The body of 24-year-old Steve Maia Caniço was finally found on Monday, floating in the River Loire in the north-west town of Nantes, just several hundred metres from where he apparently fell from a quayside during an overnight rave party on June 21st.

The event, one of thousands of street parties held around France during the traditional summer solstice Fête de la Musique, was held on the ‘Wilson Quay’ lining the tip of an island, the île de Nantes, that divides the river in the centre of the town. On the night of June 21st, around a dozen sound system speakers pumping out techno music had been set up, as authorised, along the quay where an estimated total of two thousand people had gathered.

At around 4am, the police turned up to ensure the DJs switched off their loudspeakers at the pre-ordered time limit set by the local authorities. But one of the partying groups, made up of several hundred people and situated beside a hangar at the end of the quay, was reluctant to do so. After finally agreeing to stop the music, they soon put it back on, and the police returned to disperse them.

Their heavy-handed intervention, in which helmeted and shield-carrying officers used batons, tear gas and stun grenades, LBD rubber pellet guns and Tasers amid chaotic scenes that have been posted on social media, is now the subject of major controversy, a second official inquiry, and conflicting accounts. The officers claim their use of force was necessary after they were pelted with projectiles, but it has since emerged that during a similar confrontation there during the Fête de la Musique in 2017 the police made a tactical withdrawal because of the dangers at the site. Notably, the tall quayside has no railings, and during the police charge last month at least 14 people tumbled into the river, but survived.

Steve Maia Caniço was last seen alive close to the sound system, and in all probability he fell into the river while fleeing the police attack. Caniço, who worked as an assistant for after-class extracurricular activities at a school near Nantes, could not swim and his mobile phone, which friends had frantically called in vain after his disappearance, last connected with the network at the spot where the party was held.

In the days and weeks following his disappearance, amid growing anger at the police’s behaviour that night, protests and tributes to Caniço were held in the town, the movement rallying behind the slogan “Where is Steve?”, which appeared on banners draped over statues, on posters and on elaborate graffiti by street artists depicting the bespectacled young man, who was described by friends as a quiet and non-violent character. The socialist mayor of Nantes, Johanna Rolland, and several members of parliament demanded, in both the lower house and the Senate, that the authorities carry out a proper investigation into the police conduct on the night of June 21st.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

His body, found on July 29th by a passing boat, had spent 38 days in the water despite earlier searches by frogmen, and was finally identified on July 30th. In a declaration later the same day, Prime Minister Édouard Philippe announced that a report by the French police’s internal investigation branch, the IGPN, had found nothing to directly link Caniço’s disappearance with the police charge that night. It was the first mention of the result of the IGPN investigation, which had been concluded earlier in the month. Philippe also announced the launching of a new investigation, by the public administration’s general inspectorate, which is due to report back later in August.

The discovery of Steve Caniço’s body and the conclusions of the IGPN have fuelled increased outrage over policing methods in France, following the tragic incidents during demonstrations by the rolling ‘yellow vest’ social protest movement. These include the death of an 80-year-old woman in Marseilles, when a tear gas grenade inexplicably fired at her apartment window exploded in her face, and hundreds of recorded cases of serious injuries, including people who lost use of eyes and limbs, caused by rubber pellets and stun grenades fired by police.

On Wednesday, Mediapart met with two of Steve Caniço’s friends (whose last names are withheld here) beside the small hanger on the quayside where he was last seen. “This time, the authorities have transformed anger into hate,” said Pierre. “It’s horrible,” said Alexandre. “In fact, they have no realisation,” he added, referring to the extent of the violence witnessed on the night of June 21st. Their friend’s body was found just a little further down the river from where they were standing, behind the old hangars of the Nantes port, where trendy bars are packed with customers. “So close to here,” said Pierre. “What were the divers doing during the month?”

The deep resentment that until now has focused on the police is now felt towards the government, seen as covering up their actions. “For one thing, when you are concerned about something, you don’t mispronounce the name of the person like the prime minister did in front of the cameras,” added Pierre, sitting in a sofa that had been left at the scene, who described the conclusions of the IGPN as “taking the piss”.

For Alexandre, “These politicians are irresponsible, this case does absolutely not trouble them. They are trying to clear themselves, to drag things out and forget things with new inquiries. It’s clear that at heart, what counts above all for them is is their image, which they don’t want to stain.”

Since the discovery of Steve Caniço’s body and its formal identification on Tuesday, many others who knew him have not wanted to return to the quay, which over the previous month had become a rallying point and place of commemoration, fleeing the media attention now centred at the spot. “Too many media have come along, said Pierre, “some of them springing on us.” Close to him were bouquets of flowers, some wilting, that had been left in tribute to the young man. On the walls of the hangar are various inscriptions, one of which read, “We’ll know each other again in a world that is free”.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

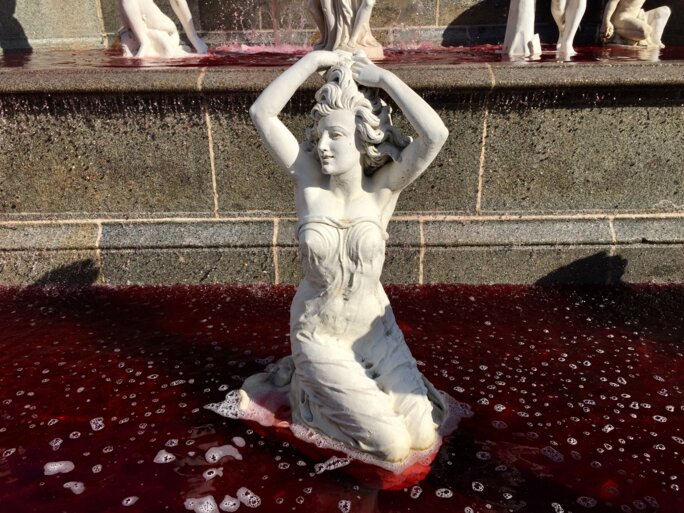

A few kilometres from there, in the town centre, the water of the fountain standing on the Place Royale has been coloured red, attracting the attention of summer tourists. On Tuesday, a banner which had been placed there asking “Where is Steve?” had been partially painted over in black to read, simply, “Steve”. It covers a bronze statue of a sitting woman, a representation of the Loire river, transformed into a symbol by a collective group behind this homage to Steve Caniço. “We wanted to mark people’s minds without causing hurt,” explained Quentin, a soft-spoken artist. “It’s a difficult balance to which we gave a lot of thought, but something had to be done. With the black, we are marking a mourning. Now there is a homicide, there are people responsible.”

The collective of around ten artists and locals, none of whom were acquainted with Steve Caniço, talk of “a new struggle” to come, for Caniço but also, in the words of Stéphane, one of the artists, “for all the other victims of the police”. They have already posted up flyers around the town with the names of people who have died over recent years in confrontations with police. “Here, it’s the police who decide if things go well or turn out bad,” added Stéphane. “Values are turned upside down, victims are transformed into perpetrators.”

He referred to various incidents of alleged police violence, which include a secondary school student who lost use of an eye after being hit by a rubber pellet during a demonstration against educational reforms in 2007, the cases of three people similarly injured to the eye – one of whom lost their sight – in demonstrations in 2014 against the building of an airport on nearby countryside (a project that was finally abandoned) and the fatal shooting of a 22-year-old man who tried to escape a police road block. Stéphane said a demonstration against “all thise police violence” was planned for next Saturday.

“It’s not over, these reactions by a government that doesn’t excuse itself are indecent,” commented Kim, one of the DJs present at the techno parties on the Wilson quay on June 21st. “I’ve nothing against the police as such, but not regarding that which is terrorising France. Steve must become a symbol so that this never happens again. It must really remain engraved in stone so that people are conscious of what was done to him and his family.”

Kim’s friend Claire was also present on the quay that night. She recalled the teargas that “blinded” her, the stun grenades that were fired and the rubber pellets. She said Prime Minister Édouard Philippe’s statement on Tuesday in which he cited the IGPN as claiming there had been “no charge” by the police was “inadmissible”. She said she had been affected by the first salvo of tear gas grenades launched “without warning in the direction of the Loire” when the group began playing music again after the police had first told them to disband. “Nobody voluntarily threw themselves into the Loire,” she said.

Samuel Raymond runs an association called Freeform which promotes parallel "free parties". He called the IGPN report “incomplete” and answered none of the questions asked. He welcomed the new inquiry now underway by the public administration’s general inspectorate “which might produce more serious elements”.

Announcing the launch of that inquiry on Tuesday, the prime minister said it was “in order to go further and to understand the conditions of the organisation of the event by the public authorities, the Town Hall and prefecture, and also by the private organisers”. Recognising that she was targeted by that statement, Nantes mayor Johanna Rolland took to Twitter with the response: “I observe that after five weeks of investigation, the IGPN is still unable to say what happened during the night of last June 21st-22nd on the Wilson Quay in Nates. That is at the very least troubling and disturbing.”

Goulven Boudic, a political science lecturer with the University of Nantes, believes Rolland made the mistake of not taking a clear stand immediately after the controversial police intervention. “Whether she is legally responsible or not is of little importance,” he said. “But the whole debate will move to the this new issue, evacuating the initial question, this question that should have been hammered out from the beginning; why was there this [police] intervention? Why was there this violence?”

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version, with added reporting, by Graham Tearse