The US detention camp of Guantánamo Bay in Cuba continues to hold 166 prisoners despite a pledge by President Barack Obama, made during his swearing-in ceremony in January 2009, that the camp was to be closed within one year.

The special envoy who was appointed to empty the camp of its inmates, and to find host countries willing to take those who were officially deemed fit for release, was transferred to another post in early January and his office has now been closed down. Implicitly, Obama’s new administration has quietly sidelined the opportunity to shut this extra-judicial and extra-territorial prison camp.

Meanwhile, European governments, among which several were the first to denounce the policies employed by the George W. Bush administration during its ‘war on terror’, have adopted a similarly silent approach, whereas they could in fact actively help resolve the fate of many of those still held.

Of the 166 prisoners at the base, about 100 are considered by Washington to be eligible for release. These are inmates who the US does not want on its home soil, because they are thought to have committed terrorist acts; nor does it seek to put them on trial, because of the lack of clear-cut proof of their involvement in terrorism.

The problem is that these potentially releasable prisoners have for the most part no country the US is prepared to send them back to, either because some are states from which they could easily slip across borders again, like Yemen, or because others come from states, such as Syria or China, where their lives would be in danger upon their return.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Nabil Hadjarab, 32, is one of those. An Algerian national, he was captured in 2001 in a hospital in the eastern Afghanistan city of Jalalabad, shortly after the fall of the country’s Taliban regime. His lawyers and those close to him argue that the story of his presence in Afghanistan is simply that of a lost young man. The Pentagon believes he was an al-Qaeda member who fought US troops in the country. But both sides agree that he is a small-fry captive who represents little, if any, danger or intelligence interest (see his official case file, as revealed by Wikileaks, here).

For that very reason, the State Department has on two occasions, firstly under the Bush administration then under that of Obama, decided in favour of his release.

But Hadjarab has no wish to return to Algeria, and it is not even certain that the US would approve his transfer to the country. He has previously lived 11 years in France, where he was raised variously by his father, an uncle and a foster family. He has seven half-brothers and sisters, who are all of French nationality. His father and his grandfather served in the French army, as did also one of his half-brothers who was decorated with France’s National Order of Merit.

“Nabil will soon be 33,” said his French lawyer, Joseph Breham. “He has lived for 11 years in France, for 11 years a little everywhere, and for 11 years in Guantánamo.” Cori Crider, the legal affairs director for the British-based NGO Reprieve, dedicated to providing legal support for financially-needy prisoners and which has been particularly active in seeking the release of several detainees in Guantánamo, including Hadjarab, describes him as “the most French” of those who remain in the camp.

Hadjarab’s uncle Ahmed Hadjarab, who lives in the town of Mulhouse, eastern France, has said he is ready to look after his nephew if he were released. Since 2007, the uncle and lawyers acting for Hadjarab have sent a total of 16 letters to successive French presidents Nicolas Sarkozy and François Hollande and their foreign affairs and interior ministers, appealing for help for his release, none of which were ever replied to. Last week they began formal proceedings to request that current interior minister Manuel Valls authorize Hadjarab’s transfer from Gunatanamo to France.

'We will not receive further prisoners'

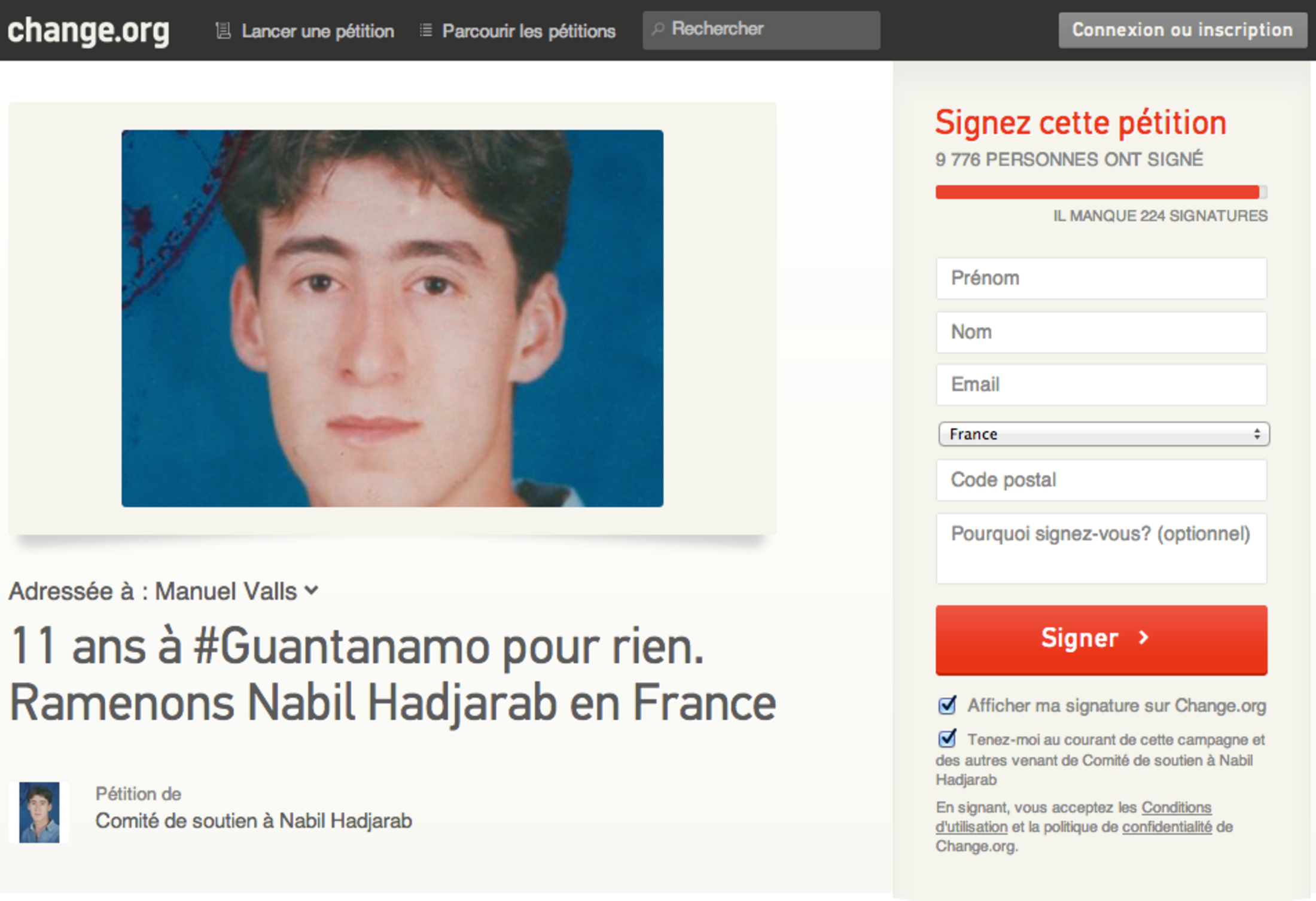

In association with Reprieve, they have also launched an online petition for his release and transfer to France, inspired by the success of a similar campaign that was successful in securing the release and return to Canada of another Guantánamo inmate, Omar Khadr.

French President François Hollande has not spoken in public about the situation of prisoners still detained in Guantánamo since his election to office in May last year, despite numerous precedents of camp inmates who were either returned or sent to France. Between 2004 and 2005 seven French prisoners were returned to France, and in 2009 two Algerians, Lakhdar Boumediene and Saber Lahmar, were transferred to France, where they remain today. The two were captured in Bosnia, where their children continue to live. The two men were the first of Guanatanamo’s inmates to benefit from a habeas corpus procedure before the US justice system which resulted in an order for their release. In negotiations between Washington and Paris, they were allowed to settle in France.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Above: the online petition demanding Nabil Hadjarab release and transfer to France.

Hadjarab’s French lawyer Joseph Breham said the French authorities are guilty of “the crime of inhumanity” in their muteness over his case. “We are the country that hands out good scores and reprimands about human rights the world over,” he added. “And what do we do in this case? The fight against terrorism is also an issue of respect of human rights.”

In the official US case file about him, Hadjarab is described as having spent eight months in an Afghan hostel with links to al-Qaeda, during which time he learned to use a Kalashnikov rifle and, perhaps, explosives. He was wounded during bombing of the Tora Bora mountain cave complex used as a refuge by al-Qaeda and Taliban forces. For Hadjarab’s lawyers, the rest of the file’s contents are conjecture, arguing that information was partly based on confessions given under torture.

In January 2009, under President Nicolas Sarkozy’s administration, the then-spokesmen for the French foreign affairs ministry defined the “case by case” criteria for accepting the transfer to France of inmates released from Guantánamo. “On condition that the persons [concerned] want this, [and] ask for it,” he said. “On condition that there is a risk, that they feel in danger if ever they return to their country of origin, and that it appears complicated for them to remain in the United States. “Finally, the legal and security implications must be closely studied.” Hadjarab’s lawyers argue that he meets all these conditions.

According to a judicial source contacted by Mediapart, interior ministry officials have given tacit approval for Hadjarab’s transfer to France, but the case is blocked by a less favourable view from the foreign affairs ministry and the presidency itself.

“We support the will of the Obama administration to close Guantánamo, but France has already made efforts by receiving two Algerians,” a foreign ministry source, who asked not to be named, told Mediapart. “We will not receive any further prisoners. It is for other European governments to make an effort.”

A source at the presidential office, the Elysée Palace, similarly speaking on condition of anonymity, said: “Hadjarab’s profile poses a problem, he has a background that could present a threat.”

Thus, despite past grand speeches by the French Left denouncing the inhumanity and illegality of Guantánamo, and condemning the questionable methods employed by the US in its anti-terrorist campaigns, it appears unwilling to help put an end to a place of judicial anomaly where suspects endure conditions that tried and sentenced prisoners are never subject to. By adopting this stance, the French authorities have made themselves an accomplice of the US in its continuing activities at Guantánamo Bay.

-------------------------