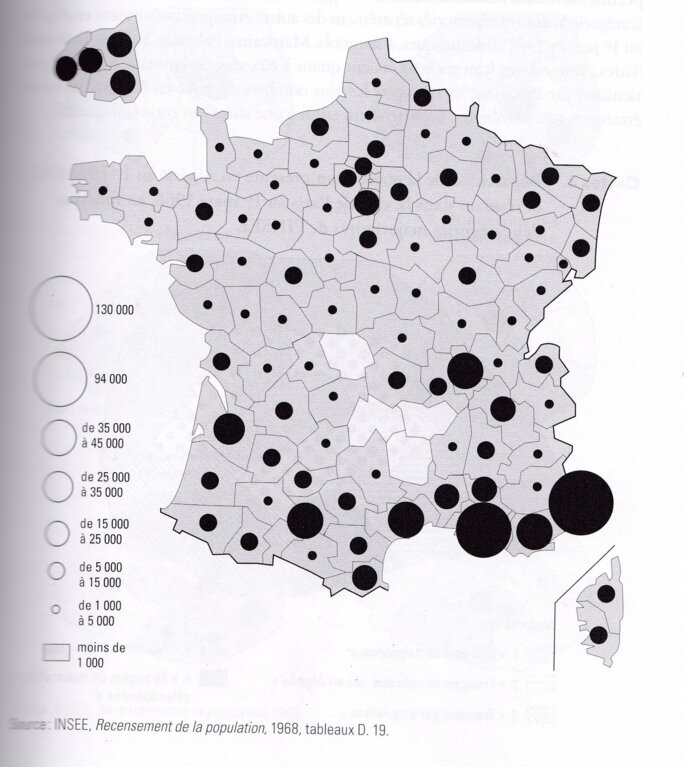

In 1962 the French Mediterranean, from Perpignan to Nice, welcomed a good two thirds of the estimated 800,000 Algerians of French descent – known as Pieds-Noirs - who resettled in France after Algerian independence. Since the 1980s this same stretch of coastline has also been the main bastion of the far-right in France. In the local elections in 1995, for example, the four local communes or towns won by the far-right Front National (FN) - Marignane, Orange, Toulon and Vitrolles - were all in the south.

In local elections two decades later the FN won power in around ten communes in south-east France, while in 2015 Marion Maréchal-LePen, granddaughter of FN founder Jean-Marie Le Pen, came top in the first round of the regional elections in Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur (PACA). Elected FN mayors have not been slow to show their attachment to French Algeria. A monument in “homage to all those fell so that France could live in Algeria” was erected by the FN senator and mayor in Fréjus, David Rachline; there was a public homage by the mayor of Béziers, Robert Ménard, who grew up in Oran, in Algeria, at a monument in the town's cemetery devoted to the far-right paramilitary organisation who fought against Algerian independence, the OAS; and the name of a street in Beaucaire was changed from rue du 19 Mars 1962 – marking the end of the Algerian War – to rue du 5 Juillet 1962, commemorating the massacre of many Pieds-Noirs in Oran on that day.

The question arises, then, as to whether the massive presence of so many French Algerians repatriated from Algeria is one reason for the Front National's growing influence in the French Mediterranean coastal area. To put it another way, if there is such a thing as a Pied-Noir vote, has it been a factor in the way the FN has taken root in that part of France?

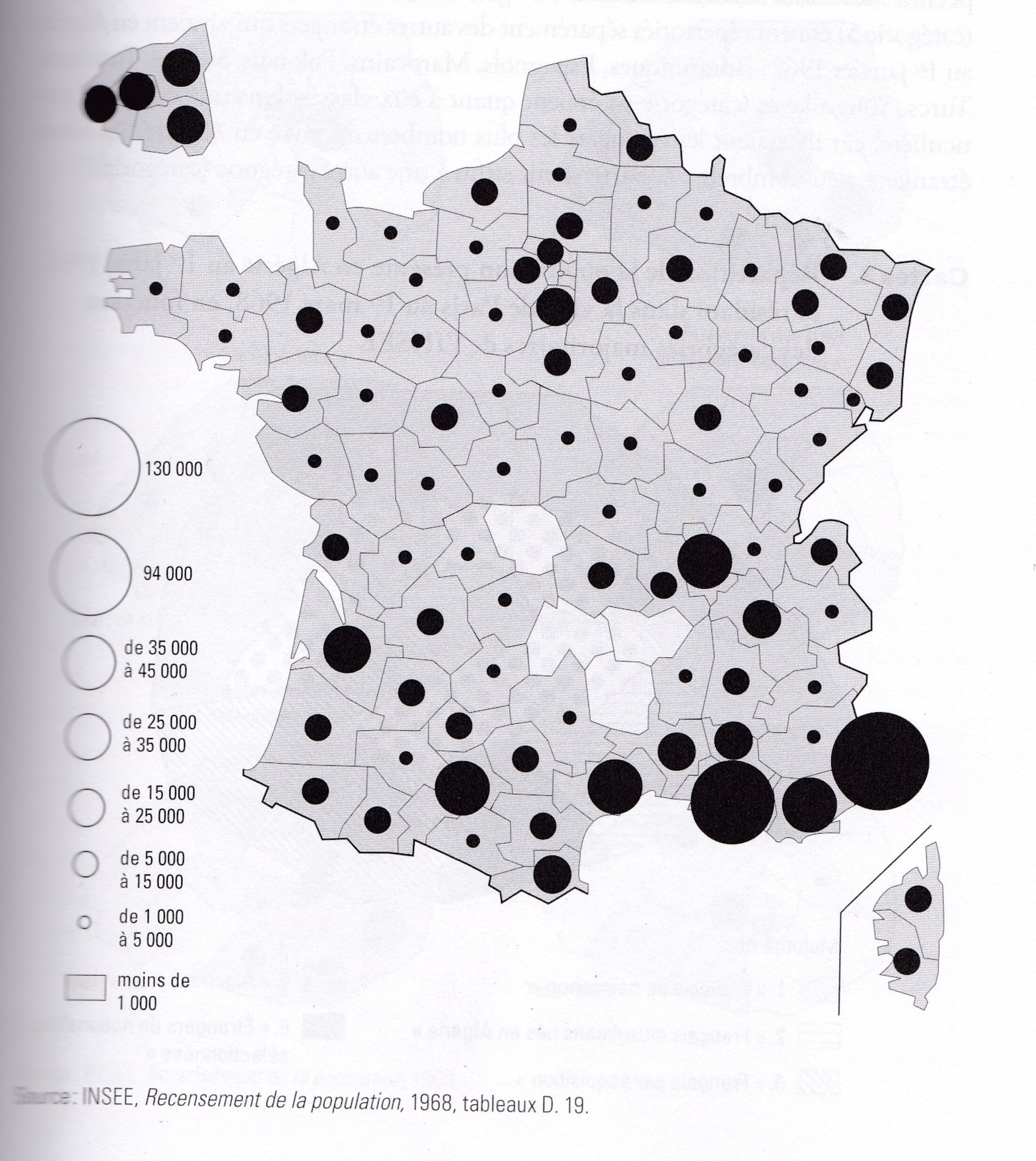

Enlargement : Illustration 2

For historian Jean-Marie Guillon, professor emeritus at the University of Aix-Marseille, there is scarcely any doubt on the matter. “The arrival of people repatriated from Algeria has accentuated anti-Gaullist tendencies [editor's note, opponents of Algerian independence accused President Charles de Gaulle of betrayal when he agreed to end French rule there] on the Right and Left in the PACA region, and has helped reinforce the hard right and the extreme-right there,” he says. He gives two reasons to back his argument: the historic influence of the far right among the French in Algeria, and the central role of former partisans of French Algeria in the emergence of the Front National in the Mediterranean region during the 1980s.

In support of his first argument Jean-Marie Guillon points to a number of historical factors. One is the recurrence of Anti-Semitic riots that led Édouard Drumont – founder of the Ligue nationale antisémitique de France which was active in the Dreyfus Affair – to be elected as Member of Parliament for Algiers in 1898. Another is the development of Jacques Doriot's Parti Populaire Français, the only authentic French fascist party during World War II, and for which Algeria was its third main stronghold after the northern suburbs of Paris and the Marseille area. The third is the almost complete absence of support for the Resistance in Algeria during World War II, coupled with the fact that a large number of elite colonial troops joined the Vichy regime in France between 1940 and 1943. “There is, historically, a long tradition of the extreme right establishing itself in French Algeria, even if it is only manifested in short-lived flare-ups,” says Guillon.

To back his second argument, the historian points to how figures from the old OAS have re-emerged as political officials in the PACA region, and to a lesser extent the neighbouring Languedoc-Roussillon, whether in the non-Gaullist Right or in the Front National. As well as activists of a lesser standing, two symbolic OAS figures in particular have represented the colours of the FN in Parliamentary elections. Pierre Sergent, former leader of the OAS in mainland France who was condemned to death in his absence, was elected MP in the Pyrénées-Orientales département or county in southern France in 1986, while Jean-Jacques Susini, in charge of political and psychological action for the OAS in Algeria and co-organiser of a failed assassination attempt on de Gaulle, received 45% of the vote in the second round of Parliamentary elections at Marseille in 1997.

The Pieds-Noirs adapt their vote

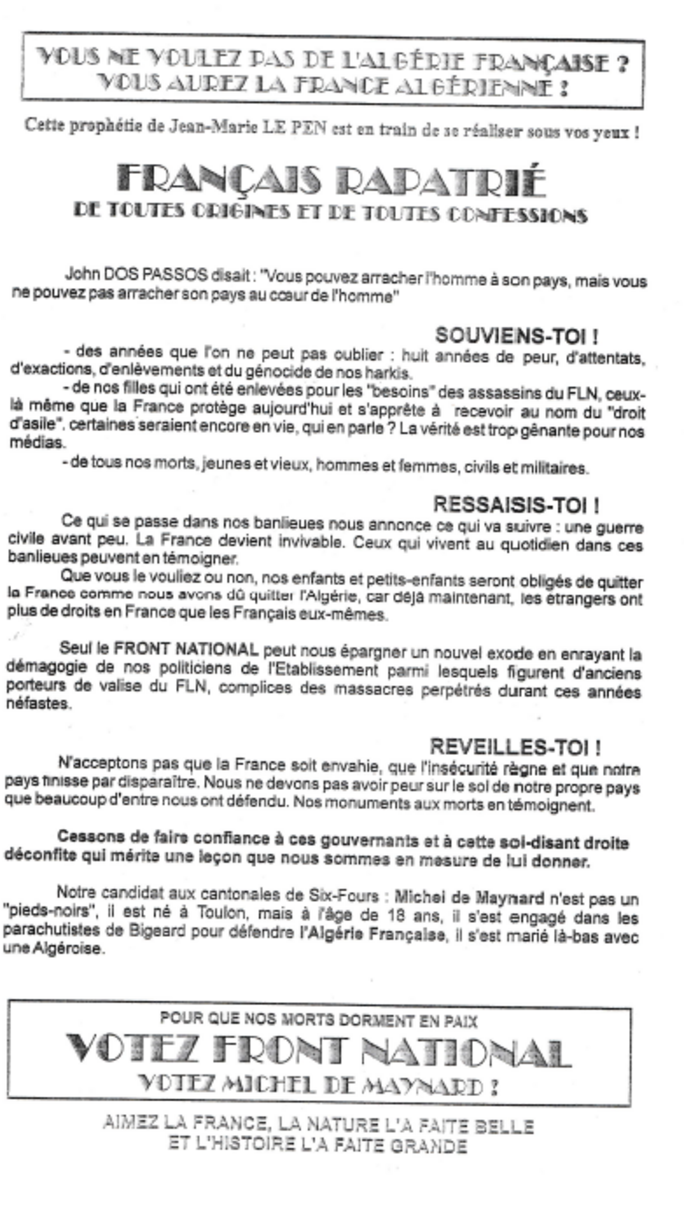

Enlargement : Illustration 3

It was in the presidential elections of 1965, the first vote after the French in Algeria were repatriated in mainland France, that the clout of this new Pied-Noir electorate first made itself felt. The only far-right candidate, Jean-Louis Tixier-Vignancour, the OAS's former lawyer, got his best results in the Mediterranean region. But the support was short-lived.

In the 1974 presidential election Jean-Marie Le Pen indeed received more votes in those départements where the repatriated French Algerians lived; 1.3% in the Herault and the Var and 1.2% in the Alpes-Maritime and the Vaucluse, against his national score of 0.75%. But the level of votes was ten times lower than Tixier-Vignancour had achieved nine years earlier. Should one conclude that the traumas of repatriation had already passed, and that the Pied-Noir electorate had distanced itself from candidates that had defended French Algeria?

“The Pied-Noir electorate was characterised in the 1970s by its skill in using a vote of sanction against political leaders who didn't support their demands: compensation for property lost during the repatriation and, for a small but influential minority of activists, an amnesty for those in the OAS who had been convicted,” explains political expert Emmanuelle Comtat, author of Les Pieds-noirs. Quarante ans après le retour ('The Pieds-Noirs. Forty years after the return') published by Presses de Sciences-Po in 2009. The one constant in the Pied-Noir electorate has thus been its virulent anti-Gaullist stance, but the blurring between Left and Right has faded.

At the presidential elections in 1974 both the incumbent centre-right president,Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, and his successful socialist challenger, François Mitterrand, courted the vote of the repatriated French Algerians. But it was Mitterrand who seems to have picked up more support from these voters thanks to his promise of an amnesty for former OAS leaders and the restoration of their military entitlements and careers. One of the OAS founders, Raoul Salan, called on voters to support Mitterrand.

This electoral promise was kept by 1983, though not without some problems in Parliament. Mitterrand's government had to resort to article 49-3 of the Constitution to force the measure through against opposition from among its own socialist majority. That opposition was led by Pierre Joxe, then leader of the socialist group in the National Assembly, who had served as an officer in the French military in 1961 at the height of the struggle against the OAS, and whose father Louis Joxe had been de Gaulle's minister for Algerian affairs, overseeing the peace agreement to end the Algerian war, and who was thus an OAS target.

It was only in the second half of the 1980s, with the emergence of the Front National, that the old bias towards the far-right re-emerged among Pied-Noir voters. In a wide-ranging study carried out into the 2002 presidential election, Emmanuelle Comtat observed that 52% of electors born in Algeria and resident in the Alpes-Maritimes, Hérault and Isère départements had voted for the extreme-right. The political expert noted: “The Pieds-Noirs who vote for the FN tend to be people who were deeply marked and destabilised by the Algerian War, in particular victims of threats, attacks and violence or people who had lost someone close.” Her study showed that the Pied-Noir electorate is massively on the Right of the political spectrum. Asked to place themselves on a scale of 1 (far-left) to 7 (far-right), only 12% put themselves on the left of the scale, against a national average of 40%.

The latest study of the Pied-Noir vote, carried out by the political research centre at the Sciences-Po institute, CEVIPOF, was carried out in 2012. Fifty years after Algerian independence, voters who define themselves as Pied-Noir represent some 1.2 million people, still mostly concentrated along the French Mediterranean: they represent 15.3% of voters in Languedoc-Roussillon and 13.7% in PACA, compared with under 3% in Picardy in the north and Brittany in the west. The right-leaning tendency is still apparent: the current FN president Marine Le Pen was top among those who were intending to vote among the Pieds-Noirs with 28% (8.5 points more than the national average), followed by the right-wing Nicolas Sarkozy at 26% (3.5 points above the average) on the same score as socialist François Hollande (3 points below the national average).

But CEVIPOF underlined the fact that “the greater presence of the Pied-Noir community in Languedoc-Roussillon and PACA only partially explains this phenomenon … Even without the Pieds-Noirs, these two regions would still vote more for the Front National than other regions, the presence of the Pieds-Noirs simply reinforces this tendency”. Meanwhile Emmanuelle Comtat highlights the fact that “the Pied-Noir community is disappearing. Those who were aged 30 at the time of the repatriation are now 84 and we know that electoral participation diminishes rapidly with very old age”.

All the studies show, in fact, that the total electorate descended from those who repatriated from Algeria, estimated by CEVIPOF as a total of 3.2 million people declaring a French parent or grandparent from Algeria, vote broadly in line with the rest of the electorate. It is no longer Marine Le Pen but François Hollande, with 31%, whom the descendants of the Pieds-Noirs put at the top of the list of who they were going to vote for in 2012. Unlike the former Harkis – French Muslims who supported the French in Algeria and many of whom were repatriated to France after 1962 – whose children often carry on the struggle by getting involved in associations, the descendants of the Pieds-Noirs have for the most part turned the page on the traumas of the 1962 exile.

The battle between Right and far-right

In summary: a Pied-Noir vote marked by a preference for the anti-Gaullist Right and far-right certainly did exist. But today it is no more than a residual vote, and will without doubt have disappeared by the presidential election of 2022. This leaves the question of why so many politicians in the French Mediterranean area so overtly court what seems more and more to be a mythical Pied-Noir vote.

For example, the town hall at Aix-en-Provence has donated land to build a new national museum in memory of the French in North Africa; the right-wing mayor of Nice Christian Estrosi, newly-elected president of PACA, inaugurated a monument to the memory of the French in Algeria on the promenade des Anglais at Nice in 2012; while the right-wing mayor of Carcassonne, Gérard Larrat, attended the 40th congress of the Cercle algérianiste, a group which seeks to keep alive the memory of the French in Algeria. Moreover, the centre-left mayor of Montpellier, Philippe Saurel, recently scrapped plans for a new museum devoted to the French in Algeria, in which two million euros had already been invested, but which did not have the good fortune to please the more hard-line Pied-Noir organisations.

In Perpignan, meanwhile, under right-wing mayor Jean-Marc Pujol, flags are lowered to half-mast each March 19th, to mark the end of the Algerian war and with it French involvement in Algeria. And a number of large towns and cities such as Aix-en-Provence, Perpignan and Nice still have assistant mayors in charge of repatriation, even though one might question whether, more than half a century after the repatriation, this section of the population still needs specific support in this way. These are just a few of the examples. “Politicians like to believe that community votes exist even though political science shows that they are most often myths,” says Emmanuelle Comtat.

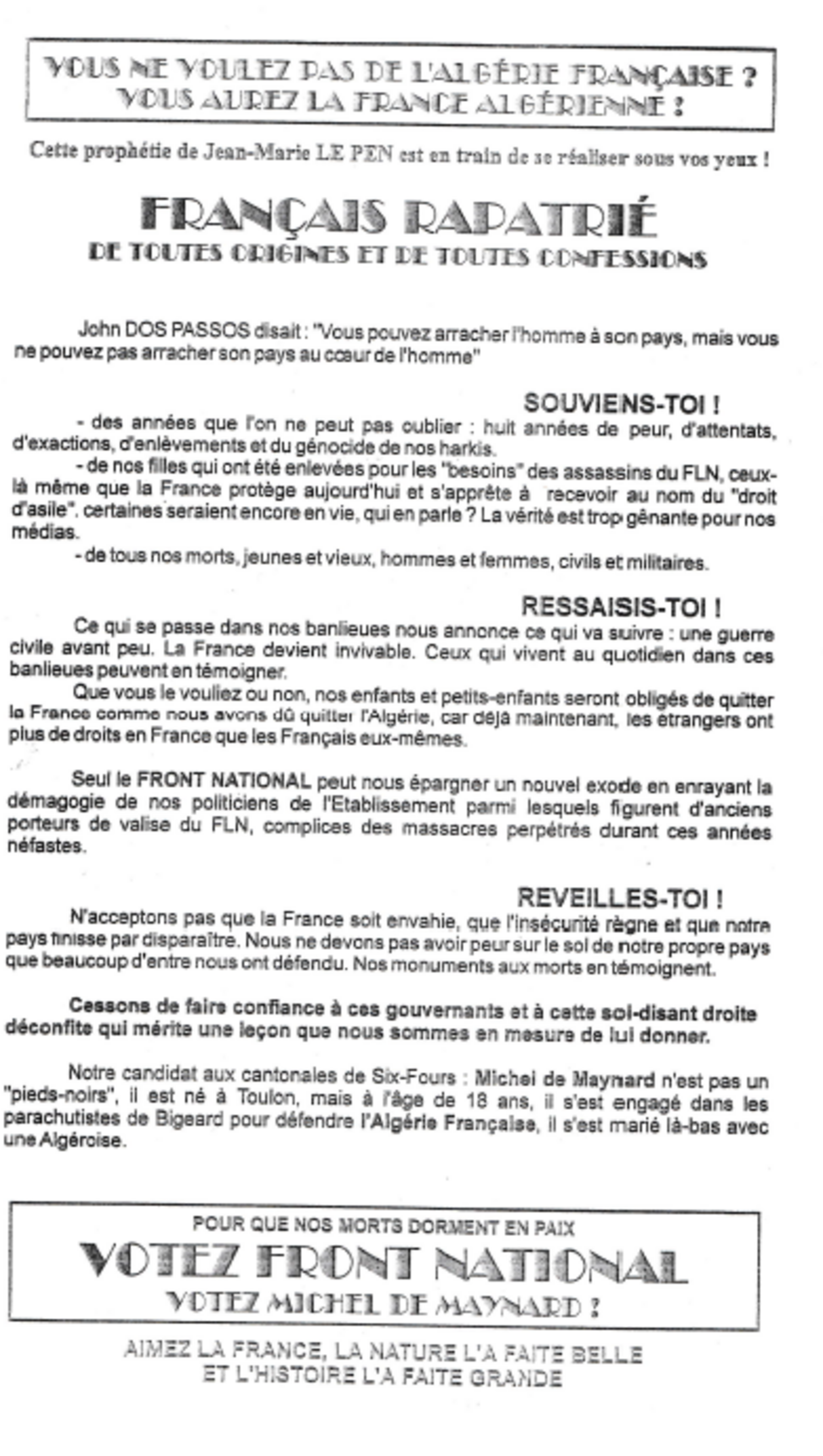

Enlargement : Illustration 4

But politics is also about myths, drawing on symbolic figures or key-note episodes in history. In this respect the Right has succeeded in a master stroke since the second presidency of Jacques Chirac (2002 - 2007). After Chirac's re-election in 2002 nine right-wing MPs from the southern départements of Bouches-du-Rhône, Alpes-Maritimes, Hérault and Var put forward a bill on behalf of French Algerians repatriated in the 1960s. The initiative culminated in the law of February 23rd, 2005 in which the French nation formally “recognised” the role and contribution of the Algerian French. After a lengthy controversy article 4, which stated that “school programmes are to recognise in particular the positive role of the French presence overseas, particularly in North Africa” was repealed by the government. But a taboo had been lifted; the taboo that had, up to then, prevented Pieds-Noirs from voting for the political inheritors of Charles De Gaulle, such as Chirac.

There then followed a ferocious battle between the Right and the far-right to win the support of the Pied-Noir community, which ended with the former gaining at the expense of the latter. “The ideological radicalisation of the Right on questions of identity and security helped closer ties between the associations speaking in the name of the repatriated people and the Gaullist Right,” says Emmanuelle Comtat. The emergence of the so-called 'popular right' within the right-wing UMP (now Les Républicains) in 2012 was one of the aspects of this new political conquest. Some 40% of MPs from this tendency were elected in constituencies in the Mediterranean area, and a quarter of them come from families of people who were repatriated or former activists on behalf of French Algeria. Leading figures in this category include Lionnel Luca, MP and mayor of Villeneuve-Loubet, and Michèle Tabarot, an MP, mayor of Le Cannet, and daughter of a former OAS activist.

“The disappearance of the Gaullist dinosaurs … and the gradual removal of their pro-Chirac inheritors left the way open for a new generation which did not experience the clash with the OAS and which had the firm intention of rehabilitating our colonial past and above all French Algeria,” observes historian Alain Ruscio in Nostalgérie. L'interminable histoire de l'OAS ('Nostalgeria: the never-ending story of the OAS'), published by La Découverte in 2015.

But this takeover bid by the Right aimed at a largely mythical Pied-Noir vote comes at a time when the organisations that claim to be representing the Pied-Noir memory are inexorably losing influence as their members age. In the 1980s there were around 1,000 such organisations, against 600 today, and many of these are local groups based in villages, town districts or secondary schools that have little political involvement. “Public opinion can often be boiled down to 'opinion made public' through the expression of a dominant sub-group inside the larger group, namely highly-active associations,” explains Emmanuelle Comtat. She underlines the fact that, according to her 2002 study, just 5% of people repatriated from Algeria were members of an association claiming to represent the material or moral interests of the Pieds-Noirs.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter