Sixteen out of 175 local children tested after the Notre-Dame cathedral fire earlier this year have a level of lead in their blood which is above the threshold at which an initial alert is triggered, according to figures released by the Paris regional health authority on Tuesday August 6th.

Two others have lead concentration levels above the threshold at which lead poisoning is officially declared, though officials say one of the cases is not linked to lead pollution from the April blaze.

The authority, the Agence Régionale de Santé (ARS), says that the healthcare of children with lead readings above the initial trigger level level must “respect the methods of the follow-up care set out by the [public health body] Haut Conseil de la Santé Publique [HCSP]”. Yet up to now the agency has not implemented medical follow-up in these cases.

Indeed, the parents of one local child with an elevated level of lead in his blood have told Mediapart of the “Kafkaesque” response of the authorities to the contamination issue.

And the need for medical monitoring and aftercare was a key demand made at a press conference held on the cathedral square on Monday August 5th. This brought together members of the lead poisoning victim's group the Association des Familles Victimes du Saturnisme (AFVS), union officials representing building and cleaning staff and Paris police officers, and Annie Thébaud-Mony, a scientist who specialises in public health questions.

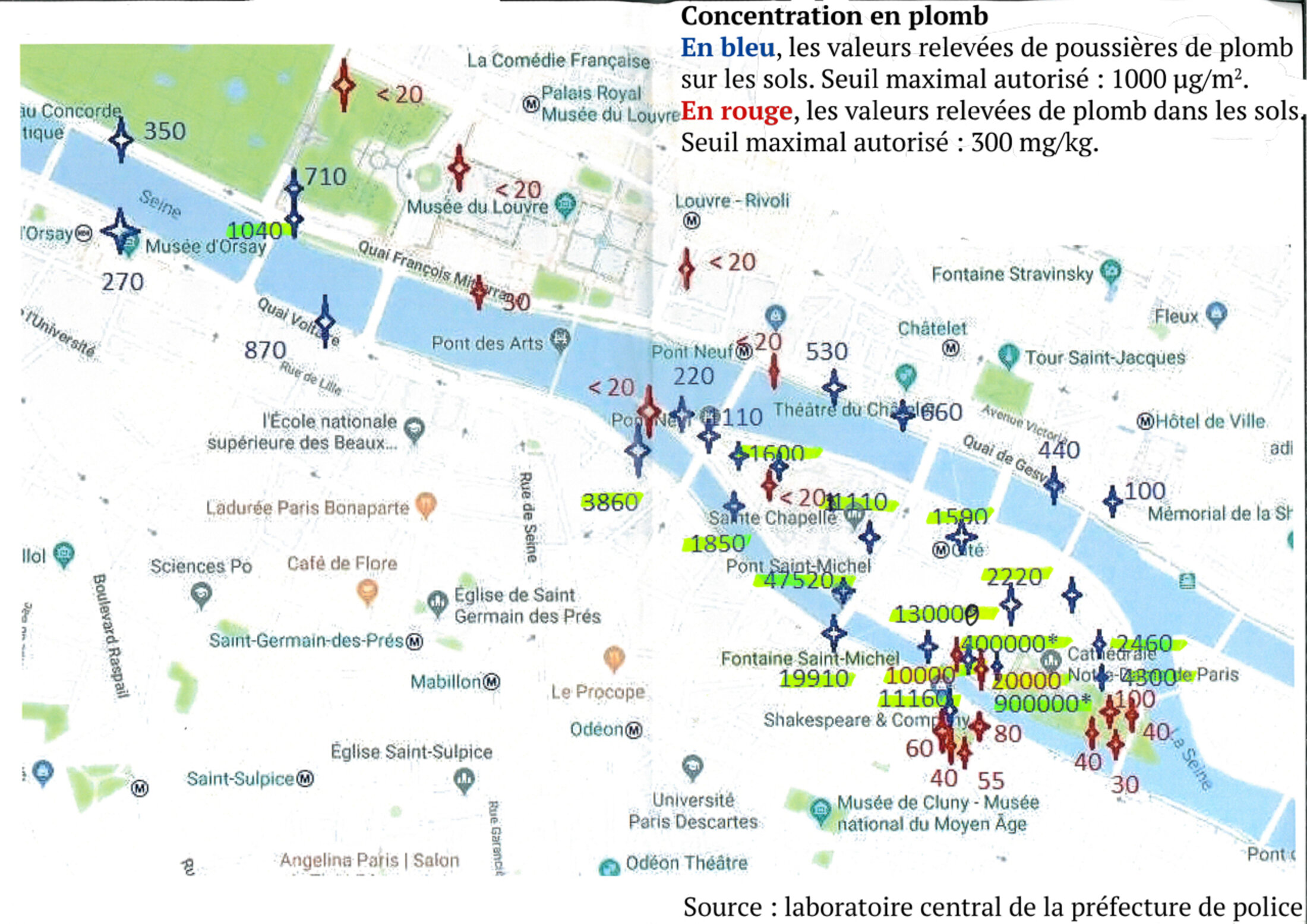

During the cathedral fire on April 15th this year close to 400 tonnes of lead was dispersed in the dust that spread over the area around Notre-Dame. The 18-month-old boy whose parents have spoken to Mediapart - and whose flat looks out onto the cathedral - has lead levels of 48.8 μg/l (meaning microgram of lead per litre of blood). This is close to the official level at which lead poisoning is declared – 50 μg/l - and well above the initial alert trigger level of 25 μg/l.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The medical research and health body the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM) told Mediapart that the 50 μg/l level was the threshold at which medical intervention must take place. “Much lower concentrations can be harmful for children,” one expert at INSERM said. “The most worrying impact of lead poisoning is a reduction in cognitive and sensory motor performance. A lead level of 12 μg/l is associated with the loss of one IQ point.” Lead poisoning can cause irreversible brain lesions and is linked with other health issues such as digestive and cardiovascular problems, cancer and fertility issues.

The regional health authority, the Paris police authority, the Ministry of Culture and City Hall in Paris have known since May 3rd about the results of the environmental lead samples taken in and around the cathedral. They waited until July18th - more than two months later- to release them.

