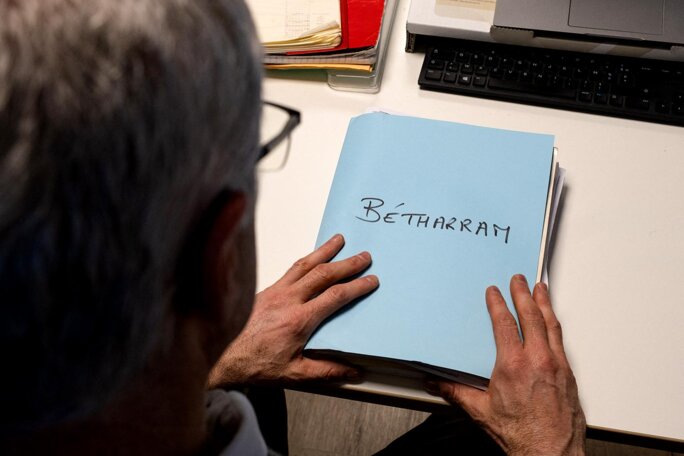

In the unfolding sexual abuse scandal at the Notre Dame de Bétharram private Catholic school in south-west France, there are five François Bayrous. There is the man whose Catholic faith is, by his own account, a pillar of his world view. The father whose own children were educated at the school. The husband whose wife worked at the establishment for many years. The most powerful local elected figure in the region; he was president of the Pyrénées-Atlantiques département or county council (1992–2001), the local Member of Parliament (1986–93, 1997–99, 2002–12), and then mayor of the town of Pau (since 2014). And finally, there is the politician on the national stage; as minister of education (1993–97) and now as prime minister of France.

Five François Bayrous, and a similar number of potential layers of denial that might help explain his woeful handling of the Bétharram scandal over the past three months. This is not about whether the head of the French government has communicated well or poorly. That is not the issue here. The prime minister has lied. In the National Assembly. On television. On the radio. At a press conference, alongside victims of Bétharram.

The prime minister has lied; saying so is not an opinion, it is a fact that should be etched into public consciousness. And it is a fact from which it may now be time to draw some early lessons, as François Bayrou is due to appear before a parliamentary inquiry into the school scandal on May 14th.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

When, on February 11th, he stood up in the National Assembly, one day after Mediapart's revelations, and swore that he had “never been informed of anything to do with violence, let alone sexual violence” in relation to Bétharram, taking care to add a second, indignant, “never” at the end of his sentence, the prime minister knew full well that he was misleading the chamber and, with it, the citizens.

No one, absolutely no one, forced him to make that declaration and to frame it in such a way, adding as he did a threat to sue Mediapart. To this day, we are still unaware of any complaint having actually been filed.

So why did he do it? The head of government did not tinker with the truth in order to shield a state secret. He lied to protect himself. Because, yes, he knew. Obviously he did not know everything about the physical and sexual abuse suffered by generations of children at Bétharram. But he knew enough, while in the various political posts he held, to speak out and to act. The facts are there, and they are stubborn, as David Perrotin and Antton Rouget continue to show in their Mediapart investigations.

What Bayrou knew

It is helpful to go back over a few points in order to grasp the full scale of the lie. As early as 1996, while François Bayrou was serving as France's education minister, and thus responsible for overseeing not just state schools but those private secondary schools such as Bétharram under contract with the state, the local press in his home département was awash with stories recounting the physical abuse suffered by pupils at that establishment. One figure stands out: between 1993 and 1996, news reports cited four perforated eardrums suffered by children who had been hit by staff there. Four perforated eardrums…

Nevertheless in 1996, Bayrou told the local press: “Many Béarnais [editor's note, the collective name for people living in that area of France] have reacted to these attacks [on Bétharram] with a feeling of pain and a sense of injustice. The minister [editor's note, the relevant junior minister at the ministry] has requested all the information he could have requested. All checks have proved favourable and positive. Everything else will follow its own course. The other bodies that need to have their say will do so.” And “everything else” did indeed follow its own course: the courts later convicted a supervisor at the school for acts of violence. The Catholic institution backed the supervisor during the trial, and he was not removed from his post, a decision that provoked little reaction.

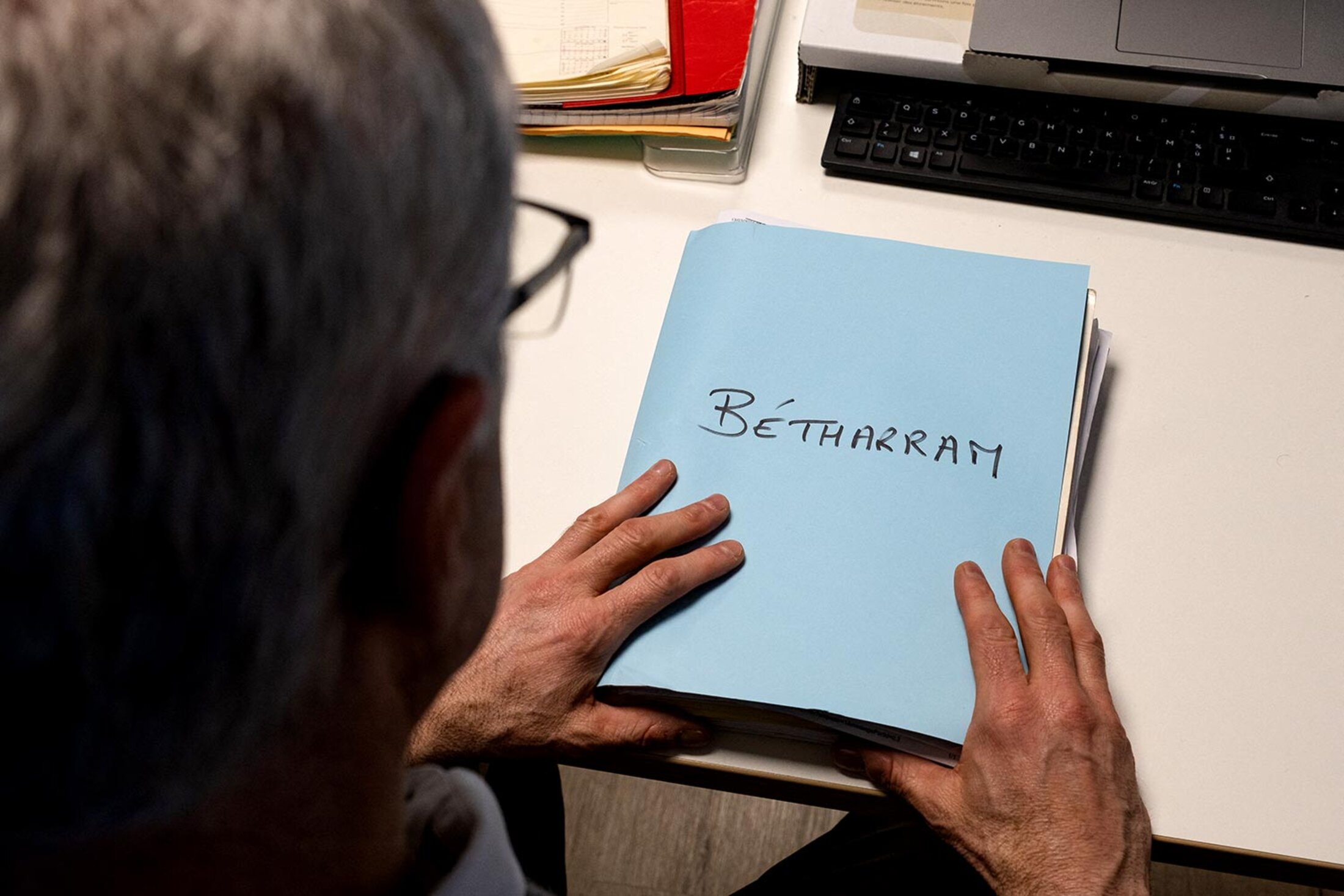

In 1998, François Bayrou’s knowledge of the horrors of Bétharram reached another level. He spent several hours in the nearby village of Bordères at the home of Judge Christian Mirande, who shared with him – at the risk of breaching the confidentiality of the investigation – details of a case the magistrate was investigating involving accusations of rape against a Bétharram priest. The magistrate himself has since described this meeting to the press and, under oath, before the ongoing parliamentary inquiry. This meeting, which François Bayrou initially flatly denied had taken place and only later grudgingly acknowledged, was confirmed last week by one of the premier's daughters, Hélène Perlant, on Mediapart’s broadcast “À l’air libre”.

Two gendarmes involved in the investigations led by Judge Mirande have separately spoken of an intervention by François Bayrou with the chief prosecutor in the case of the abusive priest, though without detailing the nature of that intervention. The prime minister has again denied this, offering in his defence an appeal to authority that is somewhat perplexing: “Judges and gendarmes can be mistaken like anyone else.” Prime ministers can be mistaken too. And sometimes even lie.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

A former teacher at Bétharram also said that she witnessed, in the presence of Élisabeth Bayrou, the prime minister’s wife, who taught catechism there, acts of violence against a pupil. “You could hear the blows. He was yelling, and the child was crying and begging for mercy,” said the ex-teacher. She said she tried to raise the matter with François Bayrou during an awards ceremony at Pau on March 17th 1995. She recalled: “I said to him, ‘Something has to be done about Bétharram, because it’s very serious. I think it’s very, very serious.’ I remember him replying, ‘Yes, people are turning it into a drama.’” And right up until March 2024, others tried in vain to alert François Bayrou.

What he failed to do

None of these warnings stopped the local département council, under the presidency of François Bayrou, from allocating at least one million francs (more than 230,000 euros in today’s money) of public funding between 1995 and 1999 to the institution where his wife worked and where his children studied. Nor did they prevent the town hall at Pau, where Bayrou was mayor, from negotiating a property deal in February 2020 with the Bétharram community. This was the purchase of a building for more than one million euros to house a municipal centre, including facilities for “women in danger”.

In contrast, François Bayrou never once uttered a word of criticism about Bétharram in all those years. Just as he has regularly leapt to the defence of the Catholic Church or its representatives in various cases of sexual violence or cult-like abuse. Instead, it took revelations by Mediapart, and also reports in newspapers Sud-Ouest, La République des Pyrénées and Le Monde, and on France 3 television and Radio France - all following the launch of a judicial investigation that has now gathered more than 200 complaints and victim testimonies - for the Bétharram scandal to become a “Bayrou” affair.

The nauseating approach of the prime minister's office, which seeks to cast press revelations as politically motivated score-settling, will no longer suffice. Of course, there is a risk, however unintended, of fuelling the belief, beloved by conspiracists, that wherever there is child sexual abuse, then prominent local figures must somehow be complicit. But complacency and wilful blindness do exist, as made painfully clear by the current trial of retired surgeon Joël Le Scouarnec in Vannes, Brittany.

The French poet and essayist Charles Péguy once wrote: “One must always say what one sees; above all, one must always, and this is more difficult, see what one sees.” What do we see in the Bétharram affair? We see a François Bayrou who, plainly, could not on his own have changed the course of events in the face of deep collective denial. But we also see someone who was undeniably the public figure best placed to try to do something. He had more access to warnings than anyone else, and to the levers of power that could have been used to try to improve the situation.

By contrast, his failure to act – in particular as head of the département council responsible for child protection and secondary schools – could only have helped strengthen the sense of impunity within the school establishment. What is the point of being such a powerful elected representative if you do nothing in the face of so many warning signs?

Indeed, one now wonders just who the prime minister was addressing on February 5th when he declared that he had never known of the hellish events at Bétharram: the MPs? His children? His wife? His constituents? Himself?

Rather than clinging to a lie that has now become pathetic, and which forces him to adjust his account with each fresh press revelation, would François Bayrou not be better off admitting that he represented a form of denial that was not his alone– but was, nonetheless, also his?

In many other democratic countries such a lie would have long since forced his resignation from office. France is not one of those countries. But the prime minister could at least stop taking the people for fools.

He will give his response at the National Assembly on May 14th.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this op-ed article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter