The peak of the Covid-19 epidemic earlier this year exposed the failings of France's ambulance service SAMU and potentially reduced the survival chances for some severely-ill patients, a Mediapart investigation reveals.

A series of emails, documents, witnesses and reports show that health and emergency sector experts are worried that an organisational failure worsened what was already a serious situation within the service.

The problem was particularly acute for the SAMU service covering Paris and neighbouring areas which was deluged with calls about Covid-19. This led to delays in helping patients with urgent life-threatening conditions.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

A key issue seems to have been that the system for making emergency calls did not change even as the public health situation began to deteriorate in early 2020. Whether members of the public were calling about Covid-19 or an emergency such as a potential heart attack they all used the same number – 15 – to contact the Service d'Aide Médicale Urgente or SAMU. The result was a huge bottleneck of calls. Yet still no specific number for Covid enquiries was created.

The situation also highlighted the historic rivalry between two different emergency call services in France, the ambulance service SAMU, which deals with medical emergencies, and the fire brigade, which deals with victims of fires and also road crashes and other accidents. People calling 18 for the fire brigade in France sometimes get switched to the SAMU service and vice versa.

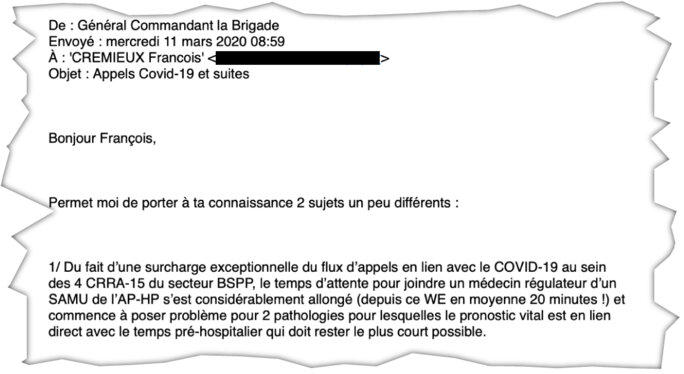

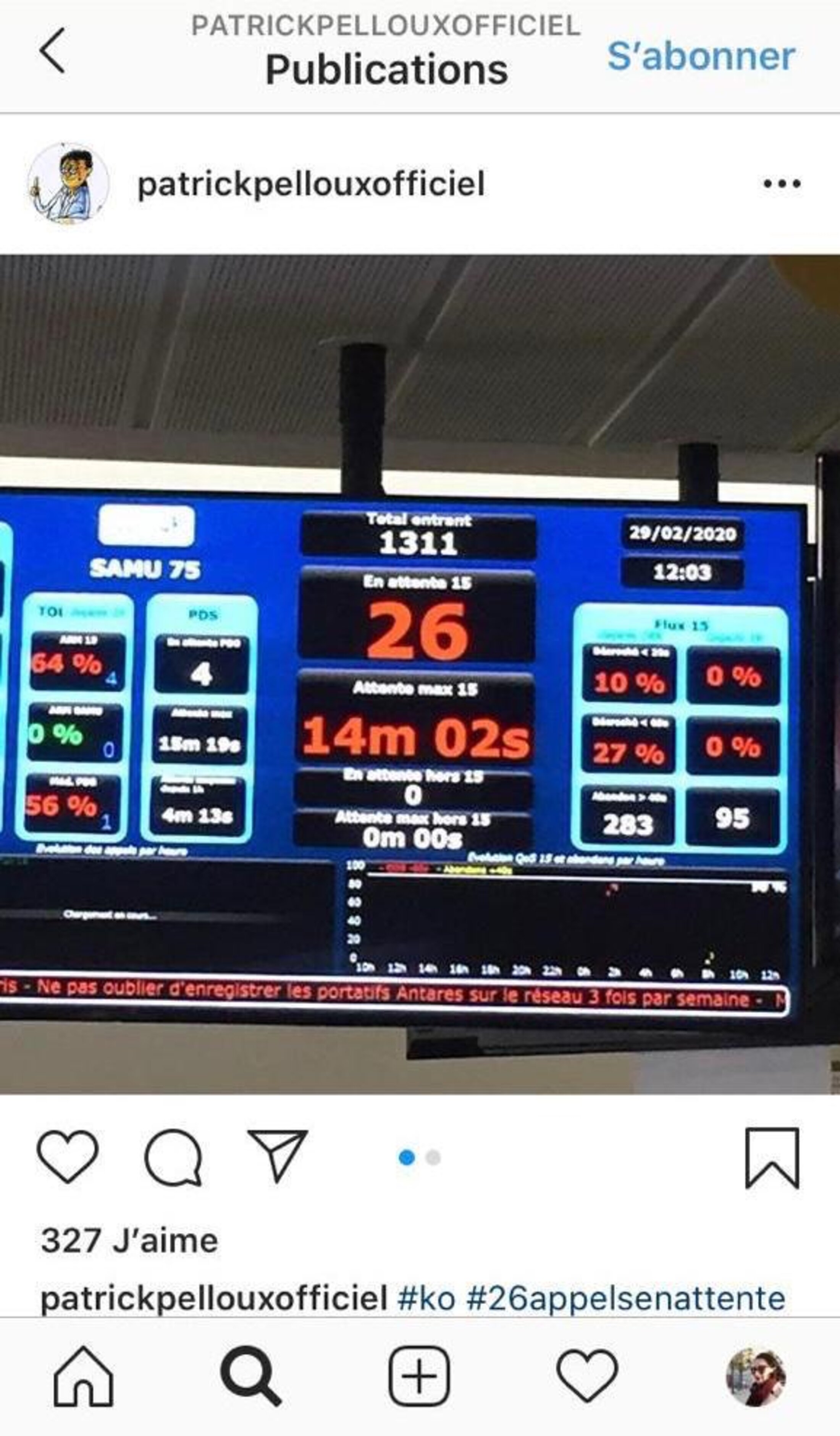

By March 11th 2020 the situation in the Paris region had become so serious that the commanding officer for the fire service in Paris, General Jean-Marie Gontier, wrote to senior management in the hospital service in Paris – to which SAMU is attached – in order to take control over certain life-critical emergencies. This is revealed in an email exchange which Mediapart has seen.

The high volume of calls to the emergency services at that time had led to two problems. The first was the time that SAMU operators were taking to answer emergency calls. The second relates to how long it took crews who arrived at the scene to get hold of a SAMU doctor whose role is to direct or dispatch them to the appropriate hospital. If this “dispatch” time is too long then it can reduce a patient's survival chances.

In one email General Gontier told François Cremieux, deputy managing director of Assistance publique – Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP), a huge hospital group in Paris: “The waiting time to get hold of a dispatch doctor at SAMU has considerably lengthened (on average 20 minutes since this weekend!).”

Enlargement : Illustration 2

In the past SAMU, which has been regularly criticised by the fire service for wanting to centralise everything, has played down such complaints, putting them down to the supposed inter-service rivalry. But the messages on March 11th, in the middle of the unfolding Covid crisis, were not about rivalry or rows but about an urgent need to save lives.

This waiting time, warned General Gontier, posed a problem in relation to two medical conditions “for which the threat to life is directly linked with the time it takes to get to hospital”. The fire chief went on to announce that “until further notice” emergency doctors at the fire service in Paris “will, without prior notice to … SAMU, direct the patients cared for in one of our intensive care ambulances with the two following conditions: serious trauma and acute coronary conditions [editor's note, conditions liable to cause a heart attack with complications such as a pulmonary oedema or even heart failure]”.

In other words, the fire chief was announcing that, for patients at risk of a heart attack and those involved in serious accidents, the brigade's doctors would dispense with the views of the SAMU dispatch doctors.

Indeed, fire service ambulances have sometimes had to wait more than 30 minutes before a SAMU doctor has directed them to a hospital. That can be a potentially fatal delay for patients with those two conditions. In the case of heart attacks, there is a risk that this will lead to heart failure. As for victims of serious traumas, a French study in 2019 suggested that a ten-minute delay in getting to hospital put up the mortality rate by 4%.

General Gontier's decision to step in came after several serious incidents that took place between May 2019 and March 2020, both before and during the Covid crisis. Mediapart has seen the reports of these incidents. Some patients or victims have since demanded to see their case notes because of delays in their cases and the impact that these delays caused.

One incident took place in the Paris region on May 3rd 2019 when a young man with a seriously injured arm had to wait for 45 minutes before SAMU directed him to a hospital. On October 5th 2019 a man in his thirties who had been stabbed had to wait 40 minutes before he was directed to a hospital. In March 2020 a patient who was showing signs of a heart attack had to wait 30 minutes. In the same month, in the height of the epidemic, the SAMU call centre in Paris “crashed three times” when a 50-year-old man urgently needed treatment for a heart and respiratory condition.

The communications office at the Paris fire service confirmed the existence of General Gontier's email but declined to make any further comment to Mediapart. Professor Pierre Carli, who is the director of SAMU in Paris and also chair of the national hospital emergency committee the Conseil National de l’Urgence Hospitalière (CNUH), also declined to comment.

However, François Crémieux, deputy managing director of the AP-HP hospital group, agreed to speak and insisted: “The email from General Gontier is evidence of the good coordination between the fire service and SAMU.” He said that the fires service could use the “dedicated line which enables fire service doctors to contact SAMU directly”. A direct line also exists between the ambulance service and the French Senate and the Élysée.

François Crémieux admitted that SAMU had been “overloaded at that time, with delays of 20 minutes. That's a rough estimate it's true, there were difficulties in accessing SAMU. The system had deteriorated a bit”. But the deputy managing director at the AP-HP hospital group pointed out that there would not be many serious trauma cases on any given night in Paris.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

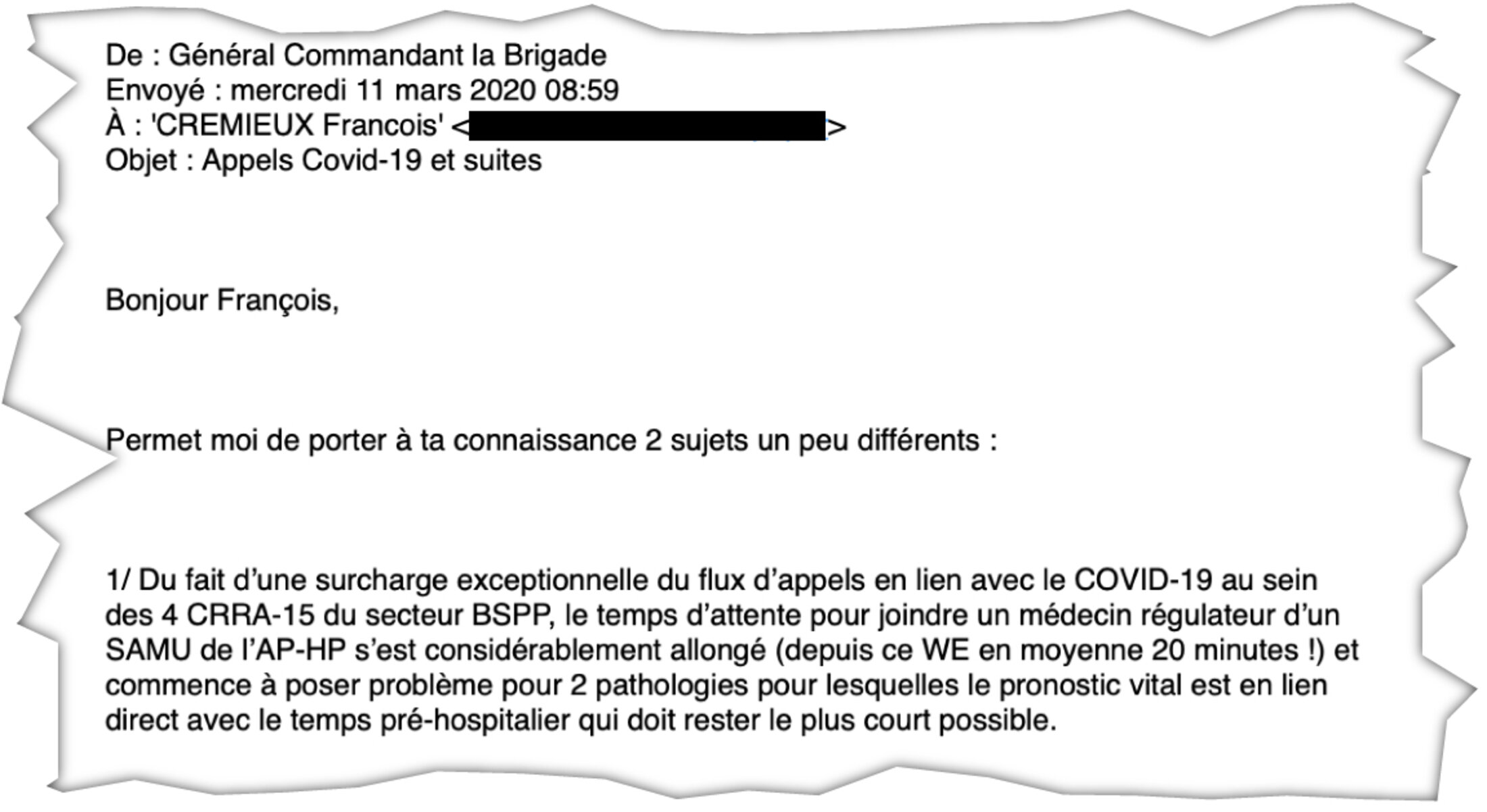

The other delay which grew massively was the time it took for operators to answer emergency calls. In theory, and according to SAMU guidelines, all calls should be answered within 60 seconds.

“The executives at SAMU, such as Pierre Carli, did not want to acknowledge the problem of delays,” said one doctor who has worked at SAMU for more than eight years, particularly in the centre where calls are handled, the Centre de Réception et de Régulation (CRRA).

The investigative weekly Le Canard Enchaîné has reported that when Emmanuel Macron visited the SAMU call dispatch centre at the Necker Hospital in Paris on March 10th 2020, one of the screens was switched off to hide the fact that the waiting time for calls was then nine minutes. “We were getting more than 6,000 calls a day compared with the 2,000 to 3,000 that we usually get at this time of year,” said François Crémieux. “This additional workload, for which SAMU wasn't prepared, was made worse to a great extent by communication errors made by the minister [editor's note, minister of health] who was then recommending people to dial 15 if they had the slightest symptom. Inevitably there were some delays but the order was given to turn off the screen. Delays remain a taboo.”

Given the situation, some SAMU staff and doctors raised the alarm, and not just in the Paris region. At Valence in south-east France Yohann Pannetier, an assistant medical dispatcher at SAMU who is also secretary of the health trade union Sud Santé, told France Bleu radio on March 14th that the service was overwhelmed by calls and in one case took eight minutes to answer a call involving a heart attack. “And in the case of a heart attack, one minute's delay in help represents a ten percent reduction in survival chances for the victim,” he told Mediapart.

“Valence was not the most affected region but we had close to three times more calls,” he continued. “We went from dealing with 300 to around 900 cases. Both in human terms and professionally you have to respond as quickly as possible, and eight minutes for a heart attack is very serious.”

'Denying the failings means refusing to improve our organisation'

A key issue is that the 15 emergency line gets busy because it attracts many different types of call. “The issue of an overload line existed before the crisis,” Yohann Pannetier told Mediapart. “There had already been some thought about the way calls were organised with, for example, the introduction of a dedicated line to provide medical advice which did not involve a life or death emergency so as to not overload the 15 emergency line.”

“The assistant medical dispatchers [editor's note, those who answer the calls] were on strike from March 2019, asking for more resources,” he said. “For example, at night in Valence there are just two assistant medical dispatchers to take the calls. How can you really expect to handle emergencies in such circumstances?”

The trade unionist said that he had asked management at the hospital what the average time was to answer the phone, and also the average time spent on the phone with callers.

“We didn't have those figures. It's a way of burying the delays and the problems of treatment,” said Yohann Pannetier. “But denying the failings in this way means refusing to improve our organisation. And inevitably that has repercussions for the patients.”

This view is not shared by everyone in the service. In the Paris region, one of the areas most affected, an emergency doctor who runs one of the SAMU services there gave Mediapart a warning. “The SAMU came through the epidemic well. These criticisms come from fire officers. Don't get manipulated.”

Yet the comments that Mediapart has collected do not come from members of the fire service. “When there's the slightest criticism, they prefer to dismiss it as attacks from fire officers,” said one doctor working for SAMU in Paris. “By hunkering down behind this 'fire service-SAMU war' they thus avoid tackling the fundamental problem, which is SAMU's failings, it has to re-think the way the emergency system is organised.”

The doctor continued: “We had to fight for nearly five years for the IT systems, boards and monitors to be put in place to show call waiting times. The boss of SAMU in Paris dragged his heels while the regional health authority supported this attempt at transparency.”

However, said the doctor, the service did not learn from its mistakes. “These organisational problems are partly linked to SAMU's desire to be at the centre of the emergency system, to centralise everything even though we can't respond to everything. And during the epidemic that had major consequences for the patients. Let's hope we take account of the explosive factors we were exposed to during the crisis.”

But there are powerful forces ranged against change. One senior professor of medicine told Mediapart that the director of SAMU in Paris intervened to stop the publication of a study on “Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest during the COVID-19 pandemic in Paris” which was eventually published in The Lancet Public Health periodical in May 2020.

The study was carried out by the Cardiology Department at the Georges Pompidou hospital in Paris and the cardiovascular research centre at the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research (INSERM), working with the fire service in Paris. SAMU was due to have taken part but withdrew.

The article noted that in the period March 14th and April 26th during lockdown the number of heart attacks in the Paris region doubled in comparison with the same period in previous years. It also stated that the survival rate fell by almost half.

Almost a third of the additional heart attacks can be directly linked to Covid-19, with confirmed or strongly suspected diagnoses.

But what about the other two thirds? Several hypotheses have been advanced by the study's authors, among them an “interruption of medical aftercare on the part of patients, because of the impossibility of being able to see a doctor or through some being afraid of getting contaminated at the hospital,” one of the authors, who asked to remain anonymous, told Mediapart.

But there was another hypothesis too. “The hospital system was overloaded and had to adapt to deal with the crisis. And it was when the issue of getting through to the emergency services was raised, whether it be SAMU or the fire service, that the former decided it would no longer take part in the study and withheld its signature. Which is regrettable,” said the author.

Not only did SAMU withhold its name from the study, it also refused to provide its data and asked for the study not to be published.

Ultimately the study was not scrapped, just modified. In an early draft, which Mediapart has seen a copy of, the hypothesis about the SAMU delays was presented in this way: “The patients calling over cardiac conditions would have had a longer wait on the telephone before getting a response from the medical emergency services (or not managed to receive a response, as was observed in several cases during the first 72 hours of the pandemic in Paris). That could have been particularly harmful, given that the majority of non-hospital heart attacks linked to acute coronary syndrome occur in the first minutes of [the syndrome's] appearance.”

This passage disappeared from the final version. This simply stated, without going into more detail, that the “response time, defined as call answer to EMS [editor's note, emergency medical services] arrival, was significantly longer”.

The doctor cited above said there was pressure over the article not just from Pierre Carli at SAMU, but also from the managing director of the AP-HP hospital group itself, Martin Hirsch.

Hirsch told Mediapart, however, that he had “not intervened in any way, either directly or indirectly, to stop the publication of such a study and I absolutely did not intervene in the process of producing this article, and I gave no instructions to anyone at all to slow down or prevent publication. On the contrary, I sought to have some data pulled together.”

However, the version of events from AP-HP's deputy managing director is different. François Crémieux said that there had indeed been interventions. “We had conversations, including with the person in charge of this study who spoke to Martin Hirsch on the telephone,” he said. “We exchanged data. We raised the question at that time as to whether the hypothesis of a delay in treatment was indeed a credible hypothesis. We concluded that the study was not sufficiently robust to put forward this hypothesis.”

François Crémieux admitted that it was possible that “there might have been an issue linked to the organisation of the care system but it has to be put in context. At the time, in April, we were in the middle of the crisis, with SAMU overloaded in all senses in terms of deployment. So we were very cautious about announcing that the issue of cardio-respiratory attacks has a link with how SAMU is organised … Today that can be stated calmly. But it wasn't rational to link them in the middle of the Covid crisis.”

In short, the focus was more on SAMU's image and public relations than on the improvement of access to treatment. Yet despite this admission, critics fear that few changes have been made ahead of the difficult days that loom ahead.

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter