One of President François Hollande's top advisors quit his job on Friday just a day after Mediapart revealed that he had been involved in a potential conflict of interest while working as a senior government inspector.

Aquilino Morelle, the president’s special advisor, has strongly denied the claims that he had not declared his private work with a Danish drugs company while working as an inspector for the French state's elite public service inspectorate, the Inspection générale des affaires sociales, (IGAS). But Morelle stepped down after IGAS publicly confirmed that they have no record of him being given authorisation to carry out the consultancy work in 2007.

Already on Friday morning, his days looked numbered at the Elysée when the new first secretary of the ruling Socialist Party, Jean-Christophe Cambadélis, told i-Télé news channel that if the revelations about the pharmaceutical industry links and conflict of interest were “verified” then: “I don't see how he can stay.” Once IGAS then confirmed Mediapart's revelations, Morelle quit his post as a high-profile advisor to the president. Announcing his decision, Morelle still insisted that he had done nothing wrong. “I have never been in a situation of a conflict of interest,” he said. But he said he wanted to “put an end to his duties to be fully free to respond to the attacks”.

Reacting publicly to the resignation, which he said he had “immediately” accepted, President Hollande said: “Aquilino Morelle took the only decision possible, the only appropriate decision, the only decision that will allow him to respond to the questions that have been put to him.”

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Mediapart led a six-week investigation into the activities of Morelle, the man who was once speech writer to socialist prime minister Lionel Jospin, a former doctor who went to France's select finishing school for senior public servants and politicians, the son of Spanish immigrants and who is often portrayed as a “son of the people” who embodies the left-wing in power.

What Mediapart discovered about Aquilino Morelle is significantly more serious than the gossip that surrounds him regarding his alleged megalomaniac behaviour and a taste for breaking convention, who strutted around the Elysée in a manner that one source described as a “petit marquis” ("little lord"). Instead, Mediapart's investigations have revealed that this now former advisor, who only once stepped into the public limelight when, as an inspector for IGAS, he wrote a high-profile report on the Mediator drugs scandal, has both lied and omitted details about himself.

After leaving the elite École Nationale d'Administration (ÉNA) graduate school in 1992, Morelle joined IGAS, a prestigious and powerful body which describes itself as the “inter-ministerial audit and evaluation office for social and health, employment and labour policies”. Since then he has moved between the offices of government ministers and private firms, and in 2007 he returned to IGAS. It was the, in the same year, that he was a co-author of a report entitled 'The framework for care programmes for patients involved with drug-related treatment, financed by pharmaceutical companies'.

But at the same time Aquilino Morelle was working for Lundbeck, a Danish pharmaceutical laboratory. A senior executive of that firm at the time says: “He was recommended to us by a professor at the [Paris public health authority] AP-HP[Assistance publique – Hôpitaux de Paris]. His profile was very interesting. We met. He told me that he was looking to work in the pharmaceutical industry, that he had free time, that his work at the IGAS only took up two out of five days, which seemed strange to me. But his profile and his contacts book interested us.”

So Morelle, an IGAS inspector, organised two meetings for the laboratory with members of the state health product organisation, the CEPS (Comité économique des produits de santé), which fixes the price of medicines and also the rate at which they are reimbursed to patients by the state's social security system. “He opened doors for us,” says the executive. “And that is a major issue; allowing us to go and defend our case with the right person. We were looking to stabilise the price of an antidepressant, Seroplex.”

However, the executive did not ask Aquilino Morelle to go with them to the meetings. “I thought that could have been counter-productive. He was in such a complicated position, so unethical, that it could have had a doubled-edged effect. Normally it's usually retired people who carry out this sort of activity.”

Questioned by Mediapart before the original article was published, Aquilino Morelle only answered questions by email, and postponing planned meetings. Having been paid 12,500 euros - plus tax - for this service, he insisted that everything was done within the rules because “as a civil servant a certain number of additional activities are authorised, including teaching and giving advice”. Had he declared this contract to the civil service? “These activities had to be declared to the IGAS. I have no found a trace of this despite my searches” he wrote to Mediapart. “These are old events from seven years ago, and unremarkable.”

When IGAS was asked about this work for a private laboratory, it initially told Mediapart that “article 25 of the law of July 13th 1983 allows public servants to carry out certain additional activities. In this capacity, assessments, consultation, literary and scientific activities and teaching can be authorised by the head of the service. This was what was done in 2007.”

Mediapart then tracked down the head of service – the director – of IGAS at the time, André Nutte, who is today retired. “To be honest I have a good memory,” he explained to Mediapart, having been able to cite immediately the different reports that had been written by Aquilino Morelle at the time. “But I don't remember having signed such an authorisation. If IGAS has such a document, let them produce it. We'll quickly see who signed it. Because it doesn't make sense. It's like granting the right to a hospital doctor who has joined the IGAS to go and work at the same time in a private clinic. Or to a workplace inspector to advise a business.”

Mediapart reported André Nutte's comments to IGAS, which on April 16th changed its response. In fact, it then said, the authorisation in 2007 was only the permission to to give lectures at Paris 1 University (the Sorbonne). No other authorisation has been found, they said.

Indeed, according to Michel Lucas, who was head of IGAS from 1982 to 1993, allowing such a combination of work would simply have been wrong. “These two functions are incompatible. You never allow an inspector to work for a private firm. So, a private laboratory...” Whatever, Article 25 of the 1983 law cited by IGAS is quite clear: “Civil servants and non-permanent public staff devote all their professional activity to the tasks that have been conferred on them. They cannot in a professional capacity carry out paid-for private activities, of any nature whatsoever.” Unless specific permission has been granted “the violation [of this rule] leads to the repayment of the sums wrongly received, with the money being deducted from salary”.

Moreover, under Article 432-12 of the criminal code such double activity could be construed as an illegal conflict of interest. At the time these events occurred, in 2007, this was punishable by a five-year prison sentence and a fine of 75,000 euros.

An advocate of transparency...for other people

The money that Aquilino Morelle earned for these activities was put into a company called EURL Morelle, which he established in 2006, and which was formally wound down in March 2013. However this firm's accounts were never formally lodged at the commercial court, as they are required to be under the law. On February 28th 2007, the very day that he rejoined IGAS, Aquilino Morelle, who was the only shareholder in his company, resigned from his role as director of the firm and replaced himself with his younger brother Paul.

The profile of Paul Morelle, who in 2009 went on to open a flower, wine and chocolate store in Paris's 15th arrondissement (district), does not at first glance seem consistent with that of an expert in medicines. However, the change of management at the company did mean that from then on there was no company directly linked with the name of Aquilino Morelle.

Aquilino Morelle has never referred to his work for the pharmaceutical industry. “Absolutely no rule stipulates that I must 'account for' these contracts,” he said in an email to Mediapart. Yet it was Aquilino Morelle who, at the time of his report into the Mediator affair, which involved claims that the drugs company had urged doctors to prescribe the pills at the heart of the scandal, was in TV studios and on the radio calling for greater transparency in the medical world.

He said on radio station France Info on June 24th 2011: “Everyone [must be] straight with themselves and with others. There is no ban on a doctor having a relationship with the pharmaceutical industry. One can understand that. What must happen is that it should be made public. These contacts must be public. When you publish your relationships you're transparent and anyone can look to see...if there is anything that might pose a problem in terms of independence. That's all it is – but it's huge. [If] one has a relationship with the pharmaceutical industry, everyone must know about it. We're arriving at situations where the experts have become involved. Judge and jury. We have to end that.”

And during an online chat with Metronews, Morelle neatly summed up his argument as: “Yes, it is true that the pharmaceutical industry has a strong influence on current medicines policy...The prevailing view is that the pharmaceutical laboratories have a kind of 'right' to market their products, as if it involved 'goods' like any others....we must change this.”

One participant asked: “Can you give the names of the laboratories who carry out the most lobbying of men/women politicians?” To which Aquilino Morelle replied: “The whole pharmaceutical industry is involved.”

But Morelle's previous actions showed that he was far from being against the pharmaceutical industry itself. For after the Danish firm Lundbeck ended its relationship with him in December 2007, Morelle continued to try to work in the industry in 2008 and 2009. A senior executive at leading French drugs firm Sanofi told Mediapart he had agreed to meet with Morelle. And Servier, the company whom he later demolished in the Mediator drug report, and whose boss Jacques Servier died on April 16th, also told Mediapart they received an application from him to serve the company at this time. It should be noted that this was before the Mediator health scandal broke. Yet within the industry, Servier's reputation, its systematic use of young female sales representatives, and its in-depth research on the political affiliations of its future employees, were already widely known.

At the time, in the opinion of various laboratories who received his application, Aquilino was looking for full-time work. Or more precisely pay to support his political career, rather than a real job. This did not interest the pharmaceutical laboratories and Morelle failed to find a position.

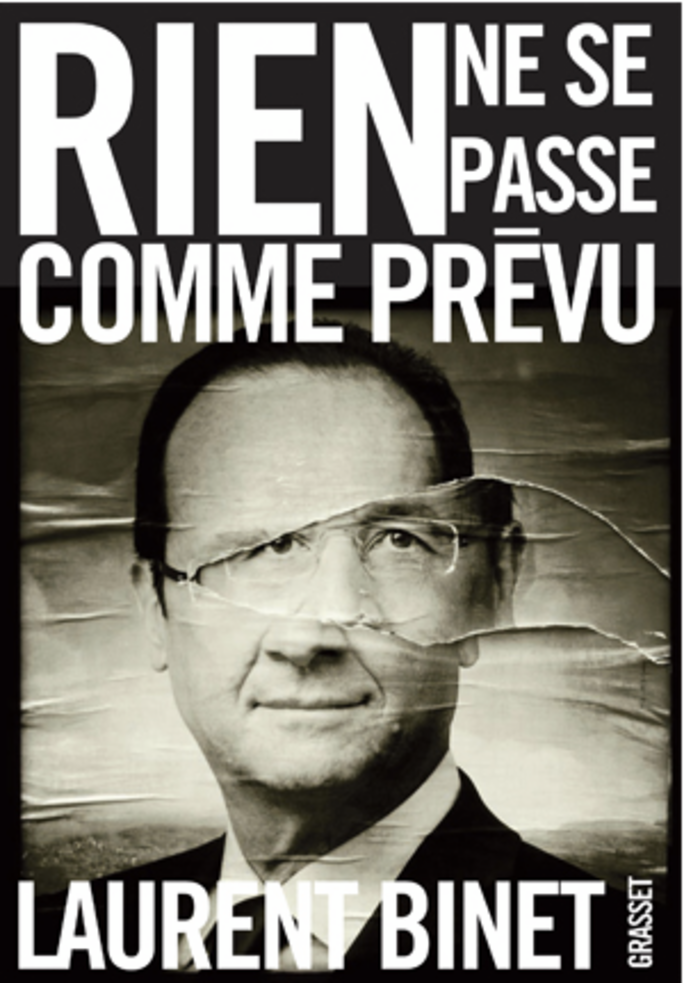

However, this had not been Aquilino Morelle's first contact with the industry. As stated earlier, he had left the ENA in 1992, though he did not graduate as second in his year, contrary to what he told writer Laurent Binet in 2012 in the latter's book Rien ne se passe comme prevu ('Nothing goes as expected'), a behind-the-scenes look at the Hollande presidential campaign (see below, right). Instead he was 26th. Nonetheless, during his oral examination at ENA he was spotted by future finance minister Pierre Moscovici and quite soon he joined the ministerial office of then health minister Bernard Kouchner.

Here Morelle occupied the post of technical adviser in charge of medicines, though Mediapart has not been able to find a record of this in his biographical details. This was the same position held two years previously by Jérôme Cahuzac, who in 2012 would become budget minister before resigning and later admitting he had an undeclared, tax-evasing foreign bank account. The role is such a pivotal one that in the space of just a few months it gives the occupant a comprehensive contacts book of connections in the pharmaceutical world.

After the Left's defeat in the Parliamentary elections of 1993, Aquilino Morelle rejoined the IGAS, where he is remembered with some ambivalence. Twenty years on, some inspectors still speak of the way in which he made use of a collective assignment and report on blood donations in the prison system to provide material for his own book on France's notorious contaminated blood scandal, La Défaite de la sante publique ('The Defeat of Public Health') which helped make his name. At the time he was not regarded as lazy, but as someone who dabbled in everything, and who as a result had a tendency to be slapdash in his work as an inspector.

In 2002, having worked with outgoing socialist prime minister Lionel Jospin for five years, he returned to his role in the IGAS without consultation. His own political ambitions were in ruins; he had failed in attempts to win a seat in local elections at Nontron in the Dordogne in south-west France 2001, and in parliamenteray elections in theVosges region in eastern France in 2002 (he later again failed in a parliamentary constituency in the Seine-Maritime in north-western France in 2007).

That sampe year, Stéphane Fouks, the boss of public relations firm Euro RSCG – now known as Havas Worldwide – offered him a way out, with the blessing of the ethics committe that oversees the moving of public servants into the private sector.

However, at Euro RSCG Aquilino Morelle quickly found himself back dealing with the pharmaceutical industry. Working in marketing in the agency’s healthcare division on the corporate side, he was asked to work on the public image of laboratories, to advise on communication strategies and to reflect on a way of improving the image of medicines with both consumers and doctors. At the time Euro ESCG's principal clients in this sector were Pfizer, Lilly, Aventis and Sanofi. But apparently his work was not what the agency expected. According to former colleagues, he was seen as protective of his contacts, not a hard worker and not very good at commercial relationships.

The IGAS inspector then decided to use his contacts for his own benefit. While working alongside former socialist prime minister and France's current foreign minister, Laurent Fabius, for a 'no' vote in the 2005 referendum on a European constitution, and while carrying out some undemanding work at the biotech industry centre Génopôle at Évry, south-west of Paris, and the biomedical engineering centre Medicen in Paris, he set up the company EURL Morelle. It was at this time that the American pharmaceutical firm Eli Lilly paid him 50,000 euros (in three payments of 12,500 euros plus tax), essentially to organise lunches in plush restaurants in Paris's 8th arrondissement.

A senior Eli Lilly executive from the time recalls: “He got me to meet parliamentarians of the Left such as Marisol Touraine [today the minister for social affairs], Jean-Marioe Le Guen [today junior minister in charge of relations between the government and Parliament] and Jérôme Cahuzac. As well as journalists.” People who are all aware that Aquilino Morelle has worked for the pharmaceutical industry.

“He was involved in normal lobbying work,” recalls the senior executive. “He supported me in my views – of course we paid him for it - on the role of generic medicines, on employment, on the role for making new innovative medicines. As an administrator at the LEEM [the drug manufacturers' body Les Enterprises du Médicament] I held the standard views. And he, an intellectual, cultivated, good at meeting people, knew what to do to support that.” At Mediapart's request, Lilly dug out of its archives the title of the job contract with Morelle: “The role of analysis and advising on Lilly's image, and preparation of its crisis communications.”

'They are just malicious rumours'

During the course of its investigation Mediapart spoke to a wide number of people who work at the French presidential office, the Elysée Palace. Care was taken to cross check and verify each piece of information, especially given that with the recent changes in power groups at the Elysée there is always a risk of scores being settled. Moreover, the communications department there had already started to put out the message that stories concerning Aquilino Morelle at the Elysée “are just malicious rumours”.

Mediapart was not able to ask him precise questions on these issues. However, aware that this website wanted to speak to speak to him about alleged abuses, he himself spoke in an email of “completely unfounded claims, which are simply aimed at sullying [my name]. In political life certain people sometimes have an interest in casting suspicion on another.”

Naturally, for certain people Aquilino Morelle's love of luxury might be surprising. But that does not mean he is doing anything wrong. Morelle always underlines his modest background, his large Spanish immigrant family, his mother who spoke French poorly, of how his father was a tool grinder at car-maker Citroën. It is possible to be wealthy, to spend a lot of time in Florida, to consider that “what's hard is to see the workers cry”, and still be “fundamentally of the Left”, as he told Les Échos newspaper.

Following the Cahuzac affair, ministers were required to make a declaration of their capital assets. At the time the “son of the people ... who will never forget where he comes from” - as Morelle was described in the Journal du Dimanche – sent ministers a comment article he had written for Libération in July 2010, entitled 'Can a man of the Left be rich?'. In it he developed the idea that “the sincerity of a commitment or the force of a conviction cannot be measured simply by the yardstick of a bank account”.

No one denies this, neither the Elysée nor elsewhere. But what does concern people at the presidential office, questioned in the preaparation of this article, are his shocking manners; the way in which Morelle addressed junior staff, used them, frightened them, and the many abuses of his function. Aquilino ensured that his two drivers were not part of the drivers' pool at the Elysée. They were therefore made available for him, and those close to him. One example is that, at the end of Tuesday afternoons – as Mediapart has been able to verify – one of his two drivers would drive his son to take part in personal activities in the city's 15th arrondissement.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Morelle also used his secretaries to deal with his personal matters, for example when he had a problem with one of the many tenants of his properties. According to Mediapart's research in different land registries in France, Morelle, who lives in Paris's 5th arrondissement, the Latin Quarter, owns properties in Paris, Saint-Denis north of Paris, Sarlat and Périgueux in the Dordogne in south-west France and Perpignan in the south of France. Most of them were bought jointly with his wife, who is chief-of-staff at the ministry of culture.

Hollande's political advisor had been hard at work since January. Up until that point Morelle did not have a reputation as a hard worker. In May 2013, during a screening at the Elysée of the documentary 'Le Pouvoir' ('Government') by Patrick Rotman, which depicts everyday life at the Palace, a large number of presidential office staff were present. In the middle of the film there is a scene which shows Morelle arriving at the Elysée and climbing the steps to his office. In the audience a voice called out: “Oh! It's 11 o'clock!”, which was greeted with general laughter.

Throughout 2012 Aquilino Morelle attributed speeches written by the former speech writer Paul Benard to himself, amid relations that quickly became tense. Made aware of the situation, Hollande removed the writer from the clutches of his political advisor in December 2012.

Often Hollande's special advisor on politics was absent, and no one knew where he had gone. At the baths in the Marais district of Paris, Mediapart was told that at one time Morelle came “not every Friday but very often in fact, in the middle of the afternoon. For a sauna, a Turkish bath, a scrub, sometimes a massage”. At other times he indulged in martial arts. Morelle has a talent for the martial arts, and has ocassionally been presented as a multiple French champion at karaté. In fact, according to the French karate federation, he has never been a national champion or finalist, not even in junior categories.

Morelle was also careful about his appearance – and keeping his shoes clean. David Ysebaert first polished Aquilino Morelle's shoes at the Bon Marché department store in Paris's upmarket 7th arrondissement. The shoe-shine gave Morelle his card, and a few weeks later “a woman, probably his secretary, called me to fix an appointment”, says Ysebaert. At the Elysée Palace itself, no less. And then about every two months thereafter “the length of time that a good glazing should last”, the shoe-shine returned to the presidential Palace to look after the shoes of President Hollande's special advisor. “Aquilino Morelle has 30 pairs of luxury shoes, hand-made to fit his foot which has a particular shape. Davisons, Westons...leather shoes always of the same style,” says Ysebaert.

On two occasions, says the shoe-shine, Aquilino Morelle even took over the main reception room in the Hôtel Marigny – a town house near the Palace used by state visitors – so that he could have his shoes shined all alone in the middle of this gilded room. This corroborates information that Mediapart had received from a source inside the Elysée. “Apparently there was an emergency,” recalls David Ysebaert. “He was on the phone in his socks, in the middle of this immense room. And I was opposite him in the process of polishing his shoes.”

This episode, which took place in March 2013, became the subject of much talk in the corridors of the Elysée. It sits awkwardly with the image of modesty and normality that President Hollande said he wanted to be the hallmarks of his presidency. But at the Elysée itself few people are said to be surprised any more by the behaviour of a man who, since the arrival of his friend Manuel Valls as prime minister and the removal of his enemy Pierre-René Lemas as secretary general of the Elysée, had become a dominnat figure in the presidential office.

Yet Aquilino Morelle's duties as a special advisor also seemed to leave him free for parallel professional activities, for he occupies a position as a part-time teacher at the Sorbonne in Paris, working equivalent to “96 hours a year”, says the university. Nominated for the first time in 2003, his position was renewed in 2012, as has already been reported. He teaches in three areas; health service regulations, major contemporary problems and a general culture course preparing students for the ENA entrance exams. All this earns him an additional salary of 2,000 euros a month.

The president was already alerted to some of his advisor's behaviour. During the first year of Hollande's presidency the message was passed to Morelle to stop ordering up some of the best vintage wines from the Elysée cellars for simple lunches or work meetings, some of them with journalists. This practice went down badly with government cabinet ministers who say they pay 8 euros for their working lunches. A few weeks later Hollande decided to limit the consumption of the best vintages, and to sell a part of the Elysée's wine stock.

Some also complain that during foreign trips at the start of the presidency Morelle was overly fond of swimming pools during the day and luxury rooms at night. And when he first arrived in his office, which is next to that of the president, Morelle asked for several decorative works to be carried out, and changed furniture several times.

In April 2013, after the Cahuzac affair which showed the latter's close relationship with the pharmaceutical industry, a succession of incidents at the Elysée suggested that perhaps Morelle's time was up. For several months he was sidelined, and no longer went on foreign trips with the president or took part in some key meetings. But François Hollande did not take the decision to get rid of him. Instead, by the autumn of 2013, and after several PR failures at the Elysée, his fortunes changed.

He came back into grace in particular at the time that the president’s affair with actress Julie Gayet was revealed in January this year, and he was promoted. It was Morelle who was behind the rapprochement between two key figures in the government, Arnaud Montebourg, now minister for the economy, and Manuel Valls. It was Morelle who endlessly pushed for Valls to replace Jean-Marc Ayrault as prime minister, which finally took place on March 31st, 2014. By the middle of April, Morelle occupied a central role at the Elysée.

Immediately after its publication, Aquilino Morelle was quick to react to the Mediapart story on his Facebook page and denied any wrongdoing. In particular he denied any conflict of interest by carrying out work for the Danish pharmaceutical firm Lundbeck while working as an inspector for the IGAS, and insists that he did declare the work to the inspectorate. “These activities had to be declared to the IGAS. I have not found a record of this despite my searches. These are events from the past – more than seven years ago.”

Morelle denied having any contact with this company before or since. “In particular when I was designated by the head of the IGAS to coordinate the investigation into Mediator in November 2010, I had absolutely no link with any company whatsoever, and in particular absolutely no link with any pharmaceutical laboratory.” Morelle also denies any suggestion of hypocrisy over his call for openness about links with the pharmaceutical industry. “The remarks attributed to me about health experts were in a precise context: that of relations between medical experts working in health safety agencies....and the pharmaceutical industry. They underlined a precise context: that of the seriousness of the faults committed in a public health scandal [editor’s note, the Mediator affair ] that, according to the available estimates, caused around 2,500 deaths...”

On his use of chauffeurs and secretarial staff for personal matters Morelle said: “It is true that my extremely heavy work schedule has not always allowed me to go myself and pick up my son on Monday evening, at 7.30pm, after he has left a class – something which I would love to have been able to do myself. It is the same for certain personal questions, that my secretariat has kindly suggested taking off my hands, on an ad hoc basis.”

------------------------------------------------------

English version by Michael Streeter