The award-winning French actress Adèle Haenel has accused the film director Christophe Ruggia of “touching” and “sexually harassing” her during a period when she was aged between 12 and 15. In this investigation by Mediapart, Haenel, now 30 and who was an unknown child actress when she worked with the director on the 2002 film Les Diables (English title, The Devils), speaks publicly for the first time about the actions of the film-maker, who was then aged 36 to 39, which she describes as “paedophilia”.

The actress, acclaimed for subsequent roles in Water Lilies (2007), House of Tolerance (2011), Suzanne (2014), and Love at First Fight (2015), said Christophe Ruggia's alleged inappropriate sexual behaviour towards her took place between 2001 and 2004, and which she said she “clearly” considers to be “paedophilia and sexual harassment”. She told Mediapart of the major “hold” that the film-maker had over her during the making of The Devils followed by “constant sexual harassment”, repeated “touching” of her thighs and body and “forced kisses on the neck” which she said took place in the director's apartment and in hotel rooms during several international film festivals.

Adèle Haenel told Mediapart that for many years she felt unable to speak out about her experiences but finally decided to do so after seeing the Leaving Neverland documentary about Michael Jackson on HBO in March 2019. But she said she does not want to pursue her alleged attacker through the criminal courts, because the legal system “convicts so few attackers”. She said: “The legal system ignores us, we will ignore the legal system.”

Christophe Ruggia, a prominent director in independent French cinema, declined Mediapart's repeated requests (see the Boîte Noire section, bottom of page).for an interview and nor did he respond to Mediapart's detailed questions submitted in writing. But in a statement issued on October 30th via his lawyers, Jean-Pierre Versini and Fanny Colin, the filmmaker declared, “I categorically deny having carried out any harassment or any form of [inappropriate] touching of this young girl who was then a minor”. In the written statement Ruggia said: “You have tonight [editor's note, on October 29th after a phone call with his lawyer] sent me a lengthy 16-point list of questions about what would have been the professional and affectionate relationship I had, more than 15 years ago, with Adèle Haenel, of whose great talent I was the 'discoverer'. The systematically tendentious, inaccurate, fictionalized and sometimes defamatory version that you have sent me does not leave me able to provide you with responses.”

In her interview with Mediapart, Adèle Haenel described how initially she felt a deep, lasting and indelible “shame” about what she says happened to her. This then turned to a cold “anger” which stayed with her for years. Finally, “little by little” she found peace because, she said, she had to “get through all that”. Then in March 2019 the anger returned “in a more constructive way” when she saw the documentary on the late Michael Jackson in which damning witness accounts accused the singer of crimes of paedophilia and revealed the singer's mechanism for exerting control over others.

“That made me change the perspective on what I'd gone through,” she said, “because I had always made myself think that it had been a story of un-reciprocated love. I had always stuck to his fable about how 'it's not the same with us, the others couldn't understand'. And I also needed that time so that I was able to speak about things without making an absolute drama of it either. That's why [I'm doing this] now.”

The actress, who was first interviewed at length for this investigation in April 2019, took her time weighing each word. She often paused some while before continuing. But her voice bore no trace of hesitation. “I'm really angry,” she said. “But the issue isn't so much me, how I survive this or not. I want to talk about an abuse which is unfortunately commonplace, and attack the system of silence and collusion behind it which makes it possible,” she said. The actress said that she had to speak out because “keeping silent had become unbearable” and because “silence always plays in favour of the guilty”.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Mediapart's investigation, which was carried out over a period of seven months and involved interviews with more than 30 people (see the Boîte Noire section, bottom of page), has pulled together many documents and individual accounts that support the actress's story, including letters in which the director speaks of his “love” which was “sometimes too much to bear”. During the filming of The Devils and then in later years several people tried raise the alarm over the director's attitude towards the actress, but they say that no-one listened.

Christophe Ruggia, now aged 54, has become one of the leading names in French independent cinema and is as well-known – perhaps better-known – for his activism as for his films. He has defended the cause of migrants, the position of short-term contract workers in the film industry and the case of Ukrainian film-maker Oleg Sentsov, who was imprisoned in Russia for five years. Until June 2019 he was co-president of the French filmmakers association the Société des Réalisateurs de Films (SRF), and he is described by those who know him as a “passionate activist who wants to save the world”, a “director with constant intensity” whose films feature children with difficult backgrounds.

Adèle Haenel made her film debut in Ruggia's second feature-length film The Devils, which was released in 2002. Today, she has already won several French film awards – Césars – and starred in 16 films screened at the Cannes film festival under the directorship of celebrated filmmakers who include the Dardenne brothers Jean-Pierre and Luc, Céline Sciamma, André Téchiné, Bertrand Bonello and Robin Campillo.

In December 2000, when Haenel was 11-years-old, she split her time between her classes at school in the suburb of Montreuil, east of Paris, her drama classes and her judo training. It was after attending a casting session with her brother that she landed the lead role in The Devils. “The kid was exceptional, she was one of a kind,” recalled Christel Baras, the director of casting for the film who has since remained a friend of the actress.

At the time both the girl and her parents were delighted. “It was a fairytale, it was absolutely unbelievable what had happened to us,” said her father Gert. Adèle Haenel herself later described the feeling in a personal diary account written several years later, in 2006, and which Mediapart has seen. “I feel full of new importance, I'm going to make a film,” she wrote. The girl spoke of the “novelty”, of it being a “dream”, and of the “privilege” of being “alone on the set, at the centre of attention of all these adults”, and to “stand out from the crowd”. The youngster also wrote of her “passion” for theatre and her “little chats with Christophe [Ruggia]” who “took her in his car”, and who was “always inviting me to eat at a restaurant” even though she had been “ashamed” the first time because she did not have enough money to pay.

“To me he was a kind of star, a bit like a god who came to Earth, because behind it there was the cinema, power and the love of acting,” the actress told Mediapart. Her family, who were middle-class intellectuals, “suddenly became exceptional”, she said. “And I went from being a normal child to someone with the promise of being 'the future Marilyn Monroe' according to him.” At the family home Ruggia was treated with great honour. “He was a good director, on the Left, he'd just made Le Gone du Chaâba, a very good film. We trusted him,” said her mother, Fabienne Vansteenkiste.

The script for The Devils, which is a disturbing film and punctuated by nude scenes, did not trouble the girl's parents. The film depicts the incestuous love between two runaway orphans Joseph (played by Vincent Rottiers) and his sister Chloé (played by Adèle Haenel), who is autistic, mute and allergic to any physical contact. Christophe Ruggia has never hidden the partly autobiographical nature of this film which he described in the press as a “compromise between a hard reality experienced by my two best friends, and mine”.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The on-screen performance by the two young actors came after six months of work before filming even began. These special exercises, overseen by the director and his assistant director – his sister Véronique Ruggia – were aimed at “giving them confidence so they can act difficult things: autism, awakening sensuality, nudity, the discovery of their body,” the director explained to the magazine TéléObs on September 12th 2002. “The three of us have developed an extraordinary bond.” In all, including preparation and the promotion of the film, “the children were removed from their family for nearly a year,” Ruggia said at the time. “So the bonds are very strong.” Several people close to the actress are convinced that the “hold” the director had over Adèle Haenel was forged during this “conditioning” and this “isolation”. According to the actress herself, this was to pave the way to more serious behaviour after the film came out.

Among the 20 or so members of the film production team that Mediapart has spoken to, some said that they had no clear recollection of the shooting of the film or did not want to reply to questions. Others stated that they saw “nothing noteworthy”. This included producer Bertrand Faivre, the actor Jacques Bonnaffé – who spent several days on the set – and the film editor Tina Baz. The latter, who remains close to Ruggia, described the director as “respectful” and someone who throws himself “absolutely into his work” and who had a “paternal relationship without any ambiguity” with Adèle Haenel.

On the other hand, many others described a director who was both “all-powerful” and “infantile”, “immature”, “oppressive”, as someone who “subjugated” others, who “monopolised”, was “invasive” with children, and who isolated himself in a “bubble” with them. Nine people described what they saw as the director's “hold” or powerful “ascendancy”, his “manipulative” relationship with the two actors, who saw him as “Father Christmas”.

During filming of The Devils, which started on June 25th 2001, Christophe Ruggia is said to have reserved special treatment for Adèle Haenel, by then aged 12, and who according to several witnesses was “protected”, “looked after” and “too mollycoddled”. The actress herself recalled: “It was special with me. He clearly played the love card, he told me that the camera loved me, that I had genius. For a time I perhaps believed such talk.”

“I always saw their great closeness,” said her co-star Vincent Rottiers, who remains a friend of Ruggia. He remembered how “Adèle kept sticking close to him, like the top of the class with her teacher” and that “Christophe took more time with her, conditioning her”. Rottiers added: “It was just for her, to the point that I was sometimes jealous. But I told myself that it was special because she was playing someone with autism. In hindsight, I see it differently.”

Éric Guichard, director of photography during the shooting of The Devils, saw no “inappropriate gesture” but said he had “rarely” seen as “close a bond” as existed between the director and the young actress who was “taken over by her role”, “captivated by Christophe” and who “only confided in him”. Guichard described an “obvious ascendancy” on Ruggia's part but one which was “in keeping with the making of a cinema film” and he attributed it to “the difficulty of Adèle's role”.

Actress Hélène Seretti, who was employed as an acting coach during filming, and who has kept in touch with Adèle Haenel, thought the director “bonded too much” with the young actress. “He was tactile, putting his arms on her shoulders and sometimes giving her kisses,” she recalled. “For example he'd ask her 'and what are you going to eat, my darling?' Over time I began to tell myself that that this was not a relationship that an adult should have with a child … it bugged me.” The acting coach said that she was “not relaxed” about it and remained “on alert”. However, she was restricted to a role she described as being more of a “nanny” far away from the set. “Christophe Ruggia had a privileged relationship with the two children, so he told me clearly: 'You don't deal with them, I've worked with them for months to prepare for this shoot.' When he was preparing scenes he kept me away,” said Seretti.

A member of the production team, Dexter Cramaix, said that relations between the director and his two young actors were not in the “right place”, and were “too affectionate” and “exclusive” and “beyond the purely professional”.

“Among ourselves we said that something wasn't normal, that there was a problem. It's often said of directors that they must be in love with their actresses but Adèle was 12-years-old,” he said.

Laëtitia, the production manager, who quit the film at the end after suffering “burn out”, confirmed that view. “The relations that Christophe had with Adèle were not normal. You got the impression that she was his fiancée. You almost didn't have the right to approach her or talk to her because he wanted her to stay permanently in her role,” she said. “He alone had the right to have real contact with her. In the [production] team we were very uncomfortable.”

The film's script girl, Edmée Doroszlai, said that she expressed similar concerns to one of her colleagues. “I said to him, 'look, you'd say they were a couple, this isn't normal'.” She said she “raised the alarm” after noting the “children's exhaustion and mental suffering”. She added: “It went too far. In order to protect them, I got the filming stopped on several occasions and I tried to contact the DDASS [editor's note, the former health and social services department, restructured in 2010].”

Cameraman Jérôme Plon said of the director: “He manipulated the children.” Plon left the shoot after a week with the impression that the director was operating “a bit like a guru” and that he was “taking possession a bit” of people. He said that because of his concerns he spoke about it with a female friend who was a children's psychoanalyst.

'I didn't move, he was annoyed with me for not consenting'

During a film shoot, how does one determine the subtle border between the special attention given to a child who is the main actress in the film, a relationship in which someone has a hold over someone, and possible inappropriate behaviour? At the time The Devils was filmed, several members of the production team struggled to find the right words for what they were observing. Their task was further complicated by the fact that none of them saw an explicit gesture with “sexual connotations” made by the director towards the actress. “I was wavering all the time between 'what's happening is not right at all' and 'perhaps he's just fascinated',” said Hélène Seretti, who was then aged 29. “I was young, I didn't trust myself, it would be different today.”

Production manager Laëtitia was also full of doubts. “It's very difficult to tell yourself that the director for whom you're working is potentially abusive, that there's manipulation. I sometimes told myself: 'Was I dreaming? Am I crazy?' And no one would have thought to meddle in his relationship with the actors, to dare to say a word, because that's part of the creative process. That's where the possibility of abuse on film shoots – whether physical, moral or emotional – can arise,” she said.

Two members of the production team told Mediapart that they were marginalised after expressing concerns about the actress. Hélène Seretti said that she was “made an enemy” by the director for expressing her doubts. One morning, after Adèle Haenel had had a “bad night”, and after the actress's mother had questioned the director's behaviour, Hélène took the opportunity to have a word with Ruggia. “It was difficult to really state things in front of him, I tried to explain that Adèle wasn't well, that it was going too far, that we couldn't go on like that,” said Seretti. “He replied: 'You want to screw up my film, you don't realise the privileged relationship I have with them’.” From then on, she claimed, the director “no longer spoke a word” to her and that the “rest of the shoot wasn't easy”. She said she tried to raise her fears with several members of the production team, but that the replies were along the lines of “That's cinema, it's the relationship with the actor” or simply that the director is the boss.

“You didn't dare challenge the director, I was afraid and I didn't know what to do nor who to talk to,” Seretti added.

Christel Baras, the director of casting, said that she was “removed” from rehearsals after a remark she made in the summer of 2001, before filming started. “We were in the entrance hall of Christophe’s [Ruggia's] apartment. Adèle was sat on the sofa further along. He wanted me to go, for me to leave them. I was very uncomfortable, disturbed. It was the way in which he was looking at her, what he was saying. I told myself: 'It's getting out of control here,'” she said. “I didn't think about something sexual in nature at the time, but I saw his hold over the child.”

The casting director said that when she left the apartment she “looked straight into his eyes” and warned the director: “She's a little girl, a little girl! She's 12-years-old!” After that episode Ruggia, she said, told her that he “no longer wanted her” on the set. Some years later, with hindsight, she came to see this as a “banishment” because she was “dangerous”. Was Christel Baras, who has a strong personality, judged too invasive a figure on the shoot or was she an obstacle to the exclusive relationship that the director wanted to have with his actress?

Baras's “unease” was reinforced after the film came out when she met the girl “two or three times” at the director's home. In particular, Baras saw her there one Saturday night when she turned up unexpectedly looking for a DVD. “It was 8pm-8.30pm, I was uncomfortable and I said: 'What are you doing here Adèle, haven't you seen the time?'” she recalled. She said that Adèle was “under a hold, each time she went back there”. The casting director later worked with Ruggia on another film involving adult actors.

Asked to explain why no-one attempted to challenge Ruggia's behaviour, a number of people questioned by Mediapart spoke about the “all-powerful” director. Some said they were afraid that their contract might not be renewed or that they would be blacklisted in an industry where employment is unstable. Others said that they put his attitude down to the particular relationship of the director with his actors, of his “working methods” his attempts to “bring out his actors' acting”. And most said that they were preoccupied by a shoot which they described as “difficult” and “exhausting”, which had little funding and which involved working six days a week.

The actress's mother, Fabienne Vansteenkiste, also felt concern about what was happening. She told Mediapart of the “unease” she felt during her visits to the shoot in Marseille. “In the Vieux-Port [editor's note, the old port area of the city] Christophe was with Adèle on one side and Vincent on the other with his arms around the shoulders of each of them, giving them kisses. He had a strange attitude for an adult with children,” she said. On the drive back home she was worried and stopped at a fuel station to find a telephone to call her daughter and ask her “what was going on with Christophe”. Her mother recalled: “Adèle told me where to go, along the lines of 'You poor thing you really have a twisted mind’.”

The following night the schoolgirl had a fit of hysterics. “I couldn't be calmed down at all, I was crying like some kind of animal, I was hurt,” Adèle Haenel told Mediapart. “The next day I was ill at ease on the set and we shot the scene many times even though it was simple.” Hélène Seretti remembered the episode too. “There was a dichotomy in her, she sensed the turmoil– without being able to name it – and at the same time she kept on repeating that she wanted to carry on right to the end of the film.”

Haenel claimed it was after the making of the film, which ended on September 14th 2001, that the exclusive relationship with the director – she was then aged 12, he was 36 – “slipped into something else”. According to her account, some “touching” took place during regular weekend meetings at the director's Paris flat, to which her father sometimes drove her. Christophe Ruggia, who had a well-stocked DVD library, took charge of the young actress's film education, read the scripts that she received, and advised her. The actress said that the director “always did things the same way”. This meant “white chocolate fingers and Orangina” put on the little table in the living room, then a conversation during which he would “veer off” with gestures which “little by little took place more and more”.

The actress has detailed recollections of that time. “I always sat on the sofa and he was opposite in the armchair, then he came onto the sofa, right next to me, kissed me on the neck, felt my hair, stroked my thigh down towards my genitals, started to put his hand under my T-shirt towards my chest,” she said. “He was excited, I pushed him off but that wasn't enough, I always had to move place.” She said she would move first to the other end of the sofa, then stand by the window “as if nothing were up”, and then sit on the armchair. Then “as he was following me, I ended up sitting on the footstool which was so small he couldn't come next to me,” said Haenel. The actress said that it was clear that he was “looking to have sexual relations with me”. She said that she does not remember “when the [director's] gestures stopped” and said that “his caresses were something [that happened] constantly”.

She described the “fear” which “paralysed” her on these occasions. “I didn't move, he was annoyed with me for not consenting, and each time that triggered crises on his part”. These involved trying to make her “feel guilty”, she said. “He started from the principle that it was a love story and that it was reciprocated, that I owed him something, that I was a real minx not to play along with the game of this love after all he had given me. Every time I knew that this was going to happen. I didn't want to go there, I felt really bad, so dirty that I wanted to die. But I had to go there, I felt indebted.”

Her parents were apparently untroubled by the visits. The actress's mother, Fabienne Vansteenkiste, said: “I told myself, she's watching films, it's really great that she's picking up this film culture thanks to him.” Haenel’s co-star in The Devils, Vincent Rottiers, explained that he often went to Ruggia's home to talk about cinema and news, sometimes with friends. “Christophe had become my family. My cinema father,” said the actor. “Adèle was sometimes already there when I arrived, I told myself it was strange, I asked myself questions, but without understanding.”

In his statement issued to Mediapart, cited above, Christophe Ruggia said he “categorically denied” any “harassment or any sort of touching”.

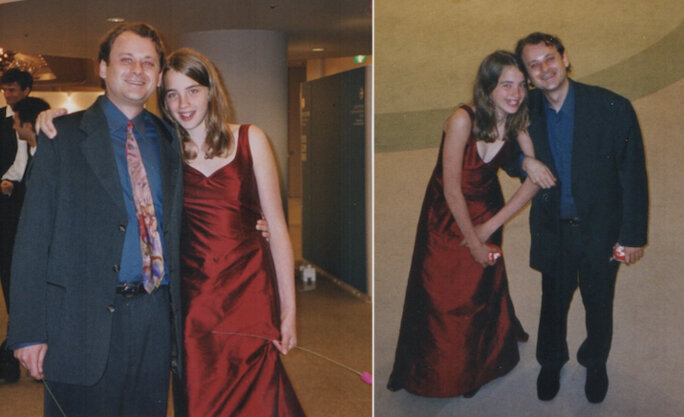

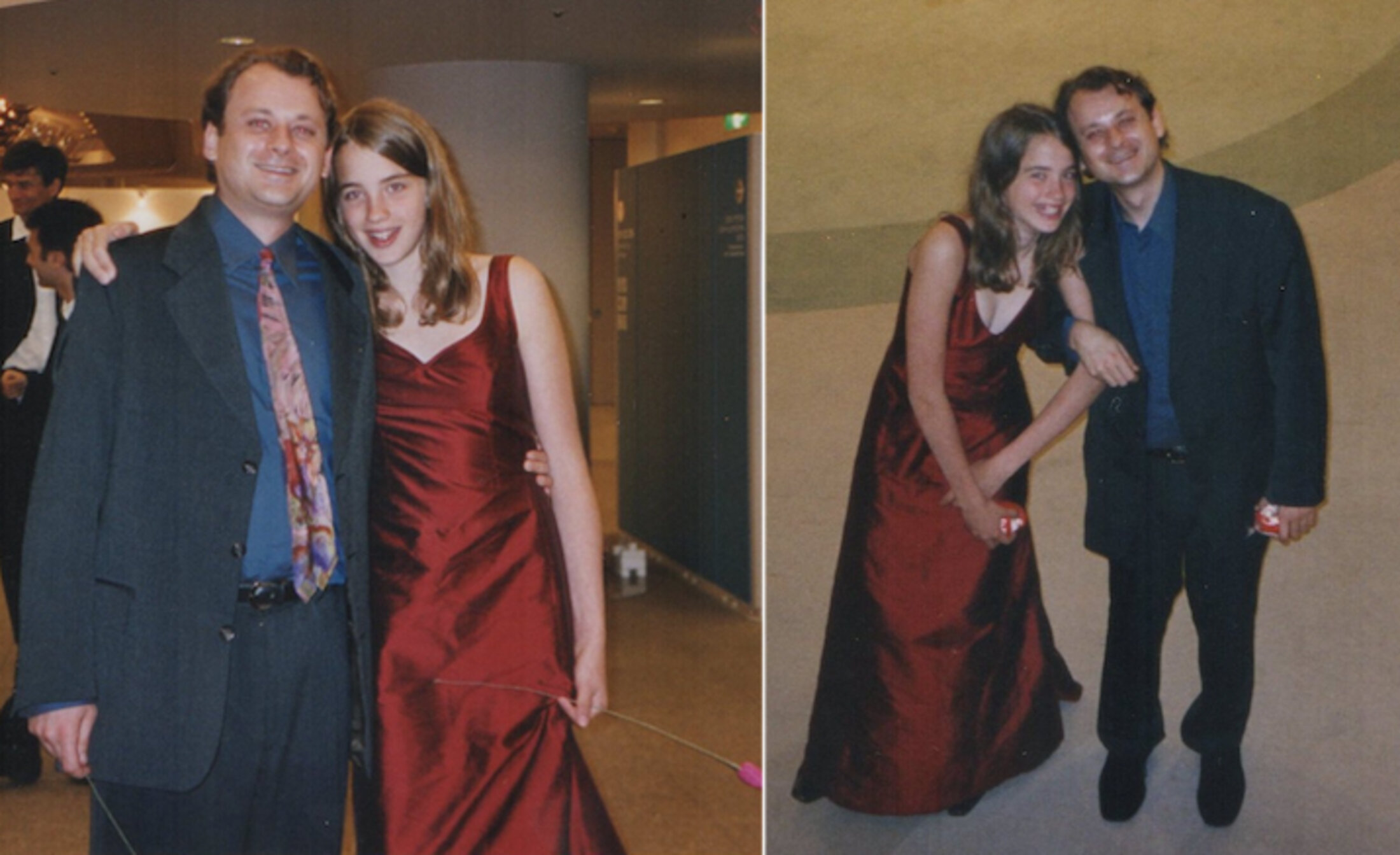

According to the actress the director's behaviour was the same in other private encounters. These were in hotel rooms at the international film festivals that the filmmaker attended with his two young actors after the film came out in 2002: in Yokohama in Japan, Marrakesh in Morocco and Bangkok in Thailand. The actress kept everything from this 'promo' tour – hotel labels, programmes, press reviews – and stored them in a blue folder. It was during this trip that the fascinated 13-year-old discovered aeroplanes, beaches, luxury buffets, photographers' flashing lights and signing autographs. But, she says now, she had not forgotten the “strategies” she had developed in order to escape being “touched” in hotel bedrooms. “When I entered a room I knew where to place myself, so that he didn't come up right next to me,” Adèle Haenel told Mediapart.

The actress detailed the large window sill at the Inter-Continental hotel in Yokohama in June 2002 on which she used to sit “because I didn't want to be on the bed next to him”. “But he came towards me, he came up close, he tried to touch me, he told me 'I love you',” the actress recalled. She described Christophe Ruggia's “declarations” and protestations of “I love you”, made openly, during parties, and his “scenes of extreme jealousy”. But she also described the state of “anguish” that she felt. “One morning I woke up and I started to feel paranoid, I said to myself 'I didn't go to sleep in this bed'.” Mediapart has obtained several photographs taken at the festival in Japan (see below) in which one can see the director in a dinner jacket holding the young actress by the hip, while she can be seen wearing a long evening dress and – a sign of her young age – missing some of her milk teeth.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

Adèle Haenel also recalled a scene which took place at the film festival in Marrakesh in September 2002. She said the director had flown into a “rage” when he discovered that she had “eaten the little chocolate provided by the hotel” while he was making a “declaration of love [to me] in his room”.

“He threw me out the door then opened it again. He was telling me that he loved me, that he was completely mad. I found myself in this drama over there,” she said.

In June 2004, when she was aged 15, Haenel went on her own with Christophe Ruggia to the French Film Festival in Bangkok. She remembered having again to push away his hand which was “squeezing my hip in the tuk-tuk [editor's note, three-wheel motorized rickshaws]”.

“That annoyed him and he wanted me to feel guilty,” she said. In a letter sent to the actress on July 25th 2007 the director referred back to the “great trip full of experience but which completely de-stabilised me” and which referred to “'problems' which became apparent to me in Thailand”.

Christophe Ruggia did not respond to Mediapart’s precise question about what “problems” he was referring to.

In that same year Ruggia had written a script dedicated to her in which the main characters were called “Adèle and Vincent” and which he wanted to give Haenel on her 16th birthday, he said in the letter. In it he explains that he was “terrified” at the idea that the actress might not want to take part in this new film “because of me (seeing how you had had a go at me at certain times over there)”, he wrote. According to the actress, at the time the director exercised considerable control over her. This extended to controlling trivial things, she said, like her habit of passing her tongue over her lip. “He had told me to stop, as in 'it's too sexy, you don't realise what you're doing to me’.”

'Christophe Ruggia told me of romantic feelings for Adèle'

Enlargement : Illustration 7

Adèle Haenel’s account of her relationship with Christophe Ruggia is supported by a number of documents and the recollections of people in their entourage. These include the film director and screenwriter Mona Achache. She told Mediapart of a conversation she had with Ruggia when she was his partner, in the spring of 2011. She said that Ruggia, speaking of the period during the promotional tour of The Devils, “told me that he had had romantic feelings for Adèle”. Achache, who has no personal links with Haenel, said she questioned Ruggia further, after which he detailed one precise incident. “He was watching a film with Adèle. She was lying down, her head on his knees,” Achache recalled him saying. “He had passed his hand up from Adèle’s tummy to her chest, under her T-shirt. He told me he saw a look of fear in her, staring wide-eyed, and that he too became frightened and withdrew his hand.”

Achache said she felt “groggy” and ill at ease at Ruggia’s “manner of telling the story” of the incident. “He felt strong, honest, rightful to have known [the need] to withdraw his hand,” she said. “He tried to be humorous while telling me that he was lost in love and that she drove him to distraction.” Achache said that in face of her questions, Ruggia became “a little evasive” and was “minimising the thing”, adding: “He did not realise that to have interrupted his gesture changed nothing in the trauma that he might already have caused. He didn’t place in question the very principle of these meetings with Adèle, nor the coming into being of a relationship which made it possible that a child could be lying languidly on his knees watching a film. He remained focalised on himself, his pain, his feelings, without any realisation of the consequences of his general behaviour upon Adèle.”

Achache said she was “staggered” by that conversation, and subsequently broke off her relationship with Ruggia, without telling him why. She said she had largely kept silent about what she had learnt because she believed it “didn’t seem right to talk in place of Adèle Haenel” and also because what she knew was only what Ruggia “had wanted to tell me”. However, Achache did mention the conversation to her close friend, the French filmmaker Julie Lopes-Curval. Questioned by Mediapart, Lopes-Curval said: “We were at Mona’s place. She told me that he [Ruggia] had not been straight with Adèle Haenel. She didn’t tell me everything, but she was bothered about something. There was a malaise, it was obvious.”

Christophe Ruggia did not reply to questions submitted to him about Mona Achache’s account.

Antoine Khalife, who represented the body that promotes French films abroad, UniFrance, and who was present at the 2002 Yokohama festival in Japan, reportedly also expressed unease at Ruggia’s relationship with Haenel. French film director Céline Sciamma recalled comments he made when she met him during the January 2008 Rotterdam international film festival, when she was presenting her first feature-length film Naissance des Pieuvres (English title, Water Lilies) which starred Adèle Haenel. “I didn’t know him,” said Sciamma. “He told me, ‘I like your film a lot. I was also relieved to have news of Adèle Haenel, happy to see that she was not dead’.”

“He told me that he had worried a lot about her,” continued Sciamma. “He told me about Yokohama in great detail: Christophe Ruggia who had her dancing in the middle of the room, who was declarative. He was marked [by the experience].”

According to casting director Christel Baras, Khalife also spoke to her about what he saw in Yokohama when they met on the sidelines of a UniFrance event in Hambourg, ten months after his conversation with Sciamma in Rotterdam. “He told me, ‘I am very happy to see you, because I have always been very bothered about something,” she recalled. “‘I did the promotion for The Devils at Yokohama, I never understood the relationship that Christophe Ruggia had with that young actress. One couldn’t speak to her, nor approach her. What was happening?’”. Baras added: “I said to myself, ‘that’s it, I’m not mad’.”

Contacted by Mediapart, Antoine Khalife did not offer any comment on his reported comments (see Boîte Noire, bottom of page).

Enlargement : Illustration 8

Mediapart has gained access to two letters written by Christophe Ruggia to Adèle Haenel, one addressed to her in July 2006 and the other in July 2007. In the letters, Ruggia wrote of his “love” for her, which he described as being “sometimes too heavy to bear” but which “has always been of an absolute sincerity”. Ruggia declared that, “I miss you so much Adèle”, and that, “You are important to my eyes”, and, “The camera loves you like crazy”. The director said he had “to continue to live with this hurt” but hoped for a “reconciliation”.

“I even asked myself several times if finally it would be me who will stop with cinema,” he wrote. “I still sometimes ask myself this, when I am hurting too much.”

In 2005, before those letters were written, Adèle Haenel had told Ruggia that she was ending all contact with him. Her announcement was made during yet another afternoon she had spent at his Paris home. “That day, I got up and I said, ‘This must stop, it’s going too far’,” she told Mediapart. “I couldn’t bring myself to say more. Until then, I hadn’t put words to it, so as not to shock him, so that he didn’t see himself in the process of abusing me.” She said Ruggia showed an uneasiness that day. “He didn’t feel well. He said to me, ‘I hope things are alright’.”

That incident was confirmed by Haenel’s former boyfriend during her final years at secondary school. Agreeing to be interviewed by Mediapart, Benjamin asked for his last name to be withheld for professional reasons. “There was a meeting at Christophe Ruggia’s home which was different to the others, which drove her to talk to me about it,” he said. “She had been upset.” Benjamin recalled that Haenel had initially “compartmentalized her two lives” and displayed “a discomfort, a feeling of shame, of guiltiness” with regard to Ruggia, but that after the incident she spoke to him of the director’s “guilt-inducing declarations of love”, his “permanent hold” over her and “scenes where she had been ill at ease, on her own at his home”. Benjamin said he put “pressure” on her to cut off her links with Ruggia.

Haenel said it was Benjamin’s “incomprehension, even though clumsy” which was the spark that gave her the force to break off with the director. “I had met this boy, begun to have a sexuality, and the tale of Christophe Ruggia no longer had hold,” she said. She recalled that at the time, as a disoriented teenager, the only way out of the situation that she could imagine was either the death of the director or herself, “or the renunciation of everything”. In the end, she decided to abandon her future as a film actress; it was in early 2005 that she wrote to Ruggia explaining that she did not want to visit him at home anymore, and that she was putting a stop to ner activities in cinema.

That letter was written with the feeling that she was giving up on “lots of things”, including “a part of myself”, Haenel recalled. “I had acting in my belly, it was what made me feel alive,” she said. “But for me, it was he who was cinema, him who had put me there. Without him I was nobody, I fell back into an absolute nothingness.”

Enlargement : Illustration 9

Ruggia wrote back to Haenel saying that he had received her letter “right in the heart”. He tried to revive the contact between them through Haenel’s close friend Ruoruo Huang, then aged 17. “We lunched together at the Cantine de Belleville [restaurant],” Huang told Mediapart. “I wasn’t in the know about anything. In the middle of the conversation he said Adèle was no longer speaking to him. He tried to obtain news and, implicitly, to pass on a message.”

Haenel, meanwhile, cut off her cinema contacts, dropping her agent and not replying to screenplays sent to her or invitations to castings. “I chose to survive and head off alone,” she said, adding that the decision left her in a state of “enormous ill-being”, a period of depression with suicidal thoughts and a strong fear of bumping into Ruggia. Indeed, she did run into him on three further occasions, once at a demonstration close to the Sorbonne university in Paris in March 2006, then in a baker’s store in 2010 and, in 2014 after she had renewed her cinema career, at the Cannes Film Festival. According to two people who had witnessed an encounter between the two, Haenel was gripped by “an intense reaction”, in a state of “panic” and “confusion”.

“I continued to feel fear in his presence,” Haenel told Mediapart. “Meaning, in concrete terms, a heart that beats fast, hands that sweat, thoughts that become clouded.” She said that for ten years she felt “about at breaking point” and hardly coping.

Her personal diaries trace this condition. In 2006, when she was aged 17, she wrote of the “monstrous chaos” inside her head and the need to write things down in order to “remember, to clarify things” because she had difficulty in remembering “exactly what has happened”.

In 2001, she had jotted down “I have become the centre of attention”. In 2002 she wrote: “Festival + shifty Christophe => I feel alone, strange.” In 2003 she noted: “I have a secret, I never speak of my life. I am in a world of adults.” For 2005, she wrote “I am no longer seeing Christophe”, and the following year she noted: “Sometimes I think that I will succeed in telling everything […] I cannot stop myself from thinking about death.”

'Like so often, everyone closed their eyes'

There are obvious questions as to why Adèle Haenel’s family did not see the signals of her distress. Her brother Tristan said that at the time he believed that her “estrangement” and fits of anger were due to puberty, although he said that he had found “something strange” about Ruggia’s behaviour, and also his sudden absence. “At one moment, Christophe was simply no longer around,” he recalled. Haenel’s parents admit to having had a blind confidence in the director over the many years he was close to their daughter. Her father now says that he “became conscious much later of the hold Christophe Ruggia had on her”, adding: “For Adèle, he was everything and, all of a sudden, she no longer wanted to know about him. But it was difficult to talk with her during adolescence.”

Haenel’s mother said she was taken up with demanding professional activities and daily necessities. “At the time I was a teacher, I was also making advertising films, I became engaged in politics and I was never around.” She said that it was when, in February 2005, she saw her daughter’s fear as the phone rang in the family home, that she understood there had been “abuse”. She recalled: “Adèle became suddenly tensed. She told me, terrified: ‘I’m not here. Answer that I’m not here!’ When she saw that it was one of her friends, she relaxed and took the call. I asked her ‘Are you frightened that it’d be Christophe?’. She told me, ‘Yes, but I don’t want to talk about it’.” Her mother said she was “very worried” about the situation but that her attempts to talk about it with her daughter were in vain.

About that period, Adèle Haenel says today: “I felt so dirty at the time, I was so ashamed, I couldn’t speak about it to anyone, I thought it was my fault.” She said she feared “disappointing” and “hurting” her parents. “Silence has never been without violence,” she added. “Silence is an immense violence, a gagging.”

Enlargement : Illustration 10

Haenel said she threw herself into her studies, so that “no-one would ever again think in my place”, adding that “I could have learnt Thai boxing, I did philosophy”. She said she had support “from no-one” as she grappled with “solitude, guiltiness”. That changed when she met the film director Céline Sciamma and returned to cinema acting for Sciamma’s first movie Naissance des pieuvres (English title, Water Lilies), which was released in 2007. Some close to Haenel describe that experience as being the first steps of a “renaissance”.

It was casting director Christel Baras – who in her own words was at the time “sick of this waste and for having recruited Adèle for Christophe Ruggia’s film” – who had contacted Haenel in 2006 to propose she take part in Sciamma’s production. The young actress had just celebrated her 17th birthday, and Baras encouraged her to take up the role in a film that would put the past behind her and open up a positive future. Baras told her that the production involved only women and described the director as “extraordinary”. Haenel recalled: “I came back – fragile, but I came back.”

Haenel soon confided in Céline Sciamma, with whom she would begin a romantic relationship, mentioning the problems encountered on her previous film. “She told me she wanted to make the film, but that she wanted to be protected because something happened to her on her preceding film, that the director did not behave well,” Sciamma told Mediapart. “She doesn’t go into detail, she expresses herself with difficulty, but she speaks to me [sic] about consequences that this had, her solitude, her putting a stop to cinema. I understand then that I am the guardian of a secret.”

That secret was revealed at the end of the shooting of Water Lilies, which was made with two members of the production staff who took part in the filming of The Devils, namely casting director Christel Baras and acting coach Véronique Ruggia, the sister of Christophe Ruggia. Céline Sciamma said she remembered how she was alarmed to discover, in mid-October 2006, the two women “asking themselves, concerned, up to just what point things had gone, if Christophe Ruggia had had sexual relations with this child”.

“Each of them had lived with this question for years, and remained in the secret and guilt regarding this story,” Sciamma said. “I also saw the admiration and hold that [Christophe] Ruggia generated, because he’s the director, their employer, their brother, their friend.” Sciamma said that during the discussion between the two women, Véronique Ruggia was “shattered, very affected”, asking “if Adèle had said ‘no’”, adding: “One has the right to fall in love but, to the contrary, when one says ‘no’ it’s ‘no’.”

Sciamma and Haena became lovers during the shooting of the film, and it was while watching The Devils together one evening that Sciamma said she became “fully conscious of the gravity of events” that had affected Haena. The latter had not been able to watch the film in a long while, and Sciamma spoke of her “very upsetting” reaction. “Adèle blew a fuse, faints, shouts [sic]. It was such pain. I had never seen her like that.”

Sciamma, who was then aged 27, encouraged Haenel to speak out about her experiences. The actress began by talking to actress and acting coach Hélène Seretti, to Christel Baras and Véronique Ruggia. Haenel recalled what she describes as her “confusion” when talking to Véronique Ruggia. “We spoke for a long time, at her place. I was really not well, [and] embarrassed to have to tell her this. I didn’t manage to well to talk, and I excused Christophe a lot, saying ‘No, but it’s not so bad, he was just a little unhinged’. Véronique was affected, she was ashamed and felt guilty I think. But the seriousness of the thing had to be put in perspective.”

Contacted by Mediapart, Véronique Ruggia confirmed that she had spoken with Haenel about her experiences, and also with Céline Sciamma. “I was completely taken aback,” she recalled, adding that she understood from the conversation that there had been no sexual intercourse involved. She admitted that her recollections were a little “cloudy”.

“It shocked me so much that I have certainly put a handkerchief over the memory of many things,” Véronique Ruggia said. “I was also traumatised by this story, to have been there without seeing things that there may perhaps have been. She said she remembered that Haenel had told her that she had spoken to Christel Baras and asked her the question, “‘But what did the adults do on the shoot?’”.

“I discovered lots of things that day about which I had absolutely no awareness of,” she continued. “I spoke to my brother about it at the time when Adèle made those statements to me.” She told Mediapart she wanted to discuss the subject with her brother before answering further questions, and that “I prefer that he speaks to you” (see more in the Boîte Noire section at the bottom of this page).

Adèle Haenel told Mediapart that in 2008, together with her then partner Céline Sciamma, she sent another letter to Christophe Ruggia. “The letter denounced Ruggia’s fiction and related the events in their crude and cruel truth,” said Sciamma. “Adèle described the events, the gestures, the avoidance strategy. She placed him in face of his acts. It was explosive.” The pair said there was no response to the letter.

Christophe Ruggia did not respond to specific questions Mediapart submitted to him about the letter.

Enlargement : Illustration 11

Six years later, in 2014, Céline Sciamma was elected as co-president, alongside Christophe Ruggia and Pierre Salvadori, of the French film directors’ association, the Société des réalisateurs de films (SRF). She said she spoke to other members of the association about her unease over her situation but that she did not want to take action in the place of Haenel.

Haenel said she had tried to talk about her experiences with Ruggia to people she and Sciamma knew within the SRF but, she said, she was not listened to. “What has also for a long time made speaking out impossible is that I was repeatedly told, even before I said anything at all, that Christophe was ‘someone nice’, that he had ‘done so much for me’, and that without him I would be ‘nothing’,” said Haenel. “People don’t want to know, because it implicates them, because it’s complicated to tell oneself that the person with whom one has laughed, smoked cigarettes with, who is committed to the Left, did that. They want me to keep up appearances.”

She said that over the years she has been the object of comments that expressed unease, or denial, and even which implied her own guilt, including from acquaintances in the world of cinema, and feminists. Her father, she said, encouraged her “to pardon” and above all not to tell her story to the media.

Others, meanwhile, have offered help, including filmmaker Catherine Corsini, a current co-president of the SRF, who confessed to her shame at not having taken the measure of Haenel’s case. Corsini told Mediapart that she had learnt two years ago that Haenel had wanted to “denounce inappropriate behaviour by Christophe Ruggia” to members of the SRF, who she said did not know how to deal with the issue. “For many, it was unimaginable,” she said. “And it was difficult to intervene without knowing what Adèle Haenel wanted to do. Céline Sciamma suffered from the situation.”

Corsini said she was “distraught” when she learnt in April this year of the “suffering” of the actress. “Like so often, everyone closed their eyes or asked no questions,” she added. “That must ask questions of each of us, individually.”

Christophe Ruggia was for many years re-elected to the board of the SRF, and was appointed, variously, as co-president and vice-president on several occasions between 2003 and 2019. In October 2017, he co-signed, along with 21 other filmmakers, a statement issued by the SRF welcoming the “wind of change” that the then unfurling allegations of sexual assault and harassment against US film producer Harvey Weinstein had brought about. Ruggia also co-signed another statement from the SRF criticising the Cinémathèque française (French cinema archive and film heritage centre) in the controversy surrounding its planned retrospective exhibitions of the works of Roman Polanski, wanted in the US on charges of raping a 13-year-old girl, and the late French director Jean-Claude Brisseau, who was convicted of sexual harassment.

'In my current situation I cannot accept silence'

Adèle Haenel and Céline Sciamma say they also spoke with Christophe Ruggia’s producer, Bertrand Faivre, on the sidelines of a prize-giving ceremony in Paris by the French cinema and cultural activities funding institute, the IFCIC, on December 8th 2015. They said that during the evening event, Faivre engaged in a conversation about The Devils, when he expressed surprise that Haenel never spoke with journalists about her first film. He also claimed personal credit for having protected Haenel, during the Marrakesh film festival, from a photographer who wanted to do a photo shoot alone with her. “He boasted about saving me from the potentially paedophile behaviour of the photographer,” Haenel told Mediapart. “As a result, it came straight out, I told him ‘As it happens, no, you didn’t protect us’, then I said that Christophe Ruggia behaved badly with me.”

Haenel and Sciamma said Faivre was “dumbfounded” and “perturbed” at what Haenel told him, commenting, “It’s not possible”. Sciamma said her response to that was: “Yes, she just told you so, extremely clearly, listen to her. Now you know. You’ll have to ask yourself questions.”

Contacted by Mediapart, Bertrand Faivre said he remembered being “stupefied” by what he called the “anger” and “violence” of Adèle Haenel that evening nearly four years ago, but said that nothing “explicit” was talked of, and that Céline Sciamma “minimised things”.

“I left from that discussion saying to myself that something serious happened between Christophe and Adèle, but I didn’t put a sexual connotation on it,” he said, adding that when he arrived home he spoke about the conversation with his wife and later questioned Christophe Ruggia. “He sent me packing, told me that yes they had fallen out but that was not any of my business. I didn’t take things further.” Faivre said he ran into Haenel “several times” later and noticed her “coldness” towards him but that she did not raise the subject again.

Faivre said he was “flabbergasted” by Haenel’s account today. Speaking of the making of The Devils, he said: “It [was] a difficult, intense shoot, there was a lot of fatigue, many hours, and a hole in the budget of 1.1 million francs [168,000 euros].” He insisted that “no-one told me of a problem with Christophe Ruggia” during the filming, and that he himself was regularly present at the shoot, as also at the movie’s presentation at the film festivals in Yokohama and Marrakesh, but “noticed nothing that shocked me”.

“I am perhaps in a subconscious denial, but for me there was zero ambiguity,” he added. “He was very close to Adèle and Vincent [Rottiers]. They remained close for several years after the filming. I interpreted that as a director who is careful not to drop children after the film, because the return to their normal life can be difficult.” While Faivre conceded that Ruggia’s work with children was “particular”, he said the director had filmed with “many children” previously and that this inspired confidence in him.

The director of photography during the shooting of The Devils, Éric Guichard, said he had insistently asked why Adèle Haenel did not discuss The Devils in media interviews, and was finally given an answer “in 2009 or 2010” by another person who had worked on the filming. “I understood from that conversation that there had been some concerns with Christophe, some fondling after the shoot,” he told Mediapart.

Haenel’s young co-star in The Devils, Vincent Rottiers, said he had asked himself questions about why Haenel and Ruggia had broken off relations. “I didn’t understand,” he said. “I said to myself that she had her career now.” On June 5th 2014, at a preview presentation in Paris of Haenel’s then latest film, Les Combattants (English title, Love at First Fight), Rottiers met up with the actress. “I said to her, ‘Why did you go away? Did something serious happen, paedophilia? Tell me and we’ll sort it out’,” he recalled. “I wanted her to react. I said one thing to discover the other. I didn’t get my answer, she remained silent.” Three days after that encounter, Haenel transcribed that conversation in a new letter she wrote to Ruggia, but which she never sent. Mediapart obtained access to the letter, in which she details events she says she was a victim of, and in which she uses the word “paedophilia” and the phrase “abuse of someone in a situation of weakness”.

There is sometimes a discrepancy between what Adèle Haenel believes she expressed to people and what they believe to have understood. But over time, for those who leant a sensitive ear to her words, she did not hide that the making of The Devils was a painful experience. In a video interview about her acting in 2010 (in French, here), she underlined the danger of what she called the “grip” of a director “who has brought you towards the light, who brought you knowledge”, their power in “shaping an actor” – and all the more so “when he is little”, adding: “They don’t realise when they go beyond the limits of what they should be doing with someone […] For me, that sort of thing won’t happen to me again, because now I have real-life experience in this kind of relationship […] and also, I have done studies.” In another interview two years later, she said of The Devils that she said she could “no longer watch this film, it was too strange”. In an interview with the weekly magazine of French daily Le Monde published on October 12th 2018 on the release of the film En Liberté ! (English title, The Trouble With You) in which she stars, she spoke of a “traumatic” experience she lived through, one which was “incandescent, crazy, so intense that afterwards I was in shame of that moment”, adding: “It was necessary to ensure continuing to live to reconstruct oneself.”

When the #MeToo movement erupted in the autumn of 2017 in the wake of the first revelations about Harvey Weinstein, several of those close to Haenel thought of her and wondered whether she might take the plunge to liberate herself from her distress. Céline Sciamma was one, and suggested to the actress that perhaps the moment had arrived. But Haenel was not then ready to do so, nor when, one year later, she gave the aforementioned interview to Le Monde. “The journalist asked me, ‘What happened with The Devils?’,” recalled casting director Christel Baras. “I called Adèle. ‘Are you going to talk about it or not?’ She told me no.”

Adèle Haenel explains today: “I didn’t know how to talk about it, and the fact that is close to a case of paedophilia made the thing more complicated than a case of harassment.”

Enlargement : Illustration 13

The decisive moment for Haenel came in the spring of this year, after viewing the documentary about Michael Jackson and also when she learned that Ruggia was preparing a new film, entitled ‘L'Émergence des papillons’, in which the two lead characters have the same first names as those in The Devils. “It was really abusive,” she said. “This feeling of impunity. For me, it meant that he completely denied my story. There comes a time when the pretences are no longer tolerable.” She said she also worried that the acts she says she was a victim of might recur, for the new film focuses on a story of two adolescents.

Mediapart has obtained access to the screenplay. It features domestic violence, “toxic relationships”, harassment at school, a liaison between an adult and a minor, and “a case of the rape of a minor”. As with other films directed by Ruggia, this feature-length film is described in a request by its makers for funding, which Mediapart has seen, as being “partly autobiographical, strongly inspired by his adolescence”.

In Ruggia’s presentation document for the film, the characters are described as being constructed from “real memories [which] are mixed with memories that have been told, fantasised, rearranged in relation to his subconscious, his fears and his angers”.

Producer Bertrand Faivre said the first names of the lead characters were chosen as “a homage to The Devils”. He said he “froze the project, as a precaution” in July, two weeks after he learnt of this investigation by Mediapart. Faivre says he will “no longer work with Christophe Ruggia”.

On September 18th, on the day of the release in France of Céline Sciamma’s film Portrait de la jeune fille en feu (English title, Portrait of a Lady on Fire) in which Adèle Haenel stars, Ruggia posted a photo of her, taken from the film, on his Facebook account (see below). Above it he added a red heart, while according to his sister Véronique he was already aware of Haenel’s accusations against him. He did not reply to precise questions submitted to him by Mediapart about the meaning of his post. His only response to detailed questions submitted to him was a broad denial of the allegations against him which was issued by his lawyers (see the full text at the end of this article).

“Christophe Ruggia has hidden nothing,” said Céline Sciamma. “He has publicly declared his love for a child in society small talk. Some people bought his score as the rejected sweetheart, who one would feel sorry for because he had a broken heart, that he gave everything to a young girl who was reaping all of that.”

Adèle Haenel says she has now taken the measure of “the crazy strength, the doggedness” that she needed to call on as a child to resist, “because it was permanent”, and that: “What saved me was that I felt that it was not right.” She believes her social ascension in part helped her to break the silence. “Even if it is difficult to fight against the balance of power set out from early adolescence, and against the man-woman relationship of dominance, the social balance of power has been inversed,” said Haenel. “I am today socially powerful, whereas he has simply become diminished.”

Enlargement : Illustration 15

The actress sees her public stand today as a new “political commitment”, one which follows her revelation in 2014, during French cinema’s César awards ceremony (France’s equivalent of the Oscars), that she and Céline Sciamma were lovers. “In my current situation – my material comfort, the certainty of being in work, my social status – I cannot accept silence,” she said. “And if it is necessary that that sticks to me all my life, if my cinema career must end after that, so be it. My militant commitment is to assume [my situation], to say ‘Voilà, I lived through that’, and it’s not because one is a victim that one should carry shame, that one should accept the impunity of the torturers. One must show the image of them which they don’t want to see.”

Haenel said that if she is speaking out publicly today “it is not to burn Christophe Ruggia” but to “put the world back on the right track”, and “so that torturers stop strutting around and that they look at things in the face”, in order for “shame to change sides”, that “this exploitation of children, women, ceases”, and for there to be “no more possibility of double-talk”.

That view is shared by filmmaker Mona Achache, who said that Haenel’s stand was not a settling of scores nor intended “to lynch” a man but to “put to rights an abusive ancestral practice” in society. “These acts derive from the premise that normality lies in the domination of woman by man, and that the creative process permits any prolongation of this principle of domination, to the point of abuse,” said Achache.

Adèle Haenel said she hoped that making public her account of her experiences will help victims of sexual abuse. “I want to tell them that they are right to feel bad, to think that it’s not normal to suffer that, but that they are not alone and that one can survive,” said the actress. “We are not condemned to a double sentence of a victim. I don’t want to take [anxiolytic pills] Xanax, I’m doing well, I want to raise my head high.”

“I am not courageous, I am determined,” Haenel added. “To speak out is a way of saying that one survives.”

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

- The French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter and Graham Tearse