The pictured faces of the smiling people in the photo are a little blurry, but the logos that appear above them on the entrance to the building are easily recognisable. It was taken on March 13th 2019, when a group from an organization called the Syria Trust for Development (STD) and French NGO SOS Chrétiens d’Orient (SOS Christians of the Orient) jointly inaugurated a socio-cultural centre in Hamdaniya, a once-wealthy neighbourhood in the city of Aleppo, in north-west Syria.

Throughout the civil war in the country, which began in early 2011, Hamdaniya remained under the control of the Damascus regime of President Bashar al-Assad.

SOS Chrétiens d’Orient (SOSCO) describes itself as an "apolitical" NGO but has well-documented links to the French far-right, like also its founders, Charles de Meyer et Benjamin Blanchard.

Established in October 2013, SOSCO sends volunteers and staff across the Middle East, notably Syria, Iraq, Egypt and Lebanon, and to a lesser degree Jordan, with the stated aim of supporting persecuted Christians. “The association testifies to France’s superior vocation; to reforge the links with the Christians of the Orient,” reads a statement on its website. “A duty which is not simply humanitarian, but also cultural and civilisational.”

In an article on its website about the inauguration of the socio-cultural centre in Hamdaniya, SOSCO presents its partner, the STD, as a "Syrian association". It is, in fact, the largest conglomerate of NGOs in the country, whose founder and head is none other than Asma al-Assad, the wife of Bashar al-Assad.

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo recently called Asma al-Assad "one of Syria’s most notorious war profiteers".

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Created before the revolution to modernise and improve the image of the regime, the STD has established itself since the civil war began as one of the obligatory intermediaries for international organizations wanting to operate in Syria. “The Syria Trust played a major role in the government's plan to defeat the Syrian revolution,” says Ayman al-Dassouky, co-author of a recent report on regime-sponsored NGOs for the European University Institute in Florence, Italy. “It was used to control nascent civil society and attract foreign funds. It has become the main tool for public relations with the West and the international community, capable of redirecting international aid to the regime and its associates.

According to local actors interviewed by al-Dassouky, a researcher specialising in post-2011 Syria, only 20% of the STD's budget – which is largely financed by UN agencies – goes to its supposed beneficiaries, with the majority of the funds co-opted by the Damascus regime of Bashar al-Assad.

The Syrian regime has often helped itself to passing emergency aid convoys, as revealed in numerous investigations and confirmed to this investigation independently by NGOs operating in regime-held areas.

SOSCO told Mediapart that between 2017 and 2019 it had paid the STD 285,752,559 Syrian Pounds (more than 470,000 euros, according to calculations applying exchange rate variations). This is a small donation for the STD, whose budget was no less than 35 million euros in 2018. But it is, Mediapart understands, the largest amount of money SOSCO has ever given to a Syrian organization.

SOSCO’s biggest project was the "construction" of the STD’s Tishreen centre in Aleppo. SOSCO said it contributed 300,000 euros, which also paid for free French lessons.

“We would like to make more [projects] but they are still under study,” former SOSCO Head of Mission in Syria Alexandre Goodarzy told the pro-Assad publication The Syria Times in May 2019.

According to a member of the STD whose name is withheld for security reasons, the Tishreen centre building already existed. It was a slightly rundown public building used for vocational training that the STD did not construct, but simply took over, the source said.

In July 2018, the centre’s Facebook page posted photos of what it described as “the final touches for the opening” but made no mention of any repairs, and showed no destruction. Contacted by email, the SOSCO press office maintained that this "educational and social centre was completely destroyed", adding that the NGO "witnessed” it in this state and was “proud of having rebuilt it".

The STD centre was to provide social services to 3,200 children and 1,600 women, according to a Facebook post from the foundation shared by SOSCO Director General Benjamin Blanchard. According to a local source, these figures were exaggerated as the centre is far from the districts in most need. "Several hundred people benefit from it," SOSCO told Mediapart in an email exchange this month.

SOSCO's donation was modest compared to the 1.3 billion US dollars the STD had for the construction of 15 similar community centres in 2017. But 300,000 euros is a significant sum for the French NGO, which described itself in a special edition of French Catholic magazine L'Homme Nouveau last year as a "humanitarian start-up". In 2016, SOSCO spent just less than 800,000 euros in Syria, according to internal documents obtained by Mediapart.

SOSCO's partnership with the dictatorship’s “first lady” goes beyond Aleppo. Its volunteers have also been sent to an STD centre in Damascus, and the association's website sells soap produced by an STD affiliate. Last year, Fadi Farah, the CEO of soapmaker Ubbaha, became SOSCO’s financial director. Described by the French online publication Intelligence Online as the "key man of the NGO" and the "right-hand man to Benjamin Blanchard", Farah also chaired another subsidiary of the STD, the microfinance company Syrian Handicrafts Ltd., from 2013 to 2017.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

In March 2019, SOSCO's partnership with Asma al-Assad's charitable empire seemed to delight the NGO's director general Benjamin Blanchard, who re-posted pictures of the Tishreen inauguration to his Facebook page with a beaming emoticon (see screenshot right).

But the post disappeared shortly after the US Caesar Act (full title, the Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act) came into effect on June 17th 2020. The legislation not only adds Asma al-Assad to the list of people under sanction, but also makes it possible to prosecute all those who support and trade with regime-linked organizations.

The law is not retroactive. But, in theory, the Office of Foreign Assets Control (the body responsible for enforcing US sanctions) could penalise and fine the French NGO if it continues to fund the STD. Importantly, as Intelligence Online revealed, the Syria Trust deals directly with a bank which has Rami Makhlouf, the under-sanction billionaire cousin of Bashar al-Assad, as a shareholder.

But the cooperation on the ground between the two organizations continues regardless. This August, the French NGO published a video on its Twitter account from a town in the Hama region of west-central Syria, with the caption “the Syria mission continues to donate hygiene packages to #Squelbieh [Suqaylabiyah], in partnership with the Syria Trust for Development”. SOSCO's press office told Mediapart it had no knowledge of STD Sqelbiye, but confirmed that the NGO wishes to continue its cooperation with Asma al-Assad's foundation.

Defending the controversial alliance, SOSCO told Mediapart that, "the STD is also an important partner of the UNHCR, whose aid represents 83% of the STD's budget". While that is true, the United Nations has come under heavy criticism for its cooperation with various bodies directly involved in both state repression and the war effort since revelations on the subject were published by The Guardian in 2016.

That same year, a coalition of humanitarian aid workers and groups from Syrian civil society launched a campaign to persuade the UNHCR to end its partnership with the STD, which they claimed violates all humanitarian principles of impartiality, neutrality and independence.

A report published in June 2019 by NGO Human Rights Watch concluded that “the Syrian government has developed a policy and legal framework that allows it to divert aid and reconstruction resources to fund its atrocities, punish those perceived as opponents, and benefit those loyal to it”.

In practice, it is unlikely that the US administration will go after SOS Chrétiens d'Orient, which trades STD soap bars at 3 euros a piece and has its headquarters in France, an ally of Washington. With the Caesar Act, the US is primarily targeting Russia and Iran, which have helped the Assad regime stay afloat and bypass international sanctions, as well as Arab countries tempted to rekindle economic relations with the regime of Bashir al-Assad.

"But the extensive nature of the American tools means that regardless of the action taken by the American administration, the banks could take preventive measures to avoid any risk of being sanctioned," said Charles Thépaut, visiting fellow at think tank The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. If so, SOSCO could have more to be concerned about from reactions to the new sanctions law in France, rather than the US. In its response to Mediapart, SOSCO expressed concern about the "dangerous repercussions of the Caesar sanctions, which risk penalizing humanitarian action and the Syrian population".

The Syria Trust for Development is not the only pilot fish of the Assad regime that SOSCO has cooperated with. Soon after the NGO’s creation seven years ago, its founders joined forces with Franco-Syrian businesswoman Hala Chawi, an unofficial adviser to the Syrian president.

Their first meeting took place in October 2013, in Damascus. The secretary of the newly formed association, a man called Olivier Demeocq, who previously owned a Paris bar popular with the far-right, went on the NGO's behalf. He was introduced to Hala Chawi by the former representative of the Syrian Ministry of Tourism in France, Frédéric Chatillon, who is a close friend of Marine Le Pen, leader of the French far-right Rassemblement National party – the former Front National – and reportedly close to the Syrian intelligence services. In June this year, Chatillon was convicted of fraud during a trial over the financing of an offshoot “micro-parti” created in support of Le Pen.

Despite being sponsored by the influential Hala Chawi, Demeocq had to travel to Syria three times to organise the first SOSCO visit, which saw around 20 young French people take Christmas gifts to Damascus orphanages. “I said I don't want to be involved in politics," recalls Demeocq. "The Syrian authorities told us: 'Ok, but you will be filmed and watched’."

The Christmas in Syria operation was put together in three months, against the advice of the French foreign affairs ministry, which had cut ties with Bashar al-Assad in 2012. The participants slept in "a hotel reserved by the Syrian government," according to the account given at the time by SOSCO director general Benjamin Blanchard.

"The presidency validated the visas but it was Hala Chawi who paid for everything," said a Syrian humanitarian worker close to the Damascus regime.

The adventure came to a swift end for Olivier Demeocq, who says he now disagrees with the communication strategy of Blanchard and SOSCO President Charles de Meyer, which he considered "communitarian" and pro-Assad. He left the association a few months after its creation.

Funds for an archbishop who defends Bashir al-Assad

For Hala Chawi, however, it was the beginning of a close collaboration. In Damascus, SOSCO set up its headquarters in a house belonging to her family. She was the guarantor and visited regularly.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

After making her fortune as an importer of Baccarat crystal, in 2016 she launched her own charity, Al-Karma ("vine" in Arabic), with the same heart-shaped logo as that of SOSCO, and the two even merged Instagram profiles for a while (see right).

While Hala Chaoui's French connections helped her get an invite to France’s lower house of Parliament, the National Assembly, she remains a shadowy figure in Syria. The Chawi name is best known because her son, George, a member of the so-called Syrian Electronic Army, has been placed under international sanctions.

From a Christian family, Hala Chawi is part of a second-tier bourgeoisie of business people that rose in rank in Syria during the civil war, taking the place of powerful industrialists in exile.

Forging links to far-right would-be humanitarians and also rightwing politicians in France, Assad's advisor appeared to be taking on a new political role of helping to restore relations between France and the Damascus regime.

Contacted by email, Al-Karma told Mediapart "there has been no cooperation between Ms. Chawi or Al-Karma and SOS Chrétiens d'Orient since early 2020”. SOSCO told Mediapart that "to its knowledge, Madame Hala Chawi is not an advisor to President Bashar al-Assad," without denying the existence of its partnership with her.

Before their recent unexplained break-up, the two NGOs jointly organized a concert with the Syrian tourism minister as well as CV workshops in Damascus. But their biggest joint project took the form of a golden propaganda monument, built in front of the Aleppo citadel in April 2017. Next to the Al-Karma and SOSCO logos, the giant slogan reads "Believe in Aleppo". It was erected as corpses still lay under the rubble of Syria's second city, which had been shelled and recaptured by regime forces four months earlier (see this report from news agency Reuters).

The association gave 17,000 euros towards the monument, describing it to Mediapart as "an important project for Aleppines of which we are proud", adding that "the emigration of the inhabitants of Aleppo since the occupation of the city by the Islamic State is a real subject of concern". It was in fact anti-regime rebels who drove the jihadist group out of Aleppo a year before the Syrian Army took over the city. "The return of Aleppines, but also the maintenance of families who have not yet emigrated, requires pride in living in their city," SOSCO told Mediapart.

Hala Chawi did not respond to requests for an interview.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

At a time when the city's water and electricity infrastructure is totally destroyed, the Syrian authorities' “Believe in Aleppo” PR campaign was an attempt to replace images of gutted buildings with those of a secure city, open to displaced people, tourists and investors. Three years on, Aleppo, the most populous Syrian city before the civil war, has lost more than a million inhabitants, most of the industrialists who built up the city's wealth are still in exile and the economy has never recovered. (For more on this subject, see the 2020 report by researcher Joseph Daher).

During the March 2017 inauguration of the monument in the city, SOSCO’s former mission chief in Syria, Alexandre Goodarzy, who once described the Damascus regime’s retaking of Aleppo as a “liberation”, was a guest of honour along with then Syrian tourism minister Beshr Riad Yazji at a ceremony organised by Hala Chawi (as seen in this photo published on Facebook by Al-Karma). Yazji has since been promoted to a post of advisor to Bashar al-Assad.

As its name suggests, the aims of SOS Chrétiens d’Orient is not to maintain the al-Assad regime in power, but to preserve the Christian population in Syria, which it announced after the battle of Maaloula. This small, ancient town, 55 kilometres north-east of Damascus with a sizeable Christian population, was overrun in 2013 by jihadists, who were eventually forced out one year later.

Since 2013, SOSCO has been involved in 400 projects in Syria, according to a special edition about the NGO published by French conservative Catholic magazine L’Homme nouveau in November 2019. Its director general Benjamin Blanchard told the magazine that “each budget is controlled from A to Z to avoid embezzlement or misappropriated uses [of funds]”.

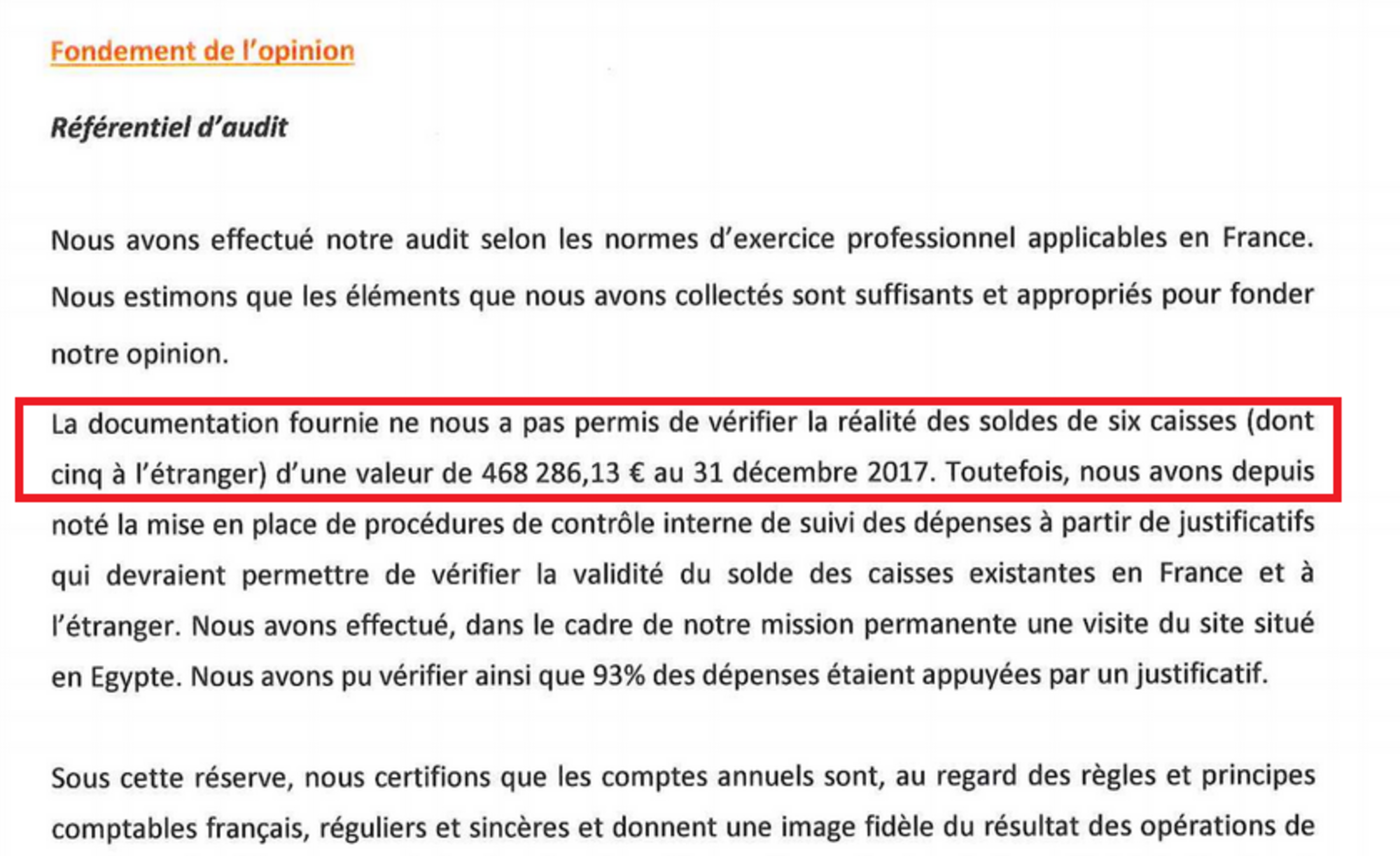

The financial reports of the NGO tell a different story. More than 800,000 euros of its spending were not properly accounted for with justificatory evidence, representing 8% of its budget for foreign missions in 2016, and 9% of that in 2017. However, auditors from accounting firm Actheos certified the spending on the basis of sworn statements.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

In a detailed reply to questions submitted to it for this report, published in the form of a statement on its website, SOSCO said of the 800,000-euro sum that its system accounting was “common for young NGOs” whose “accounting services are in the process of structuring”. It said that aggravating factors included the fact that “French chartered accountants do not understand Arabic and take the precaution of not recognising documents of a handwritten nature, [which are] very frequently used in the Orient”. It added that the sums in question represented “only 4.15% of spending in 2016, and 5.29% in 2017”.

Actheos declined to answer Mediapart’s questions, citing its professional requirement of “confidentiality”.

In 2016, SOSCO announced it had collected 150,000 euros in donations from a halfi-marathon run organised in Paris, which was handed to the “Bâtir pour rester” (Build to Stay) foundation created in 2015 by the Melkite Greek Catholic Church archbishop of Aleppo, Jean-Clément Jeanbart.

In early 2016, Jeanbart, a keen supporter of Bashar al-Assad, visited France to attend an event called "Night of the Witnesses", held under the auspices of Aid to the Church in Need, an international Catholic organisation, in which senior clergy from around the world speak about the local difficulties of their missions. According to a report on the event published by the French far-right online magazine Boulevard Voltaire, and written by Charlotte d’Ornellas, a member of the SOSCO board of governors, Jeanbart told the gathering: “Bashar al-Assad has many faults, but it so happens that he also has qualities. Schools were free, hospitals also. The mosques, like the churches, paid no taxes. But what government in the region does such things, honestly?”

The archbishop promised, following the funds raised by SOSCO in the Paris half-marathon, there was to be the building in Aleppo of a sports complex, the reconstruction of damaged buildings and professional training offered to the local population. According to SOSCO’s annual report of its activities for 2016, seen by Mediapart, it appears that 75,000 euros – half the sum collected – was to be handed to the archbishop’s professional training school.

This month, four years on, one page of the SOSCO website, in English, mentions the training in woodwork skills of nine students. In the statement published on its website this month in reply to Mediapart’s questions, SOSC said: “The professional school ‘Build to Stay’ well and truly exists since 2016, it today teaches 8 [professional] crafts and close to 1,900 young men and young women have emerged from it with diplomas.”

Questioned by Mediapart, Archbishop Jeanbart detailed the school’s activities as being, “training courses of six months in carpentry, plumbing and electricity for the men, sewing, hairdressing and the making of costume jewellery for the women”. He told Mediapart that he could not remember the precise sum that was spent, with what he described as the limited means available, for the reconversion of his archbishopric – “the ground floor and basement of an 11-storey building” – into a “professional training centre”.

In a reply to Mediapart posted on its website, SOSCO said of the planned sports complex: “The sum of 30,000 euros has been frozen while awaiting that the sports field, which was in a combat zone, is once again secured”. For his part, Archbishop Jeanbart told Mediapart that he received “two months ago” 75,000 euros for the sports field on which work had recently begun.

'Their influence is above all their link with the regime'

“Jeanbart is an expert in phantom projects,” commented one former member of the clergy in Aleppo, whose name is withheld. “His foundation has offices in Aleppo, but its functioning is very opaque and the bank accounts of his bishopric are in Lebanon, in his name, without anyone knowing what he does with the money.”

The archbishop firmly denies such accusations. He told Mediapart that the bank accounts in Lebanon are “in the name of the archbishopric” and not his own name, adding that he does not have the right to “speak about or divulge either the contents or the movements” of the accounts.

In Aleppo, Archbishop Jeanbart offered hundreds of families supplies of fuel for heating. But according to a source in the city, while funds for this were collected, those who were supposed to benefit never received the fuel. “It is possible that a few families could have been excluded from the already long list of the deserving,” the archbishop, in reply to the allegation, told Mediapart, “because the sums received could not include all our numerous families, that’s to say one thousand every year.”

In compiling this report, Mediapart has closely studied SOSCO’s prolific public relations communications, which use all the modern tools of the business, and which include appeals for funds for pro-Assad figures like Archbishop Jeanbart, or articles that glorify militia allies of the regime. Among the communications were several projects which appear less accomplished than SOSCO suggests.

After collecting donations (totalling between 200,000-500,000 euros) for the construction of around 100 homes in Aleppo, SOSCO announced on social media that it had completed 24 apartments and that work had begun on 26 others in the Armenian quarter of Al-Midan in the north of the city. In its reply to Mediapart, SOSCO said it has until now built just 14.

Another example concerns Damascus where, in 2018, SOSCO announced it had provided 50,000 euros (representing 70% of the total cost) for the building of an applied architecture studies school for construction professionals. Situated in a building of traditional style in the Christian quarter of the Syrian capital, the school was aimed at “tradespeople, building site foremen and workers to restore the old town of Damascus".

Enlargement : Illustration 8

However, no architect, construction engineer or local inhabitant of the neighbourhood who was contacted by Mediapart was aware of the existence of the project. In its replies posted on its website in response to Mediapart’s questions, SOSCO insisted that “this private professional training institution well and truly exists”, and it included two uncaptioned photos. One of these showed a former deputy-head of its mission in Syria standing beside a plaque that read “Opening of the institute for training in traditional methods of construction under the rule of Bashar al-Assad”, while the other presents a group of 12 people some of whom are holding up illegible documents.

The project for the school was led by an association called Al-Sakhra. It did not respond to Mediapart’s invitation to comment on the project. Over recent months on its Facebook page, Al-Sakhra has promoted sales of its handmade soap, its activities in language teaching and tuition for young schoolchildren.

A Syrian researcher, who asked for their name to be withheld for security reasons, and who is familiar with locations where SOSCO has intervened in missions, told Mediapart: “Their presence on the ground is mostly symbolic, They are praised by certain community leaders who like that they promote their narrative, but they don't have a sustained impact with local communities."

“It's above all their link with the [Damascus] regime that allows them to have an influence and reinforce the sway of this or that group on the ground,” the source added.

Pierre-Alexandre Bouclay, SOSCO’s director of “communications” (press and public relations), when interviewed in the aforementioned feature devoted to SOSCO by French magazine L’Homme nouveau, said that the NGO had succeeded in going beyond the “charity business” as he called it, “where, in front of the cameras, one hurriedly hands out a sack of rice”. Instead, he told the magazine, SOSCO was involved in the “enduring construction” of “large-scale projects”.

In an interview with The Syria Times published in March 2019, SOSCO director general Benjamin Blanchard said that in Syria, where the NGO had sent several hundred volunteers on missions, one of its principal projects was the emergency aid shipment of medicines worth 6 million euros.

By Mediapart’s calculations from available information, spending on communications represents the NGO’s biggest single budget item. Between 2014 and 2018, it spent 9.6 million euros on fundraising mailing and marketing operations in France, while about 16 million euros over this period was allocated to its missions in the five countries where SOSCO then intervened, namely Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, Jordan and Egypt. It appears that communications spending over that period represented 35% of its total budget, whereas most humanitarian NGOs dedicate no more than 20% of their overall budget on communications.

SOSCO dismissed those calculations, and told Mediapart that it was only in 2015, the year when it was launched, that communications amounted to 35% of its spending. “Concerning this figure of 35% for the 2015 budget, it should be placed into context,” the NGO replied on its website. “To launch itself, an association that lives only from private donations must allocate enough means to its communications in order to establish a file of donators who are loyal and guarantee its independence.”

It said that in 2018, “the communications budget represented a little less than 12% of spending”. In reality, after adding the costs of fundraising appeals and marketing operations in France, that proportion rises to 30.56% of the total budget for 2018.

“It is certainly difficult to operate in a country at war, in this instance Syria,” commented SOSCO’s former secretary Olivier Demeocq. He said that since their first visit to Damascus in 2013, the actions of SOSCO’s leaders Benjamin Blanchard and Charles de Meyer “are much more centred on communications than concrete actions. To my eyes, they are above all a communications agency which serves the interests of Charles de Meyer and Benjamin Blanchard.”

Most of SOSCO’s funds come from private donations in Catholic parishes. But others notably include payments from two Members of Parliament (MPs) and a senator, all from the French conservative movement who together donated a total of 16,000 euros to the NGO in 2016. The separate sums came from parliamentary funds known as the “reserve parlementaire”, a now abolished system by which MPs and senators were allocated sums of money to fund associations and other bodies in their local constituencies.

Of the three, the largest donation to SOSCO was made by MP Alain Marsaud,from France’s conservative Les Républicains (LR) party, who signed a cheque for 8,000 euros, followed by Jean-Frédéric Poisson, the former president of the French conservative Christian-Democrat Party, who gave 5,000 euros, and LR senator Joëlle Garriaud-Maylam, who gave 3,000 euros.

Questioned by Mediapart as to whether they were aware of the pro-Bashar al-Assad position of SOSCO, Marsaud said he was not but has “no regret” for his donation. Garriaud-Maylam, who underlined that she gave her donation for one particular project of SOSCO, in Iraq, she said she was not interested in “in rumours about the political adherence or sympathies of the ones or the others”. Poisson declined to reply to the question submitted to him.

In the statement which SOSCO published on its website in response to Mediapart’s questions, which included the issue of SOSCO’s proximity with the Damascus regime as in the partnership with the Syria Development Trust headed by Bashir- al-Assad’s wife Asma al-Assad, the NGO, which said the Trust was a major partner of the UNHCR, began by declaring: “We categorically refuse to have to justify ourselves to some political police which is, furthermore, incompetent.”

“By contrast, we deplore the fact that these journalists devote their energy to harming a charitable organisation whose work is recognised and acclaimed on the ground, instead of, for example, investigating terrorist movements which threaten innocent people.”

While Mediapart apparently exasperates the NGO, similar questions are asked by others. Last April, in a video chat organised on Facebook, Louise Passot, the deputy head of SOSCO’s mission in Syria, was asked “what are the relations with the legitimate Syrian government?”, and which received no reply.

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Frank Andrews and Graham Tearse