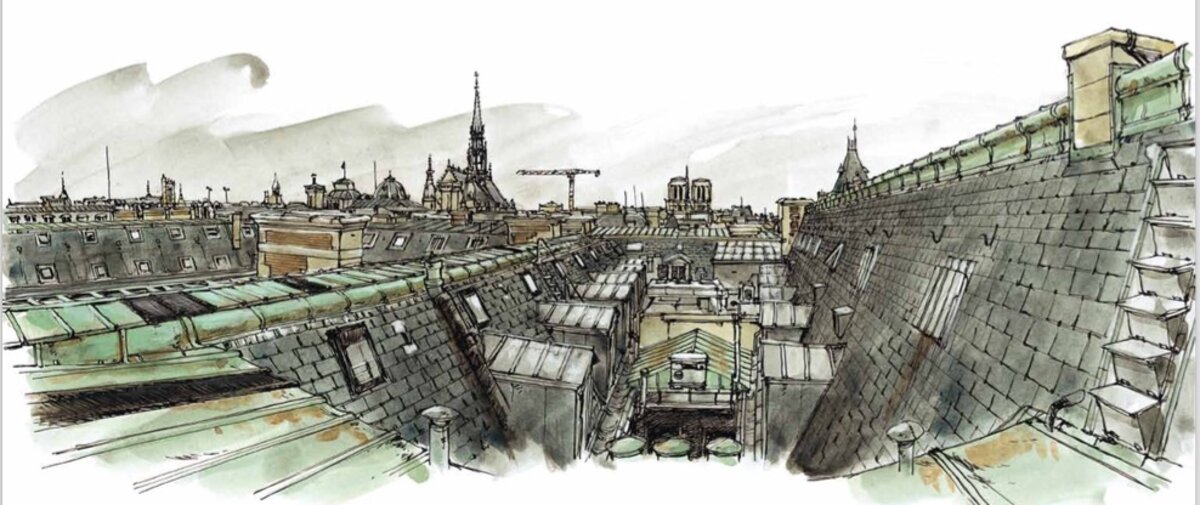

The 36 quai des Orfèvres is the address of various Paris police criminal investigation units, and in France the site is as emblematic as (New) Scotland Yard is in Britain.

Sometimes called simply “le 36”, the 19th-century building sits on a small island on the river Seine, the île de la Cité, facing south across the river towards the Latin quarter.

It reached worldwide fame as the workplace of commissaire Jules Maigret, the popular pipe-smoking police detective invented by the late Georges Simenon, has given its name to several French ‘cops and robbers’ films, is the backdrop to a number of French TV series, including Spiral, and even became the name of an annual literary prize awarded to new detective novels.

Less glamorously, it hit news headlines in 2014 when it was discovered that a stock of 52 kilos of cocaine, stored in the building after police hauls, had disappeared, in an ongoing case in which several officers are implicated. In a separate, sordid case that also emerged last year, several officers are accused of the rape of a Canadian woman tourist they are alleged to have lured into the building from a nearby bar.

Meanwhile, the head of “le 36”, Bernard Petit, was suspended from duty in February this year on suspicion of having revealed information from confidential case notes to suspects in the investigations. The catalogue of woes prompted weekly magazine L’Express to headline: “The 36, quai des Ofèvres, the end of a myth?”

While the police services are now due to move out of the building in 2017 for a new site in the north of the capital, after serving more than 100 years as Paris police HQ “le 36” is unlikely to lose its long-earned aura or its fictional appeal as the backdrop for TV series like Spiral and its grubbily-dressed hard men and women detectives who occasionally break the rules.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

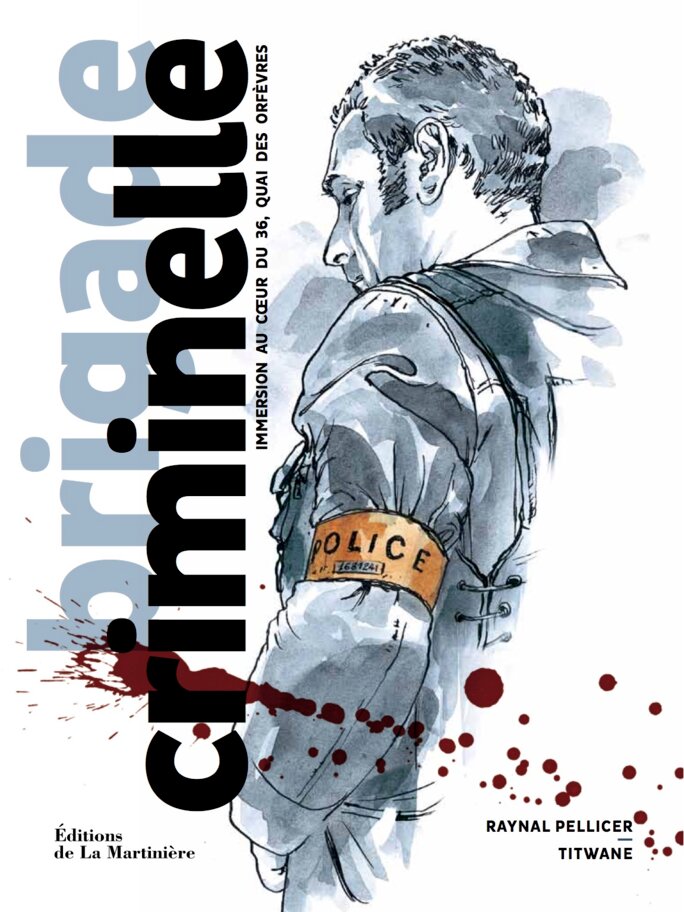

The “36” is home to the Paris police serious crime squad, la brigade criminelle, as well as a number of other police services. Its boss, Marc Thoraval, nicknamed by journalists as “Mr No”, last year exceptionally opened up the doors of his team on the fifth floor of the building to documentary filmmaker and writer Raynal Pellicer and his illustrator colleague Titwane for their second book about the workings of “le 36”.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

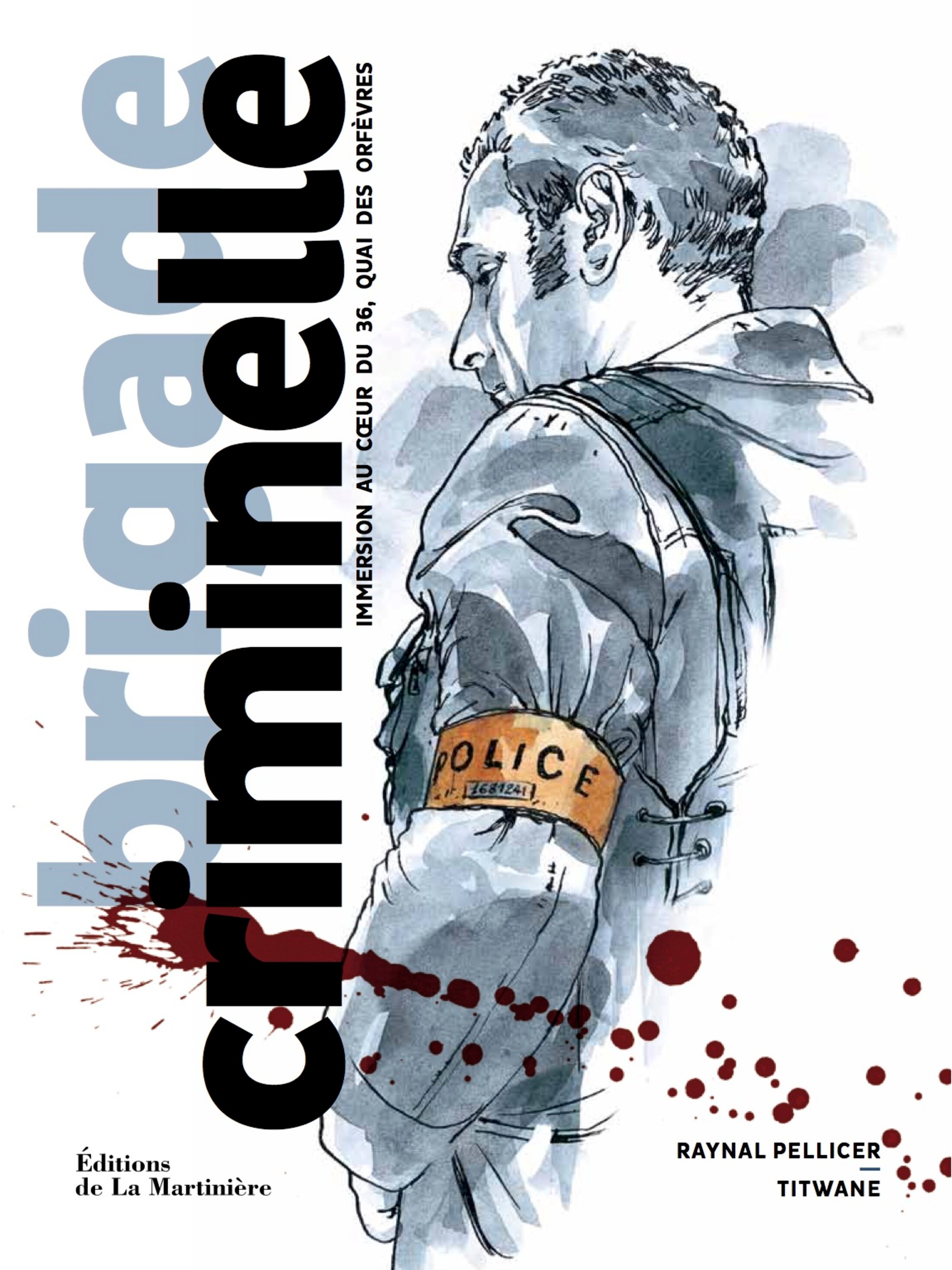

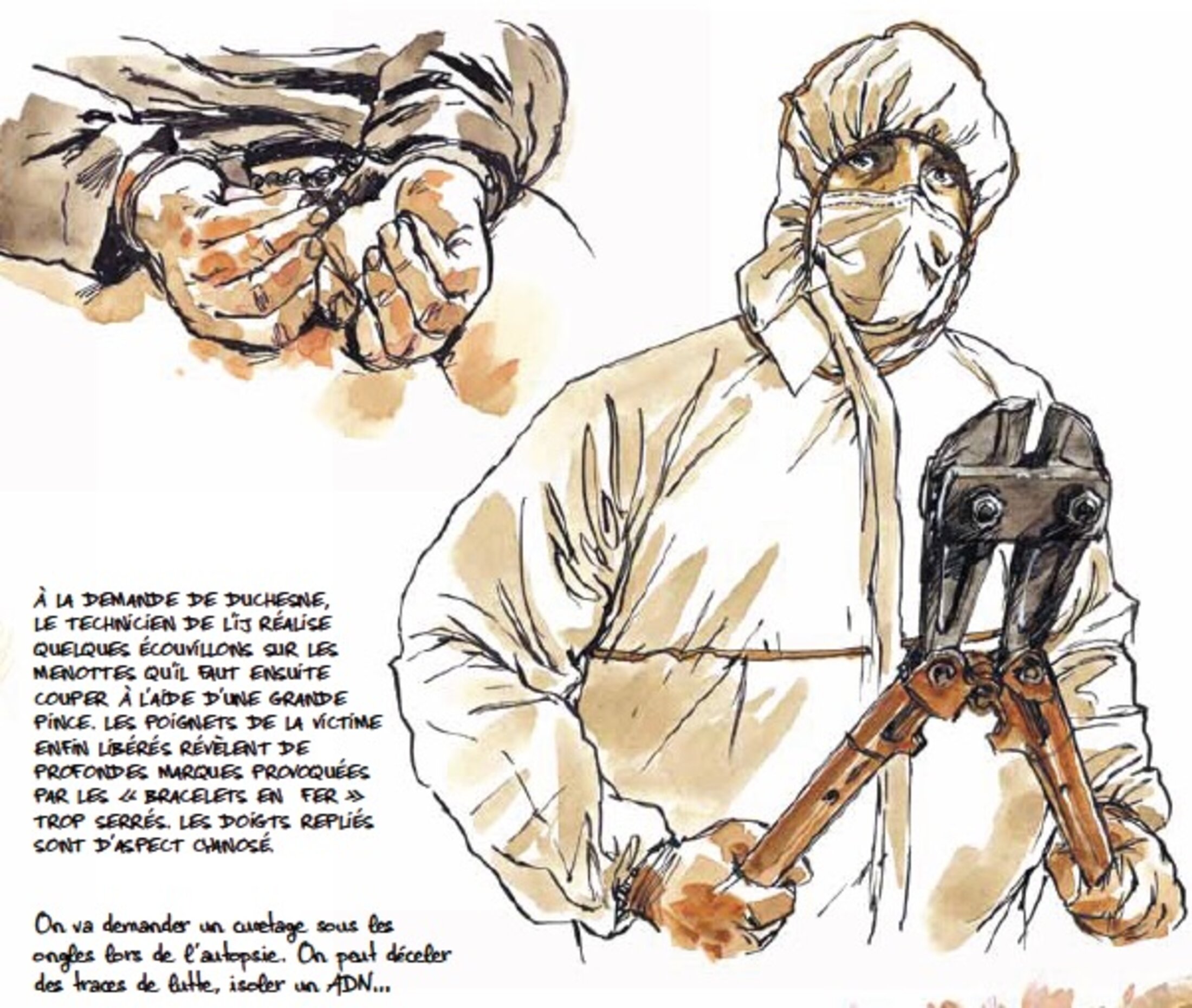

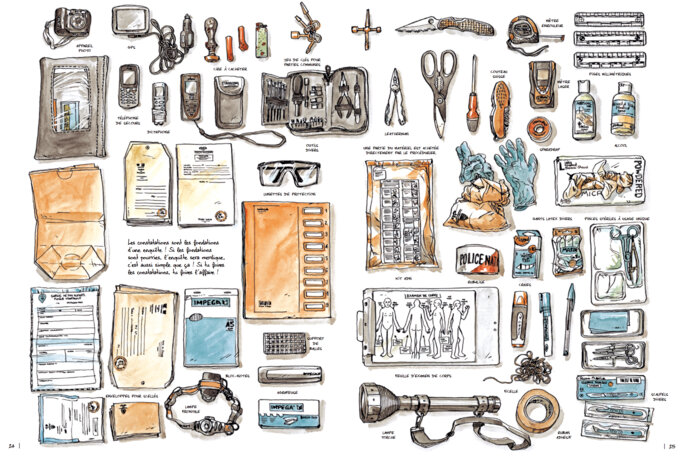

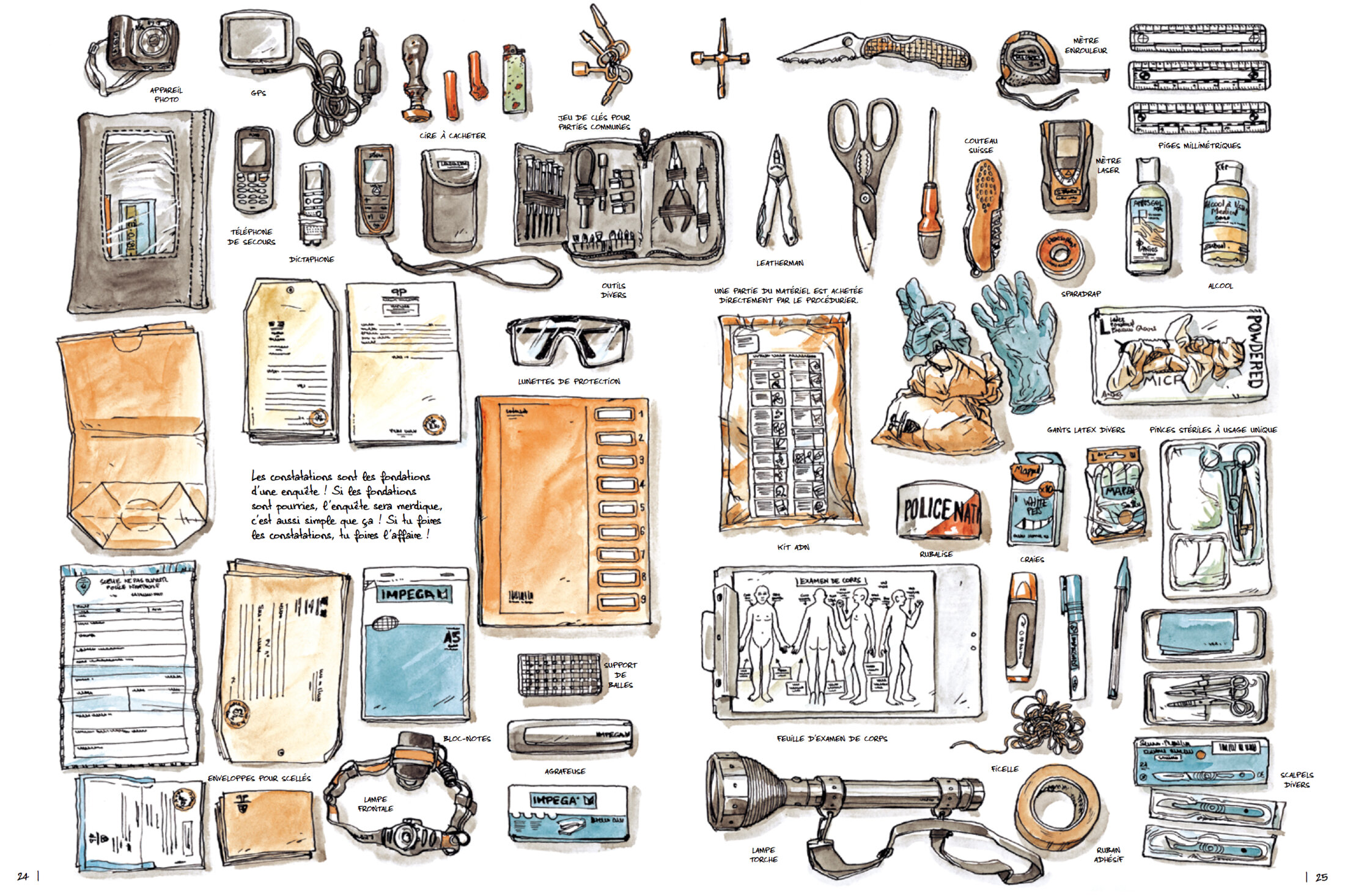

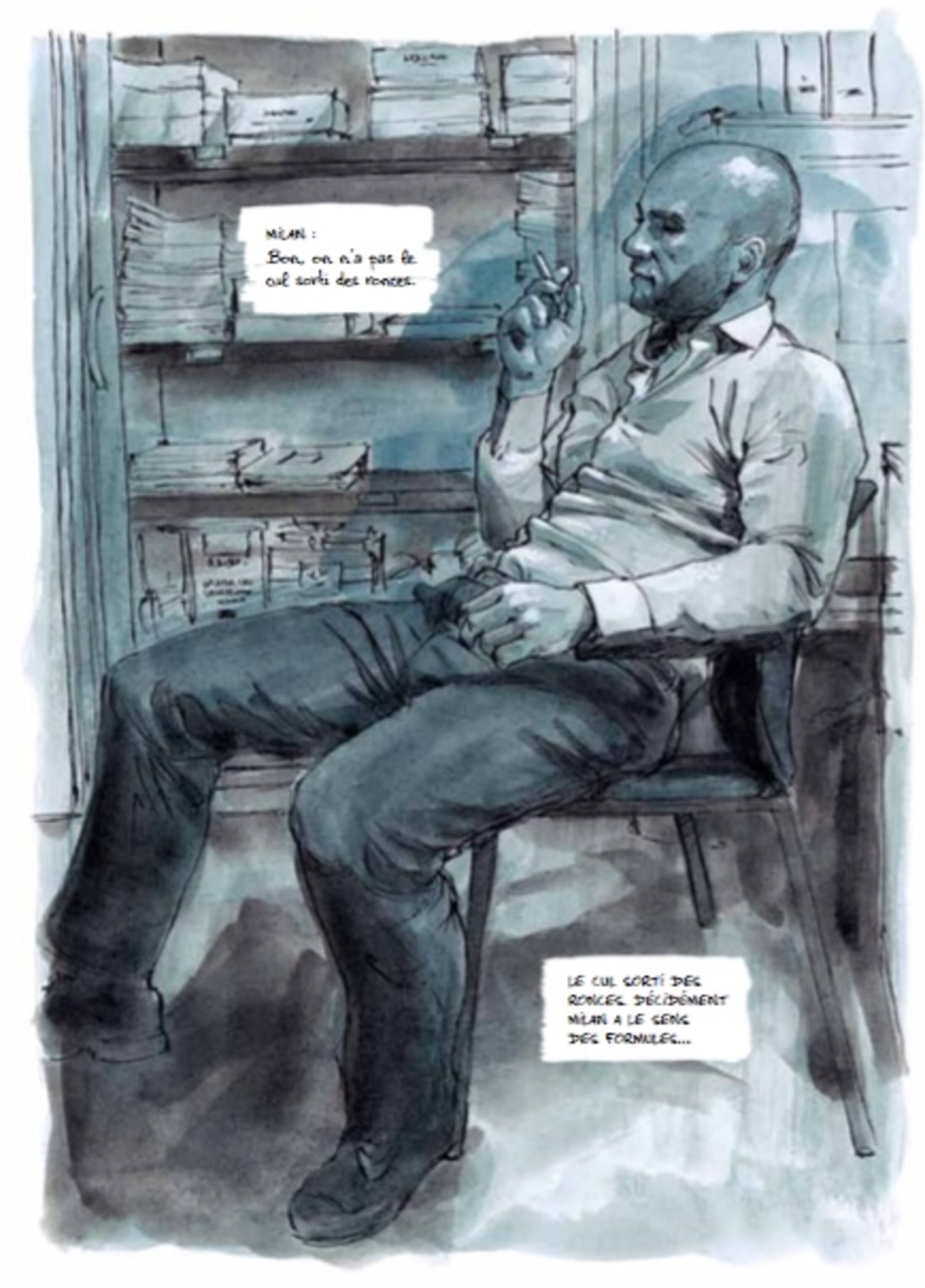

Like the first, which was published in 2013 and which centred on the organised crime squad, the Brigade de répression du banditisme, or BRB, the pair present in fine detail, in words and illustrations, the daily reality of the police operations. For this second work, Brigade criminelle, immersion au cœur du 36, quai des Orfèvres, which was published in France on September 17th, Pellicer followed the serious crime squad over a period of 15 weeks, between March and July 2014, taking notes and photographs, building up his texts and providing Titwane with pictures for his illustrations.

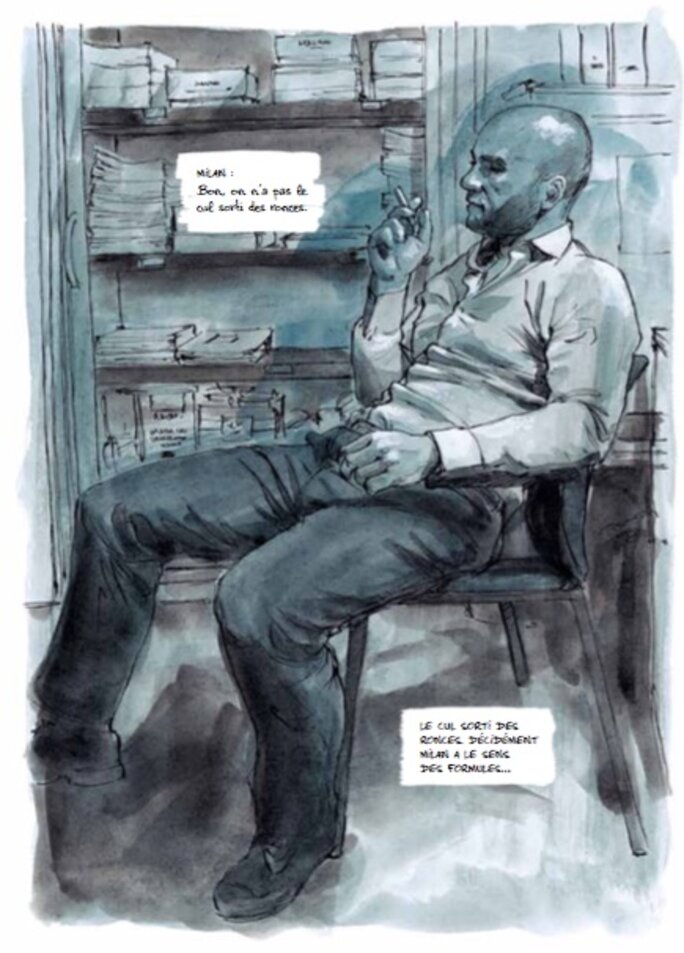

The book is far from the image of “le 36” as portrayed in TV series. It shows the day-to-day reality of the squad, the fastidious paperwork the officers are regularly involved in and the slowdown time between two criminal investigations which the officers call “the false rhythm”.

Pellicer cites one of the serious crime squad officers who warned him early on that: “At the BRB, you’re up against apple thieves. But here, every case is a drama. You’re going to meet evil.”

Pellicer underlines the difference between the two squads that he has followed. “There could be time off at the BRB after a questioning session, when the police officers and the suspects relax a little, share a cigarette, talk about a third party. At the serious crime squad, there is a wall between the police and the suspect.”

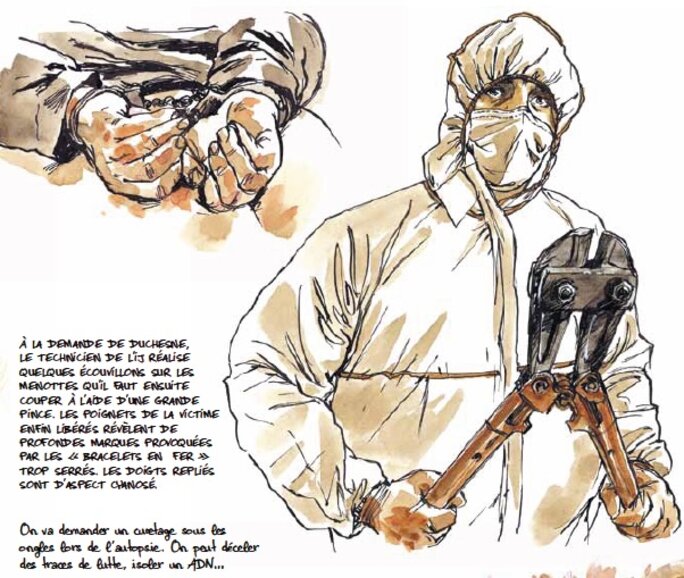

He said he took a huge number of photos not only to guide Titwane in his illustrations, but also sometimes to “place a filter” between himself and what was in front of him. “Before entering my first crime scene, a woman officer told me ‘I’ll give you a piece of advice. Work, don’t put yourself in the position of being a passive observer’.”

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Whereas the BRB investigates cases of holdups where the value of what is stolen is superior to a certain sum, the serious crime squad is involved in all kinds of cases regardless of their social or financial distinction, from murders of homeless people to the death of Princess Diana. It handles about 30 cases per year, and holds on to them until they are concluded. The oldest case is that of the 1980 bombing of the Paris rue Copernic synagogue.

We learn from the book how the teams are split into a hierarchy of nine units, all of which have a very precise task. These include the group leader, who is the first to enter a crime scene, and what are called the “rippeurs”, who carry out the door-to-door enquiries, and also the person who looks after making sure that the handling of the investigation sticks to the strict letter of the law, called the procédurier.

Titwane worked with Chinese ink and water colours using the photos taken by Pellicer (who has written several books on photography). Titwane said he tried to keep “a spontaneity in the stroke” of the pen and brush. Between the accounts of two crime scenes, there magnificent double-page spreads of illustrations which bring some much needed relief to this otherwise dark universe. “Raynal gave me his text, I set out the way it was cut up, then we did lots of coming and going to ensure the text and images were one.”

Enlargement : Illustration 4

In many of the investigations mentioned, far from the world of Maigret, technical methods are omnipresent, such as DNA testing, CCTV video, and geo-localisation. Despite this, however, the book’s best pages concern a recent case with what could hardly be a more classic, if sordid, plot. A couple of lovers are suspected of murdering the woman’s husband in order to get their hands on a small inheritance. But despite their incoherent statements, and lies, there is no solid evidence in the form of fingerprints or DNA samples to prove the case against them.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

The book takes us through the long hours during which the couple are questioned by the officers of la crim’, as the serious crime squad is also known, but without appearing like a voyeuristic exercise. “The presence of an outside observer during the questioning, on top of a lawyer and sometimes an interpreter, was not an easily acceptable situation for the officers, but it’s fascinating, because it is nothing other than verbal jousting,” Pellicer recalls, adding that the exchanges see the different parties swapping in and out of the use of the ‘tutoiement’, the more intimate form of “you”.

While the authors managed to reach agreement with the police heirarchy for their project, the process was more complicated when it came to the magistrates who, under French law, are at the head of an investigation into a serious crime. In France, ‘examining magistrates’, who have the rank of judge, assign an investigation to a police or gendarmerie team, who carry out the work in the field and who report back. The magistrates may also themselves order particular lines of investigation or forensic tests, and will decide if, at the end of the investigation, there are grounds for charges to be brought and defendants sent to trial.

By law, those implicated in a case will remain innocent until proven guilty, and most of the cases that Pellicer and Titwane had access to are still under investigation. “It is the difficulty with this type of fly-on-the-wall reporting, where there are necessarily violations of the secrecy of the investigation,” says Pellicer. “A police officer in fact offered a good verbal formula on the subject: Do you know what the difference is between ‘implicated’ and ‘involved’? In a dish of bacon and eggs, the chicken is involved, but the pig is the only one implicated.”

The authors are now working on ideas for a third book about “le 36”, perhaps including the day-to-day actions of the magistrates, what the police call the “after-sales service”.

-------------------------

Brigade criminelle, immersion au cœur du 36, quai des Orfèvres is published in France by éditions La Martinière, priced 29.90 euros.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article is available here.

English version by Graham Tearse