Mediapart today publishes the results of an investigation which reveals the mismanagement at the highest levels of the French state over the key issue of protective masks. These errors, which have occurred from January right to the current day, amount to a state lie and have led France to an unthinkable situation: a shortage of masks for healthcare workers on the front line in the battle against Covid-19 coronavirus crisis, and for the public in general.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

- At the end of January and start of February the Ministry of Health, though aware of the state's low stocks, only ordered a small number of masks, despite internal warnings. This equipment then took several weeks to arrive.

- After this first fiasco, at the start of March the French state created an inter-ministerial unit dedicated to buying masks. But once again the outcome was catastrophic: during the first three weeks of March this unit only obtained 40 million masks, enough for just one week at current rates of use. In particular the unit missed several opportunities to obtain rapid deliveries of supplies.

- The government hid this shortage for nearly two months and adapted its health advice on wearing masks according to the level of stocks. At the end of February the country's top health official recommended wearing a mask for anyone in contact with a person with the virus. A month later the government's spokesperson said it was pointless.

- Some companies in “non-essential” sectors of the economy continued to use masks for economic reasons. An example is the aircraft manufacturer Airbus who seem to have received favourable treatment. At the same time some nursing staff have continued to work without protective masks because of insufficient supplies.

- The government is now trying to replenish the stocks, accompanied by a completely new strategy in which they are having to prepare for the end of the lockdown “when we know [the public] will need to be massively equipped”, as the junior economy minister Agnès Pannier-Runacher admitted in a meeting of which Mediapart has obtained a recording.

Below Mediapart sets out the different stages of this unfolding tragedy.

*

♦ ACT I (end of January 2020). A lie about a shortage

“The big mistake in the US and Europe, in my opinion, is that people aren’t wearing masks,” George Gao, director-general of the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), told Science magazine on March 27th. The virus is transmitted by droplets and close contact, and droplets play a “very important role” said the Chinese official who was on the front line in the battle against Covid-19. “You’ve got to wear a mask, because when you speak, there are always droplets coming out of your mouth. Many people have asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic infections. If they are wearing face masks, it can prevent droplets that carry the virus from escaping and infecting others,” said Gao.

The problem was that in mid-January, when the epidemic started in China, stocks of masks were almost non-existent in France.

Mediapart understands that at this time there were fewer than 80 million 'surgical' masks in France plus a further 80 million which had been ordered but not delivered, and zero stocks of the more protective 'FFP2' masks.

Surgical masks are the basic masks against projecting the virus, designed for the public and with a period of usefulness limited to four hours. They do not protect those who wear them but stop the wearer from infecting others.

The second type, plus the top of the range FFP3 masks, are protective respirator masks to be used by nursing staff. Only the FFP2 and FFP3 masks protect the wearer. During a pandemic they should be given to all staff who are the most exposed to the virus: hospital nurses and doctors, GPs, firefighters, ambulance staff and so on. Yet France had no stocks of these.

That decision was made not by the current government but its predecessor. In 2013 the then-minister of health, Marisol Touraine, had in fact decided to get rid of the state's strategic stocks and to transfer responsibility for them to employers, whether public or private, who from then on had the task of “establishing mask stocks to protect their staff”.

Rather than being transparent about this shortage – which was not of their doing – and explaining that the few stocks that were available would be reserved for nurses, prime minister Édouard Philippe and his government chose not to inform the French public. And they used false health arguments to hide the inadequate stocks. First the government explained that the masks were useless for the general public, then that they were not effective because French people did not know how to wear them before, belatedly, the government has switched to trying to “massively” equip the public in order to get ready for the end of the current lockdown.

*

♦ ACT II (end of January, early February). A slow and inadequate reaction

By the end of January some in the team around Jérôme Salomon, the country's director general of health and the top public servant on health issues, were already getting worried, Mediapart understands. But politicians did not dare admit to the public that there was a risk of a shortage of masks and preferred to say initially that the masks were useless – until such time as the orders arrived.

On January 24th, a few hours before the confirmation of three European – French – cases of Covid-19, the health minister at the time, Agnès Buzyn, sought to reassure people as she left that day's scheduled meeting of ministers: “The risks of the spread of the virus in the population [editor's note, French population] are very small.”

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The French public took no notice. From mid-January “many people rushed into the chemists, into DIY stores to buy masks, online, everywhere. It quickly emptied stocks,” said the commercial director for the West Mediterranean area for American manufacturer 3M, one of the world leaders in making masks, in a confidential internal meeting. The emptying of supplies was hastened by the fact that “many masks stocked in France went to China or elsewhere”. The commercial shortage was so acute that from the end of January 3M “stopped supplying” French chemists and “prioritised” the hospitals, the commercial director said.

Health minister Agnès Buzyn's comments were also completely out of step with the reality experienced at that very moment by the Ministry of Health's own crisis unit which was studying a plan of action of the different stages of the epidemic. The 25-strong unit, which is made up of staff from the ministry's monitoring centre CORRUSS and its health security monitoring directorate, was worried about the low stocks of masks. “We started to get worried and we got ready for battle to buy them in massive numbers at the end of January,” one member of this crisis unit told Mediapart, on condition of remaining anonymous.

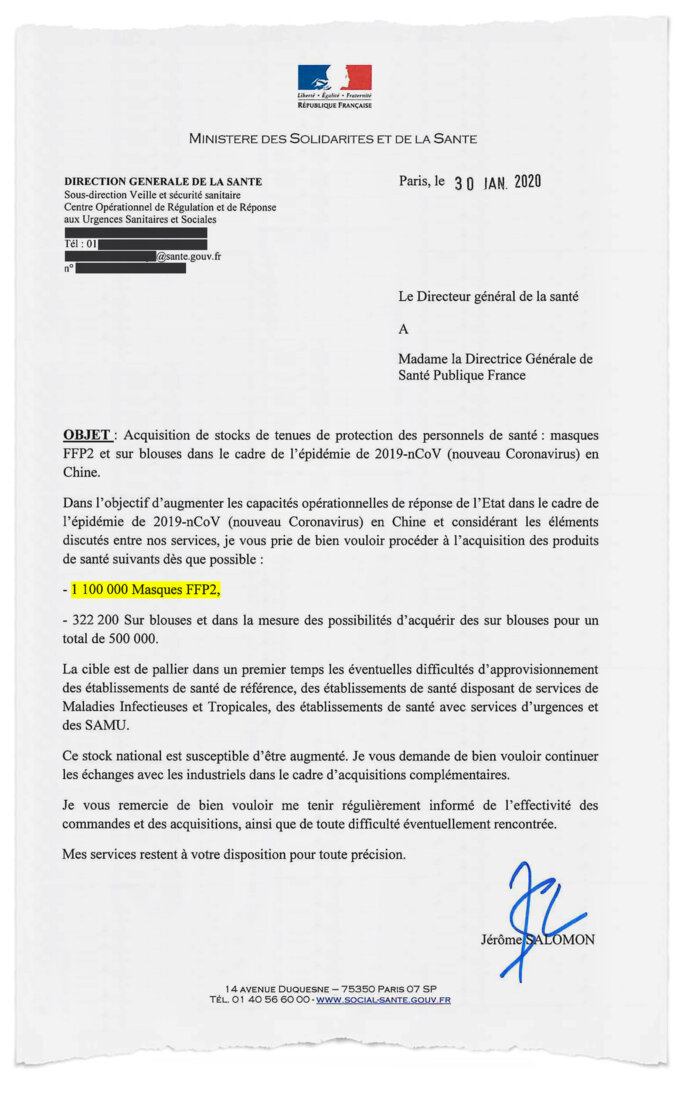

On January 24th the Direction de Générale de la Santé (DGS), the body that oversees health policy in France and which is headed by Jérôme Salomon, asked the public health agency Santé Publique France (SPF), which is under the authority of the ministry, to carry out an inventory of medical supplies. On January 30th the DGS then asked the public health agency to buy “as soon as possible” 1.1 million FFP2 masks only, according to a document seen by Mediapart:

Enlargement : Illustration 3

On February 7th the DGS made a new request for the public health agency. This time it was to buy 28.4 million FFP2 masks via an “accelerated purchase procedure” by contacting just the three main French producers. No new orders were made for surgical masks. Moreover, the DGS ordered supplies of 810,000 surgical masks with short expiry dates (March 31st or August 31st 2020) to be sent to China.

Two weeks after the first DGS purchase request, the results were catastrophic. By February 12th, out of the 28.4 million FFP2 masks asked for, the SPF had received just 500,000 and had ordered another 250,000 which had not yet arrived. As for the planned 160 million surgical masks, there was still a shortfall of 30 million masks which had been ordered but not delivered.

Inside the Ministry of Health concern was growing as officials worried about the problems of supplies and the slowness of Santé Publique France to react. At an internal meeting on February 11th it was acknowledged that the goal of achieving 28.4 million FFP2 masks was in jeopardy. That did not stop the new health minister – by now Olivier Véran had replaced Agnès Buzyn who had become President Emmanuel Macron's preferred candidate to be mayor of Paris in the March local elections – to declare several times on France Inter radio on February 18th that “France is ready” faced with the “risk of a pandemic”.

How can this fiasco be explained? The Ministry of Health insists that it came up against a very competitive market – limited supplies, growing demand across the world, rising prices – in particular against Asian countries who already have their usual supply chains. But the government had clearly committed several errors: making very low-volume orders that were too late and too scattergun – each ministry ordered for itself, reducing the buying power in negotiations. Finally, the executive had used public contract procedures that are ill-suited to an emergency. This includes those operating at European Union level.

'There is no question of shortages' - health chief Jérôme Salomon on February 26th

On February 13th, three days before she quit as health minister to campaign to become Paris mayor, Agnès Buzyn announced at a Covid-19 press conference details of a “European public deal” for a massive supply of masks rather than each country equipping itself separately. Six weeks later and no one mentions it any more.

The European Commission is only now starting to examine proposals, with a view to the material being made available two weeks after any contact is signed. “We're doing our best to accelerate considerably the administrative process for the joint execution of contracts,” a Commission spokesperson told Mediapart on March 30th, without being able to give any indication as to the timing or volume of any order or how it will be divided per country.

“There were perhaps some mistakes,” a member of the French health ministry's crisis unit told Mediapart. “Without doubt the state has not been sufficiently reactive and has been too conventional in its demands. The public contract procedures are very good when it's calm, but completely unsuited when things get stormy and you have to take quick decisions, given that the tender process is three months...”

For this health official the problem stemmed mainly from the decision “not to have strategic stocks of masks”.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

The government also clearly underestimated the speed and virulence of the epidemic. “We were aware from the start that a wave was going to arrive,” the same health source said. “But we didn't think that it would be of such strength, that the virus would be so violent, with patients who can worsen just like that and who require urgent treatment.”

In mid-February the Ministry of Health sounded the alarm with public health agency Santé Publique France, in particular at a technical meeting about the implementation of a supply and distribution plan. They were told to operate at top speed, stop using their usual long public contract processes, to look everywhere and to operate “in warrior mode”.

But the public health agency did not seem to be fully aware of the urgency of the situation. On a broader level its slowness to react is due to the way it works: it was created in 2016 from the merger of three health agencies and “equipped with a five-year plan like in Soviet times” said some sources.

Though it was supposed to be more reactive than the ministry and less subject to its administrative constraints, in fact the SPF machine suffers from the same ponderousness even though it has to act urgently. This has been exacerbated by the merger as its 'intervention' arm, which was run by the former Établissement de Préparation et de Réponse aux Urgences Sanitaires (EPRUS), has been neglected. When questioned by Mediapart, Santé Publique France declined to comment and referred us to the Ministry of Health.

After this alert in mid-February the Secrétariat Général de la Défense et de la Sécurité Nationale (SGDSN), a body run out of the prime minister's office to organise the state's response to the most serious crises, whether health or terrorist related, met with different government ministries. It called on them to rely on the four French industrial producers of FFP2 masks. The minister of health's staff then called in representatives from these businesses and brought together all the state's orders under one single buyer, Santé Publique France. The aim was to carry more clout with suppliers during negotiations.

By the end of February the epidemic had started to affect Italy to a worrying extent and the French government began to panic. On February 25th a crisis inter-ministerial meeting was chaired by Édouard Philippe. According to what the Ministry of Health has told Mediapart, an additional “need” for 175 million FFP2 masks had been identified “on the basis of a three-month epidemic”. The ministry said that on the same day health minister Olivier Véran authorised Santé Publique France to order them.

In public the Ministry of Health has sought to be reassuring. On February 26th the health minister Olivier Véran said that in relation to the “high level masks” - the FFP2s – a “public order had been made” in order to “establish a stock of several tens of millions”. The next day he said the ministry had not just been “reacting” to events but instead had been anticipating them “for weeks”. He insisted: “We are and we will stay ahead of things.” Meanwhile the head of the Direction de Générale de la Santé (DGS), Jérôme Salomon, stated on February 26th: “There is no question of shortages.”

*

♦ ACT III (end of February – start of March). The failure of the command unit

In private, however, the government had decided to change gear. Santé Publique France clearly seemed ill-equipped to control the ordering, collection and distribution of the masks and a more aggressive strategy was put in place. The government created a special Covid-19 inter-ministerial unit called CCIL (for 'Cellule de Coordination Interministérielle de Logistique') which was officially activated on March 4th. It included a team devoted to buying masks who were tasked with boosting supplies by all possible means.

This mask 'sub-unit' mostly included staff from the SGDSN and the Ministry of Health, and was initially headed by Martial Mettendorff, the former deputy director general of Santé Publique France. He was the man who had received the order from the ministry in February to accelerate the buying process. Less than a month later he was replaced at the head of this 'mask unit' by an adjutant general from the army.

The results produced by this inter-ministerial command unit have been very meagre so far. In the three weeks or so from its creation to March 21st, the unit was only able to obtain 40 million masks from all sources (French production, requisitions, donations and imports), according to the Ministry of Health. That represents just a week's work of stock at current rates of use.

Yet on paper the government appeared to be having a big impact. On March 3rd the prime minister issued a decree requisitioning both all the existing stocks of masks on French soil and those which were coming out of factories.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

However, the attempts to requisition stocks of masks held by French institutions and companies has experienced some setbacks. On March 25th the CGT trade union public service federation warned the minister of the interior, Christophe Castaner, that “tens of thousands of masks are still waiting to be collected”. This came to light after the CGT coordinator for firefighters, Sébastien Delavoux, who was seeking to tackle the shortage of masks in the Haute-Savoie département or county in the French Alps, called round union representatives in various public energy companies. “We found tens of thousands of masks after just a few phone calls. In several places the masks had been gathered but no one had come to take them,” he said.

The requisition order has also had some perverse effects. “We were navigating by sight,” said the member of the crisis team cited earlier, who said that “the remedy was without doubt worse than the cure”. He said: “The requisition had not been prepared. After the Tweet by Emmanuel Macron announcing it, the decree had to be produced quickly.”

One key factor that had not been “anticipated” by the government was the fact that the requisition of masks would “drain the traditional supply chains in two weeks, because the professionals who deliver to health establishments and pharmacies in particular have stopped, not knowing what they were allowed to do or whether they were going to be paid,” said the crisis unit source. “We found ourselves in difficulty and that clearly delayed the supply of masks. The Germans had banned exports rather than requisitioning them.”

On March 20th, three weeks after the requisition, the government performed a U-turn and authorised public and private enterprises once again to import masks freely.

But the most disappointing outcome concerns the purchase of masks from abroad. According to an estimate compiled by Mediapart, and subsequently confirmed by the Ministry of Health , the “mask unit” succeeded in importing fewer than 20 million masks between the start of March and March 21st. The ministry stated publicly that these “difficulties” arose from the “world rush for masks” caused by the pandemic which has meant “no country in the world can meet its demands”.

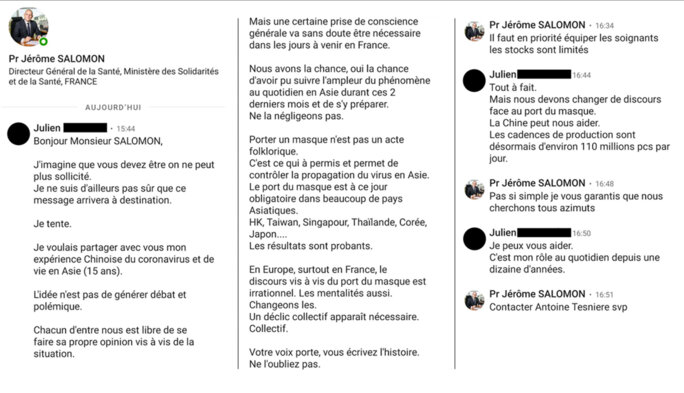

However, some mistakes were made. In fact, Mediapart understands that some serious offers of help were simply ignored. An example was one from Julien, an expert in sourcing industrial produce in China, who has asked to remain anonymous. He lived in China for ten years, has experienced several viral epidemics and has followed the crisis closely through friends in Wuhan, the city where the epidemic began.

Shocked by the French policy of advising people not to wear a mask, Julien contacted the head of the Direction de Générale de la Santé (DGS), Jérôme Salomon, on March 13th. “Wearing a mask is not a bizarre act. It is what has enabled and is enabling the control of the virus's propagation in Asia,” wrote Julien via LinkedIn. “The wearing of a mask is obligatory in many Asian countries … the results are convincing. ...In Europe, especially in France, the discussions over the wearing of a mask are irrational. The mentality too. Let's change them.”

Enlargement : Illustration 6

Julien then suggested helping the French state by mobilising his own network in China. Jérôme Salomon directed him to Antoine Tesnière, the health minister's Covid-19 advisor. Two days later, on March 15th, Julien sent a detailed proposal in which he said he had found factories capable of supplying 6 to 10 million surgical masks a week including 1 million FFP2 masks, which are in very short supply. His email was sent to the head of the “mask unit”, Martial Mettendorff, and the head of the SGDN, Claire Landais.

On March 16th Julien spoke on the phone with Antoine Tesnière's deputy. According to Julien, she told him that the unit had no need of help because it had its own network in China. In an exchange of text messages that Mediapart has seen, Julien's Chinese suppliers said they had not been contacted by the French state.

“I was shocked, because in three days I had found them reliable factories, which had the capacity, the certification and the authorization to export, but they didn't do a thing,” said Julien. “On March 16th one of the suppliers that I had contacted told me they had delivered 70 million masks to Kazakhstan, sending me a video of the operation.”

The Ministry of Health told Mediapart that Julien's offer was rejected because it lacked “reliability”.

A member of the crisis unit acknowledged that the examination of offers from importers was badly handled because of a lack of personnel and because of organisational problems which slowed down the unit's work during the first two weeks. “We were not able to cope with the flow of emails, we lacked organisation. Some people didn't get a reply even though they had serious proposals,” said the source.

The fight for Chinese masks resembled the ‘Wild West’

An offer made by one of these importers, 'Jérôme' (his real name is withheld at his request), was regarded as reliable. He showed Mediapart all of his correspondence with the crisis unit, and, according to email correspondence he provided, the French government asked him to present a detailed proposition for an initial order of 1 million masks produced in China. But after doing so he waited one week before finally receiving a reply that turned down his proposition on the basis that it was too costly.

Jérôme made his offer at the time when France had announced its vast orders for masks, on March 21st (see further below). But the delay in treating his proposition raises questions given both the urgency over the Covid-19 epidemic, and the fierce worldwide competition to obtain masks. “The demand is such that each day that passed, the capacity of my suppliers was falling,” Jérôme told Mediapart. “One of them took an order for 10 million placed by another country.”

It should be noted, however, that the government’s crisis unit was faced with both having to move rapidly, and also the need to closely check supply offers in order to avoid fraud. “The difficulty is that there was also a load of propositions from abroad from companies that didn’t exist, FFP2 masks offered at prices that were crazy in comparison to the usual costs,” said one official source. Another source, from the health ministry, told Mediapart that “fraudulent offers were rife”.

Contacted by Mediapart, a member of the inner staff surrounding health minister Olivier Véran told Mediapart that the inter-ministerial team, made up of experienced “professionals”, had received “numerous offers to purchase or donate [masks] which were studied in order of priority”, and that the team “followed all the necessary precautions to be supplied with equipment of recognised quality, emanating from reliable sources”. The ministry declined to comment on “all the proposed offers” obtained by Mediapart – and which were submitted to it – on the basis that there was no “proof” that those suppliers who presented themselves to Mediapart as being bona fide professionals were in fact genuine.

Enlargement : Illustration 7

It was following a decree published in France on March 20th authorising institutions and private businesses to organise their own supplies of masks that the council of the Vendée and that in the neighbouring Maine-et-Loire département placed orders for a total of 1.2 million masks, which were also destined for the local municipalities in their regions. Many of these were intended for distribution in care homes for the elderly and dependent, and for homecare workers with elderly charges.

Prolaser told Mediapart that it succeeded in obtaining a daily supply from China of 500,000 masks, with the first shipment arriving in France by cargo plane on March 30th. The Vendée département council told Mediapart that that same day it received 30,000 masks which helped plug part of the shortfall while waiting for the state-organised supplies to arrive.

Meanwhile, also available are stocks of masks which do not meet the official “CE” certification of the European Economic Area, but which do respect other international certification criteria which is very similar to the CE norms. On March 16th, the head of a French company that imports items used for advertising and promotional campaigns identified a stock in China of 500,000 surgical masks that have the non-European certification of EFB95. The masks were originally intended for export to Brazil. 'Henri' (not his real name) decided to import the stock and offer it at cost price. “These masks were in compliance [with non-European standards] and of good quality,” he said. “My thought was that it was better to have masks even without the EC stamp than no masks at all.”

Henri contacted the French customs administration to enquire whether it was possible to import them. “They just needed the agreement of the health services, which is understandable,” he said. “But despite several follow-up attempts, we didn’t get any reply from them. We had to free up the stock, which [subsequently] left for other countries.”

Because of the shortages of mask supplies, on March 20th the Spanish authorities temporarily authorised the importation of those without EC certification but which did meet standards for use elsewhere. The French authorities requisitioned, beginning March 13th, stocks of similar non-EC certified masks that were already present in the country, but it wasn’t until March 27th that the importation of such masks was finally authorised.

It thus appears that during the month of March the French government missed several opportunities to import mask supplies, while the global shortage of them saw public and private buyers locked in heated competition to purchase them from Chinese producers. “It’s a war between countries to get served,” said one buyer for a French corporation. “Ambassadors to China are almost at the point of sleeping on the pallets to ensure the security of the batches, and in that game France woke up late.”

Enlargement : Illustration 8

Mediapart has been told by several business sources working in contact with the French authorities that they have warned the government’s “masks unit” that the delays in placing orders will prove a costly mistake, with the market in China for supplies having become, since mid-March, what one called a “jungle”, and another likened to the “Wild West”.

Chinese companies have rushed to meet the money-spinning demand, opening mask production lines as fast as possible. One result has been a fall in quality, and increased difficulty in finding reliable stocks. One example was the discovery in the Netherlands on March 21st of a shipment from China of 1.3 million masks that were defective.

In France, the Paris public health and hospitals authority, the AP-HP, reported in a confidential note that it had received on March 26th a supply of 700,000 masks which did not have EC certification. However, both the Greater Paris (Île-de-France) regional council, which placed the order, and the local branch of the regional public health agency network, the ARS, which checked the batch, insisted they met required standards.

The French health ministry told Mediapart that, beginning on March 11th, it had ordered supplies of 175 million masks, although it did not specify how many of these were bought from manufacturers within France. Meanwhile, the arrival in France of imported masks has been slow; during the first three weeks of March, the inter-ministerial group took possession of less than 20 million masks that were purchased from suppliers abroad.

The health ministry told Mediapart that any evaluation of its “performance” should be set against a “hitherto unseen context” to which every country in need of supplies has been confronted, namely insufficient supply and fierce competition.

*

♦ ACT IV (March). The French economy ministry’s special masks unit for businesses, and the scandal of those that went to Airbus

Speaking before the media on March 28th, French health minister Olivier Véran repeated the message the government has sent out since the beginning of the crisis: “The distribution of masks always prioritises healthcare staff and people who are the most fragile,” he said. But that did not mean that they were reserved exclusively for those two categories, for supplies of masks to companies has continued, albeit reduced. The aim has been to maintain, in as much as is possible, economic activity.

When, on March 3rd, the government issued a decree for the requisitioning of stocks of masks in the country, this did not include all stocks held by companies. According to French news weekly Marianne, one week after the decree was issued, the health ministry had wanted to requisition masks kept by the agri-food industry, which is estimated to use about 1.5 million per week, but was forced to drop the idea under pressure from both businesses in the sector and the agriculture ministry.

Following a period of wavering, the government set out guidelines at the end of March. In a press conference held by phone on March 30th, junior economy minister Agnès Pannier-Runacher said those companies which, before the Covid-19 crisis, were legally required to issue masks to employees for safety reasons could continue to do so during the epidemic.

Enlargement : Illustration 9

Within the French economy and finance ministry’s dedicated administrative department for businesses, the DGE, a special unit was created to help companies to import masks. Quite separate to the inter-ministerial team with responsibility for ensuring mask supplies to the state for subsequent distribution among healthcare workers, the new unit coordinates a network of 150 private buyers spread around the major French business groups.

Pannier-Runacher said the “companies unit” (the “cellule entreprises”) was involved in obtaining supplies of masks from “smaller sized” Chinese producers, while “larger volumes” that are available are passed on in priority to the administration unit in charge of importing supplies for the state. She said that given the mass orders placed by the state and announced on March 21st (see further below) this had allowed for the “locking” of its supply in masks, and it was therefore quite “normal” for her ministry to go about “helping companies, because they allow for providing France with a supplementary resilience”.

Questioned by Mediapart during her March 30th press conference, she appeared evasive concerning the precise number of masks that are used up by the business sector, estimating the volume to be, “Less than a few million per week”. Subsequently questioned again by Mediapart on the exact figure, her ministerial staff declined to reply.

Pannier-Runacher has insisted that the private sector “has not come into competition with the healthcare [sector]”, adding that it would be “erroneous to place the two in opposition to each other”. She also said that the government was “de-stocking” every week sufficient masks for hospitals, and that the only issue in question was that of the “logistics” of their distribution to healthcare staff.

That claim is highly questionable given the shortage of masks denounced by healthcare staff (see further below). Furthermore, the decision to liberalise the purchasing of masks was made just ten days ago and the consumption of supplies by businesses is set to increase. Meanwhile, the use of the masks is far from limited to only essential production, like that of food, or those most exposed to the virus, such as check-out workers in shops. The most striking example of this is that of the giant aerospace group Airbus.

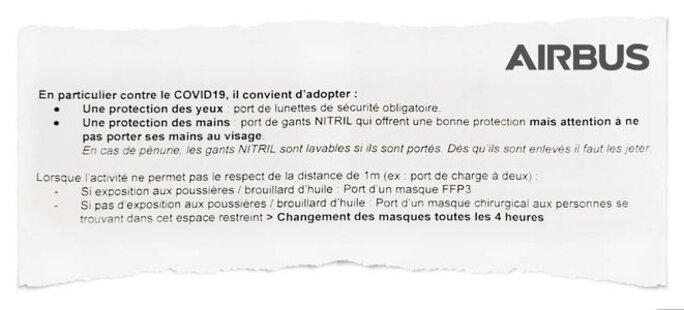

It would be reasonable to conclude that at a time when the Covid-19 epidemic has led to the grounding of around 80% of the world’s civil aviation fleets, there is no urgency for the production of aircraft. But on March 21st, Airbus, whose aircraft branch and assembly lines are based near Toulouse, in south-west France, re-opened its production activity which had been temporarily closed by the virus epidemic. Mediapart understands that the move involved the distribution to staff of a significant number of masks.

On March 20th, the previously-mentioned commercial director responsible for the West Mediterranean area of the French subsidiary of US face mask producer 3M sent out a note to his staff entitled “communication covid ”. The document detailed the priority sectors for mask distribution, and during a conference call with staff the same day he explained that these were based on advice from the French government.

The first priority was for orders placed by healthcare establishments and the pharmaceutical industry. “Priorité 2” was the supply to essential economic sectors like the food industry and energy production, while all other businesses were placed in a third category of priority.

Airbus, however, was included under “Priorité 2”. During the conference call the commercial director explained that the choices were “based on priorities which are defined by the government”, and that “it is not us who decide these priorities”. Regarding Airbus, he told his staff: “I am not going to make a judgement, we’re not here at all to make judgements, but up until now it was among the priorities.” According to another confidential 3M internal document (see immediately below), Airbus was on March 25th finally downgraded from the second priority ranking to third, like the rest of the aircraft manufacturing industry and other “non-priority” businesses, including vehicle manufacturing and the construction industry.

Enlargement : Illustration 10

Neither France’s economy and finance ministry, nor the health ministry, replied to questions submitted to them about the issue.

'We're putting ourselves in danger to make savings'

The Airbus production lines in France re-opened on March 21st after a five-day closure following the announcement of the lockdown on public movement. On March 22nd, Airbus CEO Guillaume Faury announced on Twitter that one of the group’s aircraft, an A330, had landed at Toulouse with 2 million masks from China, of which “the majority will be given to governments”, adding “We are working to support the medical and life-saving teams on the field [sic]”.

But Faury omitted to mention that part of the shipment was also destined for the group’s workforce. Questioned by Mediapart, Airbus confirmed that, “A small part [of the masks shipped] was kept by Airbus in order to ensure the security of personnel who work on our sites”. In short, the group discretely supplied itself with masks from what was presented as a humanitarian mission.

Enlargement : Illustration 11

Furthermore, the same notice to staff said “the wearing of an FFP3 mask” was required “if exposed to dust/oil mist”. FFP3 masks – which are more efficient and more expensive than FFP2 masks – are indeed essential for the safety of employees at certain work stations, but the continued activity and usage of the masks during the Covid-19 virus epidemic is questionable; the FFP2 and FFP3 masks are the only ones to provide proper protection from the virus, and there have been shortages of supplies for some frontline healthcare workers in France. “I am sickened that we use FFP3s when it serves no purpose to assemble planes at the moment,” one Airbus employee told Mediapart. “These masks should be given to the hospitals.”

Enlargement : Illustration 12

For the French government, the issue of the use of the masks by Airbus presents no particular problem. The health ministry told Mediapart that since the March 20th decision to allow private acquisitions of masks, every company “whose activity necessitates the wearing of a surgical mask or of the FFP2/FFP3 type”, even when that activity is not currently essential, are legally entitled to purchase them.

*

♦ ACT V (March). The current mask shortage.

To deal with the “wave” of patients that has engulfed the Paris region, the Bichat hospital in Paris increased the size of its intensive care unit, going from 28 beds to 45 in the space of just a few days last week. But even this is not enough; Mediapart understands that its intensive care unit is already 100% full.

In the hospital's other services, too, nursing staff are on the front line looking after the surge of patients who are “pretty much” in a bad way. Here the shortage of masks is keenly felt.

“Last weekend they gave me three masks, not FFP2s that protect us, but simple surgical ones, for an entire night,” said 'Sarah' – not her real name – who was working with 24 Covid-19 patients, most of whom were in a “critical condition”. This 28-year-old nurse, who usually works in the voluntary sector, volunteered her services to help the existing hospital teams. “I was told I was going to be protected. They showed me videos so I could dress properly in the Covid unit etc.” In reality the nurse got the impression of having been “sent to the front line with no protection.” She said: “It's traumatic, I'm sure I'm already infected.”

The day after her night shift Sarah called the hospital switchboard to say that she would not be returning. In a last bid to reassure her, the hospital gave her the direct line of an infections specialist.

One reason why staffing is so limited is that the reserves of protective masks have reached critical levels. The Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux Paris (AP-HP) hospital group, which employs 100,000 staff over 39 hospitals, had fewer than 2.4 million masks in stock on March 31st, according to reports by its 'masks unit'.

Those stocks largely consist of 2 million FFP2 masks, and its ability to restock them is currently uncertain. The AP-HP group has therefore clamped down on their use in its health establishments, with priority given to staff working in intensive care. Over the space of three days, from March 29th to March 31st, just 20,000 FFP2 masks were distributed each day on average. This is despite the fact that hospitals in the Paris region are facing a record influx of patients.

As a result the instructions issued by the health authorities at the start of the crisis have gone by the wayside. On February 20th, in a note sent to health establishments, the Ministry of Health demanded that any nurse or carer in contact with a “possible” case of Covid-19 should wear a FFP2 mask. But as the ministry has itself explained, the official guidance on using masks has subsequently changed.

To restrict the wearing of FFP2 masks the health authorities are relying on advice from the hospital hygiene society the Société Française d’Hygiène Hospitalière (SF2H) issued on March 4th, in which it said these masks could be reserved for “nursing staff who carry out invasive medical acts or actions in the respiratory domain” on Covid-19 patients. The SF2H itself based its view on a recommendation by the World Health Organisation whose aim was to “rationalise” the use of medical equipment in the face of a worldwide shortage.

There are now major controls on the handing out of surgical masks. Indeed, by Tuesday 31st March the AP-HP group had just 294,000 masks in stock. The one-way flow of these masks shows the seriousness of the situation; over three days the group distributed 829,750 surgical masks but only received 7,500 new ones.

Such is the urgency of the situation that the AP-HP group is now working with Paris-Saclay university and the luxury goods firm Kering – which owns brands such as Gucci and Yves Saint Laurent – to make several hundred extra masks a day using around 60 3D printers.

According to the official figures from its management board, the number of staff at the hospital group who have been infected with the virus since the start of the outbreak has meanwhile risen to 1,200 with a “large proportion of doctors, close to 40%”.

Enlargement : Illustration 13

But this is not just a problem for the Paris region. Nursing staff in many areas of France have been saying for weeks that they no longer have the proper equipment to work safely.

An intensive care nurse at a hospital in Perpignan, in the south of France, where staff have since been infected, told Mediapart on March 19th: “Normally, outside the Covid outbreak, for patients who are in isolation we have to wear a waterproof top gown, gloves, a protective hat and a FFP2 mask, and you throw it all away when you leave the room. Today we are asked to keep our FFP2 masks for its full period (three to four hours). Except that when you are dealing with a patient you get droplets on the mask, and later you're going to make a phone call and come and go in the unit.” She added: “We are really putting ourselves in danger to make savings. We're told: 'There are no masks'.”

This shortage is affecting the entire hospital chain. An example is a psychiatric hospital in the département of Lorraine in the north-east which gave 25% of its stock (10,000 surgical masks out of 40,000) to the main teaching hospital in the north-eastern city of Nancy. This was because “even after the government requisitions” the level of supplies given to the local regional health authority “made it difficult to meet the expressed needs”, management at the teaching hospital explained in an email on March 18th.

The regional health authority concerned, the ARS Grand Est, told Mediapart that the transfer of masks came after a “request” and was not a “requisition”. Its press office said: “It was done in agreement with [the psychiatric hospital] and was based on solidarity between establishments in a period of crisis. No one was prejudiced.”

Nonetheless, the action has had consequences. To free up the equipment the nursing staff at the psychiatric hospital – where according to an internal note several patients have Covid-19 – were asked by the management not to wear masks any more when dealing with patients who did not have virus symptoms. “We've been exposed for close to a fortnight,” complained one nurse, who feared that the virus would spread between patients and staff who displayed no symptoms.

“We've been told about deliveries of masks to the chemist since the start, but where are they? We don't understand,” said doctor Audrey Bidault from the Sarthe département of western central France. For several weeks this geriatrician has been careful with her supply of masks, which she hands out “one by one” to those who need one. She reuses her own surgical masks for “several days” which “is obviously not ideal”, she admitted. Even so, her reserves of masks are disappearing and she is now considering the possibility of recycling her “last FFP2s by decontaminating them at a temperature of 70°C for thirty minutes”.

Despite this Audrey Bidault knows that she is in a privileged position as one of the rare health professionals to have built up her own stock of masks after buying some via the internet at the start of March. This followed her return towards the end of February from a family trip to Japan – where virtually the entire population has masks – which left her convinced that France had to be prepared for the virus's propagation.

As soon as she arrived back on French soil, Dr Bidault contacted the country's top health officials, starting with the director-general of health himself, Jérôme Salomon. “Would it be possible to have the distribution of surgical masks to the public provided at multiple locations?” she asked him on February 24th via LinkedIn. Professor Salomon replied: “Surgical masks are useful in case of an epidemic and they are distributed to people coming back from China and to people in contact with the sick.” Audrey Bidault replied: “In my view that will not prove sufficient. We are not doing enough in terms of prevention.” The top health official responded: “We agree, and are supporting all preventative actions.”

Four days later France moved to 'stage 2' in its epidemic plan. This involves an ongoing attempt to stop the propagation of the virus, bringing in some restrictions, in particular around virus 'cluster' zones.

*

♦ ACT VI (second half of March). Mega orders and mega PR

France was still at 'stage 2' of its epidemic plan when the government decided that the first round of the local elections should still go ahead on Sunday March 15th. The state provided no masks for the people working in the voting stations. The following evening, President Emmanuel Macron announced a two-week lockdown of the population.

At that point Covid-19 had already caused 148 deaths.

In the following days the government carried on briefing its message that wearing masks served no purpose. “French people can't buy masks in the chemist because they're not necessary when you're not ill,” said the official government spokesperson Sibeth Ndiaye on March 19th. The following day she added: “I don't know how to use a mask … these are technical matters.”

This message was then broadcast in different ways across all television channels. “We have to get away from this fantasy about masks,” junior economy minister Agnès Pannier-Runacher told the business channel BFM Business the same day. “Keeping a distance of more than a metre is a lot more effective than a mask. In particular we have cases of contamination from people who wear masks and fiddle with them all day,” she said.

Enlargement : Illustration 14

On March 19th, meanwhile, health minister Olivier Véran finally admitted there was a shortage of masks when he addressed France's second Parliamentary chamber the Senate, and then two days later in a televised speech. He explained, nearly two months late, that the state only had “150 million” surgical masks and no FFP2 masks at all in stock at the end of January.

The health minister also admitted that since the end of February the state has only been able to procure 40 million masks from all sources; French-made ones, donations, requisitioned and imports. There are only up to a million or so FFP2 masks in stock and 80 million surgical masks. This is enough to last two weeks as the country is getting through 40 million a week even though not all nurses are able to have one.

The urgent need for masks after public lockdown is lifted

These figures were however eclipsed by another announcement by the minister on the same day, March 21st, which was that nearly a month after the setting up of the inter-ministerial crisis unit the start had finally been able to order “more than 250 million masks” from Chinese suppliers. This figure continued to be inflated in the media over the following week. By March 27th it had become 600 million, according to Le Monde, and by Saturday March 28th France Info radio put the figure at one billion.

Indeed, Olivier Véran himself referred to the one billion figure during a press conference with prime minister Édouard Philippe on March 28th. However, there was an important qualification. “More than a billion” masks had been ordered in China “for France and abroad, from France and abroad, for the weeks and months to come”, said the minister.

The health ministry told Mediapart that this figure involved orders placed by France but then contradicted itself on the origins of the masks. For though Olivier Véran's office said that these billion masks were going to be “imported” it then said that this figure also included “national production”. If that latter point is indeed the case, it means that the Chinese order is less than a billion.

Whatever the precise detail, the figure of one billion masks ordered from China did the rounds of the media. From a public relations point of view it was job done.

Yet the real issue is not how many masks have been ordered but when they will arrive from China. That is what worries the French government. There are some “uncertainties over the ability to validate the orders made, uncertainty over the reality of their delivery”, junior minister Agnès Pannier-Runacher said on March 27th during a telephone conference with representatives from the textile industry, a recording of which Mediapart has obtained.

The very next day Olivier Véran noted: “I will only be certain that the imports are indeed on our territory ….at the moment that the aircraft supposed to bring the masks land on the tarmac of French airports.”

Given the competition over buying the Chinese masks the first task is to make sure that the masks are indeed made, that they are of the right quality, and above all ensure that one can find aircraft to deliver them. Now that 80% of airline fleets are ground around the world, the price of air freight has exploded and it is very hard to find available cargo planes.

Enlargement : Illustration 15

The government has not given any details on the volume and timetable of deliveries and the health ministry refused to provide them to Mediapart.

Geodis itself has announced 16 additional flights “in the coming weeks” but did not give any details on the volume of masks involved. According to the airport's authorities, quoted by the news agency Agence France-Presse (AFP), these flights are all in April. Working on the basis of around ten million masks per flight that could, if all goes to plan, work out as 40 million or so masks a week. That is just enough to meet the current rate of use, including the current restrictions on use for some nursing staff.

However, the state should be able to count on an extra safety net in terms of supplies thanks to donations from companies such as the bank Crédit Agricole and in particular the LVMH group. The number one luxury goods group in the world has told Mediapart that on March 20th it ordered 40 million masks made in China that it will give to the French government, including 12 million of the important FFP2 masks. Ten million a week are due to arrive during April.

“The big problem is finding aircraft,” said the group. The first batch of 2.5 million masks arrived on March 29th on board an Air France plane chartered by the French logistics and transport group Bolloré. The aircraft was also carrying 3 million additional masks ordered by French companies, including 1 million for the supermarket group Casino for its checkout operators.

*

♦ ACT VII (end of March). A change of 'doctrine'

In an attempt to divert attention away from both the shortage of masks and its slowness in reacting to the situation since the end of January, the French government has stepped up its PR – “communications” – exercises. On March 31st, President Emmanuel Macron visited a mask-making factory belonging to the company Kolmi-Hopen, near the town of Angers in north-west France, when he announced his objective that France should reach a position of “full and total independence” in mask production “between now and the end of the year”.

Macron praised the mobilisation of the existing four mask production plants in France, which in face of the crisis increased weekly production from 3.5 million units to 8 million, adding that the aim was to reach total production of 10 million units per week by “the end of April”, and eventually a weekly 15 million with the help of “new players”.

That in fact represents just one third of the current consumption, which itself is insufficient to meet needs.

The day before Macron’s visit, junior economy minister Agnès Pannier-Runacher had talked up the government’s “initiative” for the textile sector to produce cloth-based masks, which was in fact a project jointly proposed by textile companies. The economy and finance ministry had made contact with a representative of French textile businesses on March 6th to encourage them to turn to mask-making, but several companies had spontaneously begun producing masks in answer to appeals by healthcare workers on social media for help with the shortages.

Such initiatives have continued over recent days, despite the government’s announcements of orders placed with Chinese companies for hundreds of millions of masks. In the Isère département (county) of south-east France, local healthcare workers faced with mask shortages were offered help from ‘1083’, a jean-making company with a factory in Romans, in the nearby Drôme département. “We were called up on March 16th by several doctors in the area who know us,” explained the company’s head and founder Thomas Huriez. “They told us that they had run out of mask supplies and that the teaching hospital in Grenoble had sent them instructions on how to make them themselves.”

Enlargement : Illustration 16

“They didn’t have the time to make the masks, nor necessarily the competence or the sewing machines,” added Huriez. “So they asked us to do it. We began on it on the Monday evening, and we began distributing by Tuesday midday.” He said that since that operation began, 1083 has delivered “thousands” of masks to healthcare professionals, notably those in care homes for the elderly and physically dependent. Other textile companies have been involved in similar projects.

It was not until March 18th that the economy and finance ministry asked the clothing and textile sector to coordinate a national project mobilising companies for mask production. This was via a body called “the strategic committee for the fashion and luxury goods industry” (the “Comité stratégique de filière des industries de la mode et du luxe”), which comprises businesses, staff unions and the public authorities. The aim was to produce two types of masks with, separately, similar characteristics to surgical and FFP2 masks, and which would be only slightly less effective. The state defined the necessary technical standards and designated a laboratory belonging to the French army to test the prototypes. A total of 179 companies answered the call, and 81 of the prototypes that they produced were given the go-ahead for production.

The government hopes that this will soon lead to the production of 500,000 such masks per day, rising to 1 million by the end of April. They are not destined for healthcare staff but instead for private-sector workers and public employees which the state is currently unable to provide with facial protection. They were described by President Macron as, “Those who are exposed in domestic services, to our transporters, to our fire brigade, forces of law and order, [retail] check-out staff, those behind counters, to all the professions who are today exposed who, I know, are often anxious and are waiting for masks”.

Hidden behind this move to bolster mask production in France is a change in policy about the wearing of masks, and which runs contrary to the official line which has previously played down their role of effective protection for the public. This was made clear in the statements of junior economy minister Agnès Pannier-Runacher during a conference call with representatives of the textile sector on March 27th, and which Mediapart has obtained a recording of (see below).

Pannier-Runacher told those taking part that it is now necessary “to increase massively – massively – our autonomy in masks”, and that, “What is at stake for us is finally to prepare the end of confinement [of the public] when we know that it will be necessary to massively equip” the population. Questioned about her comments, a representative of her ministerial office declined to elaborate, insisting that “the doctrine on the use of masks” was “exclusively the preserve of the Ministry of Health”. The latter failed to respond to Mediapart’s questions on the subject.

But Pannier-Runacher’s declarations in the conference call illustrate that the government does not place great faith in its official advice on the priority of refraining from physical contact and the observance of distancing between individuals. Once the public lockdown is lifted, the population will again be exposed, en masse, to the virus and the risk of a return of the epidemic. In that context, the wearing of masks presents an effective protection – and four central European countries (the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Austria and Slovenia) have in recent days made the wearing of masks in public spaces a legal requirement.

At least six legal complaints have been lodged with France’s ‘Cour de justice de la République’, the CJR, a court with the exclusive power of investigating and trying wrongdoing by members of government while in their post. The complaints target Prime Minister Édouard Philippe, former health minister Agnès Buzyn (who stood down in February) and her successor and current health minister Olivier Véran, all of whom are accused of mismanaging the Cofid-19 health crisis, and notably on the issue of the provision of masks.

During his visit to the Kolmi-Hopen mask production plant on March 31st, Emmanuel Macron denounced those he described as the “irresponsible”, who he said were “already into pursuing trials whereas we haven’t won the war”, adding: “The time for [judging] responsibilities will come afterwards, and we will look at all that we might have done better, what we could have done better.”

Macron called for that to be carried out “with a principle of justice, regarding all the past choices, whoever, moreover, are the politicians responsible”. He said that those who “took decisions five or ten years ago” could not have “anticipated what we have just lived through”.

“When one experiences something that has hitherto never happened, one cannot expect people to have forecast it ten years earlier,” he added.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this investigation by Mediapart can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter and Graham Tearse

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------