On May 17th, the mayor of La Chapelle-sur-Erdre, a small town in the west of France with just over 20,000 residents, pledged to turn the friendship protocol it had established in 2019 with the refugee camp of Jenin, in the occupied West Bank, into a full twinning arrangement. It was, explained mayor Laurent Godet, a way of showing its “unwavering support” for the Palestinian city and its camp, which has been emptied of all its residents and has witnessed a brutal Israeli army operation since January.

A few days later, the city of Strasbourg announced that this June it would vote on a proposal to twin with the Aida refugee camp, near Bethlehem in the West Bank, again “in support of the Palestinian people”, as mayor Jeanne Barseghian stressed. It was a decision that has since made her the target of numerous attacks.

The decentralised or local cooperation between French towns and Palestinian partners, launched in the wake of the Oslo Accords of 1995, initially suffered a “setback after October 7th”, admits Abdallah Anati, executive director of the Ramallah-based Association of Palestinian Local Authorities (APLA). “Some towns in various countries, under pressure from political parties or governments, from lobbies, said they wanted to review their ties with the Palestinians,” he explains.

In the end, no partnership or twinning was halted, as far as he is aware. On the contrary, “relations are now thriving even more than they were before October 7th, because the war has shown what Israel is doing to the Palestinians”, Abdallah Anati says. In contrast, several European towns, including La Rochelle on France's Atlantic coast, have suspended their relations with Israeli partners.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

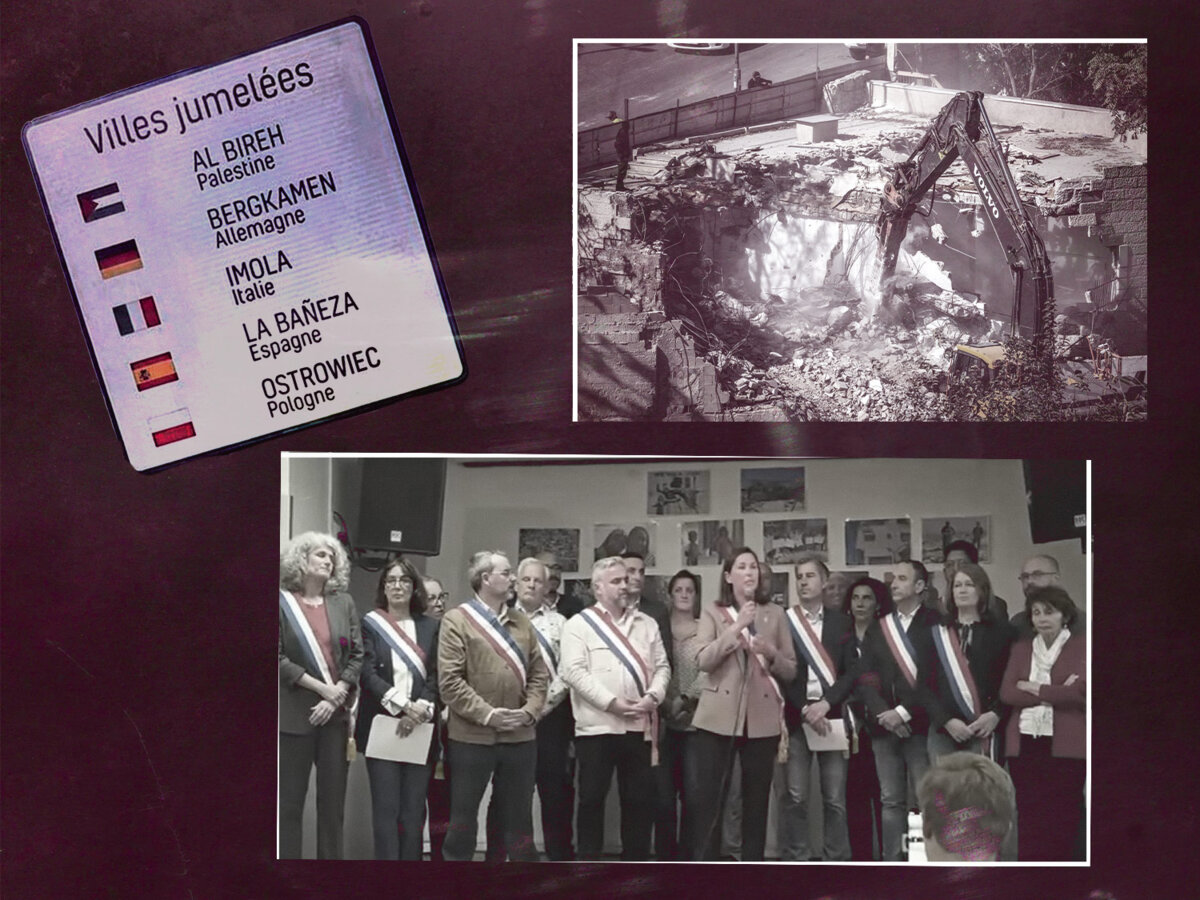

The decentralised cooperation – which bypasses central government - allows local councils to reach out to the world through town-twinning, cultural exchanges, mutual visits and language or sports programmes. “Meetings between peoples,” is how it is described by Patrice Leclerc, the communist mayor of Gennevilliers in the north-west suburbs of Paris, whose town is twinned with Al-Bireh, near Ramallah in the middle of the occupied West Bank.

In the case of Palestine, this cooperation “brings into being a territory which, in the eyes of international law, is not yet recognised” as a state, says Virginie Rouquette, director of Cités unies France (CUF), a cross-party body that brings together French local authorities involved in international action. “As Palestinians we believe that it is the peoples of other countries who will one day bring about change,” says Abdallah Anati. “International bodies have shown they can't make Israel obey rulings, maybe it's the people who can confront the ongoing genocide of Palestinians.”

Obstacles to solidarity

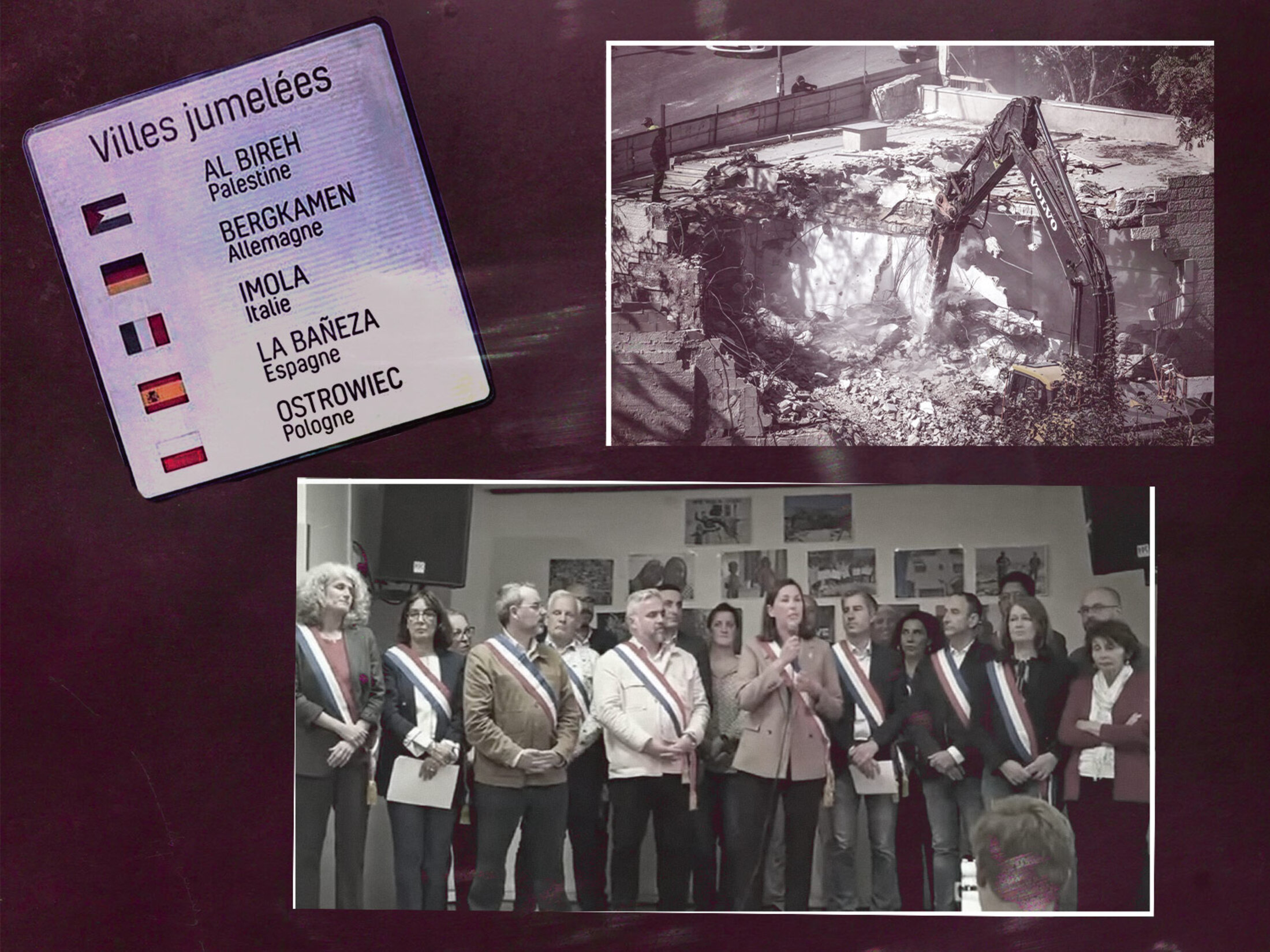

In particular, French councils give financial and technical help to Palestinians. For example, in Silwan, a Palestinian district on the outskirts of Jerusalem’s Old City, local authorities from France are helping to rebuild a cultural centre knocked down by the Israeli city council in November 2024. The site, boxed in and densely populated, is being eroded by Israeli settlers. The centre in question had been one of the few open spaces for locals, 1,550 of whom live in homes under threat of demolition. Between 2019 and 2023, Israeli authorities pulled down 113 buildings in Silwan.

The cooperation also includes exchange trips: 14 French councils hosted 30 Palestinians from Jerusalem in February, and a group of French visitors travelled to the holy city in July 2023. Gennevilliers has set up training programmes on schooling and mental health in the West Bank.

Faced with the brutal Israeli campaign of ethnic cleansing in the West Bank and the genocidal war in Gaza, this locally-based cooperation, which in recent years had become more technical in nature, is once again taking on a political hue, explains Virginie Rouquette. Towns and local councils are often ahead of the curve in taking a stance and urging the state to take action. On the ground, the councillors are of one mind: the French consulate in Jerusalem – which effectively acts as France's diplomatic link with the Palestinian Authority - and the country's other diplomats are working hand in hand.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

By contrast, the response of national politicians has been “shameful, even if it’s starting to change. It needed a bloodbath for them to act,” says Patrice Leclerc, who is also vice-chair of the local council network the Réseau de Coopération Décentralisée pour la Palestine (RCDP). In light of these failures, local councils are stepping up efforts to “make public and highlight the attacks by the settler state”, he adds, pointing to Silwan as an example. “Even if Israel mostly seems to ignore us, now and again they're forced to take notice. It dents their image and that helps produce a bit more solidarity,” he says.

Yet that solidarity was suppressed in France in the months following October 7th, recalls Charlotte Blandiot-Faride, communist mayor of Mitry-Mory in the north-eastern suburbs of Paris. Some state prefects took steps to “remove banners calling for peace and freedom, asked for Palestinian flags to be taken down where they had been raised – all in the name of the state - and sent letters demanding meetings be cancelled, saying it could disturb public order,” says the mayor, who is also the chair of the Franco-Palestine twinning association the Association pour le jumelage entre les camps de réfugiés palestiniens et les villes françaises (AJPF). “We were faced with an institution that was trying to hold back the solidarity movement with Palestine,” notes Charlotte Blandiot-Faride.

Banned from entry

In April, it was the Israeli authorities who brought things to a halt for local elected representatives. In the space of just over a week, Israel first cancelled the visas of five MPs and twenty-two leftwing mayors or councillors set to travel to the West Bank and Israel with the AJPF, and then visas were denied for around 50 other local elected figures and staff due to go on a separate trip run by Cités unies France (CUF) and the RCDP.

On each occasion the Israeli authorities accused the councillors of being backed by groups linked to terrorism. In the first case, the Israeli embassy in France confused the AJPF with the Association France Palestine Solidarité, which it says “backs terrorism”. The AJPF branded the reasons given for its visa ban “slanderous and disgraceful”. In the second, Israel accused the RCDP of ties with the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), a Marxist-Leninist group deemed a terrorist outfit by the European Union.

“We were gobsmacked by the sheer harshness of the Israeli government’s decisions,” says Michaël Delafosse, chair of CUF and socialist mayor of Montpellier, the southern French city twinned both with Bethlehem and the Israeli city of Tiberias, the latter a tie the mayor does not plan to cut.

“There’s a blurring of the lines, where they try to lump together [decentralised] cooperation and terrorism, without proof and in a wholly false way,” says an angry Simoné Giovetti, policy officer at CUF. France's Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the end issued a statement on April 29th calling the Israelis' terror claims “unacceptable” and saying it regretted the visa cancellations, a move it deemed “counterproductive and harmful to Franco-Israeli relations”. The councillors were also invited to the ministry in Paris.

What Israel is banning is international cooperation and, above all, the chance to bear witness.

“It took a fortnight for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to put out a bland, three-line statement,” says Charlotte Blandiot-Faride angrily. “We’ve seen other cases where ambassadors are recalled, where tough talks are had in order to avoid being ridden roughshod over,” she notes.

Patrice Leclerc gives an ironic smile. “We ought to do the same to them!” he says. The mayor of Gennevilliers is himself barred from entering Israel and the occupied territories; he was turned back in 2018 when he and his wife tried to go on a private walking trip in the West Bank. The Israeli authorities accused him of supporting the campaign to boycott Israel, the BDS movement, which “wasn’t true at the time”, he says.

So the fact that Israel is now linking the RCDP to terrorism comes as no surprise to him. “They make these sweeping claims all the time. What they’re really banning is international cooperation and, above all, the chance to bear witness,” says Patrice Leclerc. This is part of a broader Israeli government strategy to “wipe from view and dehumanise the Palestinian people,” agrees Charlotte Blandiot-Faride.

Backing a Palestinian state

Such a climate makes things harder for local councils. “We’ve had to put off events several times due to the security situation, which has led to flights being cancelled, costs shooting up, while bank transfers from councils to Palestinian partners have become more and more tricky, and there are insurance issues too,” says Mélanie Sabot, Middle East officer at CUF.

Councillors now hope President Emmanuel Macron will follow through on his vow to recognise a Palestinian state, something he said this week was a “moral duty”. “It matters because it gives the Palestinians political clout, it backs them in their fight, it could spur on other European countries,” says Patrice Leclerc. “It’s not about sparing Israel’s feelings, it’s about stopping a massacre and a colonisation that will wipe a people off their own land.”

The local council representatives do not see such recognition as handing a blank cheque to the Palestinian Authority, which is hated by its own people. Indeed, in recent years, local councils in France have forged direct links with Palestinian civil society, which is trying to survive in the face of Israeli occupation on the one hand and oppression by its own leaders on the other. “Our support for Palestine is not blind,” says the mayor of Gennevilliers.

International law remains the guiding light for the councils' work, says Simoné Giovetti. Through cooperation with Palestine “we’re trying to keep alive what’s left of the international system,” he says. On May 19th, leftwing leaders in the Seine-Saint-Denis département or county council north-east of central Paris, with the backing of socialist council chair Stéphane Troussel, joined 145 groups, parties and trade unions in calling for Israeli firms to be banned from the Paris Air Show at Le Bourget north of Paris beginning on June 16th, because of the war crimes committed in Gaza. Several NGOs have also filed a law suit over the issue.

Local councillors “are taking clear action, but on the other side we have a president and a foreign minister who just make statements,” says Jacques Bourgoin, former mayor of Gennevilliers and past lead for the Jer’Est project on East Jerusalem at the RCDP. “When we talk to the Palestinians, the last politician they name as truly standing up for their cause is [former president Jacques] Chirac. That should give us all pause for thought here in France.”

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter