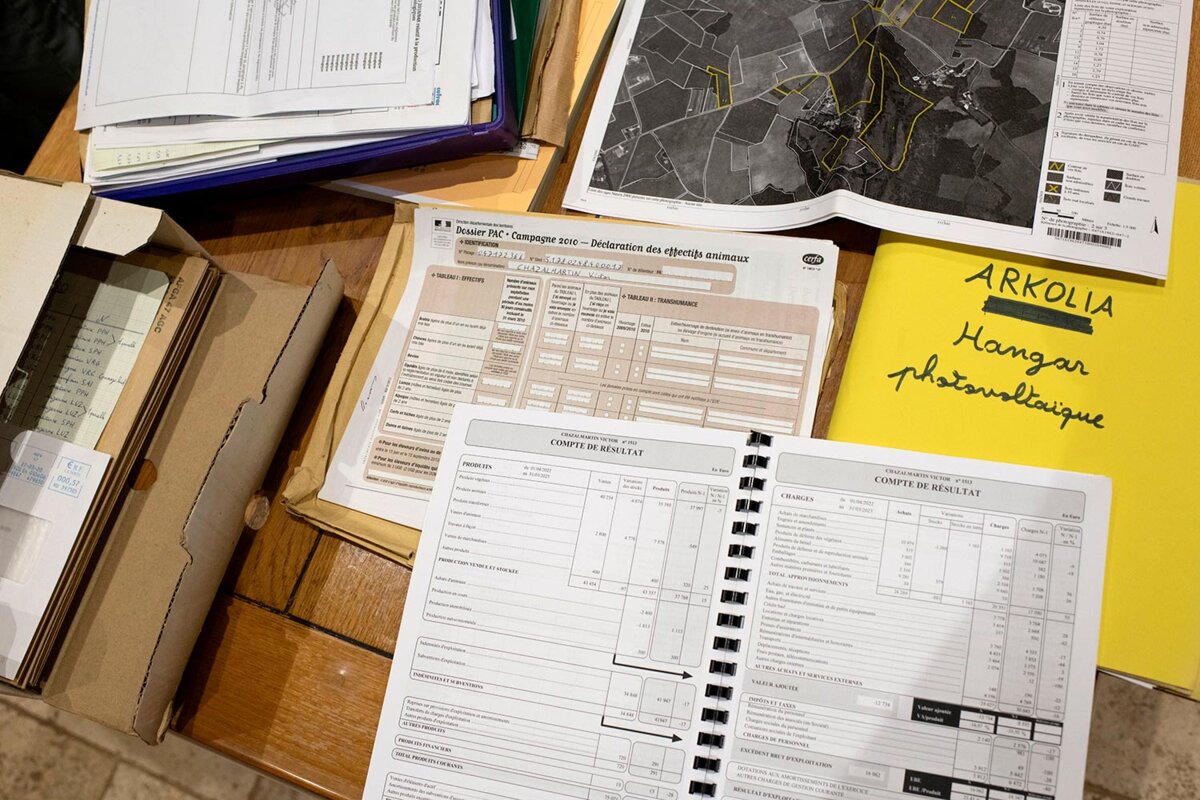

Karine Moinet gets out her thick, bulging ring-folders and spreads them out on the kitchen table, confident in the impact this will have. She has carefully preserved all the farm's records ever since she and her husband Pierre set up business in 2005. “Because you never know. The [payment agency] Agence de Services et de Paiement (ASP), which monitors our farms, has already asked for proof of our seed purchases for the last six years,” Karine Moinet points out.

The farming couple receive 30,000 euros in subsidies a year from the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). Without this public money they could not pay themselves incomes of 1,000 euros and 1,200 euros a month. They run an organic dairy farm with a herd of 50 cows, which are fed solely on grass and fodder from their 100-hectare (247-acre) farm at Monbahus in the south west of France.

“We can't complain,” say the couple. “A half of all farmers live on RSA [editor's note, income support] and we've been through that. What's good about this life is the freedom. But with the CAP it's like wearing an electronic tag,” they say.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Victor Chazalmartin, also an organic dairy farmer, runs a herd of 30 cows on 54 hectares. A member of the Confédération Paysanne farming union – which represents smaller scale farmers – he insists that simplifying paperwork is a “demand of all farming unions”. According to him “the admin is just gradually increasing”.

He would like to show Mediapart the digital portal Telepac, which handles CAP payment issues. But, however hard he tries, he cannot remember his password because “you have to change it every six months”. An additional problem is that here in Lascombes, a small community near the south-west town of Villeneuve-sur-Lot which sits in the middle of rolling hills and plunging valleys, the 4G services Victor has used for his internet connection comes and goes according to the direction of the wind.

“The internet went down in the middle of our declaration,” the farmer sighs. A month ago he was finally connected via fibre optic cable. And though the internet connection is still slow, he jokes: “It's certainly a lot more efficient that all the simplification measures announced by [prime minister] Gabriel Attal.”

Yet there is nothing to laugh about when it comes to the farm's end of year accounts, which Victor's wife Clémence in fact angrily describes as “disgusting” - she is a beautician and the family largely relies on her income to survive. The accounts for the farm from April 1st 2022 to March 31st 2023 show an outlay of 75,000 euros and earnings of 5,380 euros. “Any business that produces such accounts closes,” Victor Chazalmartin acknowledges. Today he is earning around “400 euros net a month”.

The 38,000 euros a year he gets in subsidies from the CAP is just about enough to keep his head above water. “These subsidies are becoming more and more complicated to obtain,” he says. He believes this is “clearly being done to discourage farmers from getting them”.

Satellite checks

All three farmers are subject to the separate obligations that apply to livestock farming and arable farming. They all grow grass for their animals but also produce cereals – wheat, maize and alfalfa – as well as melons and garlic in the case of Victor Chazalmartin. They also have to conform to organic certification rules. “But we chose that, we take that more willingly,” Victor explains.

For CAP declarations the farmer must map out their plots of land right down to the “buffer zones alongside waterways, hedges, ponds and lakes,” says Agnès Chabrillanges, director of the Chamber of Agriculture for the Lot-et-Garonne département or county where these farmers are based.

The farmers then have to declare, down to the nearest are (which is a hundredth of a hectare or 0.0247 acres), the crops that they plan to grow on those plots. They must also comply with the rules on crop rotation. “The farmer has to state the previous crop, the date of sowing and land type, to which different dates apply according to the type of crop,” says Agnès Chabrillanges. “They must also stipulate the areas left fallow.”

“That all looks very good in an office,” sighs Victor Chazalmartin. “But in reality you have the weather. When it's very dry you can't work the land. And this autumn we had 500mm of rain and couldn't plant wheat. We can't keep to their timetable.”

Since 2023 the accuracy of such declarations has been checked by satellite images. “If the [local state agency] Direction Départementale des Territoires (DDT) detects an anomaly by satellite then the [payments agency] Agence de Services et de Paiement (ASP) contacts the farmer. They must justify what they've done and send a photo to prove they've acted in good faith,” says Agnès Chabrillanges at the Chamber of Agriculture.

Karine Moinet gives an example. “If we crop earlier than planned they see it on the satellite photos and ask us for an explanation,” she says.

Farmers also have to declare their muckspreading and liquid manure spreading schedule – and in the case of non organic farmers their use of chemicals – which has to state the amounts that will be used, based on “an analysis of the land, in particular its nitrogen concentration”, says Victor Chazalmartin.

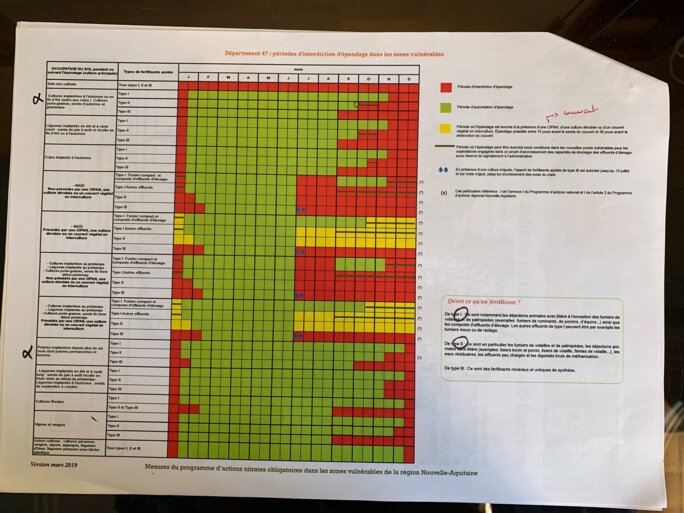

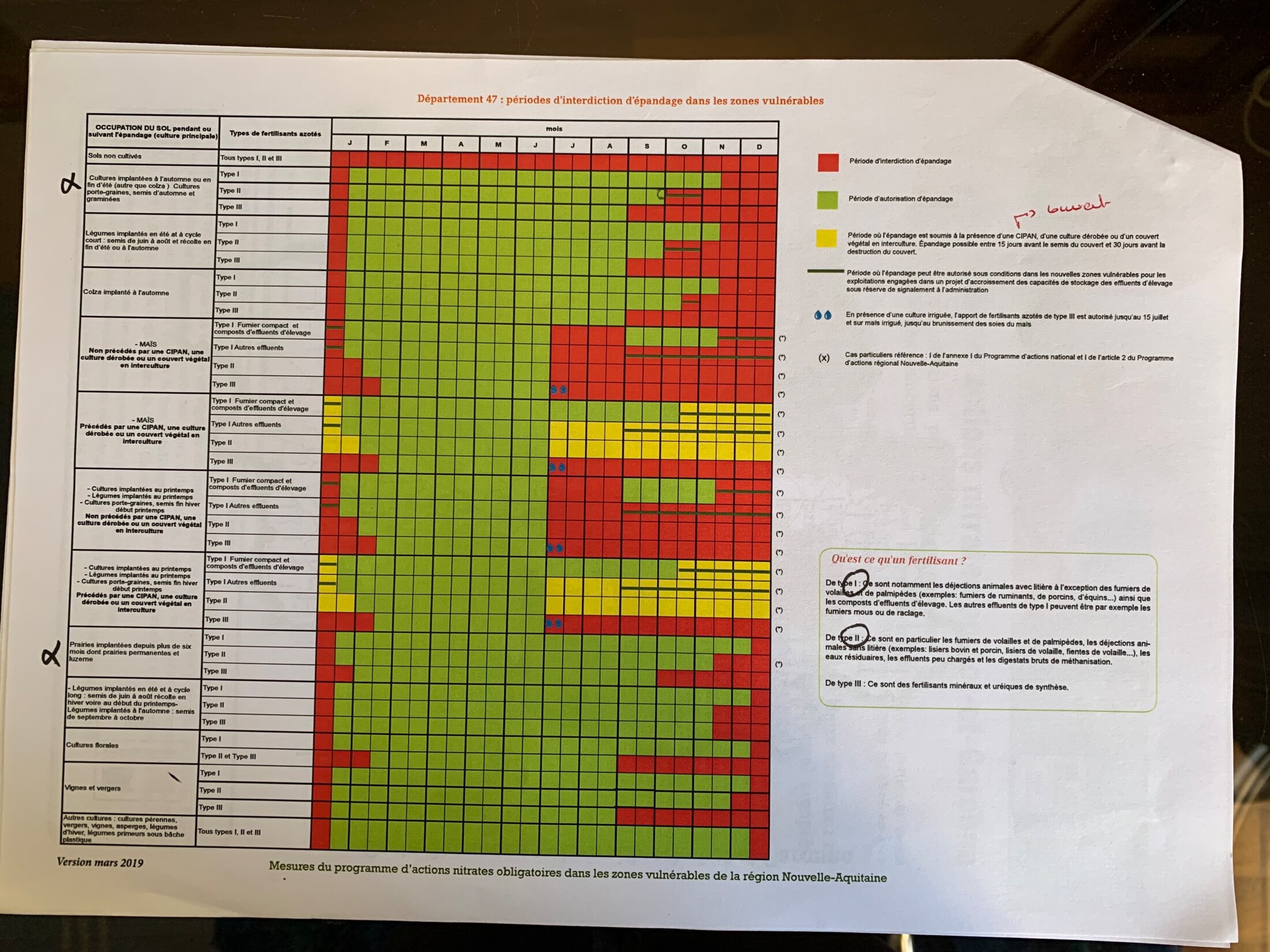

Some 70% of the land in the Lot-et-Garonne département is classified as “vulnerable” in terms of nitrates. On this land muckspreading must take place at precise dates. Karine and Pierre Moinet show a calendar filled with red boxes for when spreading is banned, and green boxes for when it is allowed. The muckspreading periods vary with the type of crop: from July to January or February according to the type of maize grown, from September or November to January according to the different types of rapeseed, and so on.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The muckpreading schedule is also subject to the vagaries of the weather. It is banned when it is raining or when it is too windy. And the ASP cross-checks the dates shown on a farmer's records with data from Météo-France, the meteorological agency. Agnès Chabrillanges of the Chamber of Agriculture, gives a dry laugh. “To spread manure the wind must not be blowing at more than 19 kilometres an hour, when the leaves on the trees are stirring...” she says, citing the rules. Karine and Pierre Moinet are frustrated by such stipulations. “We're not stupid, you simply don't spread when it's windy or raining,” they say.

The rustling of corn silks

Some of the boxes on the calendar have a black line through them to indicate a “period when muckspreading can be authorised in certain conditions in vulnerable areas for those farms which are planning to increase their storage of animal effluent, as long as the authorities are notified”. Some of the red boxes also have two water drops. “Where there are irrigated crops, the use of type III nitrogen fertiliser is allowed until July 15th and on irrigated maize, until the corn silks start to rustle,” state the rules.

Karine and Pierre Moinet are incredulous over such words, as is Agnès Chabrillanges of the Chamber of Agriculture, one of whose jobs it is help farmers respect environmental measures. “That's too technical as far as I'm concerned,” she says. “The authorities use incomprehensible language. We try to translate. In reality it's all done so that the farmers make mistakes.”

And any error spotted during an ASP farm inspection is punished. “The farmers can lose 2% of their entire CAP subsidy,” says Agnès Chabrillanges. Karine and Pierre Moinet say: “Those who lose 50% or 100% of their subsidies don't recover.”

It's all very much like Soviet farming, mixed with liberalism.

Victor Chazalmartin has planted hedges on his land, which also entities him to subsidies. As a result he has to comply with 16 European regulations which oblige him to make numerous declarations. He lists the destinations of these various declarations, unable to recall them all. “The Chamber of Agriculture, the DDT, the Fédération des Chasseurs [hunt federation], the town hall, the département if you're next to a departmental road, the Office National de la Biodiversité … You have to measure the length and width of the hedges. We're lost all common sense. This costs us time and loses us working land.”

He also questions how useful hedges, which are supposed to stop soil being eroded by the rain, really are in his region. “The Lot-et-Garonne is not like the Beauce [editor's note, a region of rolling arable farmland in the north of France]. We have small fields, woods, copses, lots of tree-growing. The soil is kept in place, even on livestock farms it's mostly grass that's grown,” he says.

The biodiversity subsidies also seem to him to be “counterproductive because they are discouraging. You have to declare every single tree on a plot, subtract it from the surface area. If you reach 3% or 7% of the surface area in terms of environmental value – hedges, trees – you have a right to this subsidy,” he says.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

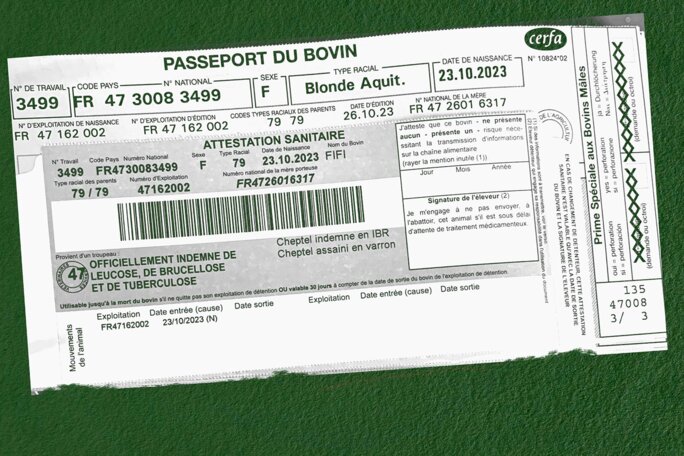

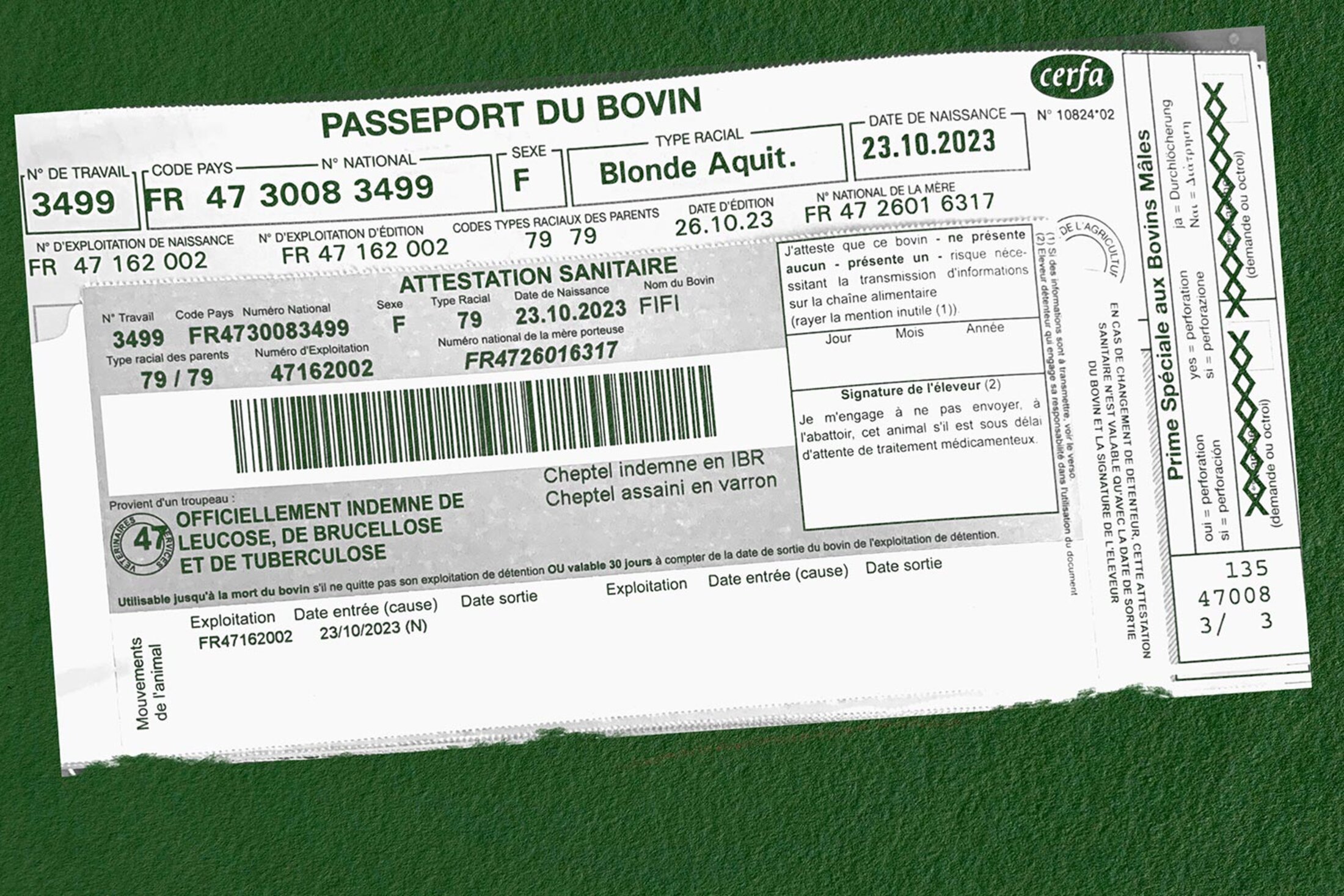

Keeping cattle is subject to the same demands. The animals have to be tagged on both ears. “As soon as you lose one you have to reorder immediately. Because if the cow loses the second one and you have to reorder two, you get an inspection,” explain Karine and Pierre Moinet. The cattle also have their own passports, which show their registration number, their mother's number, and their date of birth.

Livestock farmers also keep a herd book recording all the events that occur: the birth of a calf, the insemination of a cow, a death, vaccinations and screening, any illness and its treatment, the time an animal goes to the abattoir and the time it arrives there, the destination, and the name of the haulier.

“There's no point imposing all these standards on farmers,” says Victor Chazalmartin. “You have to tell them what direction they have to go in and ensure they get a proper income. After the war, when farmers were told they had to increase production to feed France, they did so without following a muckspreading calendar. It's all very much like Soviet farming, mixed with liberalism. But at least the Soviets guaranteed an income for their peasants.”

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter