Until now, the co-called “Pélussin affair” had remained lost in a form of media limbo, lacking a victims' group to make itself heard. But in a report published on Wednesday July 2nd, the post-Bétharram National Assembly inquiry – which examines the abuse scandal at the Notre-Dame-de-Bétharram private Catholic school in south-west France and its wider implications – unexpectedly devotes two pages to it. This forgotten child abuse scandal took place in the mid-1990s at the Saint-Jean secondary school in Pélussin, near Saint-Étienne in south-east France.

As they neared the end of their work, the inquiry's rapporteurs, Paul Vannier, of the radical-left La France Insoumise (LFI) and Violette Spillebout from President Emmanuel Macron's Renaissance party, received a set of previously unseen Ministry of Education files that make particularly embarrassing reading for the minister at the time of the Pélussin affair, François Bayrou.

According to Mediapart's information, the MPs also received a letter dated June 27th from a former teacher in Pélussin who had first raised the alarm about this scandal thirty years ago. “Perhaps I should have asked you to hear from me…”, wrote Élisa Beyssac-Vinay. This modest woman in her sixties has much to say about the systemic violence that took place at this Catholic boarding school in south-east France, and much to say also about the “silence” and “inertia” of the minister at the time, according to what she told Mediapart.

Her letter and the suggestion she should have given evidence arrived just a few days too late for the parliamentarians to be able to call her in. But nonetheless the Pélussin affair is back. And for the current prime minister, that represents a disaster.

For according to Mediapart's investigation, this case could sink François Bayrou’s defence. In February, after meeting the victims of Bétharram, he claimed he was discovering a whole “continent” of abuse claims about which he “knew nothing”. Élisa Beyssac-Vinay told Mediapart of her astonishment at hearing that. While education minister from 1993 to 1997 he was in fact “living in” this “hidden continent”, she said.

Back then this art teacher, alongside her history and geography colleague Marie-Dominique Chavas, “inundated” the government with letters warning that there were “children in danger” at this strict boarding school run by the Marist Brothers religious community.

Documents seen by Mediapart show the teachers received replies from the then prime minister (Alain Juppé) and from the office of the justice minister (then Jacques Toubon). But from François Bayrou, not a word. “You couldn’t get more silent!” said Élisa, still angry today about it.

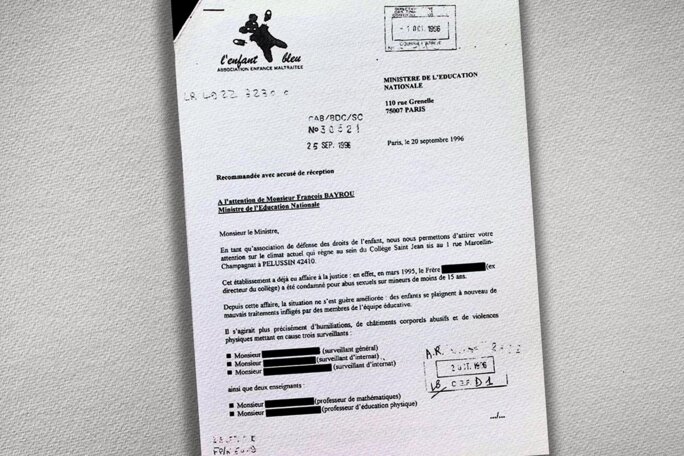

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Mediapart has revisited events of the winter of 1995. At Pélussin, the two teachers were breaking the silence at Saint-Jean just as the Bétharram whistleblower Françoise Gullung, on the other side of the country, was herself coming up against François Bayrou’s wall of silence.

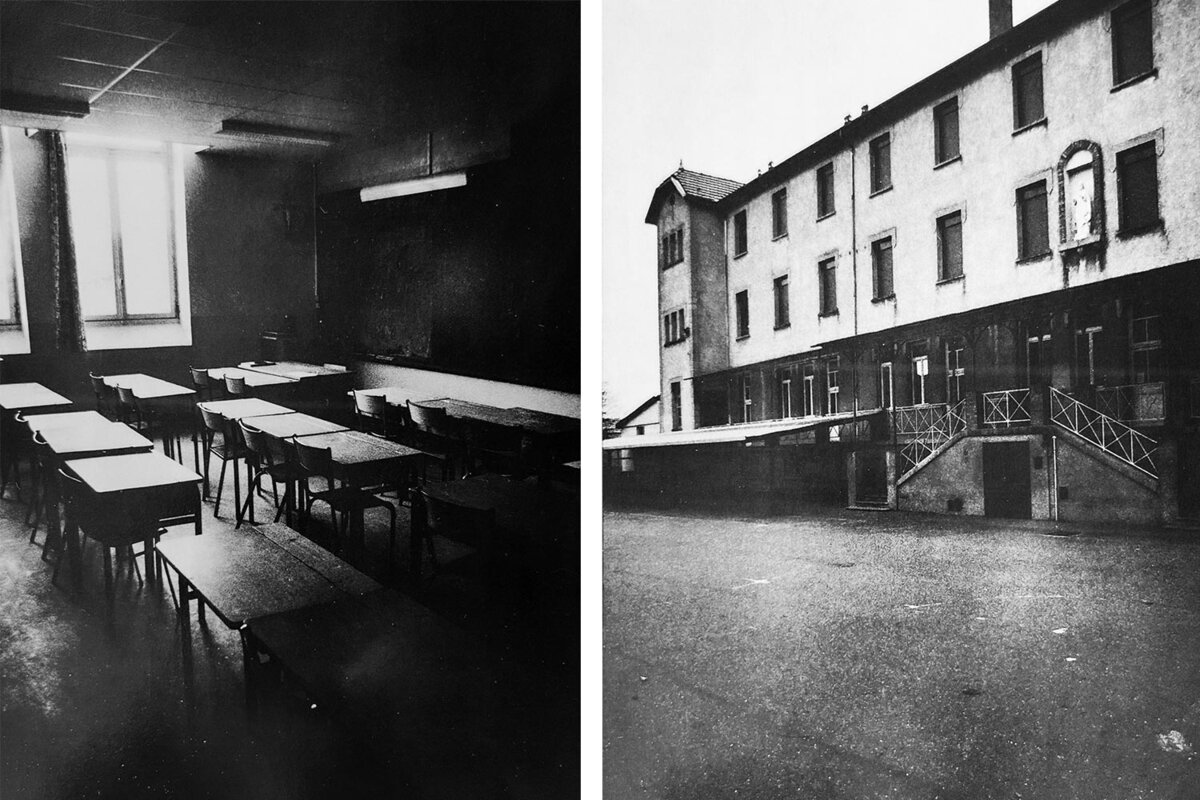

The parallels between the two cases are striking: at Pélussin, too, the head of the school was a sexual abuser, with victims numbering in the dozens; at Pélussin, too, pupils boarding at the school spoke of physical violence and systematic humiliation passed off as “education”, including a pupil suffering a burst eardrum; at Pélussin, too, outraged teachers were ostracised then removed; and even the emergency helpline for abused children was deliberately hidden here as well.

“When I heard about Bétharram [editor's note in February 2025], it reopened Pandora’s Box,” recalls one former pupil at the Marist establishment.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

In truth, at the beginning Beyssac-Vinay and Chavas did not feel the need to turn to education minister François Bayrou. Their first concern and their first act of bravery, in March 1995, was to report their headteacher, Brother Jean Vernet, to the public prosecutor. Over the February holiday that year, Chavas had been phoned by the school cook, who had been confided in by a supervisor: a boy said Vernet had inserted plastic into his anus.

When classes resumed, the teacher arranged a session on mistreatment, to test the water. Or rather, to listen. What followed was a torrent of confidential accounts. “We just opened the floodgates,” recalls Marie-Dominique Chavas. After phoning the regional education authority, the two friends felt nothing would move quickly enough. So they went straight to the prosecutor in nearby Saint-Étienne.

Within days, dozens of children were interviewed by gendarmes. It emerged that headteacher Jean Vernet, who ran the school’s infirmary himself with no medical training, had been abusing children for years under the guise of “examinations” and medical care.

Quickly remanded into custody, the 52-year-old Marist Brother, who continued to deny the allegations, was later convicted of sexual assaults, notably masturbation, on around thirty boys and girls, most under 15. “He slid his hand under my tights. He was breathing fast, drooling,” one pupil said. After an appeal Vernet's sentence was 30 months in prison, twelve of them suspended, with a lifetime ban on “holding a teaching post”.

