Over recent years, it had become awkward, if not somewhat perilous even, to talk about Jean-Marie Le Pen with a Member of Parliament (MP) from the far-right Rassemblement National party, the former Front National which Le Pen co-founded in 1972 (alongside a French former Waffen SS officer) and which he was chairman of until 2011, when he was succeeded by his daughter, Marine Le Pen.

Those with the most admiration for the man, who died earlier this month at the age of 96, would place him firmly in the past, arguing that his outspoken racist, anti-Semitic, negationist and homophobic views were simply controversies that belonged to a bygone era. On the opposite, there are others who would insist they would never have joined a party led by Le Pen, some even claiming to have joined demonstrations in 2002 in protest at the far-right leader reaching the second and final round of that year’s presidential elections, which he lost in face of the conservative Jacques Chirac.

All that changed after Le Pen’s death on January 7th. Rassemblement National (RN) chairman, Jordan Bardella (who already in 2023 said he did not believe that Le Pen was an anti-Semite) described the latter as an “orator of the people” who had “always served France”. A number of the party’s MPs saluted a supposed visionary capacity of Le Pen, who Thomas Ménagé, MP and spokesman for the RN parliamentary group, said “had denounced before anyone else the path which France was following, and who had announced the difficulties with which it is now confronted”.

Speaking on Sud Radio, RN vice-chairman Louis Aliot, mayor of the southern town of Perpignan and the former partner of Marine Le Pen, echoed Bardella by declaring that he had “never thought” of Jean-Marie Le Pen as being an anti-Semite.

Meanwhile, in a lengthy interview with French weekly JDnews, published online on January 12th, Marine Le Pen, now the figurehead of the RN, leader of its parliamentary group and, beginning in 2012, its presidential candidate, spoke of the regret she feels at having expelled her father from the party in 2015, when it was still called the Front National.

The move, part of a strategy to “de-demonize” the party, followed his repeated negationist comments in public, arguing that the gas chambers of German death camps represented but a “detail” in the history of WWII, that “In France, the German occupation was not particularly inhumane”, and that he had “never” considered Marshal Philippe Pétain, the leader of the collaborationist Vichy regime, to be a traitor.

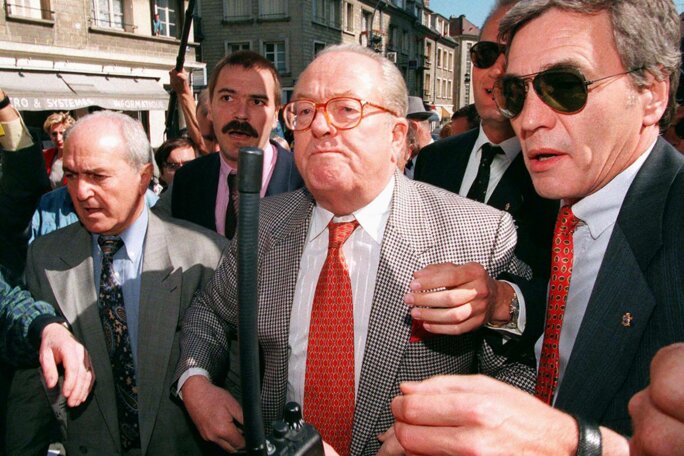

Enlargement : Illustration 1

“I will never pardon myself over that decision, because I know that it caused him immense pain,” Marine Le Pen said of her father’s exclusion from the party in her interview with JDnews, voicing regrets that can also be regarded as a confession. Now referring to her father as “Papa”, she called his anti-Semitic and negationist outbursts “provocations”, insisting that it was “a little unjust to judge him only on the basis of these controversies”. The Front National was his “baby”, which he had “created, shaped, built”, and, she said of his exclusion, “Taking that decision was one of the most difficult in my life.”

“And right up to the end of my existence I will always ask myself, ‘could I have acted differently?’” she added.

“A historical figure of the far-right, he has thus played a role in the public life of our country over close to 70 years, which is now subject to the judgement of history,” said French President Emmanuel Macron in a statement released shortly after the anouncement of Le Pen's death.

Less reserved, Macron’s recently appointed prime minister, the centre-right veteran François Bayrou, tasked with stabilising his government in France’s hung parliament, for which he depends on pleasing the RN, the largest single party in the chamber, declared on X: “Beyond the controversies which were his preferred weapon, and confrontations that were necessary on substance, Jean-Marie Le Pen represented a figure of French political life. We knew, while fighting him, what a fighter he was.”

Creating the Front National with a former Wafffen-SS officer

In 1963, after beginning a political career in the 1950s as an MP affiliated to the populist rightwing movement of Pierre Poujade, Jean-Marie Le Pen established a record-producing company, SERP, whose catalogue included WWII collaborationist speeches and nationalist hymns. It also produced a record containing songs of the Third Reich, the sleeve of which explained that Nazism was “a powerful movement of the masses, which all said was popular and democratic, which triumphed in regular electoral consultations, circumstances which are generally forgotten”. That led to Le Pen’s conviction, in 1968, for “apology of war crimes”, and which was upheld on appeal in 1971.

The following year, Le Pen co-founded the Front National. The far-right Ordre Nouveau movement wanted the new party to be a more presentable political structure through which it could unite the different elements that made up France’s rightwing extremes.

Alongside Le Pen was Roger Holeindre, a militant with the Organisation de l’Armée Sécrete (OAS), a paramilitary terrorist organisation created in 1961 to oppose Algerian independence from France, as the 1954-1962 Algerian War of Independence, in which Le Pen served in the French army, drew to a close. Holeindre created an underground network of the OAS in the north-east of the country, for which he was later arrested and jailed.

Also alongside Le Pen in 1972 was François Bigneau, a former member of the Milice (militia), a paramilitary organisation created by the Vichy regime in occupied France to fight against the Resistance movement, including through summary executions, and which participated in rounding up and deporting Jews to German death camps. A third figure completing the group was Pierre Bousquet, a former officer with the Waffen-SS “Charlemagne” division, made up mostly of French collaborators with the Nazi regime, and which was deployed on Germany’s eastern front in 1945 against the advancing Soviet army. Bousquet became the Front National’s first treasurer, while Jean-Marie Le Pen was appointed as its chairman.

Anti-Semitic and negationist

In the spirit of that group, Le Pen’s political career was marked by his frequent anti-Semitic and negationist outbursts in public, and which led to his numerous convictions for crimes related to hate speech.

In 1985, around 100,000 people gave him a triumphant reception as he took to the stage at a Front National rally in the Paris suburb of Le Bourget. It was an opportunity for Le Pen to attack four prominent Jewish journalists. “I especially dedicate your reception to Jean-François Kahn, to Jean Daniel, to Ivan Levaï, to [Jean-Pierre] Elkabbach,” he said, to ever louder jeers from the crowd as he pronounced each of their names. For that he was convicted of anti-Semitism and was barred from taking part in the programmes of radio station Europe 1, which employed the targeted journalists.

In 1987, interviewed on RTL radio, Le Pen declared that the gas chambers of the Nazi concentration camps were merely “a point of detail in the history of the Second World War”, adding that “it is not a proven truth in which everyone must believe”. That caused public uproar, and led to another conviction, this time for contesting the existence of a crime against humanity.

Yet over the following years he would reiterate the phrase “a point of detail in the history of the Second World War” several times, and notably during a December 1997 press conference in Munich with the German far-right figure Franz Schönhuber, a decorated former member of the Waffen-SS who had written a book about Le Pen. “If you take a book of a thousand pages about the Second World War, concentration camps occupy two pages and the gas chambers [occupy] ten or 15 lines, which is what is called a detail,” Le Pen said.

In 1989, interviewed by the now defunct Catholic traditionalist newspaper Présent, which was politically close to the Front National, Le Pen spoke of the role of a “Jewish international” network in the creation of “anti-national thinking”.

In 2009, Le Pen – then a Member of the European Parliament (MEP) – returned to the subject of German concentration camps. Addressing a speech to the parliament in Strasbourg, he declared: “I have simply said that the gas chambers were a detail in the history of the world war, which is obvious.” Speaking to news channel BFMTV in 2015, the year his daughter Marine organised his expulsion from the Front National, he iagain nsisted he had no regrets over the comment. “What I said corresponds with what I think, the gas chambers are a detail in the history of the war,” he said. “I maintain what I said, I believe it’s the truth and it should not shock anyone.” During that same interview he added that he challenged “anyone” to find “an anti-Semitic phrase from my political life”.

In 2011, the year Marine Le pen succeeded her father as chair of the Front National, a journalist from the broadcaster FRANCE 24 said he had been the target of anti-Semitic insults while covering the party’s congress, from which he was thrown out. “He said it was because he was Jewish that he was expelled,” commented Le Pen. “That figured neither on his press card nor, if I might dare to say, on his nose.”

In 2014, speaking on a video published on the Front National website, Le Pen made fun of showbiz stars who were publicly opposed to the far-right, including Madonna who he dubbed “Maldonna”, and suggested making a “fournée” with the Jewish singer Patrick Bruel. The word “fournée” refers to batches of bread cooked in an oven. He often appeared in the company of notorious anti-Semites Alain Soral, a far-right essayist, and the comedian Dieudonné, with whom Le Pen celebrated his 87th birthday.

In 2022, he took part, alongside the anti-Semitic essayist Hervé Ryssen, in a dinner organised by the Parti de la France, a party that claims an ideological heritage handed down from Marshal Philippe Pétain, leader of the collaborationist WWII Vichy regime.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

During the campaigning for legislative elections in 1997, Le Pen visited the Paris suburb of Mantes-la-Jolie to support his eldest daughter, Marie-Caroline, who was running there as the Front National candidate. He became involved in a brawl with leftwing militants, and physically attacked the Socialist Party candidate Annette Peulvast-Bergeal, all of which was filmed by TV crews, when he also shouted at one of the leftwingers: “I’m going to make you run, me, you’ll see, the redhead over there,” before calling him a “poofter”. In a video interview with Le Figaro in 2016, Le Pen said homosexuals were “like salt in a soup: if there’s too much, it’s undrinkable”.

Reacting to the terrorist shooting murder of a police officer, Xavier Jugelé, on the Champs-Elysée avenue in Paris in April 2017, Le Pen criticised the attention given to Jugelé’s militant campaigning against anti-homosexual prejudice within the police. “Homage was above all paid to the homosexual, rather than the policeman,” commented Le Pen.

Fiercely opposed to abortion, Le Pen declared in, 1988 that he was “Christian, so by principle against abortion”. Speaking in 1996 to the daily Le Parisien, he said that the claim “your body belongs to you is completely derisory”, adding: “It belongs to life, and also, in part, to the nation.” A few years later he explained in another interview that he did not cook because he had “a wife and a maid”, detailing that for him, a father of three daughters, “in our national and family tradition, it is the women who look after our girls, not the men”.

In 2011, as she prepared to succeed her father as leader of the Front National, Marine Le Pen referred to her heavy political heritage. “Like for the history of my country, I take all of the history of my party and I accept all of it,” she said. Fourteen years later she has expressed her regrets at expelling Jean-Marie Le Pen from the party, despite the hideous comments and outbursts that were his contribution to public debate.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

This abridged English version by Graham Tearse