The war veterans portfolio is not the most coveted job in any French government. Spending one's days commemorating the past and the dead is certainly not the dream of most politicians. It was Geneviève Darrieussecq who took on this thankless junior ministerial role under President Emmanuel Macron in 2017. But she cannot have anticipated that the position would also involve commemorating the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-1871 which ended 150 years ago this January.

This was, after all, a conflict which witnessed a string of French military defeats. And in the space of a few months the country saw its governance switch from that of an empire under Napoleon III to a Republic proclaimed - in the best tradition of Parisian uprisings - from a balcony at city hall in Paris, to the Third Republic. This new regime then bloodily suppressed the Paris Commune insurrection in May 1871. In short, the junior minister's job meant that she had to commemorate utter failure by both the French armed forces and those who commanded them.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

However, we have to acknowledge two smart moves by Geneviève Darrieussecq's advisors.

The first of these was to have chosen – and we should praise their knowledge of history – three 'glorious defeats' for the junior minister to commemorate. These were three battles where the French army appeared to save face. It is fair to say that it would have been very hard to have commemorated the army's utter routs. Such as, for example, the Battle of Sedan which ended on September 2nd 1870 with France's emperor Napoleon III surrendering to his “brother” - the term used in the surrender - Wilhelm I, King of Prussia. Or the Siege of Metz that ended a few weeks later, when the 170,000-strong French army commanded by Marshal François Bazaine that had been trapped inside the city capitulated without a fight, leaving artillery and other military equipment in the hands of the Prussian forces. This was an event without parallel in contemporary military history. In 1940 the French Resistance remembered this act by denouncing not just Marshal Philippe Pétain - Vichy France's head of state - in their leaflets but Bazaine too.

The second shrewd move by Geneviève Darrieussecq's advisors was to have found a contemporary patriotic message for all the commemorative ceremonies that have taken place since August 2020.

So before an audience containing German officials at Gravelotte in the Moselle département or county in north-east France, the minister praised Franco-German reconciliation at a site where on August 16th 1870 thousands of French and German soldiers died with neither side really winning the battle.

At Bazeilles in the Ardennes, where French marines ambushed Bavarian soldiers in September 1870, Geneviève Darrieussecq paid homage to the “Marsouins” and “Bigors” - contemporary nicknames for the marines – and “sappers”. Using the occasion as a pretext for lauding French troops currently involved in overseas operations, the minister praised the marines of Bazeilles who “remain the symbol of a France that doesn't give up, which doesn't surrender its arms without a fight: which when it yields only does so honouring its flag”.

Finally, on December 2nd at Loigny-la-Bataille in the Eure-et-Loir département south-west of Paris, the minister referred to the “lesson of Loigny” and said that France had put “political opinions” and “daily disagreements” behind it to rally together. This view was based on the fact that troops from the old Catholic Papal Zouaves regiment had taken part in the battle at Loigny, fighting under their Miles Christi or Soldier of Christ banner.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The most astonishing thing about this marathon of commemorations by the junior minister is that it was not her office that was behind them. “The 1870 commemorations have always been the exact opposite of those for the First World War,” notes historian Benoît Vaillot. “[They are a ] private and not a public initiative, and are organised around local and not national memories.”

This hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the Franco-Prussian war has been no exception. The commemorations would not have taken place without the efforts of Souvenir Français, an association that maintains the graves of France's war dead and which was created 16 years after the end of the Franco-Prussian war. Its dynamic president, Serge Barcellini, worked hard to persuade the state to commemorate the war based on a simple idea: that the 150 years could be divided into two halves.

The first half comprises 75 years of Franco-German conflict (1870 – 1945) and the second half consists of 75 years of friendship. The slogan struck a chord, and Geneviève Darrieussecq, who perhaps needed a change after four uninterrupted years of marking World War I and then a triple anniversary of Charles de Gaulle (the 130th anniversary of his birth, the 80th anniversary of his famous appeal from London for the French to resist Nazi Occupation, and the 50th anniversary of his death), was persuaded.

Meanwhile, Souvenir Français proceeded with its own programme of memorials and also managed to get the 1870 war put on school curriculums, for which it helped supply teaching materials. Another initiative, carried out in partnership with the Fédération Française de Généalogie, has been to encourage towns and villages to engrave the names of those who died in the battles of 1870-1871 on their local war memorials.

This is an issue which highlights the extent to which this war has been forgotten. Every French village has a war memorial. But it is very rare for them to feature the names of soldiers who died in the Franco-Prussian war. When these memorials were put up in the 1920s no one wanted to remember that military disaster.

So what was it that took place between France and Prussia 150 years ago? The unfolding events were an astonishing combination of the ancient and modern.

The origins of the war were certainly archaic. The throne of Spain was vacant at the time. It is worth noting that 170 years earlier this very same issue had led to one of the last wars fought by France's Louis XIV, the War of the Spanish Succession. It is also worth recalling that the idea of a German being on the Spanish throne would have brought back memories for France of the Holy Roman Empire under Charles V – who was also King of Spain – surrounding France on all sides in the 16th century.

Even though the world had changed completely, diplomats trod very carefully. The Spanish aristocracy suggested the throne went to a Prussian prince, Leopold of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen. Napoleon III, who had held power in France for more than two decades, saw this as an affront to his empire. Diplomatic tension then rose and Prussia, which was at the time just one of a number of different German states, helped stoke that tension. On July 19th 1870 France declared war on Prussia.

The modernity of the conflict can be seen in how the war itself took place, with the appearance of rapid-firing guns and the unprecedented firepower of artillery, which by now used shells rather than cannonballs. Whether these shells exploded on impact with the ground, as the Prussian army's did, or after a time delay, like the French shells, the result was the same: unprecedented devastation.

Barely a month and a half into the war, which took place in a heatwave, the disorganised and badly-led French troops had suffered defeat after defeat and were forced to fight on French soil. The surrender by Napoleon III and the capitulation of his troops at Sedan on September 2nd 1870 marked the end of this first phase of the war. At the time it seemed the conflict might be over.

But when news of Napoleon III's defeat reached the French capital a new regime was declared, replacing the Second Empire with what later became the Third Republic, and the Government of National Defence was born. This time the French side was driven not by memories of the War of the Spanish Succession, but by the Battle of Valmy of 1792 when French troops fought off an invading Prussian army as the monarchies of Europe came together in a bid to counter Revolutionary France.

In late 1870 Prussian troops and their German allies advanced on Paris and encircled it. The city itself was well defended by the forts that surrounded it, protected behind ten-metre-thick walls and three-metre-deep ditches. But it had to endure a siege that was unprecedented in its history.

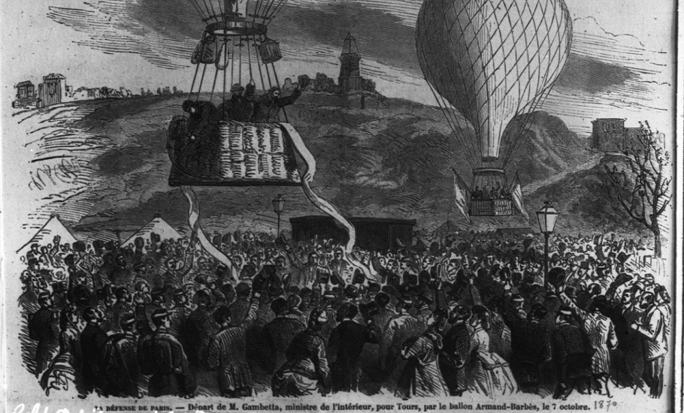

The minister of the interior and war, Léon Gambetta, famously escaped by balloon and at Tours in central western France and then Bordeaux in south-west France he helped to raise a provincial army. Meanwhile the garrison in Paris increased its attempts to break out of the stranglehold that gripped it as the capital endured both starvation and bombardment.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

It all ended in military defeat. On January 18th 1871 Otto von Bismarck's Prussian government, joined by German princes in France's Palace of Versailles, proclaimed the establishment of the German Reich – in other words, the unification of Germany, a major geopolitical event – under the leadership of Wilhelm I. An armistice was agreed. But Bismarck imposed a condition that any peace settlement had to be signed with a representative government.

Elections took place on February 13th 1871 in a France that was ravaged by a cold winter and a quarter of which was still occupied by foreign troops. The voting produced a clear majority of monarchists at the National Assembly, more than a third of whom were from the aristocracy. The new government was headed by veteran politician and former prime minister Adolphe Thiers who began the peace negotiations with the new Reich, culminating in the Treaty of Frankfurt signed on May 10th 1871.

The result was that after eight months of war France lost the region of Alsace and part of the neighbouring region of Lorraine, and had to pay enormous sums in compensation to the victor, which only ended its occupation of part of French soil two years later. In the meantime the Paris Commune was established and implemented unprecedented progressive policies. But that, as they say, is another story.

This has been a brief summary of the war. Much more information can be found in two excellent recent books: 'La Guerre franco-allemande de 1870. Une histoire globale', by Nicolas Bourguinat et Gilles Vogt, published by Flammarion in 2020, and the less erudite but lively L’Humiliante Défaite by Thierry Nélias, published by Vuibert, also in 2020.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

But unlike the commemorations for World War I, which led to a major outpouring of writing, the 1870 war has scarcely troubled the bookshops. There have, though, been a number of regional publications on particular aspects of the local fight put up by soldiers of the National Defence. Often these troops were operating behind enemy lines as irregular soldiers without real uniforms. This was another motif that would be seized on by the Resistance in World War II, with irregular units and groups of partisans set up by the Communist Party under German occupation.

The public events of commemoration that were organised in France (a full list of which can be found here) only attracted a handful of people, even though the Covid epidemic did not help matters. The city of Strasbourg in north-east France organised nothing to mark the 150th anniversary of its bombardment, which had the distinction of being the first to be photographed. Paris did not commemorate its own siege which lasted several months and during which the city experienced its last great famine, symbolised by the eating of two elephants from the Jardin des Plantes zoo.

This is the viewpoint that Genevière Darrieusecq overlooked when she embarked on her commemorative marathon in 2020; the story not just of soldiers but of civilians and how they were affected. Indeed, the impact on civilians was one of the most horrifyingly modern aspects of the Franco-Prussian war; on top of the 50,000 German soldiers and the 140,000 French troops killed, some 450,000 civilians in France perished from hunger, poverty and epidemics because of the conflict.

It was the horror of these burnt-down villages, besieged towns, columns of refugees along the roads and the plight of women – as always the first victims of war and who have been almost completely ignored in historical writings about the 1870-1871 conflict – which the current commemorations in France failed to convey.

'1870 was just one step in a long historical process'

But while France has nonetheless, after a fashion, commemorated the Franco-Prussian war, Germany itself has not marked the event. This is despite the fact that it was during this conflict, and on French soil, that Germany unification was officially proclaimed in January 1871.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

To assess the way the war is viewed in modern day Germany Mediapart interviewed Jakob Vogel, a specialist in 19th century history at Sciences-Po Paris university and director of the Marc-Bloch centre - the Franco-German Centre for Social Science Research - in Berlin.

Mediapart: Is the 150th anniversary of the Franco-Prussian war being commemorated at all in Germany?

Jakob Vogel: That is all a long time ago, a very, very long time ago for Germans today. Everything that took place before 1914 and the atrocities of the 20th century have effectively been forgotten. It's an earlier world, even another world. There are very, very few commemorations and no great memorial ceremonies. In a way that's a good thing: it means that the coming together of Germany and France and the construction of Europe has won.

MP: On January 18th 1871 Emperor Wilhelm I and his chancellor Bismarck, who had just won the war, declared the unification of Germany in a ceremony at Versailles. How can this anniversary not be commemorated in Germany?

J.V.: The 18th of January 1871 is not considered to be the founding date in the history of Germany. The national state created under the leadership of Prussia and the Hohenzollern dynasty has not left only good memories. A recent history of Germany - 'Deutschland. Globalgeschichte einer Nation', by Andreas Fahrmeir, published by C. H. Beck in 2020 – attaches relatively little importance to this date, which is seen as one step in a long historical process. And the war with France was just one of the wars of unification, after those against Denmark (1864) and then Austria (1866).

MP: In the process that you describe, how did the German states accept taking part in a war which at the beginning only concerned Prussia?

J.V.: They followed Prussia as one, without much discussion. In this sense you can say that German unity pre-existed the war. Prussian leadership was accepted by all after the war of 1866. The German crown had already been offered to the King of Prussia [editor's note, Frederick William IV] in 1848, and he refused because he did not want to owe his title to a parliament. In fact the German states were tied by agreements on mutual co-operation, including militarily. The French did not understand this during the crisis of July 1870, as they thought that the southern Germans, and in particular Bavaria, would not follow the Prussians.

MP: What do you make of the commemorations organised in France?

J.V.: I'm struck by the role played by the military in these commemorations. Perhaps this is because the 1914-18 war has been so gone over by historians, and that this distant war is the last opportunity to convey a classic patriotic message? Since the two world wars, the military as an institution has lost a lot of importance in public debate in Germany. It would scarcely be imaginable here that it alone should decide on important commemorations.

In contrast, traditional patriotic culture is certainly still more present in France, as I was able to note when sitting on different scientific committees, for example for the new museum at Gravelotte. Within these environments that are close to the armed forces there is a desire to show uniforms, militaria, to emphasise the role of officers and the high command, to develop patriotic feeling as opposed to providing history as seen from below, such as in current writing about 1914-1918, which adopts the points of view of the infantrymen and wonders how they could have endured it.

MP: The 1914-1918 war has been the subject of a long and violent controversy between historians over the respective importance to be given to forced constraint and nationalistic consent in the infantrymen's acceptance of their fate. Are there comparable controversies in relation to the 1870 war?

J.V.: No, there are no controversies today. It's a tranquil area of research. For example, historians have started to work on the European dimension of the conflict without that provoking any rows.

If there were going to be a debate it would be more about some of the abridged versions of the history of this war. For example, we too often hear how the French were continually planning their revenge after the defeat of 1871. The two world wars strengthened this viewpoint, which was contained in textbooks. But, after a period of adjustment, there was in fact a great deal of co-operation between the two countries between 1871 and 1914, especially over colonisation.

The French sought to copy the Germans who in many areas were held up as a model. You see that for example in higher education, where France imported the Prussian model of universities as places of research. People frequently crossed the border, in both directions. For example, I worked on the case of a group of former [French] soldiers from 1870 who wanted to make a commemorative trip to Germany in 1914. Events prevented it, but what counts is that French people, and moreover former combatants, had wanted to go and see the other side of the border, copying the practices of German associations.

These are the things that one forgets by focussing too much on the nationalistic enthusiasm that once again took over both sides after the war started.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

English version by Michael Streeter