Despite the declarations made by the health authority and by City Hall – who wanted to reassure people – the prefect or state representative for the Paris region, Michel Cadot, announced on July 25th that work at the cathedral worksite would be suspended until August 12th. The aim is to give time to repair the defective equipment that is supposed to protect workers exposed to lead.

On the same day City Hall in Paris ordered the closure of two primary schools, which were looking after around 180 children in holiday clubs. However, City Hall had earlier insisted that the results of the samples taken in the schools did not warrant “any alarm”.

Despite the risks, the health authority did not deem it necessary to launch an official campaign of screening local residents most at risk and workers to check on the level of lead contamination. Though the agency said that local residents were “encouraged” to get tested, it did not make it mandatory to have a sample taken, in particular for children.

It was not until June 7th, when a high level of lead was detected in a child's blood sample, that the health authority then “invited” families to consult their doctor or to make an appointment at the diagnostic centre at the Hôtel-Dieu hospital in Paris. During its press conference on July 18th the health authority mentioned just one case of lead poisoning, which had been found in a child aged two. But it quickly dismissed the case, stating that the lead in that instance had come not from the cathedral fire but from the balcony at the family's flat.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Meanwhile, the monitoring and follow-up care of the families potentially affected by the lead contamination has lacked any real vigour. This is highlighted by the accounts of 'Jeanne' and 'Mathieu' – at their request their real names are not being used – who are the parents of an 18-month-old child.

“The [health] authority has kept on trying to minimise the facts, without really replying to our questions,” says Mathieu, who is still distressed by the situation. The pair, aged in their thirties, have lived near Notre-Dame for the part two years. Before they moved in the standard tests carried out showed that there was no trace of lead in their home, which had been completely renovated.

On the evening of the fire the couple decided to leave the building as their windows looked out directly onto the burning building. “I was returning from the square with my son when the fire broke out,” says Jeanne. “I went home. And we left after a few hours, afraid we might be harmed by the fire. Some other homes were in fact evacuated by the police.”

They came back three days later, on April 18th, taking care to clean up any soot that had come from the fire. The couple stayed there for six days, between April 18th and May 2nd, “sometimes going to sleep with friends or with our parents”.

'You can't hide the fact that there are victims'

The young couple were alerted to the potential dangers of the lead contamination not by the authorities but by victims groups and associations which had begun to raise the issue as early as April 19th. “One of our engineer friends called us to warn us about the dangers that could be caused by 400 tonnes of lead from the cathedral roof going up in smoke,” explains Mathieu.

He and his wife bemoan the fact that none of the authorities - the regional health body, City Hall and the state – chose to warn local residents immediately about the potential risks. In a statement issued on April 27th the state prefecture simply advised residents to “clean their home… using damp wipes to remove all dust”.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

“We then began a long fight for the truth. It's Kafkaesque,” says Mathieu. “The [health authority] and the [city authorities] either don't reply to us or tell us that everything's all right, and they refused to tell us to results of the samples taken from around the cathedral.” Indeed, these results were not made public until July 18th.

On May 2nd, during a local residents meeting, the couple questioned the local mayor of the 4th arrondissement or district about the risks of exposure to lead since the fire. The mayor, Ariel Weil, told local residents their homes had to be cleaned and said he would ask the health authority to help them. “Everyone passes the buck,” says Mathieu, dismayed that he got no concrete answers. The mayor did not immediately respond to Mediapart's request for a comment, but after the initial publication of this article he got in contact to point out that during a public meeting on May 13th he had called for blood lead measurements to be carried out.

Faced with this lack of support the couple decided to get their son tested the very same day. “We had no information from City Hall or the [health authority] on the screening tests or about the measures to take. The regional health authority said they had communicated [publicly], but it all stayed confidential. Only our engineer friend and the associations raised the issue openly,” says Mathieu.

The test results for Jeanne and Mathieu's son came through on May 8th. “It was a terrible shock to learn that our child had a lead level of 48.8 μg/l, so close to lead poisoning, and which at that level required increased monitoring,” says Mathieu, who is still distraught at the news. As the worksite had not been closed off – it carried on producing lead dust – the couple then decided to move temporarily in order to protect their child.

“We had to bear the brunt of it. First of all, we urgently had to sort things out ourselves, to protect our child and leave our accommodation. We'd spoken about it with the district mayor but given his inaction we started sending letters to the regional health authority and the [state] prefecture,” says Jeanne.

They raised the issue with both authorities plus the local mayor on May 20th but got no reply.

On May 24th they asked an approved laboratory, Eurofins, to come and measure the concentrations of lead at their flat. The results were clear: in both their kitchen and their balcony there were levels of lead well above the threshold at which intervention is required.

According to a 2016 directive aimed at preventing lead poisoning in children issued by the Direction Générale de la Santé unit in France's Ministry of Health, if dust is found in homes or schools which contains lead levels “above the threshold of 70 μg/m2 [micrograms of lead per square metre] that means there is a risk of lead poisoning for any exposed children”.

At Jeanne and Mathieu's flat the concentration of lead was nearly seven times greater than that in the kitchen, at 521.5 μg/m2, while on the balcony the level was up to 689 μg/m2. In their son's room the levels were up to 70 μg/m2. “We again sent emails, on May 24th and 27th, to the regional health authority to ask what the levels of lead had been found in the surrounding area and in particular in the squares, as well as the measures that had been taken,” says Jeanne.

In their emails – seen by Mediapart – Jeanne and Mathieu warned the authorities: “Allowing the residents to think that the particles remained confined behind the unsealed barriers of the worksite is criminal. There are already some little victims, you can't hide that fact.” On May 28th the health authority finally responded to the email with the polite but formulaic reply: “We acknowledge receipt of your email.”

But the couple's “Kafkaesque” experience was not over yet. The regional health authority had already authorised the Expertam laboratory to remeasure the lead levels in the couple's flat, which was carried out on May 25th. Once again the results were well above the 70 μg/m2, with the reading in the living room, for example, reaching 307μg/m2. But the laboratory concluded there was no risk because – whether through error or deliberately – it set the threshold of any intervention at 1,000μg/m2 and not 70 μg/m2.

The latest test on the flat – which the couple have not returned to since May 2nd – was carried out at the start of August and showed that the lead levels in their child's room were down to 36μg/m2. “It's going in the right direction,” says Mathieu. “This situations is difficult financially for us because we got a loan to pay for our apartment. But our son's health takes priority and we've been fortunate in being able to get away from it.”

The health authority told Mediapart that when the intervention threshold of 70 μg/m2 is reached in people's homes it recommends that families clean the building thoroughly. But it refused to comment on the mistaken conclusion reached by the laboratory it had contracted to test Jeanne and Mathieu's flat.

On the lead screening tests, the health authority insisted that “children diagnosed with between 25 and 50 μg/l in their blood are subjected to an individual analysis by the specialist doctors from the Anti-poison and Toxicology Vigilance Centre” but did not respond to questions about the need for an official screening campaign which it has always considered unnecessary.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter