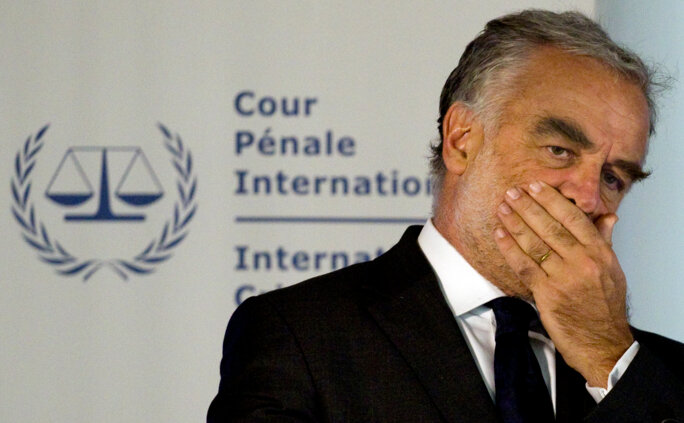

At the same time as he was hunting down the biggest criminals on the planet the chief prosecutor at the International Criminal Court, Luis Moreno Ocampo, owned offshore companies registered in two of the most impenetrable tax havens in the world, documents obtained by Mediapart and analysed by the European Investigative Collaborations (EIC) reveal.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

According to the statutes of the ICC the chief prosecutor, a position Argentine lawyer Moreno Ocampo held from 2003 to 2012, must be a person of “high moral character”. Moreover, it states: “Neither the Prosecutor nor a Deputy Prosecutor shall engage in any activity which is likely to interfere with his or her prosecutorial functions or to affect confidence in his or her independence. They shall not engage in any other occupation of a professional nature.”

This requirement would, on the face of it, seem incompatible with owning an offshore business based in a tax haven.

The reason why a chief prosecutor is required to be so exemplary is that the ICC pursues the worst mass killers in the world. These are men and women of high rank, heads of state, military leaders, spymasters or others who are all suspected of having committed atrocities, whether these are crimes against humanity or genocide. To ensure they are not in a vulnerable situation when faced with those they accuse – who sometimes have the resources of a state or an intelligence service to defend them – the investigators must be above any suspicion. The prosecutor is at the forefront of this group.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

On August 15th, 2012, just two months after Luis Moreno Ocampo left his position as chief prosecutor at the ICC in The Hague, the sum of 50,000 dollars landed in his account at the Abn Amro bank in Holland. The money, which had come via a Swiss account, originated in a company called Tain Bay Corporation registered thousands of miles away in Panama.

In the following months the money continued to flow. At least 120,000 dollars followed the same opaque route: Panama-Switzerland-Holland.

According to the documents obtained by Mediapart as part of the 'The Secrets of the Court' investigation, it appears that the two people hidden behind Tain Bay are the prosecutor Moreno Ocampo himself and his wife Elvira Bulygin. The evidence suggests that after nine years spent at the top of international justice, Moreno Ocampo was working on retrieving part of his fortune which had been put in a safe place.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Tain Bay is not the lawyer's only front company. 'The Secrets of the Court' investigation shows that Moreno Ocampo was also involved with a company in the British Virgin Islands. It was called Yemana Trading and was run from Panama by the law firm Mossack Fonseca. Their name came to prominence in the Panama Papers revelations about the financial structures for the rich and powerful that enabled tax evasion and money laundering on a staggering scale.

Moreno Ocampo's wife Elvira Bulygin was meanwhile the economic beneficiary of a third offshore company, Lucia Enterprises Ltd., based in Belize in Central America. This is another well-known tax haven which has been identified by the European Union as one of the worst in the world. The former chief prosecutor at the ICC was certainly aware of his wife's company: a bank document shows that in September 2012 he transferred 15,000 euros from his personal account to Lucia Enterprises Ltd.

So why did Moreno Ocampo, the best-known figure at the ICC, hide his companies in tax havens around the world? And where did the money come from?

Financial centres such as Panama and the British Virgin islands are among the safest places in the world to stash hidden money and/or avoid paying tax. The authorities of both countries are known for keeping secret the real identity of those who benefit economically from the companies registered there, and also for being very reticent about sharing financial or legal information with other states.

Luis Moreno Ocampo certainly cannot claim he was ignorant of this. Before he was nominated as chief prosecutor at the ICC in 2003 he had built up a strong reputation for his stance on anti-corruption, first of all as a judge in his native Argentina and then as president of the NGO Transparency International in Latin America. In Argentina he had initially made his name as a prosecutor in the 'Trial of the Juntas' in 1985 against the country's former military rulers.

'I don't think it's your business...'

Luis Moreno Ocampo's two offshore companies, Yemana Trading in the British Virgin islands and Tain Bay in Panama, had a bank account in Geneva at the Swiss subsidiary of French bank Crédit Agricole. The former prosecutor went there in person in July 2013 to fetch 40,000 dollars in cash. It should be noted that four years after leaving the ICC, the lawyer enjoys not inconsiderable official assets. According to Mediapart's information he has a property in The Hague worth 1.2 million euros, five properties in Argentina valued at 2.2 million dollars and at least a million dollars in the bank.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Several email exchanges between Moreno Ocampo and Crédit Agricole meanwhile show the care taken by the prosecutor while he was in office to hide his business affairs, which he thought were very profitable, as several documents make clear.

One example: on December 21st, 2009, just a few days before Christmas, the ICC chief prosecutor wrote to his advisor at Crédit Agricole. “I'd like to find a direct way of buying oil in January,” he wrote. But the banker dampened the Argentine's enthusiasm when he pointed out that to trade in crude oil Moreno Ocampo would have to invest at least five million dollars. The banker advised him instead to put his money into investment funds.

On that same day the two men also discussed another, much more embarrassing subject. Under pressure from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) the British Virgin Islands had to change its laws to make it harder to keep the economic beneficiaries of front companies anonymous, with the new law coming into effect from December 31st, 2009. The email exchanges between the Argentine and his banker show that the prosecutor, very aware of the risks of the new legislation, wanted to keep his business affairs away from prying eyes. Time was pressing, too, because the new laws were due to come into force in just a few days.

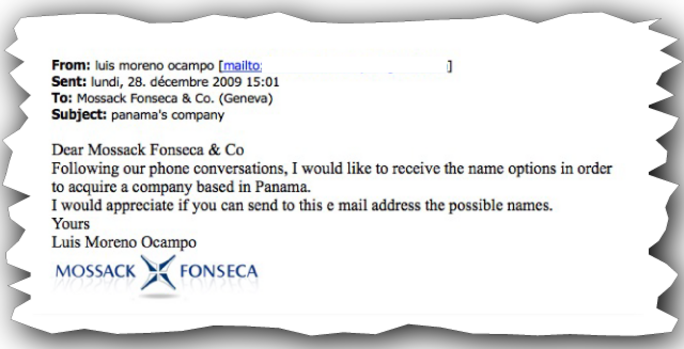

“I've contacted Yemana Trading's manager at Mossack Fonseca,” Moreno Ocampo's banker told him. The advisor also told him that to dissolve the company in the Virgin Islands Moreno Ocampo had to sent the “original certificates” of ownership to Mossack Fonseca. The prosecutor thanked his advisor for his help and took care to carry out all the necessary measures needed to remove the company from the Virgin Islands and remove the risk of exposure. “I've spoken with the people at Mossack Fonseca to open a company in Panama,” Moreno Ocampo wrote to the advisor at Crédit Agricole a few days later. “They told me that they could do it in 48 hours,” he said, clearly relieved.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

The result was that as the new rules came into force at the start of 2010 in the British Virgin Islands, the company Yemana Trading was dissolved.

Moreno Ocampo is, it appears, a man with big financial dreams. When in June 2015 the former prosecutor wrapped up the activities of Tain Bay in Panama, an employee at Crédit Agricole asked if he still wanted to continue using the bank's services. Moreno Ocampo replied that first of all he wanted to make “several millions more”.

When on September 25th the EIC asked Moreno Ocampo, who was on a visit to London, about his various companies, the lawyer initially declared in English: “I don't think it's your business.” He then became embroiled in explanations that were as astonishing as they were confusing. “My salary wasn't enough during my time in office [at the ICC],” he insisted. At the time the chief prosecutor was paid 150,000 euros a year, tax-free.

- Listen below to Luis Moreno Ocampo's initial reaction to the EIC's questions about his offshore activities:

“Offshore companies are not illegal. I paid my taxes in Argentina up to 2003,” he told the EIC. “When I was at the ICC I paid all my taxes there, but I had the right to have money outside. I had to protect myself in a country [editor's note, Argentina] where the banks can decide to take your money. So, yes, I had money outside Argentina. But look at my accounts, there was no income while I was at the ICC. None,” said the former head of Transparency International in Latin America.

The former prosecutor sought to relate his offshore activities exclusively to his past prosperity as an Argentine lawyer. “How I managed my money when I was a lawyer in Argentina is none of your business,” he told the EIC. However, the documents seen as part of the 'The Secrets of the Court' investigation show that while a prosecutor at the ICC he continued to handle his business affairs in the tax havens and was even worried that he name could be exposed.

The lawyer insists he is not a tax dodger or a tax fraud. But he does accept that he did not declare his offshore businesses to the ICC. “They didn't ask me,” he says.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter