Claire Marcins is a homecare worker based in the small town of Lamotte-Beuvron, situated about 50 kilometres south of Orléans in the Sologne region of north-central France. She is employed by a large national organisation that provides domestic assistance to dependent, mostly elderly, people in rural areas, the ADMR (for Aide à domicile en milieu rural), and which is now among agencies at the frontline of the healthcare crisis caused by the Covid-19 coronavirus epidemic accelerating across the country.

For while the spread of the virus is acute in large urban areas, where much media attention is focused, the threat is no less real in rural zones, where those most vulnerable in the case of infection already rely on homecare workers for their vital needs. But the service provided by the ADMR, like the parallel healthcare services in general, faces heightened difficulties of staff shortages due to the crisis, not least because numerous homecare workers are mothers who, following the indefinite closure of all educational establishments this week, have children to look after at home.

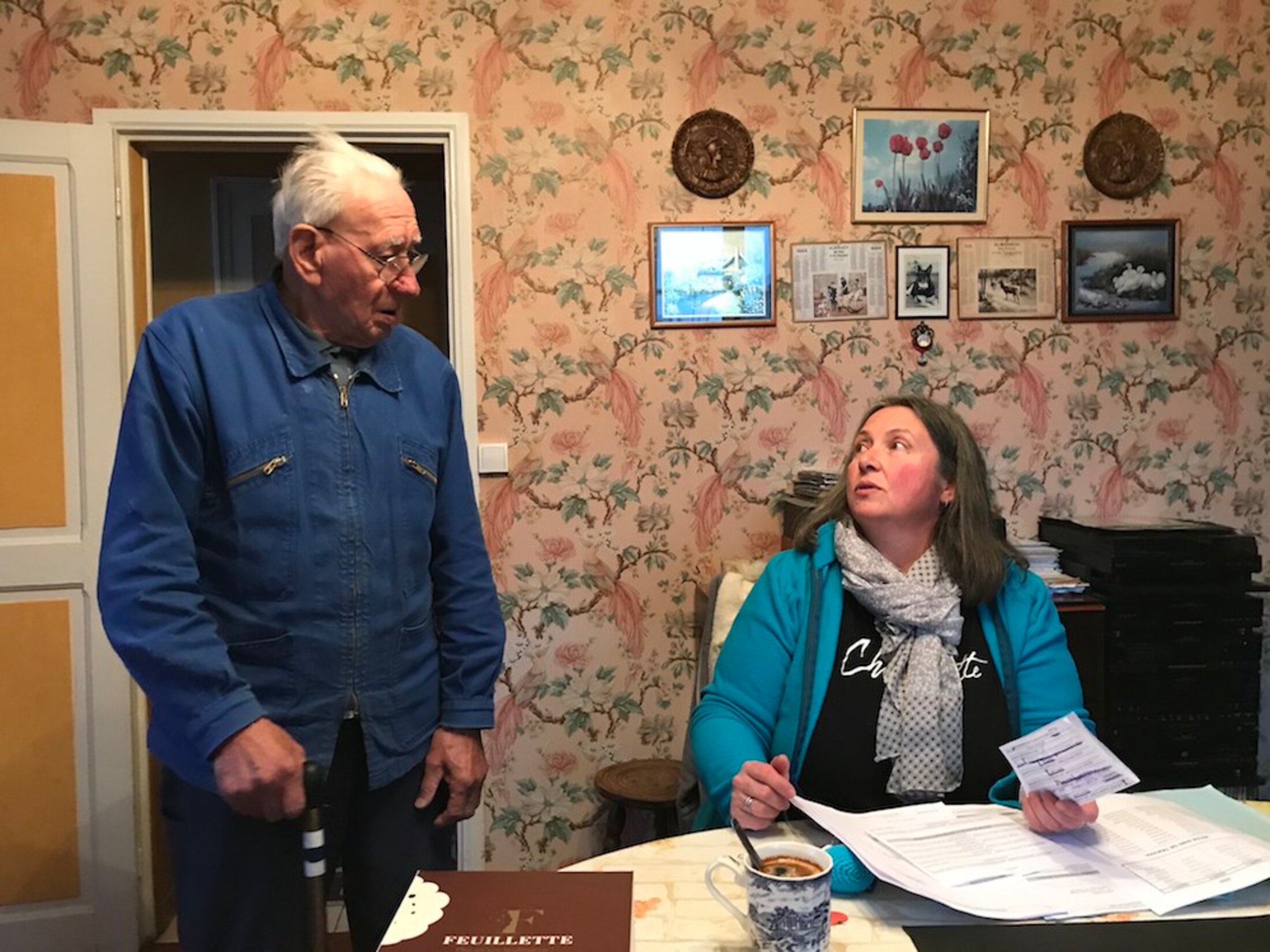

Claire Marcins, in her fifties, is not one of them, and as a result she will be required to up her workload to fill in for others, and also to scale down those visits that are not considered to be a priority. One example of these is attending to Armand Jarry, a widowed former truck driver in his nineties. She normally sees him once a week, and which includes spending a couple of hours playing with him at Triominos, a board game variant of dominoes, to help stimulate his memory.

“But just now he’s recently left hospital,” she said. “They put him on a course of re-education at the Institut de Sologne [clinic] and he can no longer be visited by me.” Contact by outside visitors with the elderly in care, notably in establishments catering for the dependent, known as EHPADs, is now banned. “The nurses attend to his every need, I have every confidence in them, but it’s very hard for him.”

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Marcins, like others interviewed here, was speaking to Mediapart just days before the draconian shutdown measures were announced by French President Emmanuel Macron on Monday evening. She is particularly worried about the threat of the virus on two of those she attends to; a mother paralysed from the waist down after a car accident and Hélène, a 36-year-old former nurse with multiple sclerosis who lives in an isolated village. The paralysed mother has no properly working abdominal muscles. “She already has difficulty breathing, so it would be very difficult if the coronavirus reaches her,” said Marcins. As for Hélène, she has already prepared her last wishes. “Thursday evening, she looked me straight in the eyes. She says she is ready to pass on, and refuses to be intubated if the need arose.”

The homecare worker holds onto the hope that neither would be infected by the virus. “Around here, the care workers are a little old, they don’t all have children to look after, so they’ll mostly remain mobilised, she said. “Also, we’ve already experienced periods of heatwave and strong flu without too much damage. If required, I’ll work a supplementary one weekend out of two, rather than one weekend out of four. We’re used to meeting situations, it’s our job.” Luckily, at the beginning of the winter she received a small stock of masks – an essential item but which French healthcare workers and doctors are currently suffering from a shortage of.

Contacted by Mediapart, the head of the regional branch of the ADMR in the surrounding Loir-et-Cher département (the equivalent of a county) declined to publicly comment on how it is coping with the developing major health crisis. But speaking on condition of anonymity, some of those in charge of the local offices around the Loir-et-Cher spoke of their concerns. “This Friday was very heavy in terms of organisation,” said one. “We might find ourselves in a panic in eight days’ time, when the provisional solutions for the work roster will be used up, and when our young staff will have to stay at home.”

“We expect then having to extend the time between visits, to choose between visits,” she added. “But nevertheless, we won’t stop delivering meals.”

Another explained: “A lady who felt weak asked her homecare worker not to come anymore to do the housework. Other beneficiaries [of the homecare services] wrongly believe they are a burden, and suggest to their carers that they stay at home to look after their [own] families. I have one employee, a mother of three, who has taken holiday leave because there was no other solution. And amid all that, we still don’t have disinfectant gel.” Supplies of handwash disinfectant gel quickly dried up in France last month as the coronavirus crisis began in earnest, prompting the government to allow high street chemist’s shops to make their own, but there then followed a shortage of containers to put the solutions into.

In the neighbouring Indre-et-Loire département, the closure of the universities in the town of Tours – as part of the nationwide closure of educational establishments – may prove to be a boost for the ADMR amid the acute problem of staffing shortages. “A lot of students are coming forward to give us a hand, and that’s unexpected,” said Laure Blanc, in charge of the ADMR branch in the département. “They’ll be able to make a little bit of money and it should provide us with some relief, especially at weekends.” She is in charge of 43 local offices, with a payroll of 1,200 homecare workers who attend to the needs of around 6,500 dependent people. “Some worried families want to see fewer visits. We are not healthcare workers, not all of it is vital, so we don’t impose anything, but we need to make sure that it [making fewer visits] remains marginal. For the moment, I’d say that we’re managing the situation like during the period of major strikes,” she explained, referring to the months of crippling, rolling strikes last December and earlier this year, notably affecting the transport sector, held in opposition to the government’s pension reform plans.

Meanwhile, those volunteers who provide a part of the ADMR services, such as organising courses on teaching the elderly how best to avoid accidental falls, or taking them on excursions, have cancelled their activities in order to be on standby help for the homecare workers. “They will be available when there’s a snag with a vehicle, a logistical problem,” she added. “We have a wonderful opportunity to mobilise solidarity.”

One of those who benefits locally from the services of the ADMR is an 83-year-old lady who lives close to the town of Blois. She receives help at home where she struggles to look after her husband, victim of a fall and who stays confined within the house, fearful of returning to hospital. The coronavirus epidemic has changed their routine. Madame Richefort began by doing her shopping earlier than usual in order to avoid crowds of shoppers, before finally asking her niece to take over. Her dread of the dangers is such that she asked her homecare helper to stop visiting. There was no question for her of taking part in last Sunday’s local elections, which were controversially held in contradiction with French government advice to the population to restrict movements and physical contact – advice which became an order on Monday evening as the country went into an official lockdown. “I think we are now very afraid of all that, you understand,” said the elderly lady, speaking to Mediapart by phone.

-------------------------

- The French version of this report can be found here.