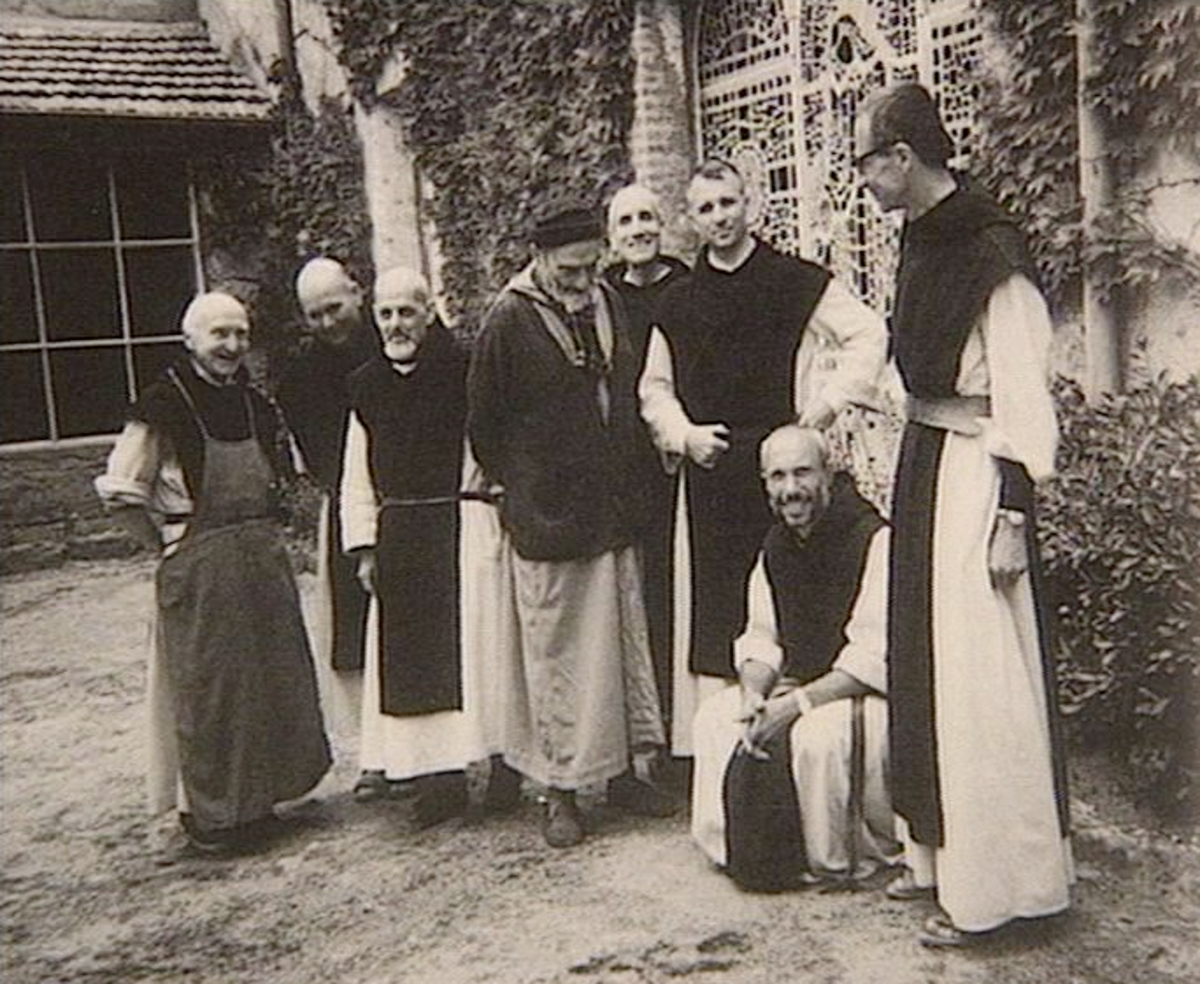

In March 1996, seven French Cisterian Trappist monks1 were kidnapped from their monastery in Tibhirine, Algeria. Their heads were found two months later, on a roadside in the same region, close to the town of Médéa, some hanging from trees in plastic bags. Their murders remain a mystery, despite initial official claims that Islamic extremists were responsible. An ongoing French judicial investigation is exploring the theory that they were mistakenly murdered by Algerian army helicopter gunships, during an attack on a desert camp of suspected Islamic extremists, and their bodies mutilated as part of an appalling cover-up.

Mediapart's report on the astonishing testimony of a French army general suggesting that both the Algerian and French authorities had disguised the blunder was presented in the first of this two-part report. Here, we reveal how French intelligence reports at the time indicated that the Algerian authorities were "slow" in dealing with the hostage taking and displayed a certain "tolerance" towards the Islamic extremist believed to be behind the kidnapping.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Uncovering the ambivalent role played by the Algerian secret services is central to the investigation led by Paris-based magistrate Marc Trévidic. The monks were kidnapped at the height of the conflict between the Algerian state and the Armed Islamic Group (GIA)2, and it was long held previously that the GIA was responsible for the killings.

Several reports of the French counter-espionage services, declassified at the request of Judge Trévidic, indicate that blame for the massacre may not lie with the GIA alone. Mediapart has consulted the documents, composed of three 'confidential defence' reports written by General Philippe Rondot, who was at the time assigned to the Direction de la surveillance du territoire (DST, now called the DCRI),3 the French secret service responsible for counter-espionage and internal security. As such, the general was on the front line during the kidnapping and the ensuing assassination of the Tibhirine Monks.

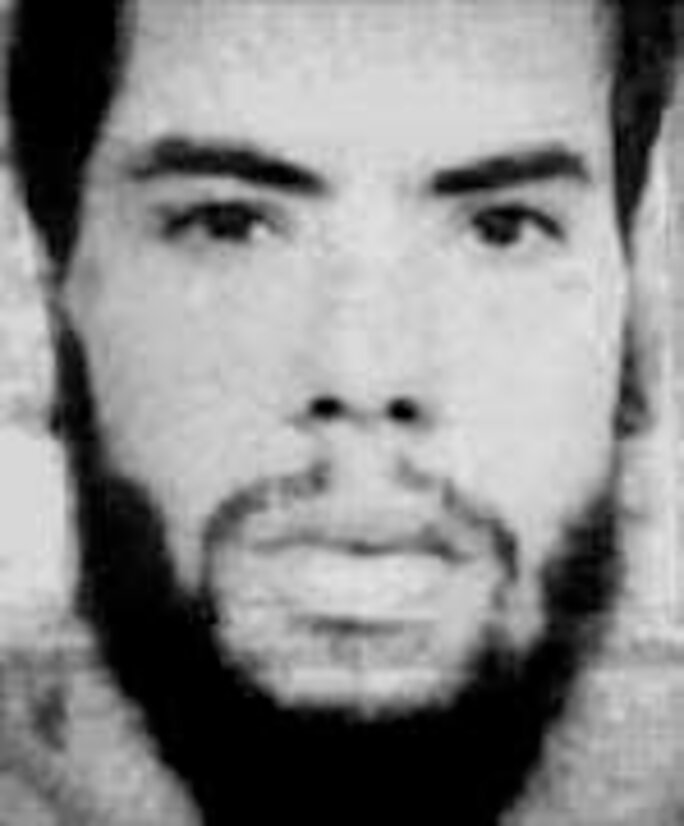

Now retired, General Rondot was heard as a witness on Monday September 27th, 2010, by Judge Trévidic. He was summoned to explain reports he made at the time of the events and which he himself qualified as "bitter musings". In these, he noted the "visibly slow progress" of the Algerian secret services in the management of the affair and their "relative tolerance" towards one of the main leaders of the GIA, Djamel Zitouni, to whom the taking and killing of the monks is officially attributed.

The seven monks were kidnapped from the Trappist monastary at Tibhirine, located 90 kilometres south of Algiers, in the Medea region, during the night of March 26th to 27th 1996. Their heads were found several weeks later, at the end of May, on the side of a road. Their bodies were never found.

Nearly 15 years after the events, no legally-proven truth has emerged from the thick fog surrounding the causes of the massacre. The theory that Islamic rebels are responsible is supported by Algiers and was upheld for years by the first French anti-terrorism magistrate to handle the case, Jean-Louis Bruguière. But this view is seriously flawed, for at least two reasons.

Firstly because, in July 2009, the former military attaché to the French Embassy in Algiers, General François Buchwalter, told investigating magistrates that he had information revealing that, after they were kidnapped, the monks were the unintended victims of an attack on a desert camp by the Algerian army. He was asked by French diplomats to keep his revelations to himself, he further stated.

The second reason is that many clues tend to show that two of the principal terrorists held responsible for the monks disappearance, Djamel Zitouni, a GIA Emir, and his deputy, Abderrazak El-Para, maintained ambiguous relations with the Algerian authorities. At best, the government showed them a degree of laissez-faire, at worse they were agents of the military apparatus, infiltrated into the heart of the GIA in order to manipulate it, no matter what the cost.

-------------------------

1: Dom Christian de Chergé, Prior of the community, 59 (years old). Brother Luc Dochier, 82. Brother Bruno Lemarchand, 66. Father Célestin Ringeard, 62. Brother Paul Favre-Miville, 57. Brother Michel Fleury, 52. Father Christophe Lebreton, 45.

2: The FIS Islamic Salvation Front won the first round of Algerias legislative elections in Dec 1991. The army stepped in to prevent it winning the second ballot and the FIS was dissolved in January 1992. The GIA, Armed Islamic Group, arose at the time to support the FIS. Ten years of civil unrest ensued.

3: The DST merged with the 'Direction central des renseignements généreaux' in 2008 to become the 'Direction central du renseignement intérieur'.

'We can't keep playing this waiting game'

A reading of General Rondot's declassified reports received by Judge Trévidic earlier this year raises serious questions over the behaviour of the Algerian security forces during the Tibhirine events.

Titled 'Operation Tibhirine', the first of these reports is dated April 8th, 1996. It consists of the spymaster's mission report of a trip to Algiers on April 5th to 7th, several days after the monks' disappearance was announced. The document, like the others, is addressed to prefect Philippe Parant, then head of the DST.

General Rondot quickly realised that for the Algerian secret services, with whom he had constant relations, "the priority given to the survival of the monks hampers the force of the search, hence the visibly slow progress in collecting and exploiting information".

Working with Philippe Rondot was the head of the DCE, the Algerian counter-espionage upon which France's DST was at the time especially dependent for information. Too dependent, perhaps. In his first report, the French intelligence officer observed that "although the DCE's cooperation appears to be real as long as one plays by Algiers rules, it must be noted that they remain our only operational source in the field." The report concluded, somewhat pessimistically: "We must remain cautious in our analysis and wary of the product delivered by the DCE, while preparing for the worse."

A month later, on May 10th, 1996, General Rondot produced a second report. The tone is drier and, at times, sharper. The title speaks for itself: '(Bitter) Musings on the handling of the Tibhirine monks affair and proposals (despite it all) for action'.

The monks had not yet been found and anxiety was rising. "We have been waiting since April 30th " he complained. "Meeting after meeting, we have been content to bounce around hypotheses but without defining, in a well-judged and precise manner, what approach we should adopt," he added.

"We can't keep playing this waiting game," he said, complaining again of the DSTs "dependence" on the "Algerian services" whom, he said, "no doubt have other priorities [political and internal security] that differ from ours regarding the survival and the liberation of the monks." The general takes his argument even further: "They can be, in fact, tempted to brutally solve what they consider to be a side story1 (as it's been called) which is impeding normalisation of Franco-Algerian relations (of which the GIA is well aware)."

-------------------------

1: "Fait divers" in the original French.

French intelligence wants Zitouni 'eliminated'

General Rondot's language is unambiguous: "General Smain Lamari told me from the beginning that it would be long, difficult and dangerous. Such is the case," the general said in this second report. He mentioned his unease due to the equivocal attitude of his principal contact in Algerian counter-espionage. "We will not forget either that, among the number of prisoners to be freed, figures Abdelhak Layada, imprisoned in Algeria and it appears unlikely that the government is ready to give in with this case," he wrote. "But the comments made both by General Smain Lamari and the Islamists on this subject are ambiguous," he added.

For Philippe Rondot, the only outlet possible is to make direct contact with the GIA "to find out what's really at stake in this hostage-taking", which implied a lack of clarity and information from Algerian officials. "I'm willing to take the risk," he concluded.

His third and last report, dated May 27th 1996, is a blatant admission of failure; the monks were officially dead but their bodies were yet to be found.

Once again, the general allowed his bitterness towards the Algerian secret services to seep through. Cooperation between the DST and the DCE has been continuous, even if it was too often necessary to badger our Algerian contacts," he noted. "On the other hand, one couldn't claim that the help of the Algerian services was a deciding factor since our seven monks lost their lives. The forces of law and order were defensive rather than offensive in this situation."

"In truth," General Rondot continued, "in Algeria's bloody war, the fate of the seven monks was not considered by Algerian military leaders as any more important than the fate of anyone else, even if Franco-Algerian relations were to suffer from the poor handling of the affair or, even worse, from a fatal outcome."

Finally, the general delivers his verdict: "For very (too) long, and for tactical reasons, .and his groups benefited from a relative tolerance on the part of the Algerian services: he helped (probably involuntarily) to engineer the splintering of the GIA and to foment internal strife between the armed groups."

Rondot observed: "In order to remedy this failure, the DCE must eliminate, by all means available, Djamel Zitouni and his cronies. It is our duty to encourage this and perhaps even to impose it." Djamel Zitouni died in July 19961, a month after the funeral of the Tibhirine monks, leaving a mystery that continues over the true conditions under which the Trappists met their ghastly fate.

-------------------------

1: Akin to a regional war lord (emir), Zitouni organised, among other actions, the hi-jacking of an Air France flight in December 1994. He was killed by followers of the emir of the Medea region with whom he had a long-standing feud.

English version: Patricia Brett