The Covid epidemic follows its tragic course in France as in other countries. This weekend, from January 2nd, a tougher 6pm curfew has been imposed in large sections of the east and south-east of France, in the regions of the Grand Est, Bourgogne-Franche-Comté, Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur and Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, where there are currently the most cases.

At the moment the epidemic has more or less plateaued with the number of cases nationally rising only slightly. But the country's Covid-19 Scientific Committee – which advises the government on how to handle to epidemic – says that an “uncontrolled” increase in the number of cases is “possible” once the Christmas and New Year holidays are over. A salutary warning comes from across the channel, where the United Kingdom has been recording more than 50,000 cases a day and where the number of Covid hospitalisations in Britain is higher than in the first Covid wave in the spring as a new variant of the virus spreads rapidly.

Faced with the threat of the virus, most countries have placed an emphasis on the most powerful form of prevention in the history of medicine: vaccines. But in this global push for vaccination France has – so far - been just about the only country to hesitate.

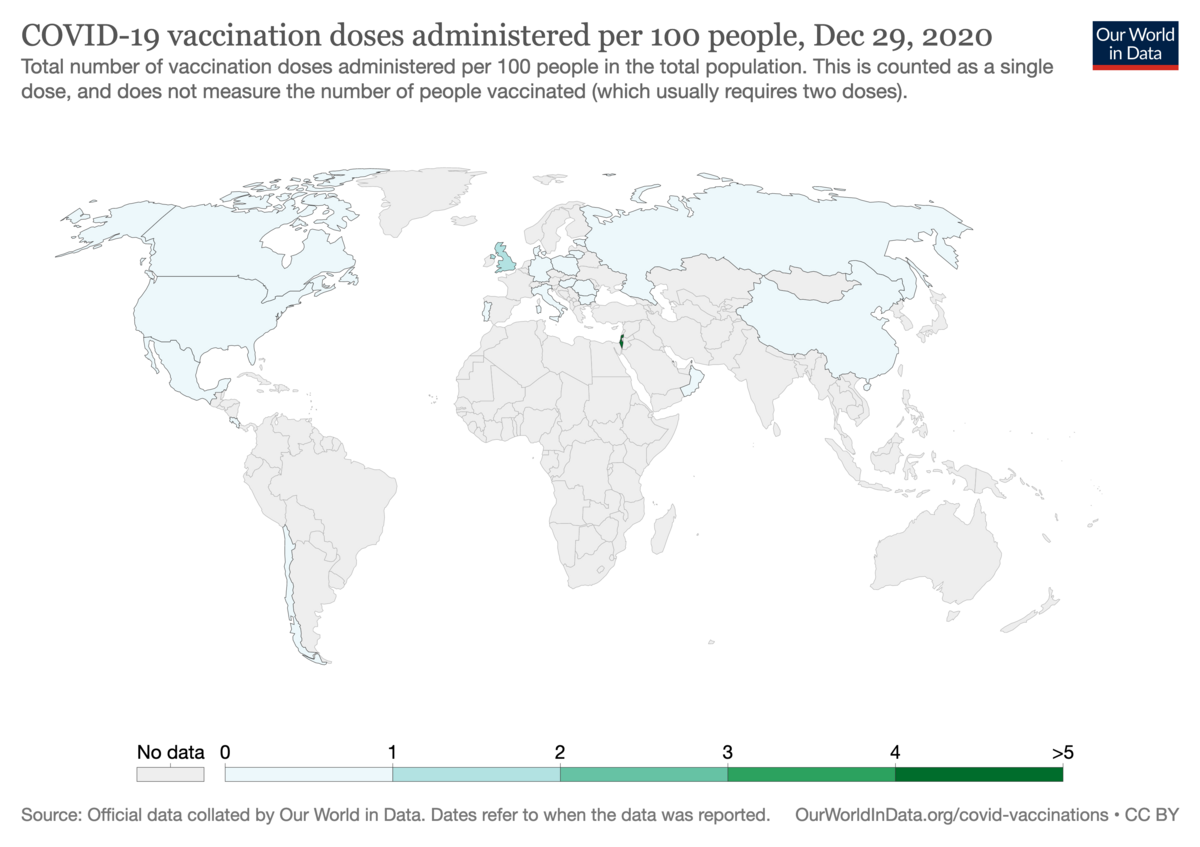

The vaccination figures so far tell their own story. According to the Our World in Data website, the United States have vaccinated more than 4.2 million people, China 4.5 million, the UK just under a million and Canada 1.1 million. In terms of the proportion of people vaccinated, Israel is ahead with around one million or 12.59% of the population already given the vaccine amid plans to increase the speed to inject 150,000 citizens a week. Israel will doubtless be the first country to discover the last great unknown about the vaccines: on top of being effective at preventing someone from getting Covid-19, will it also stop transmission of the virus?

The countries of the European Union have also started their vaccination campaigns, though at different speeds. Germany, which is focusing on vaccination centres, has already vaccinated 238,000 people, Portugal close to 27,000 people and Denmark 32,000 people, while Poland has vaccinated 47,000. In contrast, as of January 2nd France had managed just 352 vaccinations across 23 care homes for the elderly.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The French government has been cautious because it believed this was the best way to deal with public opinion, which has shown a marked reluctance about getting vaccinated. This is nothing new; an international study in the medical journal The Lancet on trust levels over vaccines carried out in 149 countries between 2015 and 2019 put France among the most mistrustful in the world, alongside Mongolia and Japan.

The Covid-19 crisis has only added to this wariness. According to a BVA opinion poll conducted in 32 countries and published by the French Sunday newspaper the Journal du dimanche (JDD), just 42% of French people polled are willing to be vaccinated against this new virus. France is the third most mistrustful country in the poll behind Serbia and Croatia. By contrast, 91% of Chinese people questioned said they were prepared to get vaccinated, 81% of British people, 66% of Americans and 65% of Germans.

Indeed, the roots of French mistrust over vaccines stretch back over a decade, as explained further below.

Faced with this reticence, the French government has been taking its time. The first vaccinations at care homes for the elderly - which began on 27 December 27th – allowed the authorities to test the campaign, which is due to be rolled out fully in care homes from January 18th. Health minister Olivier Véran recently told the JDD newspaper that he did not want to act “in haste”. He said: “I don't want to cut corners on any of the principles to which I have committed.” These principles include the fact that the vaccine will not be obligatory, the need to obtain a person's consent and the importance of the vaccine's traceability in the patient's medical file and via the website 'Vaccin Covid', which is hosted by the state health insurance system. This is where any undesirable side effects will be flagged up.

Yet the slowness caused by this cautious approach has apparently angered President Emmanuel Macron. In private comments reported by the JDD newspaper, the head of state has described the campaign as moving at the “speed of a family stroll”. He apparently complained that the current progress of the campaign is “not what the situation demands or what the French people demand” and continued: “I am waging war morning, noon and night and I expect the same commitment from everyone.” The situation “has to change quickly and profoundly and it's going to change quickly and profoundly”, he is said to have added.

This explains why on December 31st health minister Olivier Véran changed his tone and announced that the vaccination campaign would “be stepped up”. From this Monday, January 4th, the campaign will not just target care home residents and the vaccine will be given to health professionals aged over 50, while from the start of February “vaccination centres” are to be opened for people aged 75 or over.

It is true to say that rolling out the BioNTech/Pfizer vaccine is a painstaking and complex process. It has to be kept in specially-bought freezers that are capable of producing temperatures of -80°C and which have been stationed in various locations around the country. When a pharmacy or another establishment takes delivery of a batch of vaccines it can be kept in a normal fridge for five days. Each vial contains five doses. Once the vial is opened the doses must be injected within five hours. The whole process is set out in a 45-page guide to 'phase 1' of the campaign, aimed at care homes.

“It's a lot of work, major logistics, lots of precautions are taken and traceability is important,” said geriatrician Christophe Trivalle, head of service at the Paul-Brousse hospital Villejuif, south of Paris, who is in charge of preparing vaccinations there.

Yet with all the precautions that are being taken, there is a risk that the government is seen as losing sight of the seriousness of the crisis, and of losing sight of the public's desire to get out of it as fast as possible. While it is true there are widespread worries about the vaccine, public opinion can turn very quickly.

Indeed, after a period of uncertainty, there has been a series of good news released about the BioNTech/Pfizer vaccine, which is an RNA-based vaccine. The clinical trial, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, shows an effectiveness of 95% in preventing Covid. The three-month trial involved 43,000 people split into two groups, one of which took the vaccine and the other a placebo.

So far the results on the short-term side effects have also been very encouraging. Already close to 4 million people in the world have been vaccinated with Comirnaty (the commercial name of the BioNTech/Pfizer vaccine). Several allergic reactions have been recorded, including anaphylactic shock. As a result people with high allergies have been excluded from the vaccine programme.

The other side effects that have been identified seem benign and are common in vaccinations: a red blotch where the needle goes in, headaches, shivering and a temperature. The medium and long-term side effects are not yet known of course but they are very rare in other vaccines.

In the British and American media the issues of the vaccine's safety has largely been overtaken by other issues: production capacity, the fairness of distribution around the world and who should be given priority. In the United Kingdom front-line carers have already expressed their frustration at not getting vaccinated more quickly.

In the United States senior political figures have been vaccinated, including president-elect Joe Biden, and his future vice-president Kamala Harris, while on the Republican side vice-president Mike Pence has also been vaccinated.

'There's really been no rush'

The vaccination programme in France began last week on a very small scale. At the Paul-Brousse hospital in Villejuif the occupants of a long-term ward are supposed to be vaccinated this coming week. But the number of people will be limited as the vaccination is not recommended for patients who have already contracted Covid-19.

“The virus has had a devastating effect,” said geriatrician Christophe Trivalle. “In this unit 80% of my patients have already had Covid during the first or second wave. Eleven elderly people were earmarked for vaccination. One of them is contraindicated because of allergic risk. Two refused vaccination, three prefer to wait, and five agreed to have it. It's very often the family contact or the guardian who have taken the decision, as these elderly people have cognitive disorders.”

The geriatrician has his own analysis of how people view the vaccine. “There are those who are against it straightaway, those who are for it straightaway and those who prefer to wait. It's a similar situation with the carers and even the doctors. Those who are at risk of Covid can also get vaccinated but no one has come forward to the workplace doctor. There's really been no rush, but when the process is started there will doubtless be some impatience,” he predicted.

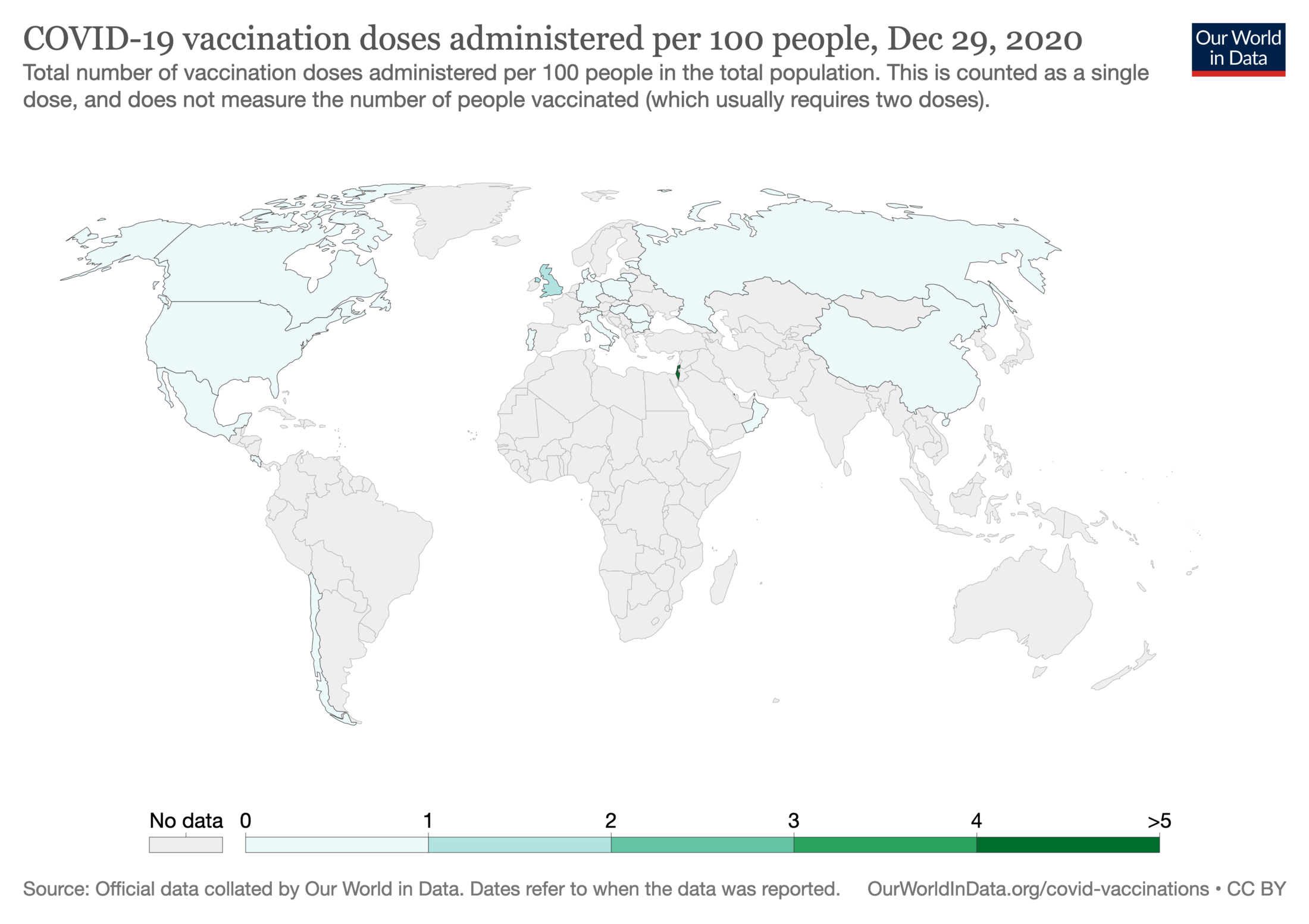

Enlargement : Illustration 2

One anecdote illustrates how polarised French society is over the vaccine issue. The images of France's first recipient of a vaccine, Mauricette M., a resident at the René-Muret care home in Sevran, north-east of Paris, has already divided opinion on social media. The elderly woman, who was naturally overawed by the “pool” of accredited journalists and the cameras, was astonished when she saw the needle. As she wore a mask her words were hard to understand; some thought she said “ah, have to have a vaccine” while others thought she said “have to put up with it”.

As a result some people queried whether Mauricette had really given her consent, even though she also said very clearly “Ok, go on, no panic!” The hospital authority, the Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP), to which the care home belongs, said that it had followed national recommendations. These include a need for “clear information” to be given to the resident and their family and a medical consultation to be sure there are no contraindications, during which the person's consent is obtained. “Everything is indicated in the medical file,” said AP-HP.

However, some on social media raised doubts over Mauricette M.'s ability to understand what she was doing. Ève Guillaume, who is the director of a different care home in Sevran, was not present at the vaccination event. But she said that during a visit by journalists to her own public sector establishment she had faced questions over the capacity of residents to understand what they are agreeing to “even though we judge them to be responsible for their actions and their decisions”. She added: “Elderly people are often treated like children.”

The care home boss could hardly disguise her impatience for the vaccination campaign to start. “We took part in the trial exercise organised by the regional health authority, we're ready, but we still don't have a vaccination date,” she told Mediapart. “The vaccine carries the hope for a return to normal. We were badly hit by the first wave, 20% of our 79 residents died of Covid. It's tough, we're doing crisis management on a daily basis.”

But Ève Guillaume also highlights the lingering doubts that exist over the vaccine, doubts that she says involves “around a half” of her residents. “Some, who said they were willing, are starting to have doubts because their families are telling them about what they've read on social media. It's difficult to deal with fake news. A majority of the carers are against, they talk to us about 5G microchips,” she said, a reference to the conspiracy theory about 5G mobile phone signals helping Covid to spread.

“The majority of families who call us tell us they are opposed to the vaccine,” said the care home boss. “When a resident is at the end of their life, I understand that one should offer themlow-key care. But when they have months or years ahead of them, their refusal raises questions for me.”

Ève Guillaume has herself volunteered to have the vaccine, as have the home's doctor and nursing managers. “We could get the doses that are not used. That seems fair enough to me, we are working with people who are very vulnerable to the virus,” she said.

Dr Gaël Durel, president of the care home doctors association the Association Nationale des Médecins Coordonnateurs en Ehpad, said that the vaccination raises major ethical questions. “Many people still doubt the seriousness of Covid,” he said. “We have to remind them our residents have a 25% chance of dying from Covid. The most difficult part will be obtaining the consent of families, who might be divided. The Comité Consultatif National d'Ethique [editor's note, which advises the French government on medical ethical issues] suggests that we pose the question in this way: when they were in full possession of their faculties, was your relative in favour of vaccination, of medical innovation?”

Dr Durel insisted that there would be “no discrimination against residents who are not vaccinated”. But he said: “The drug companies are not philanthropists, the first served will be those who ask first and loudest. If there are lots of refusals in January we don't know when there will be a catch-up session. Let's seize the opportunity. As a doctor in a care home my responsibility is to enable elderly people to live well for several months or years.”

In common with others, Dr Durel did express doubts at the start of December about the vaccines “because the drug companies had at the time only published press statements. Since then the trials have been come out, I've discussed it with specialist colleagues and I'm convinced. I'm top of the list of volunteers for the vaccine, but I'll be the last if others want to go ahead of me.”

But what explains the deep wariness over vaccines in France, the country of Louis Pasteur, the 19th century scientist renowned for his pioneering work on vaccination? Psycho-sociologist Jocelyn Raude, of the public health educational institute the École des Hautes Études en Santé Publique (EHESP), told Mediapart that for around a century from the end of the 19th century there was a “very strong” political and cultural consensus in France about the value of vaccines. “Modern vaccination and the figure of Pasteur were sources of national pride,” he said. “Vaccines could even be seen as an instrument of soft power for France.”

One episode that perhaps began a change of mood in France was the vast campaign of vaccination against hepatitis B for both children and adults from 1994. There were some fears of a link between this vaccine and a small increase in the number of cases of multiple sclerosis, even though subsequent studies found no connection. Nonetheless, the controversy was enough to persuade the health minister in 1997, Bernard Kouchner, to stop the vaccination campaign in French schools. Instead, responsibility for giving the hepatitis B vaccine was handed to family doctors. “That fuelled the legitimate concerns and suspicions that parents had,” said the historian and philosopher of science Annick Opinel, a researcher at the Institut Pasteur and member of the vaccination technical committee on the Haute Autorité de Santé health authority whose recommendations are helping to guide the vaccination campaign. “It was a kind of abandonment of public health.”

However, up until 2005 around 90% of French people were still very supportive of vaccines. The key change came over the state's handling of the 'swine flu' A/H1N1 pandemic of 2009 and 2010. Though this flu was quickly found to be less dangerous that first feared, there was a call for a global vaccination campaign which largely failed. The French state itself bought 94 million vaccine doses to provide 75% of its population with two doses. But in the end the order for more than 50 million was cancelled as only 5.36 million French people received one dose and only 563,000 were vaccinated with two.

The campaign was subsequently criticised on economic grounds as a waste of money. This was also the time when social media was starting to play an important role and the vaccination campaign was targeted by conspiracy theorists and those who were concerned about the purpose and content of the vaccines. “We also saw the emergence of vaccine sceptics from the medical world … who raised questions about some additives in vaccines, in particular aluminium salts. This talk was picked up by the mainstream media...” said psycho-sociologist Jocelyn Raude.

Trust in vaccines in France quickly began to fall. “We saw the number of people who were hesitant about vaccinations climb by 10% to 40%,” said Jocelyn Raude. The situation was not helped by the Mediator weight-loss drug scandal which further eroded public confidence in the medical world. “We saw the uptake of flu vaccines fall from 66% to 50% among elderly people,” said the psycho-sociologist.

The handling of the swine flu crisis had a traumatic impact on France. This helps explain why some in authority dismissed the first reports of the Covid outbreak in China as a “little flu”. And at the beginning of the outbreak in France the authorities initially ruled out the creation of vaccination centres. Health minister Olivier Véran even referred to “vaccinodromes”, the term employed by opponents to mock the use of vaccination centres in the 2009-2010 swine flu outbreak.

Jocelyn Raude says that vaccines have become a divisive subject. “We are seeing a politicisation of the vaccine issue: those who are close to the parties of government support it more; those who are close to the extremes, on the right and the left, are mistrustful. It's become an indicator of one's identity. What's also very striking in France is to see the low level of trust towards medical and health institutions,” he said. “You don't see that in other countries.”

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

English version by Michael Streeter