Two days before Christmas, an evening train from the Italian town of Ventimiglia, which lies close to the border with France, travelling west to the nearby French Riviera city of Nice hit a group of migrants following the rail lines towards France, killing an unidentified young man. The rest of the group fled before emergency services and the railway police arrived.

According to Italian daily La Repubblica, the victim was an Algerian aged 25. It was the fifth accident involving migrants on the line running between France and Ventimiglia since August 2016, but the first in which a migrant was killed. The train driver suffered from psychological trauma that led to him being signed off work.

The macabre series began last August 5th when a 27-year-old Sudanese man was seriously injured by a French train in the last tunnel on the Italian side of the border. He was taken by helicopter to San Martino hospital in Genoa, suffering from a head injury. The train driver said he saw three people on the rail lines as he approached the border post, and his train hit one of them. By the time emergency services arrived the two others had disappeared.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

On the night of October 1st a French train driver felt an impact just before Menton-Garavan, the first station on the French side of the border coming from Italy. The driver searched the rails and saw several people running away, but did not find a body or anyone injured.

SNCF, the French railway operator, has a clearly laid-down procedure for accidents involving people on railway lines. The driver must stop, get down and inspect the rails, then alert the control centre, which halts rail traffic so that the police and emergency services can safely intervene.

The Ventimiglia-Nice line has become the bane of drivers, according to Cyrille Poggi, the CGT trade union representative for drivers in the region. "They are traumatised because there are a lot of corporal accidents because of the refugees in the tunnels," he said. "The line is winding, with unlit tunnels and poor visibility. A train needs 300 to 800 metres to stop. Metal wheels on metal rails, they brake very poorly. Often the accidents happen at night. The refugees pass through in a group and we do not find the bodies."

Under SNCF rules another driver has to take over from the first driver in the case of an accident, which Poggi said has consequences on productivity for the rail operator. "That is why management wants to re-introduce the whistle in the tunnels," he claimed.

A ticket inspector said drivers had adopted the habit of hooting in the tunnels on their own initiative, "because this has been going on for years". There was always the risk of hitting people, said the inspector, who, like most of those SNCF employees interviewed for this report, asked for his name to be withheld. "The drivers above all are under stress when they enter the tunnels. On each journey we see people, either very early or at the end of the day."

The phenomenon goes back to the Arab Spring of 2011, which turned Ventimiglia into a gateway into France for thousands of Tunisians. However, another driver, who has worked for the SNCF since 1998, speaking on condition his name was withheld, recalled having always heard of accidents with migrants in the area. "At the time we called them illegals, but today it has grown," he said.

"It’s very dangerous," the driver added. "They walk in the middle of the rails on the sleepers because it's easier than on the edges where it slopes and there are stones. They are not used to the speed of our trains. And they also do not know, just like many French people, that you do not hear a train coming, and that it doesn’t stop in a few minutes."

Two railway lines link Ventimiglia to France, one via the coast through the small town of Menton at the French border and on to Nice, and the other through the rugged coastal lower Alps and Roya Valley. France reinstated border controls here in November 2015 following the Paris terrorist attacks, and since then SNCF employees on both lines see migrants every day, walking along the rails to avoid police checks on trains. "Before, lots of migrants came through Menton, Sospel and Tende,” said a ticket office clerk. “Now we don't see them any more at ticket offices, they walk along the rails."

It happens that some get lost and find themselves near stations. "When we go to pick up the carriages for the first train to Breil-sur-Roya, we sometimes trip over someone who slept outdoors near the carriages," said another driver who asked not to be named. "It is getting really cold, there are going to be dramatic incidents."

One evening late last September, an SNCF employee found a young, "frightened and hungry" migrant on the platform at Breil-sur-Roya, a town in the coastal Alps near the Italian border. He let the "kid" stay overnight in the local SNCF depot then hid him in the driver's cabin on the first train for Nice.

Migrants trying to cross without being checked also hide under seats or in the trailing locomotive when the driver has forgotten to close the window. "On the line coming from Breil-sur-Roya you feel the distress. Some of them are 14 or 15," said the ticket inspector. "They hide in dangerous areas – the electric control panels, the motor blowers, the equipment cupboards. It's no longer manageable."

On December 21st, just two days before the fatal accident, two young Nigerian migrants hiding on the train for Nice were rescued by Italian rail police before the train left Ventimiglia. They heard faint knocking coming from an electrical cabinet, according to Italian press reports.

Inside the tiny space were two young men, one of whom had fainted, while the other was exhausted and very weak. A people smuggler had charged them 150 euros to get to France and had locked them in the cabinet. "All the smugglers have the kind of keys that open cabins and cabinets," an SNCF employee said.

Several SNCF employees are refusing to take part in anti-migrant actions and denounce an ambiguous attitude on the part of SNCF. "We are fighting to stop the SNCF collaborating with the witch hunt against migrants," said Najim Abdelkader, secretary of the CGT rail union for Nice. "Unfortunately, the SNCF has given the prefecture [editor's note: police services] access to premises at Menton-Garavan to turn back refugees. And in the trains, CRS [crowd-control police] search technical equipment cabinets and toilets, which means that the SNCF has given them our keys."

Contacted by Mediapart, the SNCF did not respond to our request for an interview on the issues raised in this report.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

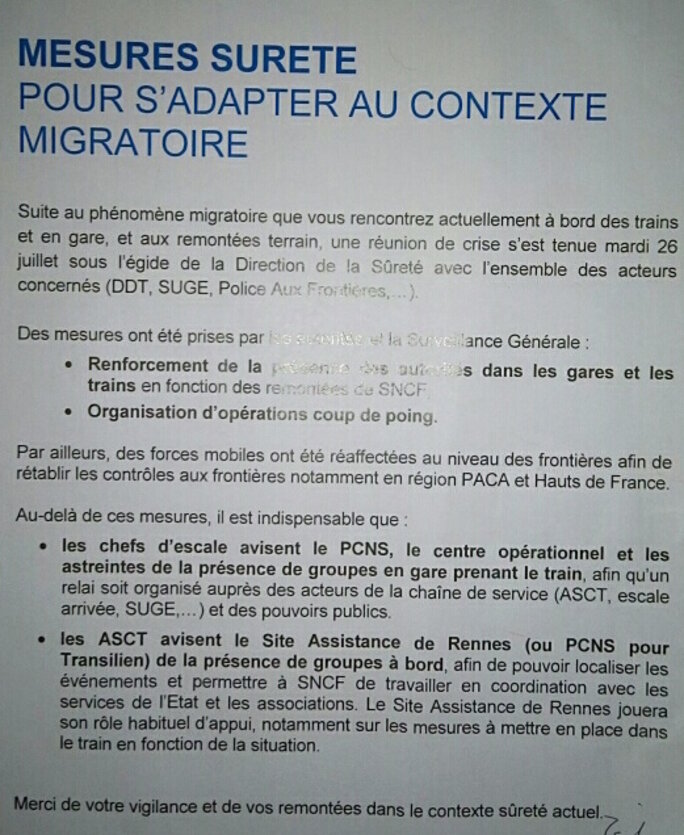

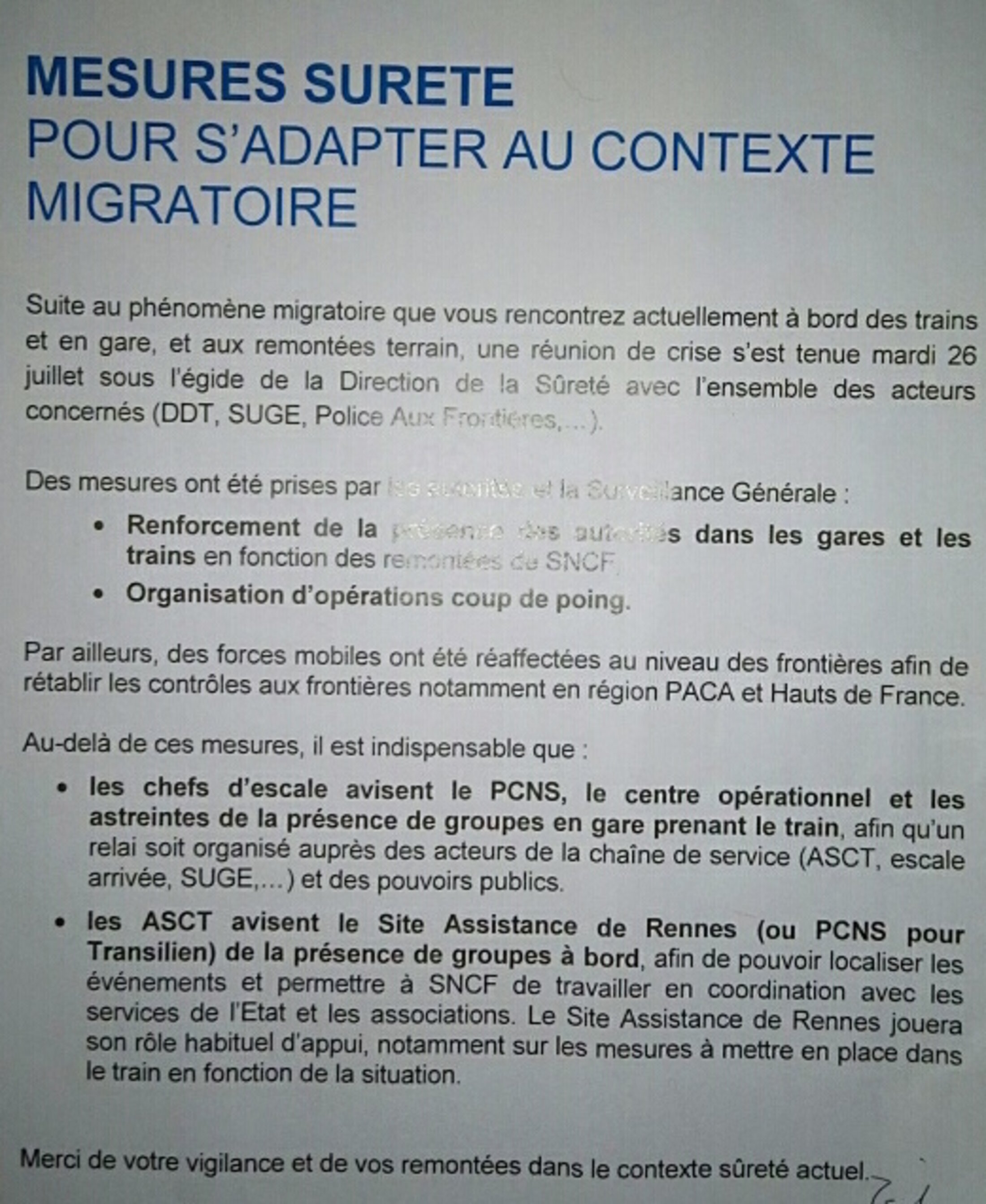

Mediapart obtained an undated SNCF internal memorandum (see above) entitled "Security measures to adapt to the migration context" which is circulated in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur (PACA) region which includes the border area in question. It calls on station managers and ticket inspectors to report the presence of "groups in stations catching the train", or “onboard”, to the rail operator's National Security Command Post (PCNS) "to be able to localise events and allow the SNCF to work in coordination with public services and associations".

The memorandum also says that a crisis meeting was held on the issue on July 26th between the SNCF's security division, the department of the environment ministry responsible for local development, the railway police and the border police. It decided to "increase the presence of the authorities in stations and on trains in relation to requests from SNCF", and the "organisation of lightning operations". The approach goes beyond the government-owned rail operator's main mission, outlined in a law of August 4th 2014, as contributing to "a railway public service and to national solidarity as well as to the development of rail transport, within a context of sustainable development".

“We’re asked to indicate every group of migrants, that’s informing,” said a ticket inspector assigned to the PACA region, who asked for his name to be withheld. According to French law, it is only in a case of ticket fraud that an inspector can ask for an ID document. If the person who has committed the fraud has no proof of identity, inspectors can inform a police officer and prevent the person from leaving until the officer has arrived. Many of the migrants arriving from Italy have tickets, and a number of ticket inspectors say that they have no reason therefore to ask them for ID, and even less reason to inform the National Security Command Post of their presence. “We don’t use racial profiling,” said union official Najim Abdelkader. “It’s not a case of ‘ah, there are two black people, we’re going to ask for their tickets’. It’s when we carry out a check of all the train that we might eventually come across them.”

At Menton-Garavan, the first station on the French side, the CRS and gendarmerie crowd-control squads are present on the premises from when the first train passes through, at 5a.m., until the last, at midnight. Abdelkader said he was angry that when, in 2011, his CGT union had asked for a police presence there to deal with a series of assaults, there was no follow up. “And today the authorities find an incalculable number of CRS to chase refugees out of our country,” he complained.

To assist the police operations, the SNCF has modified the timetables of the trains, lengthening the time of their halt in the Menton-Garavan station, and introducing a halt at the station for the high-speed, long-distance TGV train that comes from Ventimiglia. The police searches for migrants continue to be carried out by discriminate profiling, despite a ruling in November 2016 by France’s highest appeals court, the Cour de Cassation, which made clear that “an identity check based on physical characteristics associated with a real or supposed origin, without any prior objective justification, is discriminatory”, adding that such practices are “a serious error which engages the responsibility of the State”.

It is physically impossible for the CRS and gendarmes to check, in just a few minutes, all the passengers on board trains stopping at train Menton-Garavan, who generally average 60 on trains running the local route, but who can number three times that on Fridays, when Ventimiglia holds its weekly market. “The CRS rarely ask everyone for their ID cards, it’s racial profiling,” said Nadjim Abdelkader. “At Ventimiglia, the French-Italian [police] patrols filter [people] on the platform. They only allow white-skinned passengers to climb aboard and ask the dark-skinned their ID papers.” Abdelkader, whose family is of North African origin, said he had himself been asked for his ID when he was riding a train without his SNCF uniform when accompanying a group undergoing exams to become ticket inspectors. “At Menton-Garavan a police officer asked for my ID documents, not from those surrounding me,” he said.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

“Even colleagues in uniform, Arab or black, are checked,” recounted Cyrille Poggi, the CGT union official who represents train drivers in the region. “Sometimes, the police carry out checks on known guys, just to make them feel that they’re not welcome. The fact that this situation continues, that it becomes banal, removes the barriers for the police forces.”

Poggi and a ticket inspector said the police ask SNCF employees for help in their hunt for migrants. “The gendarmes asked me ‘have you seen any?' I stay neutral because, after a while, you have the impression of being an informer. Those people are trying to escape a country at war.”

“It’s become commonplace,” said a railwayman who, like the inspector, requested his name is withheld. “We know that at Ventimiglia the Italian and French police will screen passengers and that at Menton-Garavan the CRS will search the train and when they’ve finished they give us the authorization to continue on. What can you do? Our management has made it clear to us that we mustn’t ferry people across and that we run the risk of penalties. Especially because we’re in a region governed by the Right and that is apparent among the railwaymen. There are some employees who are keen informers. A railwayman is a citizen like any other, he watches [popular TV channel] TF1 and has problems with purchasing power.”

Sometimes, it is the passengers who denounce suspected migrants. “Occasionally it turns against them,” said a train driver. « It happened once with me that a passenger called the CRS, telling them that some [migrants] were still hiding [on the train], that he had worked in Africa and knew that they were thieves, that they came to France to sell drugs, and so on. The CRS officer asked him by what right he was doing that, how did he know that they were illegals, and asked him for his ID. He ended up on the platform, because the ticket inspector noticed that he didn’t have a ticket and told him to get off.”

But there are times when the police searches turn violent. Cyrille Poggi said he was involved in an incident at Sospel, a village about 30 kilometres north of Menton. “There were many refugees in the train, and the two gendarmes wanted me to close the doors,” he recounted. “They wanted to blosk the refugees in the train while waiting for reinforcements. But it’s not our job. I refused. They called the SNCF Command Post to change the signals and stop me leaving. The refugees wearing trainers ran away. Those in flip-flops or who were barefooted remained stuck. A gendarme used his Taser. The senior officer, at his nerves’ end, shouted out the standard warnings and I thought he was going to fire [his service weapon]. But the refugees weren’t threatening. It was the opposite, they wanted to run off.”

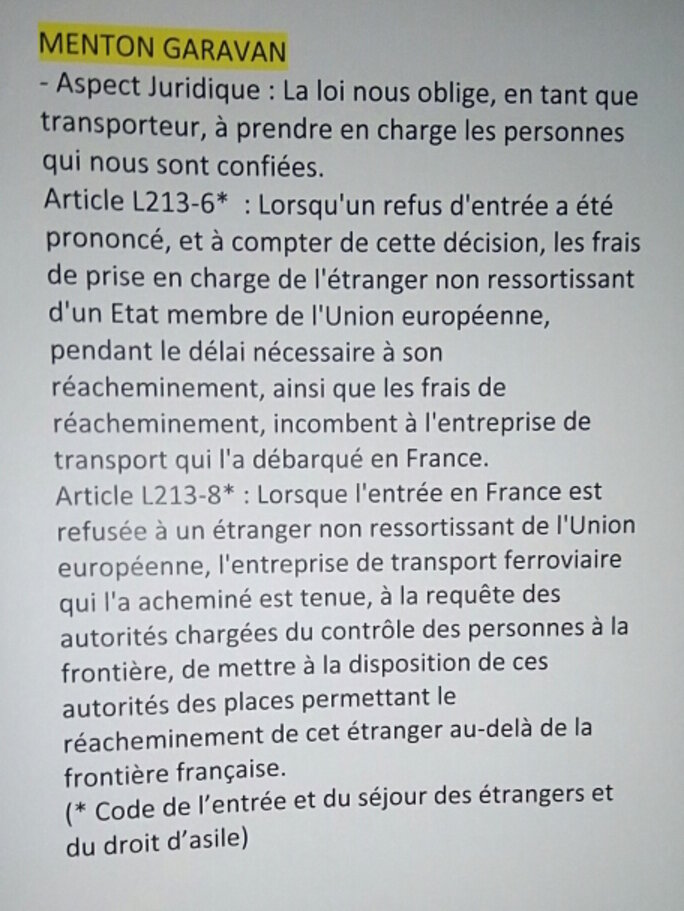

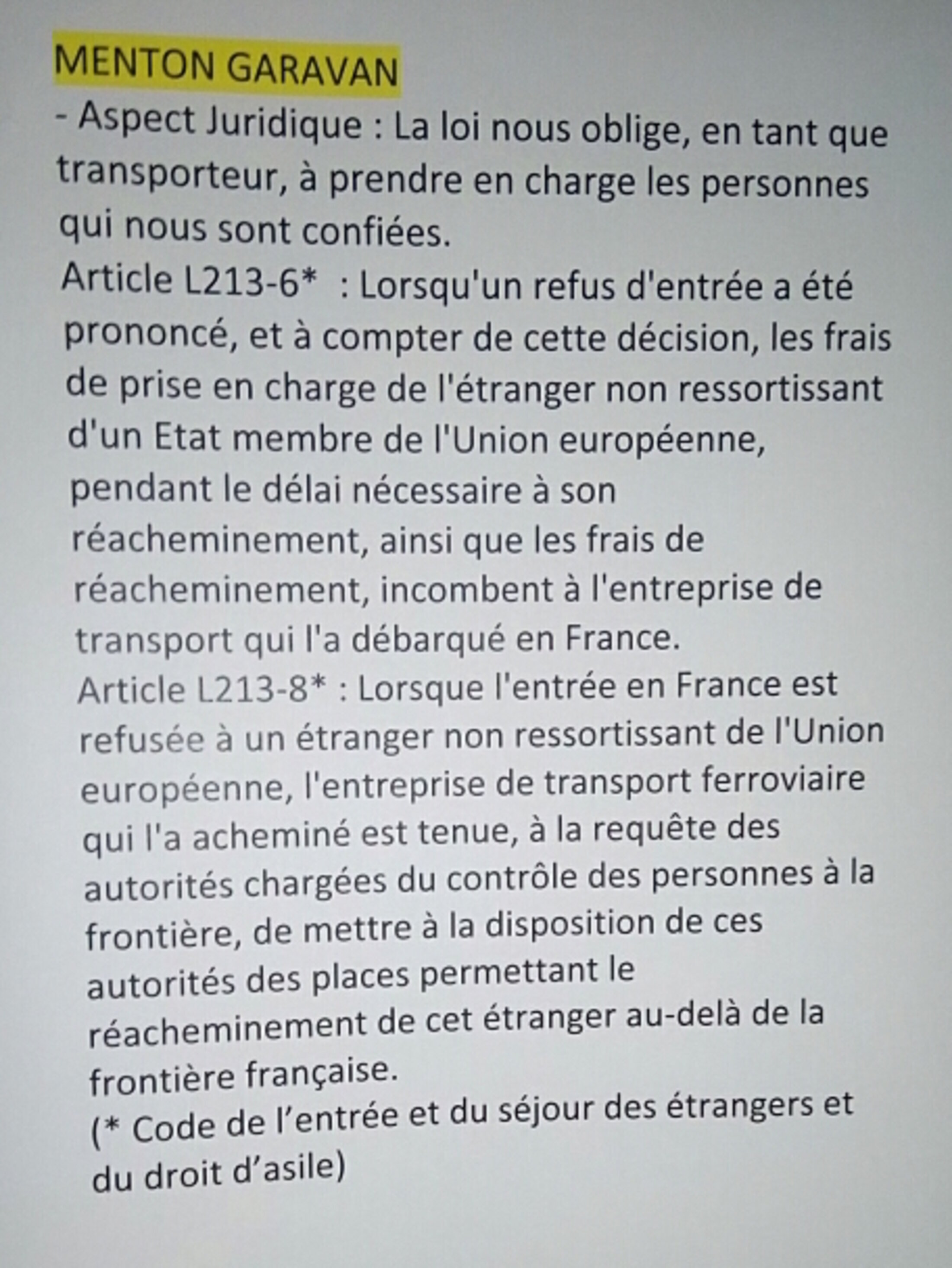

Migrants held by the police at Menton-Garavan are sent back across the border to Italy by train: the detained are put on the last train to Ventimiglia, in groups of 30, without tickets or any other formalities. At Nice central station, the SNCF has posted a notice (see below) in the ticket inspectors’ staff room which underlines the legal requirement that transporters must “take charge of those persons who are entrusted to us”. Under French law, when a foreign national from a non-European Union member state is refused entry to France “the railway company who transported him is required, on request of the authorities […] to place at the disposition of the said authorities seats to allow the transport of the foreign national beyond the French border”.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

“It often involves families with infants who end up sleeping in the station at Ventimiglia,” said Najim Abdelkader. More and more drivers are refusing to take them, which has caused a few altercations between the bravest and the CRS.” Another driver, whose name is withheld, spoke of one such incident: “In September, at Menton-Garavan, travelling in the direction of Vintimmille from Nice, five CRS tried to hand over to me a group of about 15 migrants, of who at least ten were minors. I refused, because they were minors on their own. The CRS told me their parents were there. I asked for documents to prove that. I got my train to leave. On the return leg, the CRS, edgy, were waiting for me. They got out their mobile phones and took photos of me, and film. ‘Who gave you authorization to leave?’. These methods, it reminds me of 1939-45.”

According to French law, the police must take charge of any unaccompanied minor in such a situation and subsequently placed in a children’s social aid centre (ASE) sited in the département (county) concerned. But the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes département, which oversees the application of regulations in the area surrounding the border with Italy, refuses to enact this provision, citing the recent re-introduction of border controls following the massive arrival of migrants in Europe (France is a member of the Schengen Area of EU countries which, in normal conditions, enforce no systematic border controls). The prefecture maintains that whenever migrant minors are subject to police intervention at any of the 13 authorised border crossings in the Alpes-Maritime département, which includes the railway stations at Menton-Garavan and Sospel, they are considered as not having been admitted into France, and therefore have not entered the territory.

Once a migrant has successfully passed the station at Menton-Garavan, the police checks in France become random. Some migrants make it to Cannes, others to Marseille, 180 kilometres further west, where they can be seen, at the city’s Saint-Charles station, mulling around in small groups with no luggage. There, those with lesser funds choose to continue their journey by long-distance coach.

In the TGV [high-speed train] for Paris, most of the refugees have tickets, sometimes in 1st Class costing 180 euros when the 2nd class is full up,” said union official Najim Abdelkader. “If they don’t have a ticket we [ticket inspectors] try to obtain their identity. They sometimes have letters from [migrant aid] associations asking for the inspectors to be charitable towards them.” If a migrant has no ID to show, the inspectors are required to alert the police, who would board the train at the next stop or wait for them on arrival in Paris, but with resources stretched by the current state of emergency declared in France to counter terrorism threats, the police do not intervene. “Most of the ticket inspectors don’t [alert the police], there’s more a show of solidarity than a manhunt,” said Abdelkader. “Often our colleagues in the TGV hand out a bottle of water, or pay for a sandwich. Many are aware that they are fleeing death and are conscious of what has already happened to them.”

Contacted by Mediapart, the Alpes-Maritimes prefecture did not respond to our request for the official record of the number of accidents that have occurred along the French railway lines running into the country from the Italian border.

-------------------------

- The French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Sue Landau and Graham Tearse

(Editing by Graham Tearse)