“But he had a lot of backing from the Marists – it was a state within a state,” one angry former parent told Mediapart. She ended up removing her children from Saint-Jean. Only six families joined the criminal case as civil litigants, despite there being around thirty victims. After Vernet was released, the Marists found him another role, apparently first as a caretaker.

Mediapart tracked down Jean Vernet to the religious community's care home. Now 82, he refused to speak about what happened. “It’s nobody’s business,” he said on the phone. Vernet expressed neither remorse nor regret, simply stating that he “respects the decisions of the courts”. Then he hung up.

June 1996 letter to Bayrou unanswered

At the time, pupils’ testimonies also implicated several other adults at Saint-Jean in physical and verbal violence, some of it of a racist nature. But legal proceedings stalled on these allegations as early as 1995, and the two whistleblowers soon felt they were coming up against a brick wall, both at the diocesan Catholic education office and within the state education system itself.

What made it even worse was that their daily lives at school, surrounded by hostile teaching staff, had become intolerable. So in June 1996, just before the summer break, they again reported the matter to the prosecutor. The head of the regional education authority in Lyon decided to do the same a month later.

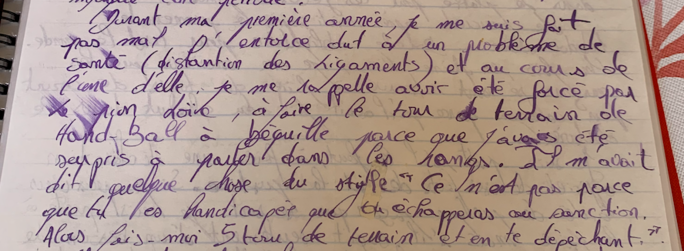

Enlargement : Illustration 3

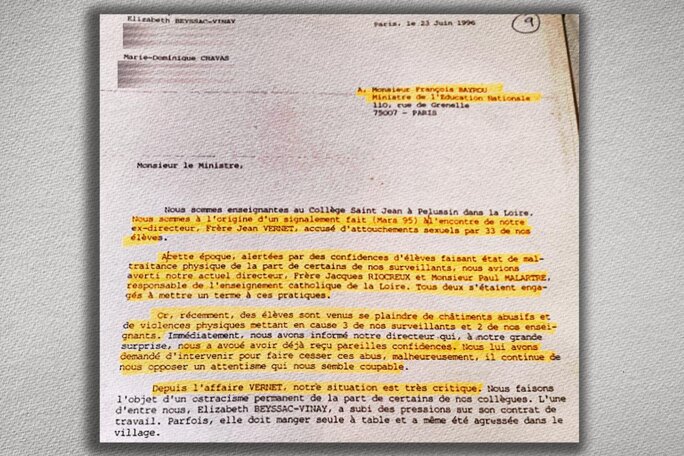

According to a document obtained by Mediapart, on June 23rd 1996 the two teachers also wrote directly to education minister François Bayrou. “Recently, pupils have come to complain of abusive punishments and physical violence involving three of our supervisors and two of our teachers,” they wrote. “We immediately informed our [new] headteacher […]. Unfortunately, he continues to display a passivity that we find shameful. […] Children are in danger, we're being threatened, we can't go on like this.”

They received no reply, either from the minister or his office.

Four hundred miles away in Bétharram that same June, a supervisor was convicted for bursting the eardrum of 14-year-old Marc. Again, there was no visible reaction from Bayrou. A letter seen by Mediapart shows that Marc’s parents and the Pélussin art teacher were in contact at that time. But the minister still failed to see a pattern at Catholic boarding schools.

Yet at Saint-Jean, violence was part of the educational programme. Already, back in 1992, Vernet’s predecessor had been convicted for kicking a girl who was stuck between a wall and her bed.

This time, among the five adults named by pupils was a maths teacher, Mr G. (now dead). During the gendarmes’ investigation he admitted to delivering one slap but denied making a boy run with a sprain or humiliating a black child, even though that incident is still vividly remembered: “He used his head to wipe the board,” recalls 'Élodie', not her real name, a former classmate contacted by Mediapart.

François, meanwhile, definitely remembers seeing “Mr G. lose it and deliver a slap” in class. A graphic artist from Marseille who worked on Notre-Dame cathedral's new lighting, he told Mediapart: “The mark stayed a long time; his mitts were like bricks.”

When asked by Mediapart, the second teacher involved in these allegations, Mr J., a PE instructor, admitted: “It wasn’t rare to give a slap or a kick in the backside when a pupil annoyed us. But that was another era.” He stayed at Saint-Jean until retiring in 2018, and added: “That doesn’t make it right. One realised that later.”

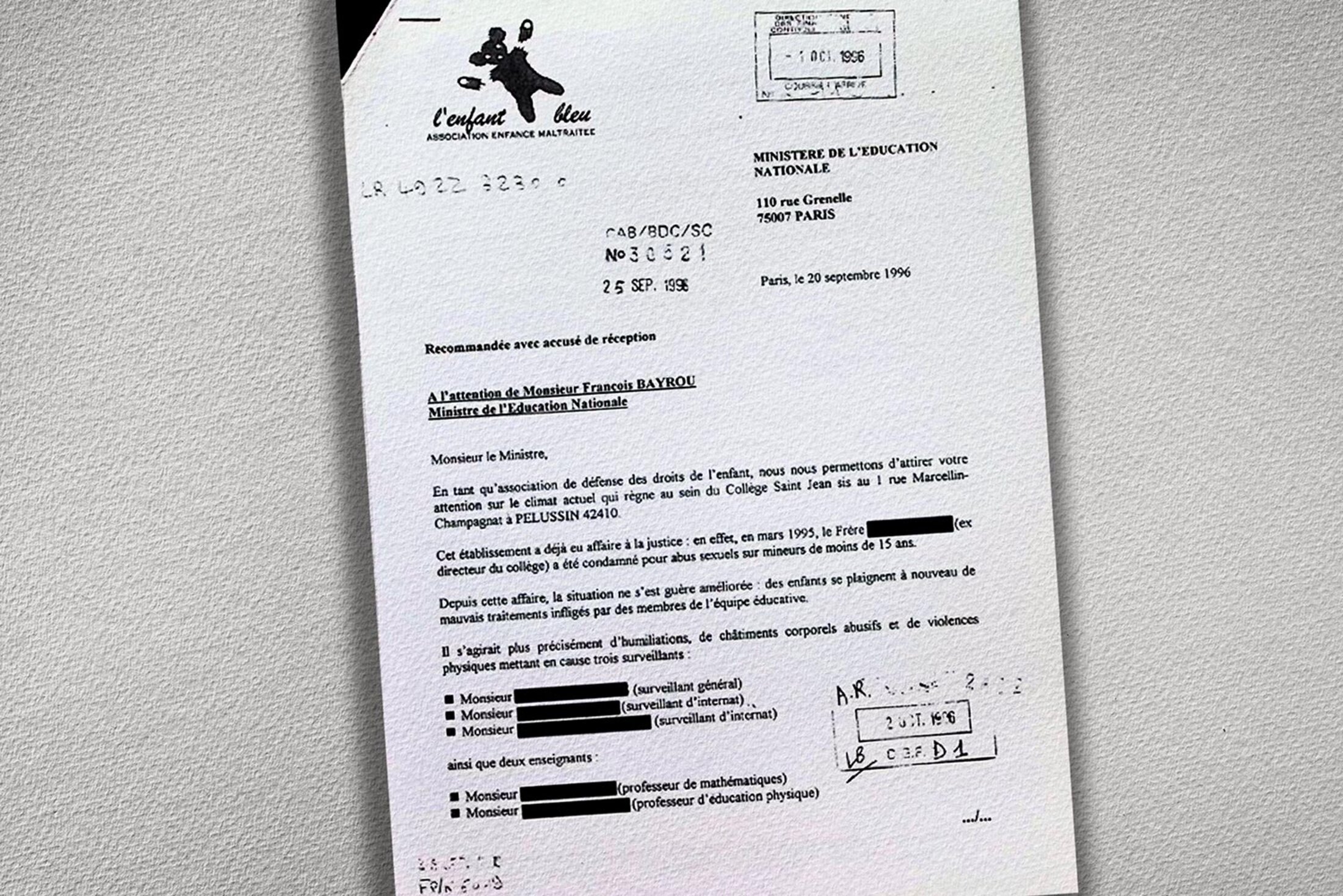

Enlargement : Illustration 4

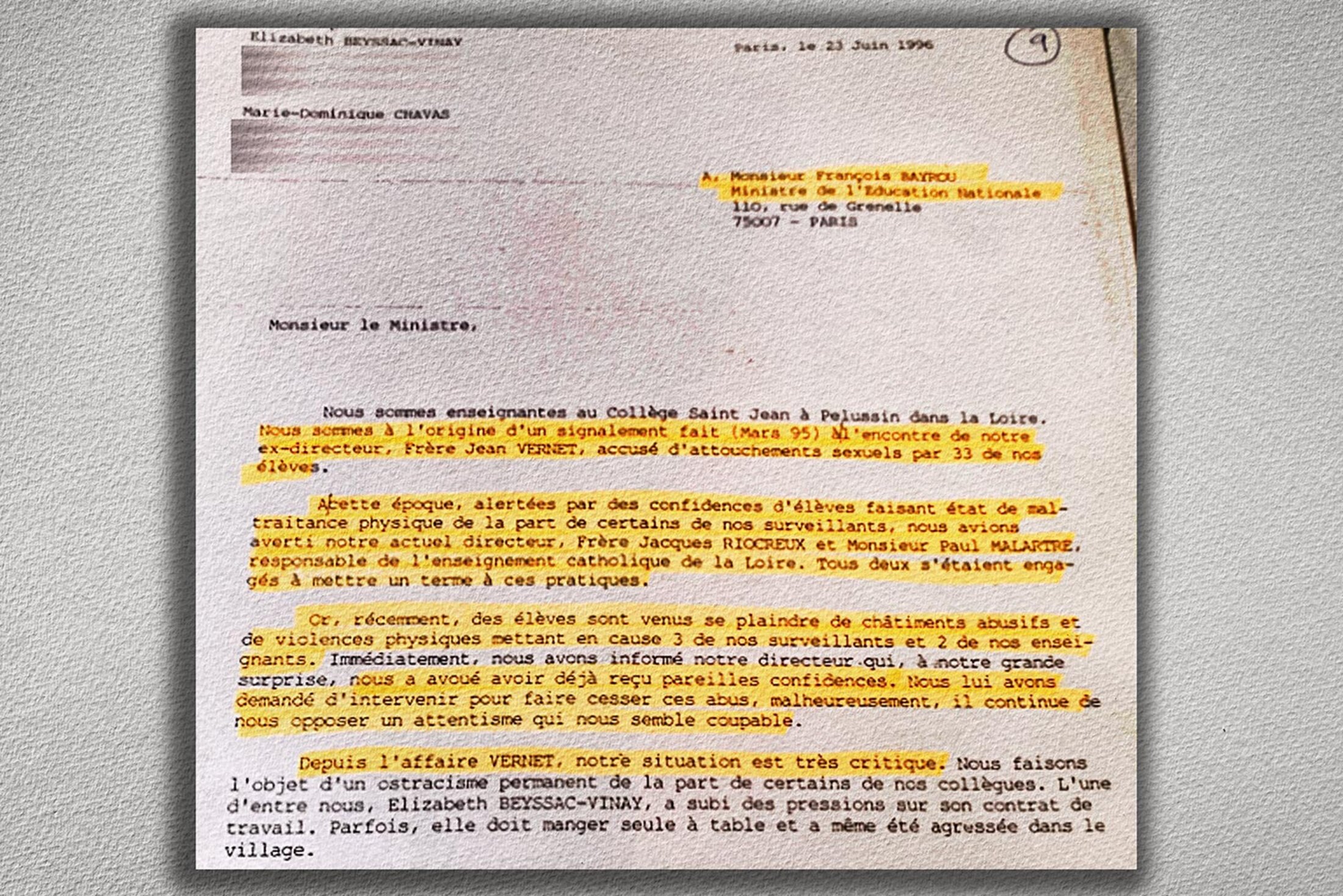

Pupils also gave gendarmes the names of three supervisors in the boarding section, where slaps, push-ups and night runs around the courtyard were routine. One of the supervisors, 'Wilfried', not his real name, allegedly burst a pupil’s eardrum but later claimed it was an accident. Thirty years on, he remembers “nothing at all” about it. “It had become a witch-hunt, everyone was being accused of violence,” he said, dismissing the claims.

His former colleague 'Nicolas', also not his real name, still defends him, if somewhat clumsily. “I believe that story about the [pupil's] eardrum bursting on its own,” he told Mediapart. As for himself, the former supervisor admitted he had “regrets”. “Yes, I did slap and spank,” he said. “But were we cruel? No,” he insisted, recalling he was just 25 at the time. In any case, he added, “there’s a shared responsibility”.

No adult suspended despite allegations

By September 1996 the judicial proceedings had stalled. And when the school returned for the new academic year, not one of the adults named by the pupils over the past 18 months had been suspended, nor were any of them the object of an internal inquiry. Yes as Élisa Beyssac-Vinay notes bitterly, her own contract was not renewed.

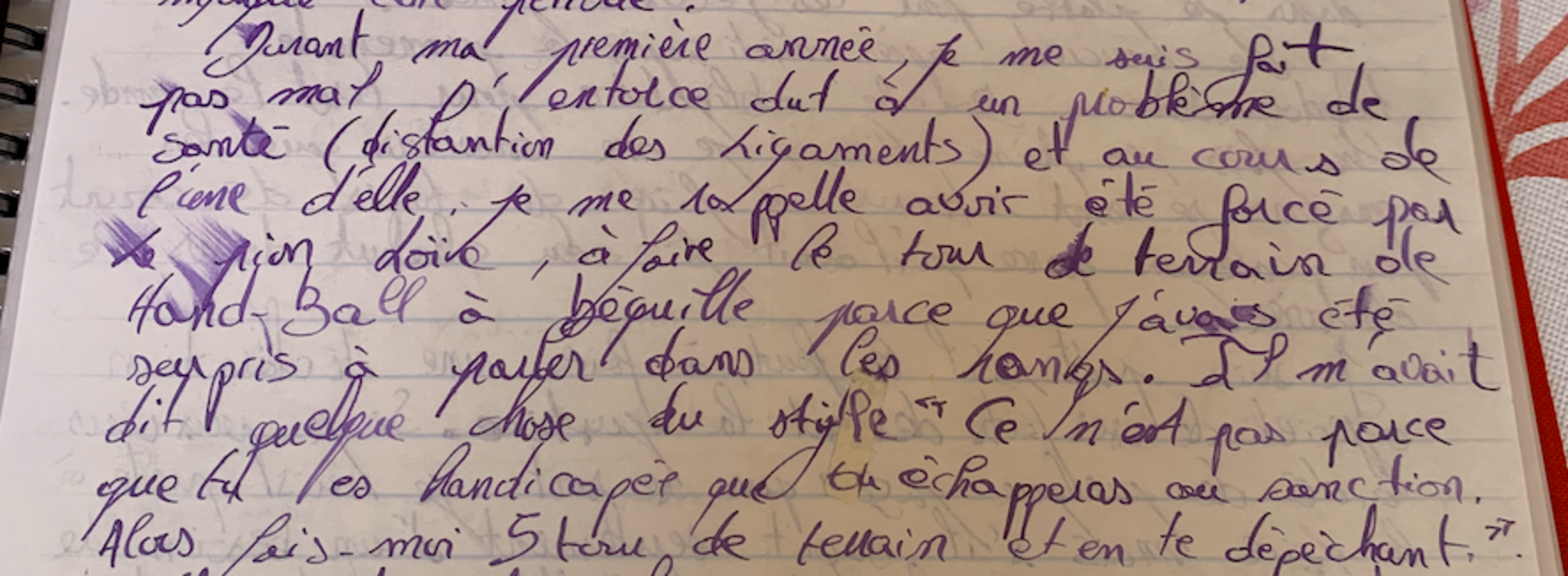

Enlargement : Illustration 5

The anti-child abuse group L’Enfant bleu Enfance maltraitée had now become involved. It wrote to François Bayrou and received a reply from a senior official at the ministry (signed “on behalf of the minister”). Yet the whistleblowers who had stopped a paedophile still received no acknowledgement.

So, in January 1997, the two friends wrote to the French president, Jacques Chirac. “What is the Ministry of Education doing to protect these young people? […] Why is the institution waiting to suspend, while a preliminary inquiry is held, adults who are said to be violent? Can a minister who claims to care about violence in schools be happy with a response of silence?”

The letter hit home. Within days, the head of the president's correspondence passed it on to François Bayrou, referring to “serious allegations”, and asked the minister to “inform [him] of the action taken on this matter”.

François Bayrou’s chief of staff, Nicolas Pernot – who now serves the prime minister in the same capacity - took up the case. “When judicial proceedings are under way […] disciplinary measures can only follow a criminal ruling,” he told the Élysée. In any case, no sanction was handed out. Yet there appeared to be nothing stopping the precautionary suspension of teachers who were paid by the regional education authority.

In order to respond to the Elysée, Nicolas Pernot had clearly got in touch with the head of the education authority in Lyon, who reminded him that allegations of physical violence had been passed on to the public prosecutor (a month after the teachers raised them), and stated that “an audit of the adults was under way” and that a room where children's concerns could be heard had been “set up”.

In the eyes of the whistleblowers this was little more than a bad joke. The “listening unit”, for example, was entrusted to Wilfried, one of the very supervisors accused of abuse. This was the same Wilfried who, according to the earlier judicial investigation into headteacher Vernet's sexual assaults, had kept to himself revelations from several victims that had been made a full year before the scandal came to light. As for the audit, it was said to be an initiative carried out by the Catholic education authority.

Most crucially of all, two years after the first report from Saint-Jean was sent to prosecutors, François Bayrou’s chief of staff was still not talking about holding a full and proper inspection of the school.

A regional education inspector was indeed sent to the school by the authority in early 1997, but only under the pressure of an impending investigation by the Antenne 2 television programme 'Envoyé spécial', which was eventually broadcast in March of that year. At Pélussin, this prompted a rally of 600 people - in support of the five adults under suspicion.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

According to several accounts, the judicial inquiry into those individuals was eventually closed without further action in the summer of 1997. When approached, Saint-Étienne public prosecutor’s office did not respond to Mediapart's questions. Nor did the current prime minister, despite repeated requests.

In April 1997 Jacques Chirac dissolved the National Assembly, and François Bayrou left the Ministry of Education that June, just as the media were revealing cases of child sex abuse in French schools, in a country still reeling from the scandal involving serial child abuser, rapist and murderer Marc Dutroux in neighbouring Belgium.

What was the minister's meagre legacy on this issue? An initial circular on school violence in May 1996, mainly targeting delinquent minors; and a second, issued just before his departure, focusing on the “prevention of mistreatment”. This was so timid that it avoided the words rape, sexual assault, and certainly incest, and instead went on at length about “training” and “work placements”.

We’ve been fighting for more than two years now to have the children’s voices heard.

To the end, and despite the cases at Bétharram and Pélussin, during interviews at the time the minister continued to prioritise “caution”, invoking the presumption of innocence “because words can kill, they are deadly weapons”.

With Ségolène Royal’s arrival at the Ministry of Education after the 1997 elections, the whistleblowers from Pélussin once again took up their pens, denouncing the “inertia” of various bodies, including the ministry under François Bayrou. “We’ve been fighting for over two years now to have the children’s voices heard,” they wrote. They went on to cite cases in other parts of France where there were allegations too, highlighting the “growing number of current failings […] Joigny, Bétharram, Bergerac, Meudon, Narbonne, Marly-le-Roy, Cosne-sur-Loire, Bailly… a list that grows longer by the day”.

At least this time they received a reply from Ségolène Royal’s office. And the Socialist minister did change the tone, if not the ministry's approach, by signing a new circular that, for the first time, used the word “paedophilia”. “The voice of the child, silenced for too long, must be heard,” she declared, citing the statistics. “One child in ten” was subjected to “sexual violence” which in “10% of cases” was inflicted by someone in a position of authority, “such as a teacher”, the new minister said.

Soon afterwards, a parliamentary inquiry into children’s rights and violence was launched at the National Assembly, chaired by former prime minister and future foreign affairs minister Laurent Fabius. It did not even bother to take evidence from François Bayrou. Thirty years on, the 'successor' to that inquiry paid tribute in its final report on Wednesday to the “great perspicuity” of the two Pélussin whistleblowers, who still await from François Bayrou if not a conversion to their cause, then at least a “mea culpa”.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this text can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter