The coming winter promises to be tough for France’s glass-making industry, and for the smaller companies in particular. Glass-making firms are major energy consumers and, unlike in many other industries, the equipment that guzzles that energy cannot be easily switched off, even for brief periods.

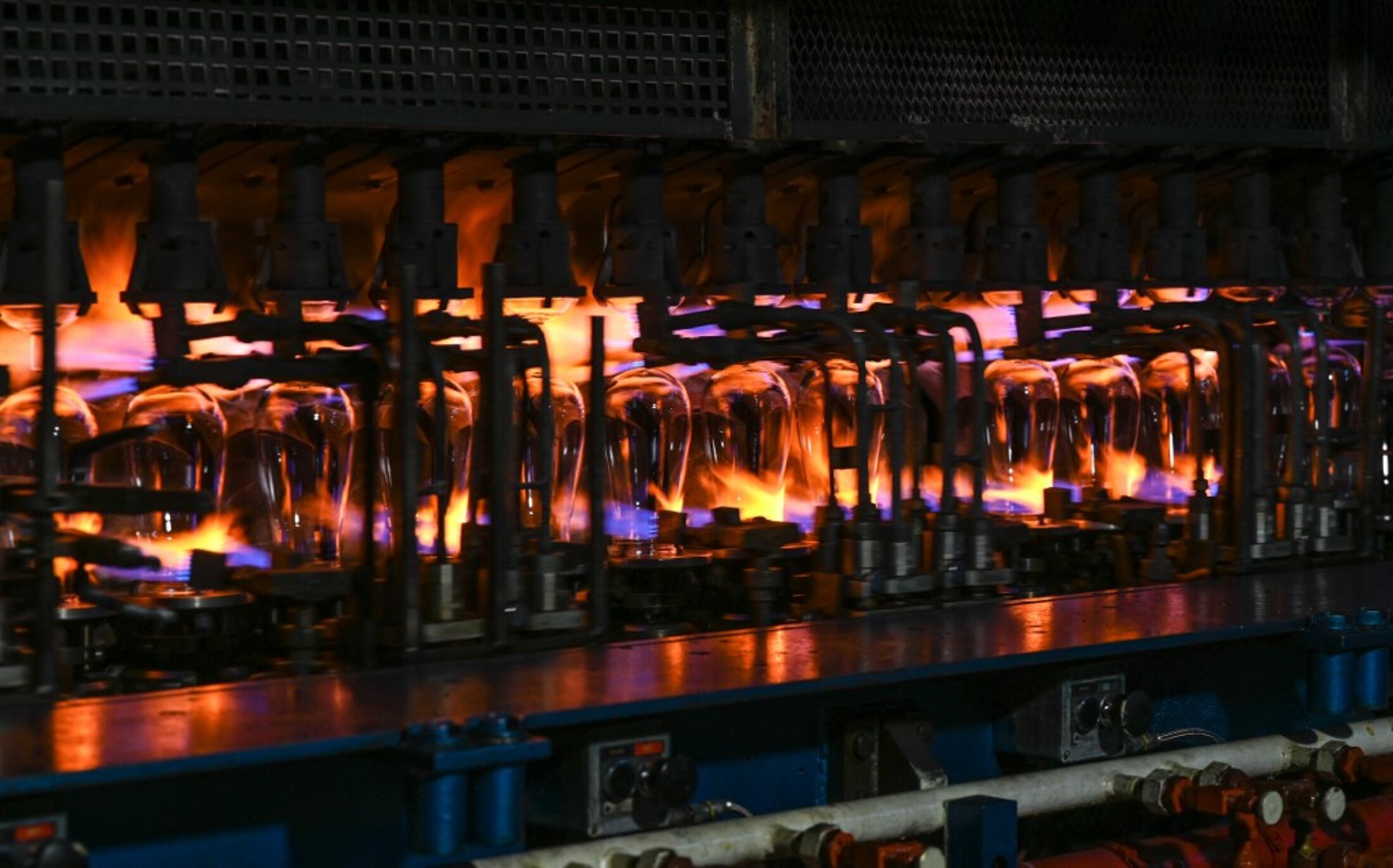

“As soon as the oven passes below 900 degrees, the glass becomes ‘cold’, dilates, and the oven cracks,” explained Serge Lechaczynski who, with his sister Anne, runs a small glass-making business in Biot, south-east France, with a payroll of 21. “So it’s impossible to switch off at night and back on again in the morning. A glass-maker’s oven has to work 24 hours out of 24, [and] 365 days per year.”

For those companies which had to renegotiate their contracts with gas or electricity suppliers in recent months, and who have been hit since the summer of 2021 by the surge in energy prices, the cost is enormous. That is the case of Duralex, based in La Chapelle-Saint-Mesmin, close to Orléans in north-central France, with a workforce of around 250.

Its energy costs for 2022 have more than quadrupled year-on-year. Known worldwide for its tempered (safety) glass products for kitchen and table use, and notably its almost unbreakable tumblers, it will this year pay a combined electricity and gas bill of 13 million euros, said its chairman and chief executive, José Luis Llacuna. That combined bill last year came to 3 million euros. The enormous hike is set against a forecast for turnover this year at a little more than 30 million euros.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Holophane SA, a French subsidiary of UK-based glass-maker Holophane, specialises in manufacturing glass for vehicle headlamps. The subsidiary, based near the Normandy town of Rouen, was earlier this month placed in receivership. Already struggling with falling sales, notably because carmakers are increasingly turning to plastic, the hike in energy costs has come as a hammer blow. “What hurts us is energy,” said its human resources director, Alain Lecompte, in an interview last week with regional daily Paris-Normandie. “On average, we were at 3.5 million euros per year, this year the bill will reach 11 million euros.”

Meanwhile, glass tableware manufacturer Arc International, based in north-east France where it employs a workforce of around 4,600, announced in September that its gas bill this year had multiplied by four. The consequences of that, coupled with a fall in sales, are that 1,600 staff have been placed on short-time working between September and the end of the year.

“The costs of energy are rocketing,” its human resources director, Guillaume Rabel-Suquet, told public regional TV network France 3. “The price of gas has multiplied by four over one year. In 2021, we spent 19 million euros for gas. In 2022, [it will be] 75 million euros. If the price of gas remains the same, it’ll be 260 million euros in 2023. Economically, it’s no longer viable.”

The managements of glass-making firms have had to begin learning new skills, according to Duralex CEO José Luis Llacuna. “In glass-making, we have all become experts in geopolitics in order to understand the how and the why of the rise in energy prices,” he told Mediapart.

When they renew energy supply contracts, the manufacturers must make a choice between signing a forward contract with a supplier who will guarantee a fixed price for the months or even years to come – but which are often very costly over the autumn and winter period –, or to take the risk of riding, day-to-day, the energy market’s volatile prices. “We are permanently confronted with colossal risk-taking,” said Llacuna. “If we get it wrong by buying at too high a cost, we put the company’s future in peril. It’s very stressful.”

Drastic measures

Unlike the giants of the worldwide glass-making industry, such as Saint-Gobain in France, which can use their position of strength to pass on the jump in energy costs to their clients, the smaller companies have found themselves powerless to deal with the crisis. They have been forced into taking drastic decisions, despite recent state aid measures announced for small- and medium-sized businesses.

Duralex is one of them, and recently placed the oven at its plant in La Chapelle-Saint-Mesmin on standby for five months, while also placing most of its employees on short-time working weeks. By doing so, it hopes to reduce its energy costs by 50% this autumn and winter. But even then, explained Llacuna, it was fortunate that his company’s sales were doing well this year and that stocks were sufficient to supply the market over the coming months, “because otherwise we would be in a far worse situation”.

In a statement released in September, Arc International announced that “the expected level of gas prices for 2023 do not allow for maintaining the level of production across all the lines”. It said it had decided “the shutting down over winter of certain ovens (between four and six ovens out of nine will be maintained in activity during this period), and the occasional use of domestic fuel as a substitute for gas”. The temporary closure of the ovens was cited as the reason for placing more than third of its employees on short-time working. However, given the size of the company and the diversification of its activities, it is expected to survive.

For the time being, Serge Lechaczynski’s small family-owned glass-making business in Biot has escaped catastrophe, thanks to protective electricity contracts signed with state-owned utility giant EDF. Nevertheless, these are being renegotiated and Lechaczynski and his sister are crossing their fingers. “If the rise is above 20 percent, it will be difficult for us to keep going,” he said.

We are looking at hydrogen, biogas, biomethane and photovoltaics

A common fear among all such small businesses now on a knife edge is to lose employees to other firms if there is a period of inactivity. “To properly train a glass-maker, it takes 12 years,” he explained.

Fabrizio Giacalone, an economist with Syndex, a consultancy agency that advises trades unions and other employee representative bodies on economic and social issues, underlined that the glass-making sector already has difficulty in recruiting staff “because of the often tough working conditions, and salary conditions that are not always attractive”.

The economic and social stakes brought about by the energy crisis are high. “We [glass-makers] often represent important employment markets in [French] towns,” said Lechaczynski. Giacalone estimates that the glass-making sector in France employs about 22,000 people, “principally concentrated in the Hauts-de-France [northern region] for half of them, and also in the south-west”.

For Duralex CEO José Luis Llacuna, the first obvious step for the industry to take in the hope of surviving the crisis is “to produce as much while consuming less energy”, but he says it must also change energy sources and reduce the carbon footprint of its activities. “We are looking at hydrogen, biogas, biomethane and photovoltaics,” he said, although he added that currently these either cost too much or are supplied in insufficient quantities. In face of that conundrum, there is a decisive role to be played by the French state, and notably the national environment agency, ADEME, to encourage businesses to move to decarbonated energy.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse