It's a vaudeville act that is constantly replayed within the wider spectacle of the French economy. At regular intervals a cupboard opens and a horrified finance minister discovers the existence of debt obligations that he himself put in there. There then ensues a familiar scene of general panic in which doors are slammed amid talk of bankruptcy, calls for restraint and mutterings about a potential attack from the financial markets.

Everyone then demands a reduction in public spending and the imposition of austerity to “save the country”. Meanwhile, a member of staff in the minister's office pulls out a stack of very serious economic studies showing that austerity in fact strengthens “structural growth”. So, in the face of populism, reason thus apparently dictates a cut in public spending.

The scene continues with a round of severe austerity which mainly affects the poorest in society. Poverty grows, the country sees structural growth collapse and recession is guaranteed. The denouement comes with the same minister swearing, hand on heart, that he will not be taken in again. Before returning to fill up the cupboard...

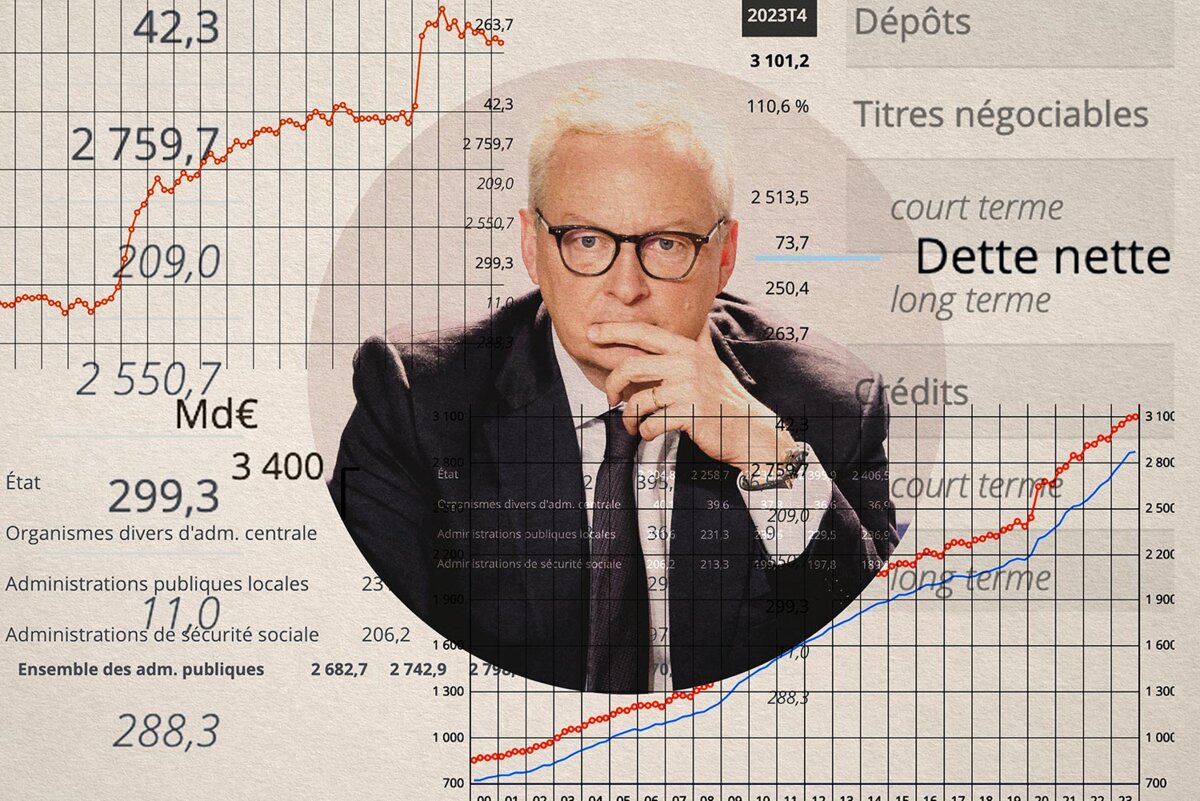

Enlargement : Illustration 1

In the first months of 2024 France seems to have plunged straight into this bad vaudeville act, one that has been replayed a hundred times over but whose concrete consequences are nonetheless considerable. Alarmist speeches about the level of public debt are growing in number. As Benjamin Lemoine, a sociologist and author of the book “L’Ordre de la dette” ('The Order of Debt', published by La Découverte in 2022) told Mediapart “the element of surprise from the political-media world is faked”.

He recalls that “when interest rates were at their lowest, thanks to the ability of the ECB [editor's note, the European Central Bank] to manage the state bond market, the concern for the public authorities was the disappearance of public debt as a problem”. Once this central bank support was lifted “public opinion had to be prepared for what we see today which resembles a return to the order of debt”. France's economy and finance minister Bruno Le Maire has been doing the groundwork on this for more than three months.

Indeed, the minister has himself opened the cupboard. Suddenly France's public debt, which he has merrily helped increase through handouts for the private sector, has become unsustainable. Suddenly, there is an emergency.

In his book-length personal manifesto called 'La Voie française' ('The French Way') published last week by Flammarion, the minister devotes a chapter to the need to drive down debt. And he makes a very clumsy attempt to set out the reasons for the urgent necessity to reduce spending. It is a real Aladdin's cave of arguments about the problems associated with high spending, ranging from the raising of taxes (which is due to end in June) to the “downgrading of France” (using complete anachronisms that invoke the spending of kings Louis IX and Louis XIV) and that ultimate proof: reduced growth.

Since it became apparent that the government's growth forecasts for 2024 were far too high, the ruling majority has constantly deployed this last argument, which is summed up in the writing-obsessed minister's book in this way: “Weak growth slows down our debt reduction: we then have to find other measures in the short-term to reduce debt.”

The vaudeville act is thus in danger of turning into a pastiche of the satirical farce Ubu Roi, because cutting spending to reduce debt at a time of weak growth is guaranteed to weaken growth even more - making it even harder to pay off the debt. This was clearly shown in recent years by the eurozone crisis.

Bruno Le Maire and today's leaders were themselves around at that time. They should have remembered this simple lesson. But they now have a different story they want to tell us, exactly the same one as in 2010-2014 when belief in the “expansive austerity” proclaimed by the ECB president Jean-Claude Trichet went on to plunge the eurozone into the longest recession in its history.

The panicked reduction in debt back then contributed to increasing the impact of the debt over the long term. And did the rush to reduce public debt in the eurozone boost our ability to invest in the future and build a stronger and more lasting economy, as was stated? No, indeed the reverse happened.

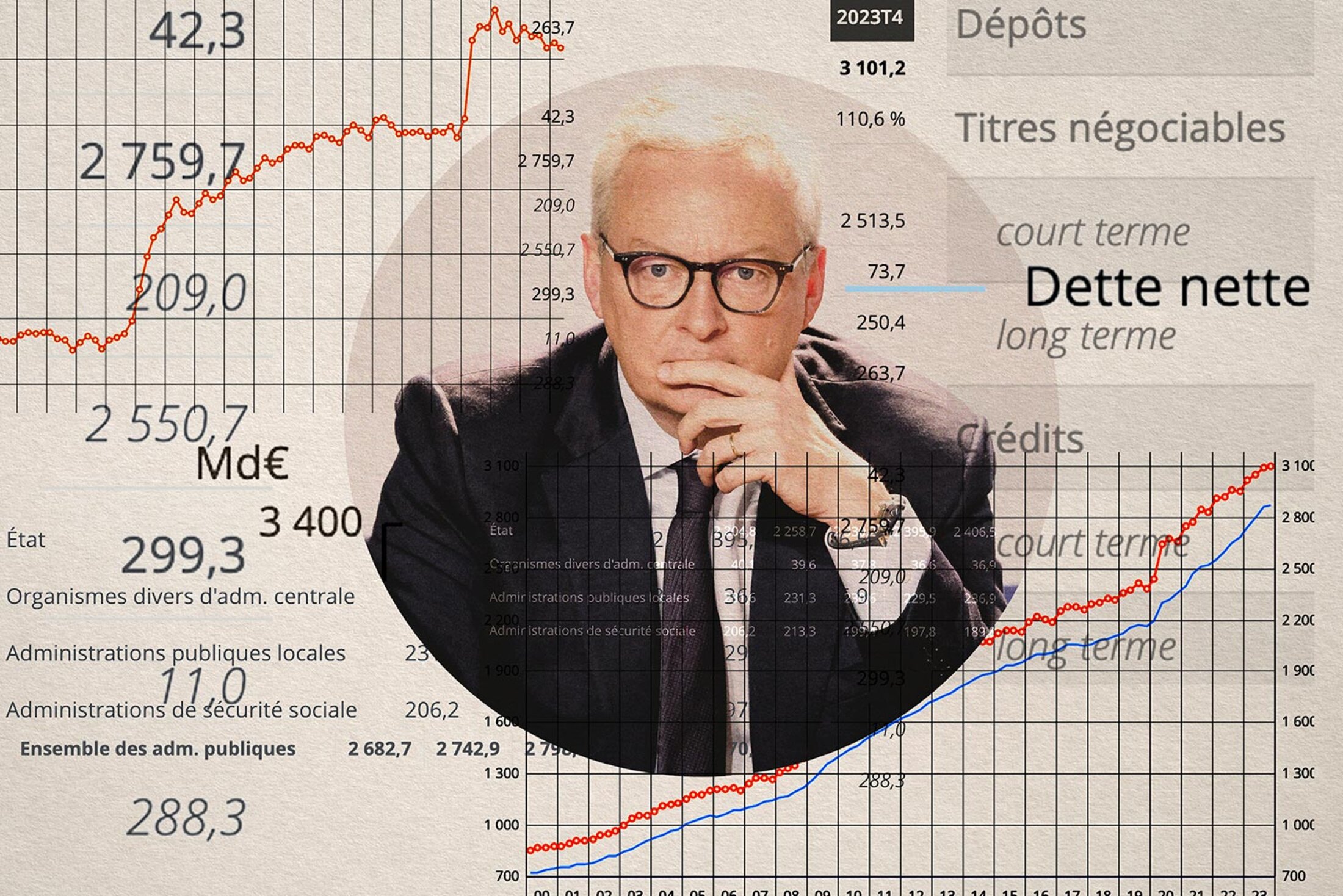

Cour des Comptes pulling strings of the debt tragedy

Yet it is this same narrative that one has seen being deployed in public debate over the last three months. And nor should one underestimate the role of the public audit office, the Cour des Comptes, in helping construct this story.

For some years this public institution has been evolving into a guardian of the temple of financial orthodoxy. Because of its theoretical independence it is a very useful reference point when it comes to constructing the panicky narrative over debt. In this it plays a very well-established part in justifying the idea that debt has become unsustainable.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Like his predecessor Didier Migaud, the institution's lead president Pierre Moscovici - who was himself a disastrous steward of public finances when he was finance minister from 2012 to 2014, overseeing a policy of “expansive austerity” which took public debt from 80% to 95% of GDP – is himself employing the classic language of fear and shame to justify a policy of rapid debt reduction.

He has been drawing parallels, an eternal ploy of neo-liberal politicians. In an interview with La Dépêche newspaper on March 13th, the lead president of the Cour des Comptes attacked “our public spending” which had “deteriorated the most” in the eurozone economies. Then he picked up on the familiar refrain of a ruined future. On March 12th, during the presentation of the Cour's report on adapting to climate disorder, he claimed that the “preoccupying” situation in our public finances made it more difficult to find the resources to deal with the environmental crisis.

In short, everything – even the unjustifiable – is acceptable in order to justify austerity. For it is hard to see how one can find 20% of GDP to deal with the impact of Covid – at a time when total public debt was at 100% of GDP – but not be able to find the money needed to adapt to the climate when debt is at 110% of GDP.

Fear and trembling

Once this narrative framework had been established, the media joined in the fray, increasing the number of articles on the issue of debt and insisting, with the help of polls (such as one in La Tribune Dimanche more than ten days ago), that “France is afraid” of the level of debt. The headlines and texts have becoming ever more alarmist, including talk of the need for a “detox cure for our debt-drugged state” in Le Point news magazine and claims by economics commentator François Lenglet on TF1 television that “France is on the edge of the abyss”.

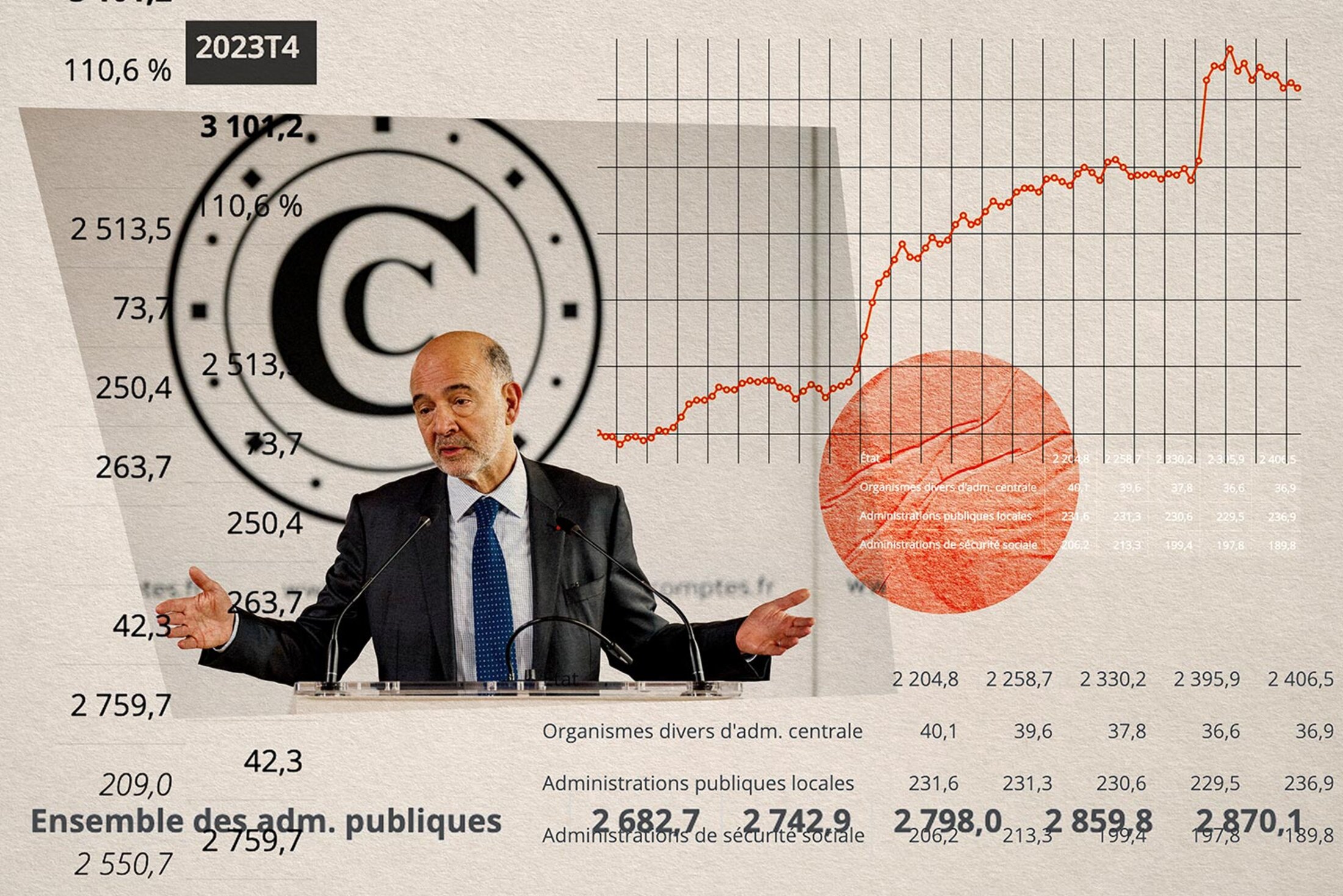

The announcement on March 26th that the public deficit - the difference between revenue and spending - was 5.5% of GDP in 2023 against 4.8% the previous year was thus treated as if it were a major shock. One phrase soon started to do the rounds of television and online news sites: “out of control”. On BFMTV the question was asked: “What's the government going to do?” This is despite the fact that public debt – the overall accumulated debt from past deficits – actually fell by two percentage points against GDP last year, and despite the fact that there has been no concern in the markets.

But nonetheless, action is deemed to be needed - and fast. Inevitably Bruno Le Maire – speaking on RTL radio – and Pierre Moscovici on France Inter radio stepped in to reinforce this idea of an emergency, using the arguments cited above and adding another: that of morality. For if France's national debt is getting “out of control” then it's because the French people are too blasé and unable to display the necessary rigour.

“Our national culture is such that after crises we don't know how to reduce our dependence on spending quickly enough,” Pierre Moscovici told La Dépêche. He said the French public also refused to see the “truth” in front of their faces, and the lead president at the Cour des Comptes called for a “frank debate”. To cap it all, finance minister Bruno Le Maire insisted that in relation to the state reimbursement of patients' medical costs there could “no longer be an open bar”.

Behind these moral lessons there is of course an objective; that of preparing public opinion for the “difficult but necessary” austerity which will hit those seen as “profiteering” from public spending. As far as Benjamin Lemoine is concerned “everything is seen in the context of public spending and we automatically forget what produced the deficit: the anti-tax message and the way the state helps capital”. A study by the economic research body the Institut de Recherches Économiques et Sociales (IRES) puts the cost of various forms of aid to the private sector at close to 200 billion euros a year.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

To divert attention away from this, the focus is shifted instead to the issue of social expenditure and public services. They are held responsible for the growing debt levels and the debt narrative helps justify future cuts in both public services and social spending. These have already begun with an emergency reduction of 10 billion euros in the budget in February and numerous reforms made to the unemployment benefit system. But more is still to come.

The final scene: social strife

Above all, this political narrative about debt, which is hammered home continually by the government, part of the opposition (including now even the far-right Rassemblement National) and 'experts', helps justify the pursuit of class politics. It can be summed up in this way: the spectre of debt is used to dismantle what remains of the welfare state, in order to maintain the transfer of resources towards the private sector and prop up its profitability in the face of stagnating growth.

The sight of this weeping and wailing over public debt thus appears to resolve an internal conflict within capitalism caused by recent economic developments, at the expense of those in the workplace and public services. Benjamin Lemoine highlights the renewed pressure coming from creditors and the financial sector in recent times. “As the performance of risk-free assets are no longer explicitly guaranteed through purchases by the ECB, it falls to governments to reassure lenders,” he says. “While the debt extortionists' revolver had been deactivated by these [ECB] purchases, it has [now] been partially rearmed.” He points out that unfettered refinancing on the debt market is “produced politically via promises of reforms to investors”.

But this logic has run slap bang into structurally weaker growth and the permanent need of other sectors, in particular industry, to benefit from direct and indirect flows of public money. To resolve this tension, and satisfy all sections of capitalism, the solution is thus to make sure that the debt impacts on social expenditure and public services. Bruno Le Maire's proposal to increase VAT or sales tax to solve the problem – something already implemented during François Hollande's presidency (2012 to 2017) – also fits into this framework of social repression.

“The return of the debt order has consolidated class inequalities,” says Benjamin Lemoine. He says that there is a “social specification for maintaining debt as a risk-free asset for financiers” and that the “most vulnerable, those who depend on public services, as well as the spending sections of the state (health, education, research etc)” are “automatically” the fall guys in this “perpetually repeating” sequence of events.

In an article in the New Left Review in 2020 the American economic historian Robert Brenner summed up the “new regime of accumulation” he calls “political capitalism” in this way: “The politically driven upward redistribution of wealth to sustain central elements of a partially transformed dominant capitalist class...” It is this logic that seems in full swing in France's case.

“The maintenance of debt order demands a constant mixture of support for private capital and an ability to ensure servicing of the debt without political shocks, and for years this ability has rested entirely on sacrificing the welfare state,” says Benjamin Lemoine. The problem is that this reasoning, backed as it is by the debt narrative, is breaking down in every respect. Not only is this approach not producing growth, it is also, because of the social and environmental cost, undermining the ability to repay the debt. Social strife fuelled by the debt narrative is a dead-end. Behind the vaudeville act there is, indeed, a deadly tale.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter