On Wednesday August 14th, just hours after the Egyptian security forces had begun their bloody crackdown against the supporters of ousted president Mohamed Morsi, President Barack Obama made a short televised intervention from his holiday retreat, then returned to his game of golf. The symbolism was almost overwhelming; the United States is on holiday, please don't disturb it, in any case not for a few hundred deaths at the hands of one of its most faithful allies in recent decades.

The same scenario occurred a week later. Almost exactly one year after the president declared that the use of chemical weapons in Syria would cross a “red line'”and would lead to American retaliation, the Bashar al-Assad regime launched an attack using neurotoxic agents against its own civilian population in the suburbs of Damascus. What was Obama's initial reaction? He remained silent, leaving his spokespeople to declare that the use of chemical weapons had not been fully confirmed and that it should be left to the United Nations on the spot to investigate. It was not until almost a week later, when Syrian government involvement in the outrage could scarcely be denied, that the mood began to change in the White House and the administration declared itself ready to launch a limited and targeted strike against the Syrian regime (1), though even then Obama insisted no final decision to attack had been made.

If some countries and people in the world celebrate this partial withdrawal from the global stage on the part of the Americans, the fact remains that it poses a problem; for international relations abhors a vacuum at the top. The so-called 'hyperpower' of the start of the 21st century – the term was coined by then French foreign minister Hubert Védrine – is no longer 'hyper' and one can even question whether it remains a 'super' power if it does not use the still-formidable artillery at its disposal. In any case, no one was expecting such a disengagement and so many misjudgements from Barack Obama. Foreign policy is on its way to becoming the biggest failure and the greatest disappointment of his two terms in office.

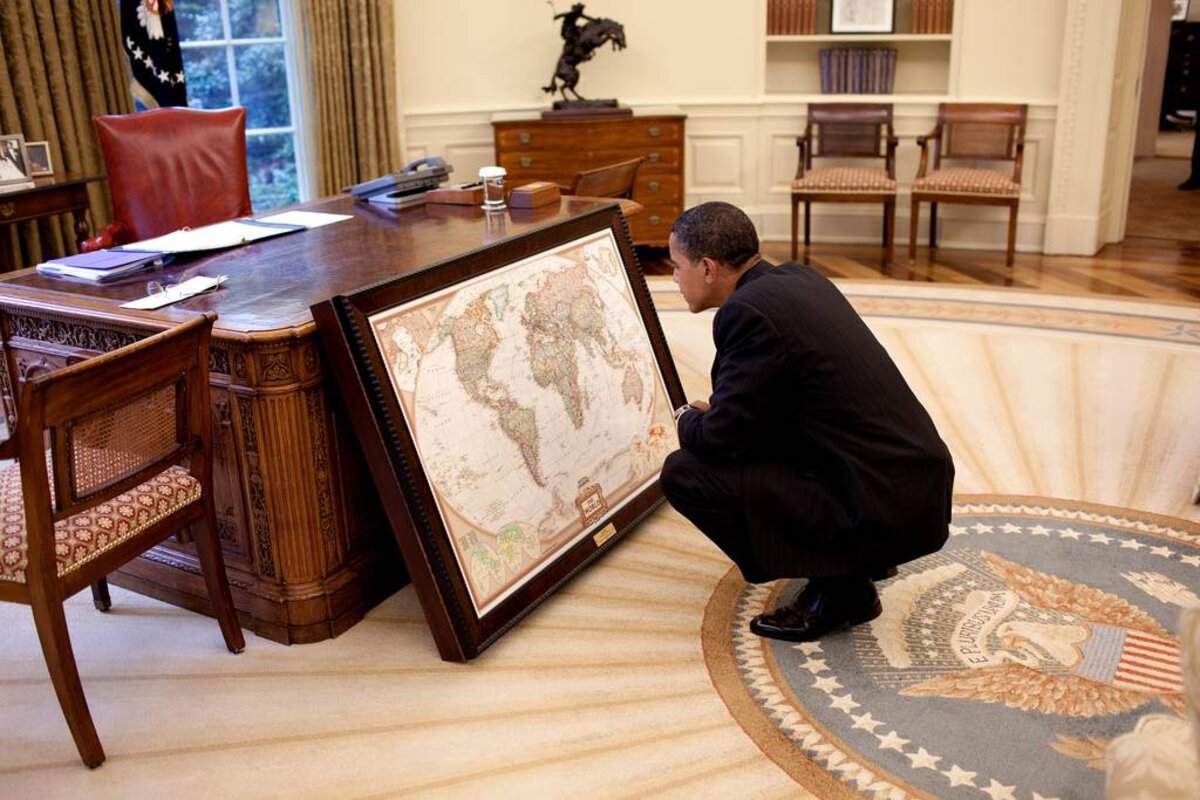

Enlargement : Illustration 1

During his electoral campaign in 2008 Obama was seen as both anti-George W. Bush and, to an extent, anti-Bill Clinton. He had promised to get rid of the security and anti-terrorist obsession of the first, while restoring the United States' image abroad, an image tarnished by actions seen as immoral, unilateral and badly-prepared. He also seemed to want to avoid the endless dithering and 'moral relativism' of the second. Moreover, his Kenyan origins, his travels as a young man and his openness to the world, and even his four years as a senator during which time he was involved in the issue of disarmament, all contrasted favourably with Bush's Texan regionalism and Clinton's narrow-minded Arkansas-honed approach.

Unfortunately...five years after those expectations of a renewal or, at least, those hopes of limiting the damage to the US's reputation, the Obama presidency is slipping slowly towards the status of international insignificance. “Obama may be one of our foremost realpolitik presidents, but you get the sense that he’s just not very good at it,” wrote commentator William Dobson on the Slate website earlier this month. Perhaps in order to distinguish himself from his predecessor, whose first years in office bore the hallmarks of a genuine international relations policy, that of neo-conservativm, the current president treats each crisis and each conflict independently, weighing the pros and the cons depending on the context. That corresponds to the temperament of the dispassionate lawyer that he resembles. But the problem is that Obama's responses range between two categories, each shown to be as ineffective as the other:

1) A great declaration of intent that is not followed up;

2) Procrastination.

In each case one arrives at the same conclusion. “The United States has gone from being a hyperpower to becoming the equivalent of a mere commentator on world affairs,” writes David Rothkopf, Editor-at-Large of the influential Foreign Policy magazine.

-------------------------------------

1. The mood in Washington changed on Monday August 26th, three days after the initial publication of this article in French, when Obama's Secretary of State John Kerry said the regime's use of chemical weapons was now “undeniable” and a “moral obscenity”. US intelligence reports had by then clearly established that the weapons had been used by regime supporters and not the rebels. Even so, there was still a clear reluctance on the part of Obama to intervene. David Rothkopf of Foreign Policy magazine, who is quoted elsewhere in this article, said of the administration’s change of tone: “I think they feel they have no alternative but to respond, if for no other reason than that the president himself defined this ‘red line’ over chemical weapons, and has allowed them to cross it a few times already...There is clearly no appetite in the US or among its allies to get involved in a protracted conflict in Syria but if he did nothing now, [Mr Obama’s] credibility in the Middle East would fall to zero.” See also Rothkopf's article 'Too little, too late'.

How Obama's foreign policy has performed

Here is a brief review of the American response to different crisis points on the planet

Syria

The American approach is clearly not the only one open to question, as France and Britain find themselves in the same position, largely because of the previous intervention in Libya, which irritated Russia and knocked over a few unexpected dominoes, for example Mali. Nonetheless, Obama became entangled in it himself by establishing a “red line” over chemical actions, effectively pledging action if they were used. Did he perhaps imagine that the Assad regime would never dare to use these weapons of mass destruction? In which case he was certainly naïve or badly informed about the very nature of the regime; we should not forget that another Ba'athist regime, that of Saddam Hussein, gassed its Kurd population at the end of the 1980s. Now Obama is trapped and has had to react; to do otherwise would have reduced the United States to the status of a paper tiger.

Now that the Syrian rebellion is fragmented and the jihadists are more or less in the majority, there is no longer really a “good” camp to support, as the American chairman of the joint chiefs of staff General Martin Dempsey recognised recently when giving evidence to Congress. But that was not the situation two-and-a-half years ago, when the revolt began, nor even just a year ago. As a disillusioned British diplomat notes: “What's terrible is not that the United States did not succeed in stopping the massacres in Syria, but that they didn't even try!”

During an interview at the beginning of January, designed to explain his wait-and-see approach, Obama launched into a long tirade that was in effect an admission of powerlessness, at the end of which he posed the question: “...how do I weigh tens of thousands who've been killed in Syria versus the tens of thousands who are currently being killed in the Congo?”

The sub-text is clear: why intervene in Syria and not in the Democratic Republic of Congo? This is Clintonian moral relativism in all its glory, combined with the crudest kind of political realism.

Egypt

If there is an Egyptian policy in the United States, no one understands it. Having negotiated the departure of Hosni Mubarak quite well, in other words having let go of this old ally just in time, the White House then kept sending out contradictory signals, supporting the Muslim Brotherhood, the army and the liberal opposition in turn, finally managing to lose its credibility with all three. By refusing to call the military takeover in early July a coup d'État, so that under US law he did not have to cut his country's 1.5 billion dollar annual aid to Egypt, the president made himself look ridiculous. Then in showing himself incapable of deciding if he should continue with the aid or cancel it, the president simply showed his indecision, and thus America's impotence. The Egyptian army, like the Assad regime, calculated that provoking the Americans would have no negative consequences – and they are in the process of winning that bet.

Iran

When he came to power Barack Obama made a gesture towards the Iranians by sending them a personal message of friendship. This was never followed up. During the major post-election demonstrations in Tehran in 2009 the White House remained silent. Following the archaic line of the US Congress – which is itself influenced by the Israeli line – the policy towards Iran has remained marked by barbed remarks and sanctions, as if Iran's nuclear programme is the only issue when it comes to entering a dialogue.

Iraq and Afghanistan

The two countries invaded by the US under the Bush administration are today both headed by leaders who have terrible relations with Washington, even though the US helped install them in power. Despite an American request not to do it, the Iraqi prime minister Nouri Al-Maliki opened the country's airspace to the Iranians so they could send arms to help their allies in Damascus. As for the Afghan leader, Hamid Karzai, he has continued his work of undermining US policy, without attracting anything more than some tellings-off from American officials.

In regions and countries that have not been hot spots, but with which Obama had promised to establish better relations or a fresh start, the outcome has not been any better:

Asia

The recent nomination of Caroline Kennedy – the daughter of JFK – to be US ambassador to Japan is characteristic of the American attitude towards the East. In 2010 the Obama administration initiated its “pivot” to Asia strategy, in other words shifting American focus towards the most populated part of the world. And yet when it came to naming one of his key ambassadors to put in place this policy, Obama chose someone with no knowledge of the region, nor any diplomatic or commercial experience. The absence of strong relations with India, the constant petty trials of strength with China and the tensions with Pakistan mean that the “pivot” has not become a reality of US foreign policy.

Russia

The cancellation of a planned US-Russian summit, which was scheduled in Moscow for the beginning of September, was as much the result of a fit of pique as the fear of confronting the Russian president Vladimir Putin on his home turf. No US-Russia summit was cancelled during the Cold War, when the stakes were rather more important that the asylum granted to whistleblower Edward Snowden. Vladimir Putin is certainly a detestable and inflexible person, but not wanting to meet him comes across as an American capitulation. Here, once again, Obama is giving up on thorny issues with Russia (for example Syria, gay rights, democratic freedoms and so on...) without even trying to tackle them man to man. This can only strengthen Putin's hand.

Latin America

Every now and again the United States announces that it is going to start on a new footing with its neighbours to the south and encourage friendlier relations. And each time nothing happens. Focal points that are outdated (Cuba, Venezuela) or unilateral (war on the drugs trade) still dominate the Washington agenda to the detriment of creating more imaginative partnerships with Latin American countries. The inability of the United States to accept Brazil for what she is, that is to say an indisputable political and economic major player on the continent, is quite simply political blindness. The simple fact that the countries in the world that have considered giving asylum to Snowden (Venezuela, Nicaragua, Ecuador and Bolivia) are all near neighbours should, however, seriously make the White House question itself.

Israel-Palestine

The new Secretary of State John Kerry has begun yet another American initiative using its mediation to remove, if not the entire Israeli-Palenstinain conflict, then a least the deadlock that has gripped the issue in recent years. But even if it is successful – which is far from being a given – progress in this area will have nothing like the impact it would have had in the past. This conflict has now become relatively minor compared with other tensions in the Middle East, those caused by the 'Arab Spring', the existence of the so-called 'Shia crescent' and the emancipation of the emirate states on the Arabian Peninsula. Some analysts wonder whether the efforts used by John Kerry on this issue are worth the trouble in relation to the other crises. At the same time this could be Obama's joker card; if he succeeds in getting a new type of Oslo Accord, then his other failures could be forgotten.

Strange foreign policy bedfellows

The nature of the American government system – and the way media coverage works – means that all decisions converge on the White House. And under Obama foreign policy is controlled from the Oval Office to an unprecedented extent. In the current administration there is no equivalent to the Cheney-Rumsfeld-Wolfowitz axis (vice-president, defence secretary and deputy defence secretary respectively) under Bush, no Warren Christopher, Madeleine Albright, James Baker, Zbigniew Brzezinski or Henry Kissinger.

According to one senior American official there are today ten times the number of foreign policy advisers at the White House than there were 40 years ago under President Richard Nixon. This centralisation is in keeping with the president’s own personality. According to all biographies of him, Obama is a man who likes to decide on his own and who is often convinced that he is the most intelligent person in the room. This kind of isolation and superiority increases the likelihood of procrastination and misjudgements in the face of complex situations. It turns out that it is much easier to make great declarations of principle – which sometimes turn into curses – than to get to the heart of problems. Or, as David Rothkopk said, to comment rather than to do.

When he arrived at the White House Obama knew that he was inheriting a country that was suffering from a catastrophic international image. He tried to change this through some beautiful and noble speeches (such as the one in Cairo in 2009) or by relying on his own personal story. In view of the level of trust that he benefited from in 2008 from all four corners of the planet, he could undoubtedly have achieved this – if he had not just been content with words. But then, because it was doubtless easier to do nothing (lack of courage), and perhaps also because he had not given sufficient attention to the consequences of his actions (isolation), he was not able to restore the moral prestige that the United States has often enjoyed.

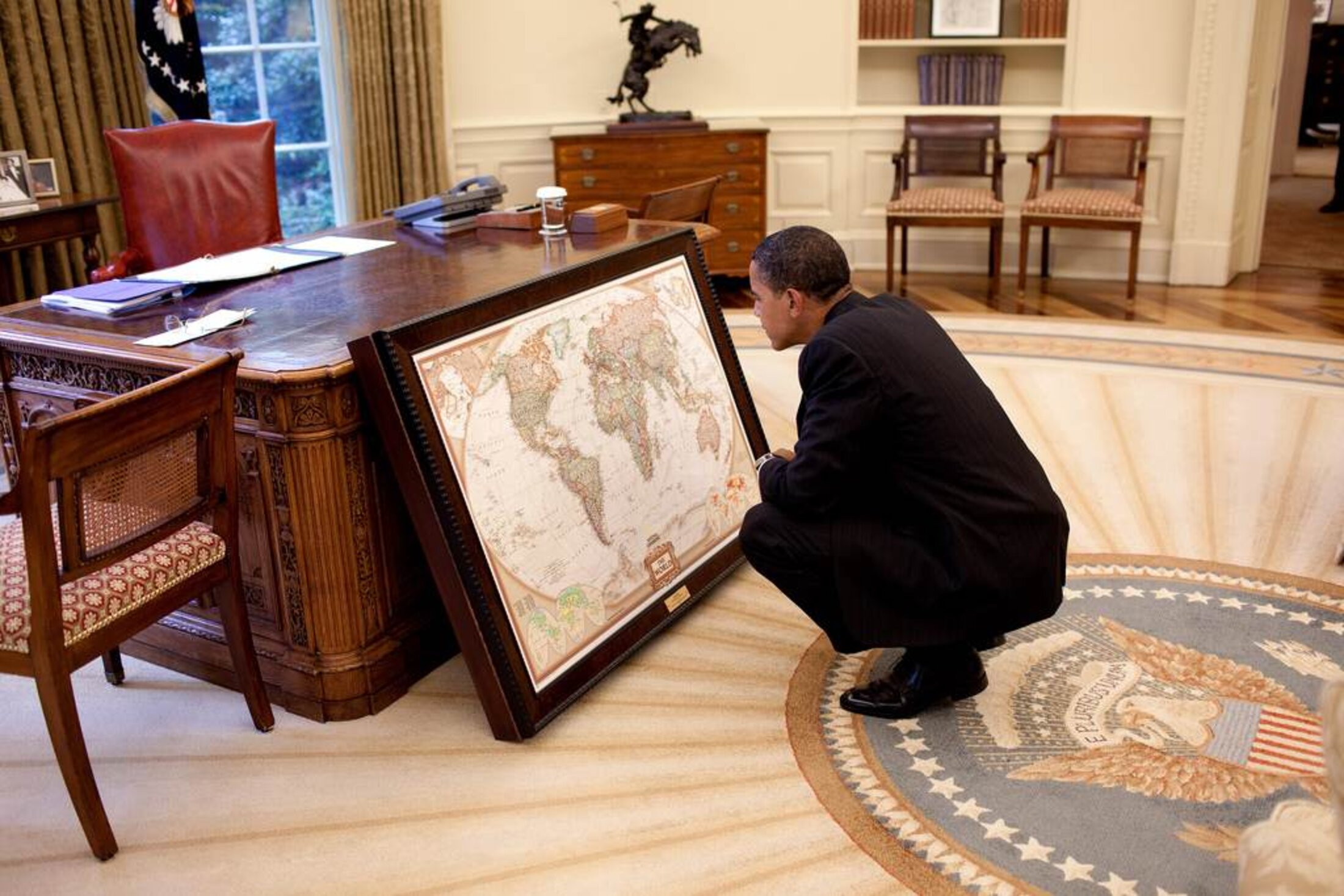

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The failure to close the detention camp at Guantanamo, despite Obama's promises to do so, and the massive use of unmanned drone aircraft, without being willing to recognise the civilian victims that they cause, are two emblematic issues. The continuance of Bush-like policies in the fight against terrorism is another. And then the relentless fight against the messenger, whether this concerns eavesdropping on and searching the premises of journalists, or against whistleblowers (Bradley Manning and Edward Snowden) brought to light the vindictive excesses of a government that cannot bear to see its little secrets revealed.

How can one admonish Putin or the Egyptian generals for imprisoning journalists who are doing their job, when the US Department of Justice does the same thing when it believes US interests are in danger? How can one urge the Chinese to stop monitoring the internet when the American government has the keys to the door at Microsoft, Google or Yahoo!?

Because of who he was and the enthusiasm that accompanied him, Barack Obama had a golden opportunity to help his country to regain a moral position that it had lost. He did not do so. But, there again, this was not because he failed in the attempt, but because he did not seriously try.

Faced with these many difficulties, and on domestic issues too, the US president has a tendency to blame Washington inertia and the endless and paralysing fight between Republicans and Democrats. While it is true that the system has become debilitating, that is not always the case on foreign policy – as George W. Bush proved. Today, in the wake of the Egyptian and Syrian crises, we can see two coalitions taking shape. The first contains the isolationists, who are recruited both from Republicans who prefer to put “America first” and from among Democrats who mistrust any foreign adventure that resembles neocolonialism. The second group includes the left of the Democrat Party, those who defend the universality of human rights and certain 'liberal' values, allied with what remains of the neo-cons who think that the United States is an exceptional power that has a positive role to play in the world. It is scarcely exaggerating to say that the left of the Left in the US finds itself alongside the political inheritors of George W. Bush, ranged against the centrists from Left and Right.

Confronted with this demarcation line, Obama has his feet firmly in the centrists' camp. Without doubt it suits his real nature – contrary to what he had let people believe during the 2008 campaign. But he cannot use this positioning as a fatalistic argument to say “there is no alternative”, because there is clearly an alternative domestic coalition that would allow him to adopt different positions, less wait-and-see and more interventionist, if he wanted.

Because of its military, economic and cultural power the United States remains the principal point of reference in the world. It is the country to which the world's gaze turns when there is a crisis. The divisions in Europe, Chinese isolationism, the still understated ambitions of Russia, all ensure it is still the leader on the international stage, in spite of everything. But Obama does not seem ready to shoulder this role, as his hesitations following the chemical attack in Syria have once more demonstrated. Perhaps this is because he does not believe in it, but more clearly because he has shown himself to be incapable of doing so. In foreign policy, as on domestic issues, he shows a clear lack of courage. He thus leaves the impression that the United States is withdrawing into itself and taking a holiday from the rest of the world.

------------------------------------------

English version by Michael Streeter