France’s Court of Justice of the Republic (CJR) on Monday found International Monetary Fund (IMF) chief Christine Lagarde guilty of negligence when she was the country’s economy and finance minister for not challenging a special private arbitration award in 2008 of 403 million euros paid out of public funds to controversial French tycoon Bernard Tapie.

However, the court ruled against handing down any sentence for Lagarde, 60, who faced up to one year in prison and a 15,000-euro fine, which means that she will not have a criminal record. In explaining the court’s decision not to punish the IMF chief, presiding judge Martine Ract Madoux said it took into account Lagarde’s “personality” and “international reputation” and because at the time of the events she was occupied with “an international financial crisis”.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Lagarde was accused of negligence in both allowing the arbitration procedure to settle Tapie’s damages claim, and also for later failing to challenge the huge payout he was awarded from public funds. The award has since been annulled and Tapie was ordered to pay back the sum.

The verdict on Monday found her innocent of wrongdoing in allowing the arbitration procedure to run its course, but guilty of deciding not to launch a legal appeal against the massive award to Tapie.

During her five-day trial in Paris last week, Lagarde had pleaded her innocence, telling the court she was “shocked” to be made to stand trial. “Have I been negligent? No,” she said.

Lagarde was appointed managing director of the IMF in 2011, after her predecessor Dominique Strauss Kahn – also a former French economy minister – was arrested in New York on charges of sexually assaulting a hotel maid. Until then, Lagarde had served as economy minister in Nicolas Sarkozy's conservative government since 2007.

She was this summer given a second five-year mandate as head of the IMF. On Saturday, Lagarde left Paris for Washington, the site of the fund's headquarters on Saturday, 48 hours before the ruling was announced on Monday. Despite the guilty verdict, it soon appeared unlikely that she would lose her job because of the absence of any sentence handed down, when she was spared a criminal record, and when she was also was given the support of the French government for her continued role at the IMF.

Late Monday, the IMF executive board announced its “full confidence” in her, and spoke of the “wide respect and trust" of her leadership of the fund.

The CJR is a special French court dedicated to investigating and eventually trying ministers accused of wrongdoing while in office. Unlike the procedure in a regular criminal court, the verdict is decided by a panel made up of six members of the National Assembly, parliament’s lower house, six senators and three magistrates.

Their guilty verdict on Monday came as a surprise after chief prosecutor Jean-Claude Marin had called for Lagarde’s acquittal during the hearings last week.

The private arbitration process at the heart of the case was decided in 2007, days after Nicolas Sarkozy was elected as president. It came after more than years of legal action by Bernard Tapie who claimed the former state-run bank Crédit Lyonnais had defrauded him during the sale, beginning in 1992, of his assets in sportswear company Adidas, in which he was a majority shareholder. At the time, Tapie had just been appointed as urban affairs minister in the then socialist government, and he was ordered by the late François Mitterrand, then president, to sell his stake in Adidas to avoid potential conflicts of interest.

Tapie, now 72, soon after claimed that the bank had deliberately undervalued his assets, alleging they were sold behind his back to a group of investors, before declaring him bankrupt due to his huge debts. The Crédit Lyonnais collapsed in 1993, and Tapie’s legal action for compensation was against the public agency responsible for the state-run bank’s liabilities.

Beginning in 1996, the claim was fought through the courts. But after Sarkozy’s election, Tapie’s former lawyer, Jean-Louis Borloo, when he was briefly economy minister in Sarkozy’s first government, in May 2007, ordered that the case be placed before a private arbitration panel. This gave Tapie an advantage for his massive compensation claim. Furthermore, it has now been established that the arbitration panel included individuals who were close to the tycoon.

Tapie, whose controversial career in business, politics and football was halted in the 1990s with a prison sentence over a match-fixing scandal, had publicly lent his support to Sarkozy’s 2007 election campaign.

Christine Lagarde succeeded Borloo as economy minister in June 2007, and allowed the arbitration procedure to run its course, despite advice to the contrary, notably from the body that manages state holdings in firms, the Agence des Participations de l'État (APE), ending with the 2008 payout.

During Lagarde’s trial last week, witness Bruno Bézard, who in 2008 was head of the APE, told the court that she should have launched a legal challenge against what he said was “such a scandalous decision” to award Tapie more than 400 million euros “even if we had only a one-in-a-thousand chance” of succeeding.

The IMF chief, a trained lawyer who was once the head of one of the largest US legal practices, was placed in difficulty during the trial, when some of her explanations for her behaviour appeared unconvincing, and when the testimony by former APE chief Bézard and former French economy minister Thierry Breton notably contradicted her defence.

Below: the CJR ruling in full (in French)

In its ruling on Monday, the CJR said the decision to place the dispute between Tapie and the state in private arbitration process was defendable at the time, “taking into account the failure of preceding mediation attempts and the multiple litigation [procedures] which, according to her, it was advisable to put an end to because of their duration and their cost”, thus acquitting Lagarde of responsibility in the process

But it considered that she was guilty of negligence in failing to challenge the massive award that resulted from it, adding that her decision not to appeal was made “19 days before the expiry of the period [for launching an appeal] allowed for by law”. The CJR underlined that Lagarde is “a lawyer by profession”, had testified that she was “personally involved in the management of the case” and had spoken of how she was “dismayed and stupefied” by the arbitration award.

The court also noted that Lagarde had not consulted an advisory report by the APE on the cost of the arbitration decision, nor studied the detail of the arbitration decision, and had failed to consult with those opposed to the arbitration process before deciding not to appeal the award made to Tapie. “All of these elements is revelatory of a negligence concerning the search for information which Madam Lagarde should have proceeded with before taking her decision,” said the CJR.

Following Monday’s verdict, French economy minister Michel Sapin issued a statement in which he said the French government took note of the CJR’s decision which “concerns events before Christine Lagarde took up her duties as head of the International Monetary Fund”, adding that she “exercises her mandate at the IMF with success and the government maintains its full confidence in her capacity to exercise there her responsibilities”.

In parallel to Lagarde’s trial, a separate judicial investigation into the arbitration procedure, in which six people have been placed under investigation – a legal status one step short of being charged – is ongoing. The six are suspected of conspiracy in fraud over the Tapie award, and a decision whether or not to send them for trial (which is when charges are brought) is expected soon. As non-ministers, their eventual trial would be held in a regular criminal court. Among the six are Stéphane Richard, Lagarde’s former chief-of-staff at the economy ministry and now head of telecoms giant Orange, Bernard Tapie, his lawyer and one of the arbitration panel judges.

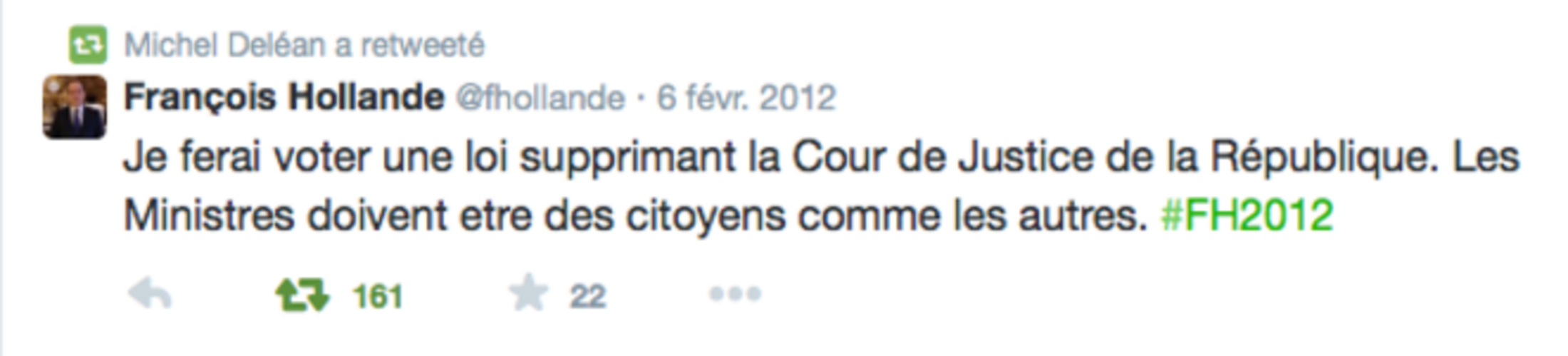

The CJR's decision not to sentence Lagarde, despite finding her guilty of negligence, will only further fuel criticism that the CJR displays a marked leniency towards the politicians whose cases come before it. It has never sent a politician behind bars. During his presidential election campaign in 2012, President François Hollande promised to disband the special court, announcing via Twitter (see below) that “politicians must be citizens like others”. However, he has since failed to honour the pledge.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

The CJR was created in 1994 following France’s tainted blood scandal, when HIV-infected blood was knowingly used to treat haemophiliacs in the early 1980s. The court, which by its nature allows politicians to escape the harsher conditions of regular criminal courts, eventually tried several former ministers on manslaughter charges in the case in 1999. Just one, ex-health minister Edmond Hervé, was found guilty – but was handed no punishment.

Until Lagarde’s trial, only two other former ministers have appeared before the CJR (junior minister Michel Gillibert, accused of fraud, in 2004, and former interior minister Charles Pasqua, also accused of fraud, in 2010). Both were handed suspended prison sentences.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse