First, there are the smells. “A whiff of the cowsheds,” the “intoxicating and deeply familiar, comforting scent of drying straw,” the “wafts” from the pig farms, the “smell of dried leaves, the scent of leaves piled up on the earth”.

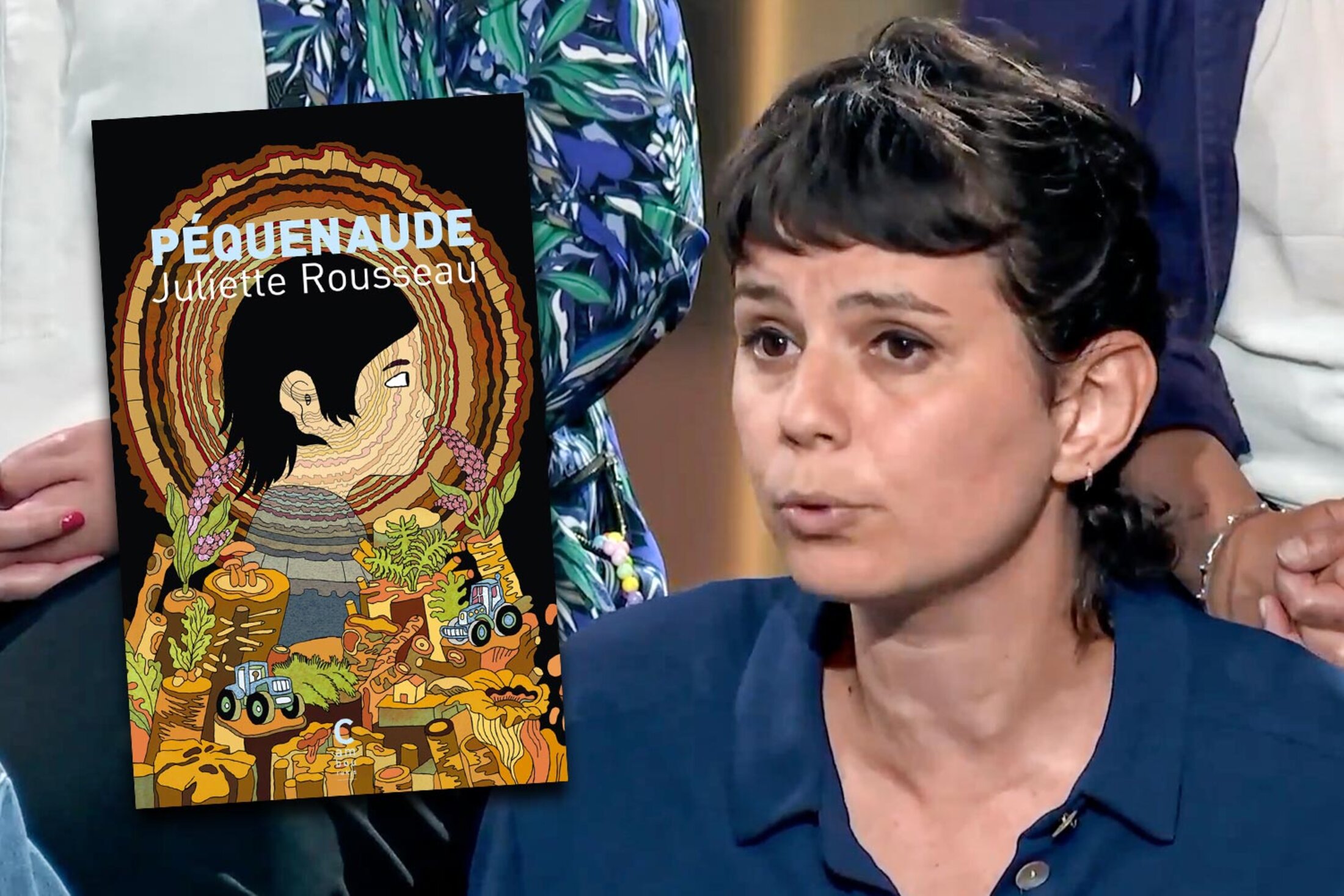

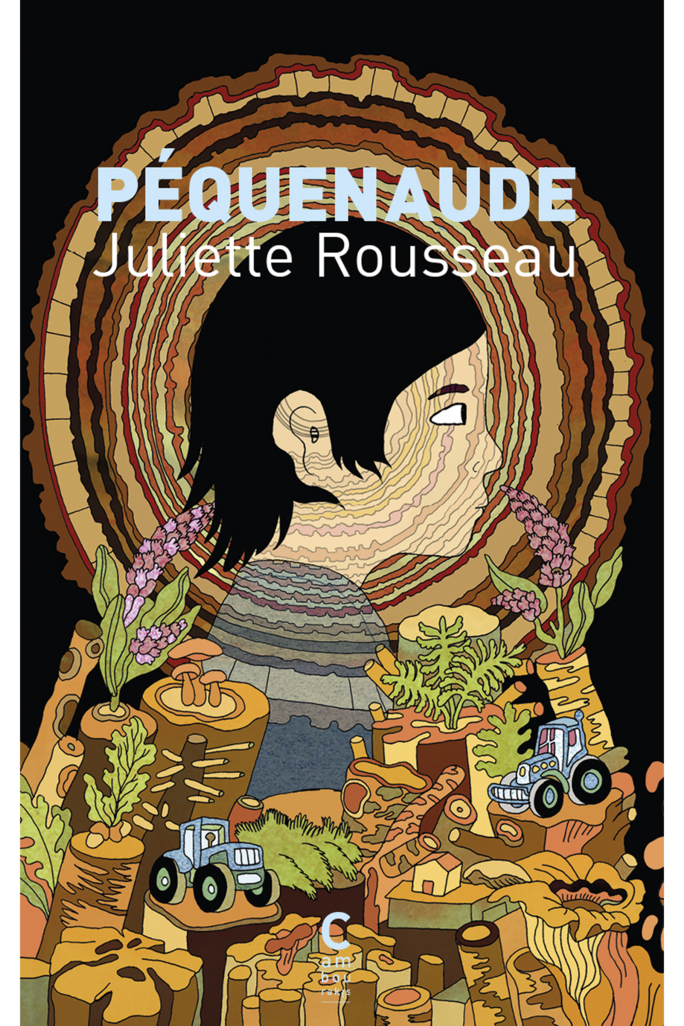

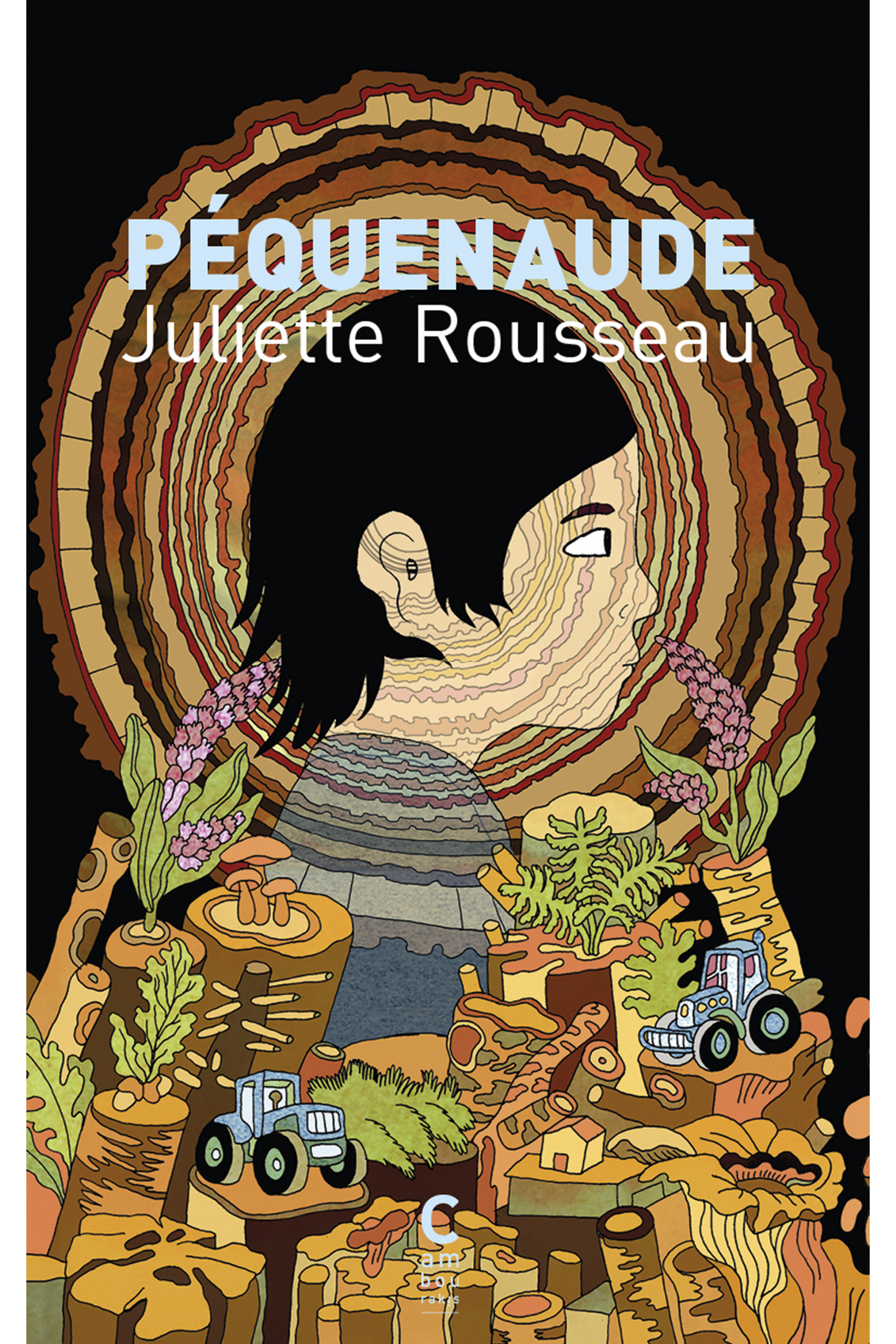

Then there are the tasks. All those things that call the body to action. The logs and the fire in the hearth. The jobs in the garden. The tomatoes and the jam. In 'Péquenaude', (the word means 'country bumpkin' or 'hillbilly') published this autumn by Cambourakis, novelist Juliette Rousseau brings to life the sensory world she inhabits, one far from an urban setting. The novel has an original, poetic narrative, written in prose, rooted in the corner of the countryside in the département or county of Ille-et-Vilaine in Brittany in western France where she grew up, and where she has returned to live after years spent in Paris.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The 37-year-old author, for whom this is her fourth book, explores the concept of rurality. Not from the broad, dominating viewpoint of the city, filled with clichés and condescension (or fantasies, depending on the angle), but from her own necessarily subjective perspective: that of a young woman deeply attached to a land scarred by rampant concrete development and the advances of agribusiness. “Exhausted lands, industrial quantities of filth, and the organised slaughter of animals, out of sight and by the million,” she writes.

Reclaiming a narrative about the countryside

Juliette Rousseau does not try to sugarcoat things, and the provocative 'hillbilly' title drives the point home. This rural world has been stripped of so much: the crushing of peasantry or small-scale farming life, the erasure of regional languages, workers turned into cannon fodder, train lines axed, and public services now in decline. As a teenager, in common with so many others, she dreamt of just one thing: leaving.

Yet at the heart of this collective story lies a deep sense of pride. And with it, the full ambiguity of this relationship with one's rural roots, this “shame-pride duality that defines us when the earth still clings to our skin”.

This resonates with the writing of another author of rural origins from a generation earlier, the novelist Marie-Hélène Lafon. “I was more inclined to pride than shame, but I am well aware that they are deeply linked, that one can compensate for the other, and that one can be a way to avoid seeing the other because it’s too painful, because it’s unbearable,” said this author from the Cantal in central southern France in a documentary series on France Culture public radio, on which she and Juliette Rousseau were both guests.

What emerges from between the lines of 'Péquenaude' is a desire to reclaim a narrative about the countryside, to prevent that story from being monopolised by the far-right, and to dispel the image of these simply being conservative lands. In reality, the rural world is marked by great diversity, social inequalities, struggles, and relationships based on power. Juliette Rousseau’s approach – she has long been active in the domain of alter-globalisation and the climate movement - is political. She wants to reconnect with what we have lost. “And it’s not just the landscape itself that has changed, it’s that we have collectively lost our connection to it, our ability to shape it, maintain it, to subsist from it and be content with it.”

It’s the sudden appearance of a species that we thought had disappeared, the relentless return of leaves on the oaks, the regular visits of hares and foxes to the village.

The poetic author knows her writing will not be universally acclaimed. The countryside is “seen as a profoundly backward, conservative space, and taking an interest in it, claiming it in another way, is immediately viewed with suspicion”. Her work is full of doubts and questions. Is this the right place for her? To sit at a table and write, when one comes from such a hand-to-mouth peasant world? To describe a world so close to oneself without the protective anonymity of big cities? “The 'country bumpkin' in me won’t forgive the writer for her frivolity,” she writes.

Autumn, winter, spring, summer. The four seasons pass as the pages turn, nature’s spectacle unfolds, and so does climate disruption. The “roses that never stop blooming”, the winters that “gradually disappear in favour of endless autumns”, things barely noticeable in the city but magnified in the countryside.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

In this world of simple, modest joys crafted by the poet and tinged with melancholy, a quiet sense of peace timidly breaks through. “It’s the sudden appearance of a species we thought had disappeared, the relentless return of leaves on the oaks, the regular visits of hares and foxes to the village. The softness of some mornings. A day crackling with light in the midst of winter.” It is about holding onto this thread, telling ourselves that everything is not lost, that we still have the means to protect all this life that bursts forth each spring.

With a style that weaves together personal observations, lived experiences and family history, Juliette Rousseau joins the ranks of writers who have emerged from the rural world in recent years. One thinks of the poet Hortense Raynal (her collection 'Ruralités' is published by Les Carnets du Dessert de Lune), who roots her poetry in the memory of peasant houses and contemplation of the landscapes of the Aveyron in central southern France: “Landscapes that are strange, malevolent and loved landscapes all at the same time, vanishing despite the photographs that attempt to pin them onto the cruelly charming map of existence”. Then there is sociologist Valérie Jousseaume, who also plays on the notion of ambivalence ('Plouc Pride. Un nouveau récit des campagnes' – 'Hillbilly Pride. A new narrative for the countryside', published by L'Aube).

Such writings refuse to accept the disappearance of this world, and seek to restore it. To borrow Juliette Rousseau's own words, this world is still present “in the language and what remains of vernacular names, in the plump and stubborn accent”. Now it is about preserving it.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter