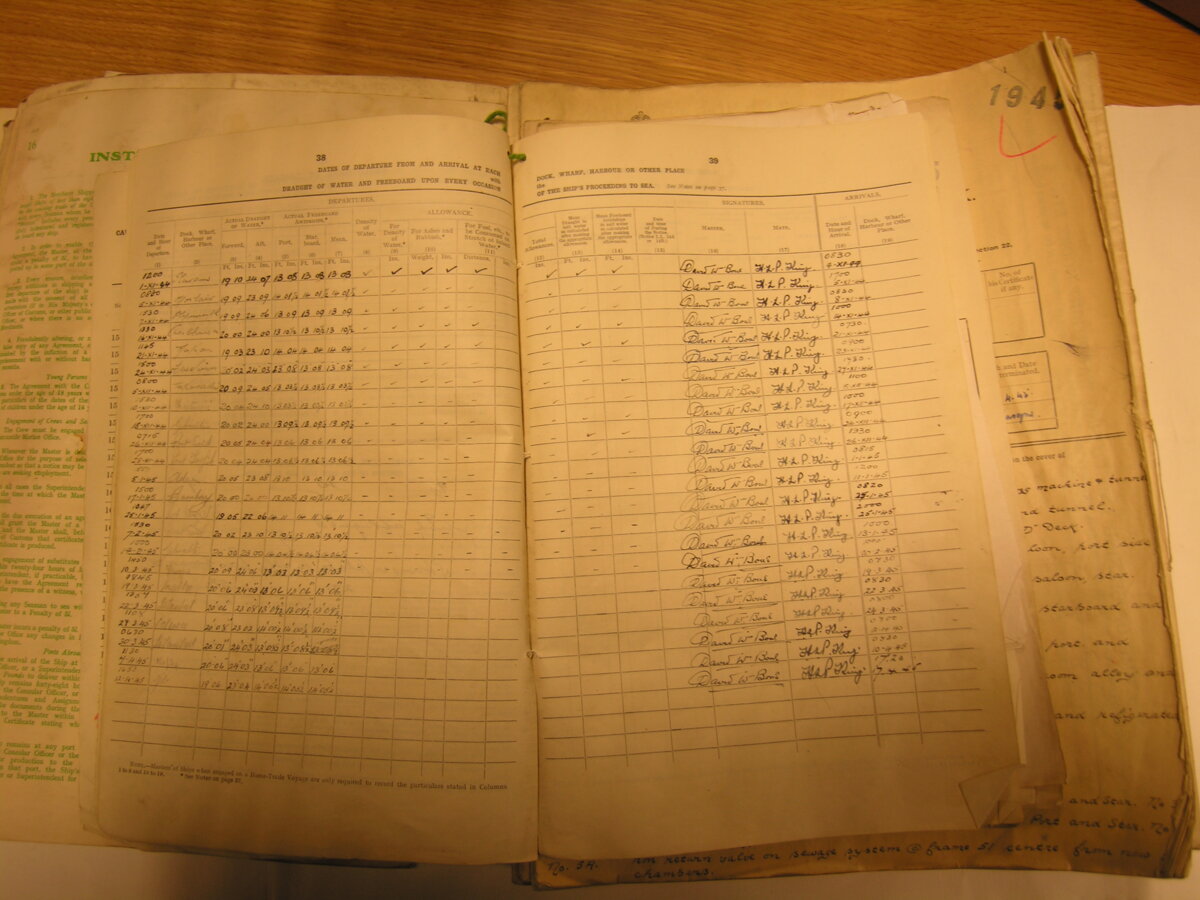

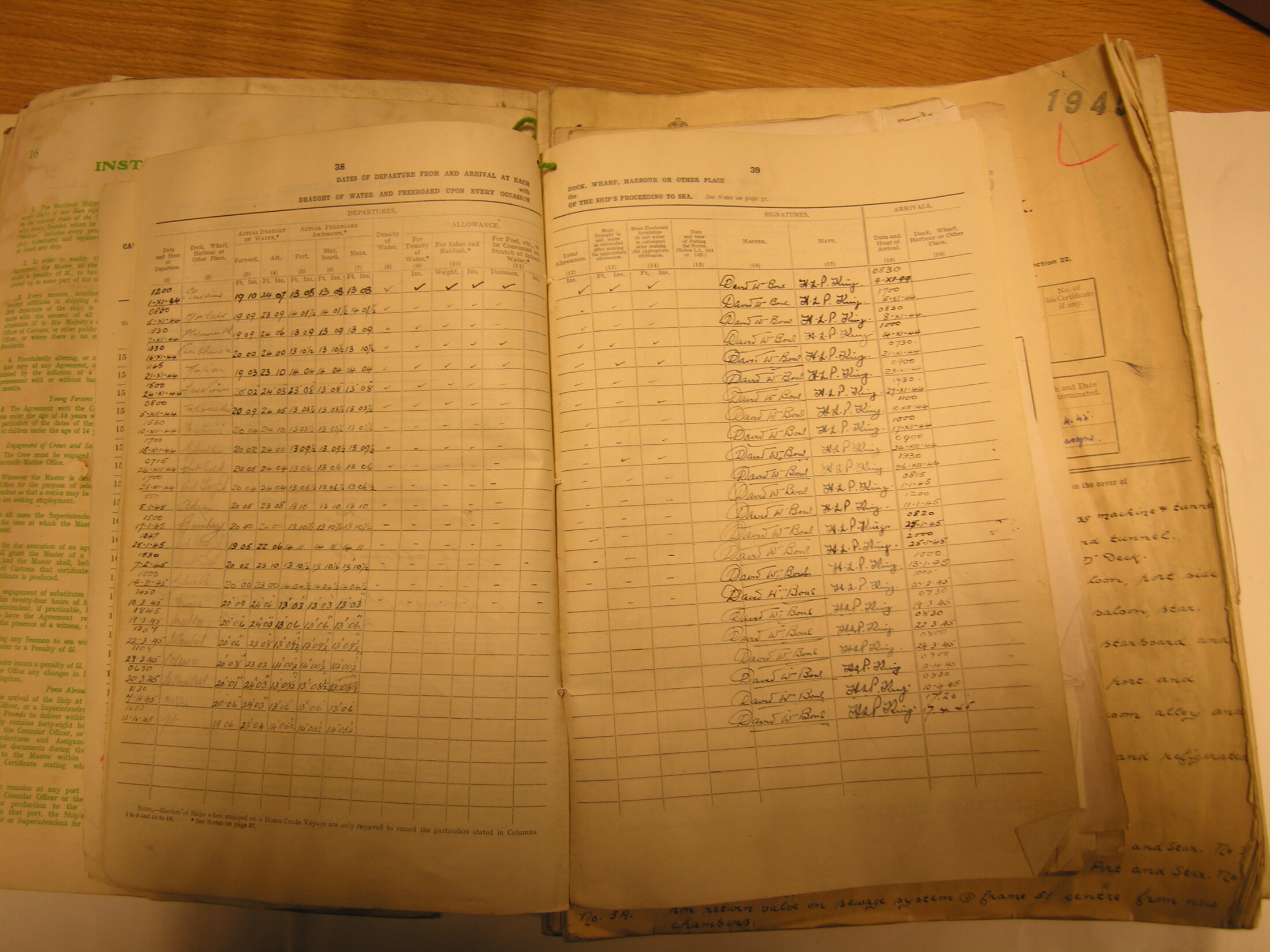

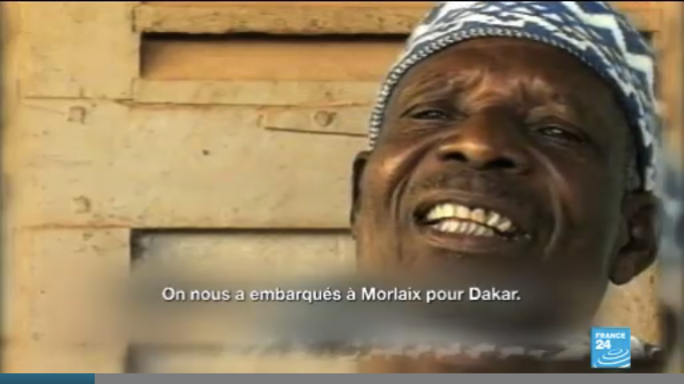

That “saga” goes back to November 5th, 1944 when Antoine Abibou stepped on board the British merchant cruiser HMS Circassia at Morlaix, in Brittany, which was to sail him and many other colonial troops from Senegal, Benin, Sudan and Togo back to Africa. “It was the first contingent of colonial infantry known as 'Senegalese' freed by the Allies or French forces inside [France] to go back to French West Africa,” said Armelle Mabon, who says the soldiers were due to be demobilised. Documentation of the ship's passengers is incomplete but the number of colonial troops on board could have been somewhere between 1,200 to 1,600 according to Mabon's calculations.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The colonial infantry had just come out of four years of captivity in France, detained in German Frontstalags on French soil. Some of the soldiers, including Antoine Abibou, had escaped from camps while others had to wait to be liberated. France owed the troops pay, “a quarter of which [was to be paid] in metropolitan [France], and three-quarters when they disembarked,” at Dakar, according to France's Ministry of war circular n°2080 dated October 21st, 1944.

But once they had arrived in Dakar “the troubles continued” as Yves Abibou says with understatement. Historian Armelle Mabon says that after 15 years of research the “factual knowledge about Thiaroye is now established”. She added: “Though some shadowy areas remain, they don't undermine the general understanding and lesson of this historic event that we can label a massacre.”

The infantrymen were claiming back pay that included a “500 franc combat payment” and a “demobilisation bonus”, according to a report by General Marcel Dagnan, commanding officer of the Senegal-Mauritania Division, dated December 5th, 1944, four days after the killings. The general considered that this detachment of troops was “in a state of rebellion”. The same report shows that Dagnan had received the agreement of his superior officer General Yves de Boisboissel for an intervention on the morning of December 1st, 1944. For this intervention the French Army mobilised “three indigenous companies, an American tank, two half-tracks, three armoured cars, two infantry battalions, a group of French non-commissioned officers and troops”.

So what exactly happened on that morning at Thiaroye? It is known that in the early hours the colonial infantry troops gathered in the main square at the camp. It is accepted that they had done so under orders. According to one version, the troops were hoping that they were at last going to get their pay, and that they had needed little coaxing to turn out on parade. On the other hand, the French authorities insisted that there was a mood of unrest, and that while the colonial infantry may have finally gathered on the square, they did so with weapons in their hands. Shots were fired. But by whom? According to the official military reports their deadly fire was a response to shots coming from the supposed mutineers. “The [French military] company fired more than 500 projectiles at men in groups. It was a killing field,” said lawyer Tamegnon Hazoumé, who pleaded the case in favour of a review of Abibou's trial before the Cour de Cassation.

After the massacre came the arrests. As far as the French authorities were concerned, the mutineers had to be punished, and they included Antoine Abibou. According to the Cour de Cassation's account, Abibou had “steadfastly denied the accusations made against him”. In its ruling the court said: “He indicated that he had got up early and went to the infirmary to be treated for dysentery contracted on the boat on which he had come to Dakar. The doctor had not yet arrived. He had seen several nurses whom he had not spoken to, had laid down on a bench, and had seen several infantrymen with fixed bayonets. Later, some other infantrymen had come to tell him that the men were going to muster.

“He had got up and, having gone via his hut to change his night cap for his woollen balaclava, had helped, at their request, some non-commissioned officers from his group … to assemble the men. He had seen several infantrymen talking with a captain and he had told them: 'Clear off from there. Are you not ashamed to be talking with a captain?' Then he had gone to the square where he had remained until the firing began. He had been arrested after the gathering, though he was sitting at the same place for more than two hours. He had not refused to get up nor to join the group of those who were arrested,” stated the court.

On the other hand, the original indictment had claimed that Antoine Abibou had “refused to obey” orders, had “insulted” a superior and “taken part in a rebellion committed by armed soldiers, numbering at least eight, against the Army”.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Had the colonial infantrymen been paid or not? “No documents [showing] that the repatriated infantrymen's financial claims were illegitimate have emerged,” the Cour de Cassation acknowledged. However it went on to say that “the legitimacy of those claims do no constitute justification that authorises the carrying out of acts of which Antoine X … was found guilty.” Therefore, the judges said “the documents produced by the applicant in his statements in the review, which purport to establish that the repatriated infantrymen had received only a part of the pay that was due to them … are unrelated to the question of culpability”.

Another question is whether the intervention by the French military was premeditated, as could be inferred given the mobilisation in the preceding days of the armoured cars and other infantry battalions. The Cour de Cassation exonerated the camp commanders of suggestions they had wanted to commit a massacre. “The fact, alleged in the statements in the review, that the intervention of December 1st, 1944, was organised with the sole end of carrying out a massacre does not emerge in any of the documents produced in support of the application.”

Had the infantrymen who had gathered in accordance with their orders fired first, provoking the suppression that followed, as the French military has always insisted? “None of the documents produced in support of the application is of a nature as to raise doubts over the testimony or the content of the reports that feature in the case proceedings, which emphasize the existence of a rebellion committed against the armed forces by at least eight armed men,” noted the court. It also dismissed the conflicts between accounts, particularly over the time of the shots, raised by historian Armelle Mabon.

As far as the top French appeal court is concerned there was indeed a “rebellion” on that day. Even though in his speech at the Thiaroye cemetery on November 30th, 2014, President François Hollande did not use this word and instead said he wanted to “repair an injustice and salute the memory of men who wore the French uniform and on whom the French had turned their gun...”

The French head of state's speech was given to commemorate the massacre 70 years after the event, and his words were intended to be conciliatory, attributing the first shots not to the infantrymen but to the authorities at the barracks. Hollande said: “These men [editor's note, the colonial infantrymen] were asking again, once more, one time too many, for the payment of their wages. They received no response. On the morning of the first of December 1944 they gathered on the square at Thiaroye camp and they once again uttered a cry of indignation. Far from calming them and controlling them, the troops in charge of maintaining order opened fire.”

Though the court continues to consider that there was a rebellion, it does not rubber stamp the events that followed, and notes that its ruling should not be considered as “approval of the conditions in which the repatriated infantrymen's rebellion was suppressed”. However, it continued, “it seems that the exact circumstances in which the order to fire was given and carried out, as well as the number of killed and wounded, [all that] has no link with the question of culpability, as in any case this suppression had taken place after the carrying out of the offences [that Antoine Abibou is] accused of, with the exception of the refusal to obey committed at his arrest”. Thus the court ruled that it could not consider reviewing the case.

On March 5th, 20145, Antoine Abibou was sentenced to ten years imprisonment, was reduced in rank and banned from France. He was one of 34 people convicted. They were later granted an amnesty under legislation dated August 16th, 1947, that provided amnesties for various offences committed during World War II, in their case concerning “offences committed in French West Africa in November 1944 by soldiers and former prisoners following mutinies”.

Antoine Abibou's son Yves points out that only declarations made by colonial officers were taken into account by the Cour de Cassation - “as in 1944”. And he said that even their accounts had been considered “superficially”. He continued: “For attentive reading would show the inconsistencies of their statements, probable signs of a fabricated story, which can be compared with the statements of the accused, which are consistent.” Yves Abibou added: “This verdict obviously doesn't give me peace of mind, nor the other children of the infantrymen that I have met in Senegal in recent days.” To his dismay he is so far the only relative to have taken up the case, though he is encouraging others to do the same and he is also “calling on contemporary historians in Senegal to continue with the historical work carried out and to bring this period out into the open”.

Historian Armelle Mabon is also dismayed with the ruling. “The judges relied on official documents that have shown themselves to be misleading but they have not asked themselves any questions and have not taken into account the advances in knowledgethere have been about this historical event,” she says.

No one still knows how many colonial infantrymen were killed at Thiaroye on December 1st, 1944. The official toll is 35, while in his speech President Hollande spoke of 70. It is likely to be many more, as 300 were missing from the roll-call compared with the number of passengers on the Circassia. What is known is that the bodies of the troops gunned down that day were tossed into a mass grave.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter