The claims that the anti-malaria drug chloroquine, which is also used for treating auto-immune illnesses such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, could prove to be successful in treating Covid-19 virus infection have excited interest worldwide, especially in the absence of a vaccine which is forecast as unlikely to appear before 2021.

Chloroquine is what is known as a broad-spectrum antiviral compound that can increase a cell's pH values – making it more alkaline – and thus help to block infection from the pH-dependent virus. It has already been tested in a laboratory where it has shown itself to be effective in blocking infection from different viruses, such as the flu, dengue and that of chikungunya. But trials into its effectiveness in treating the Covid-19 virus continue and, at least for the moment, the scientific jury is still out.

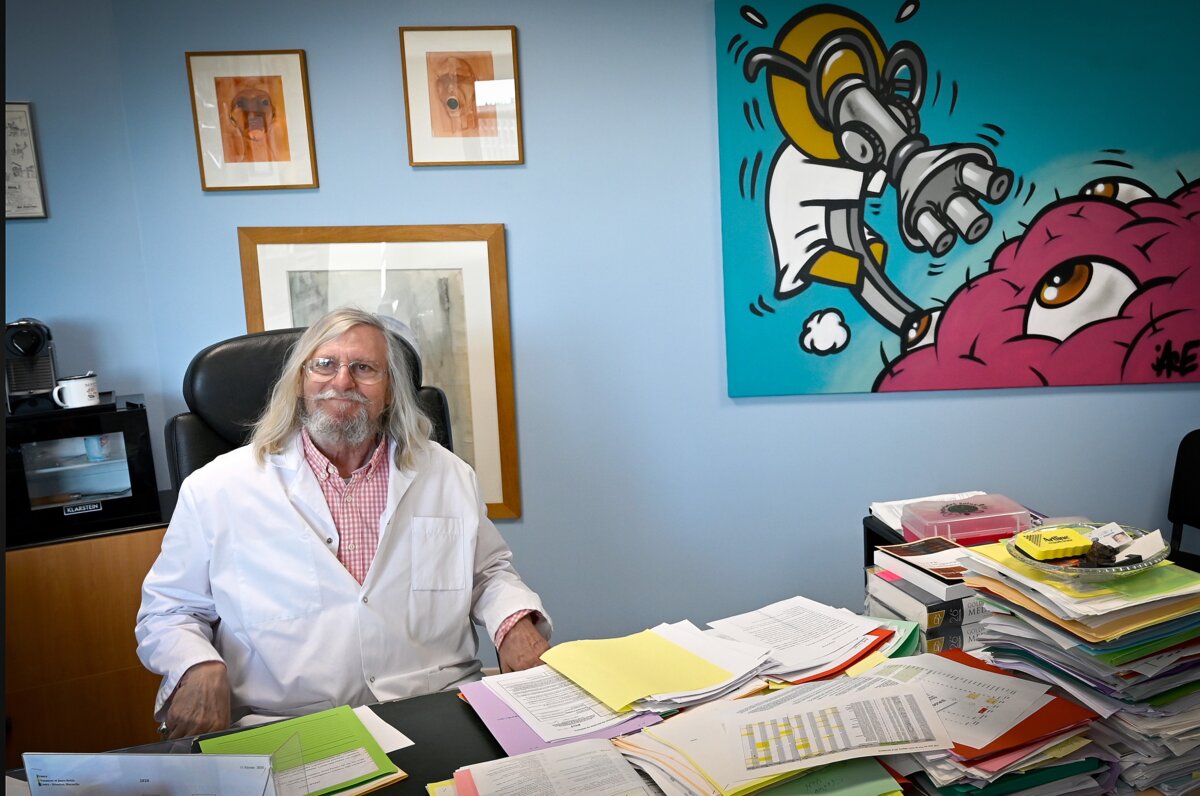

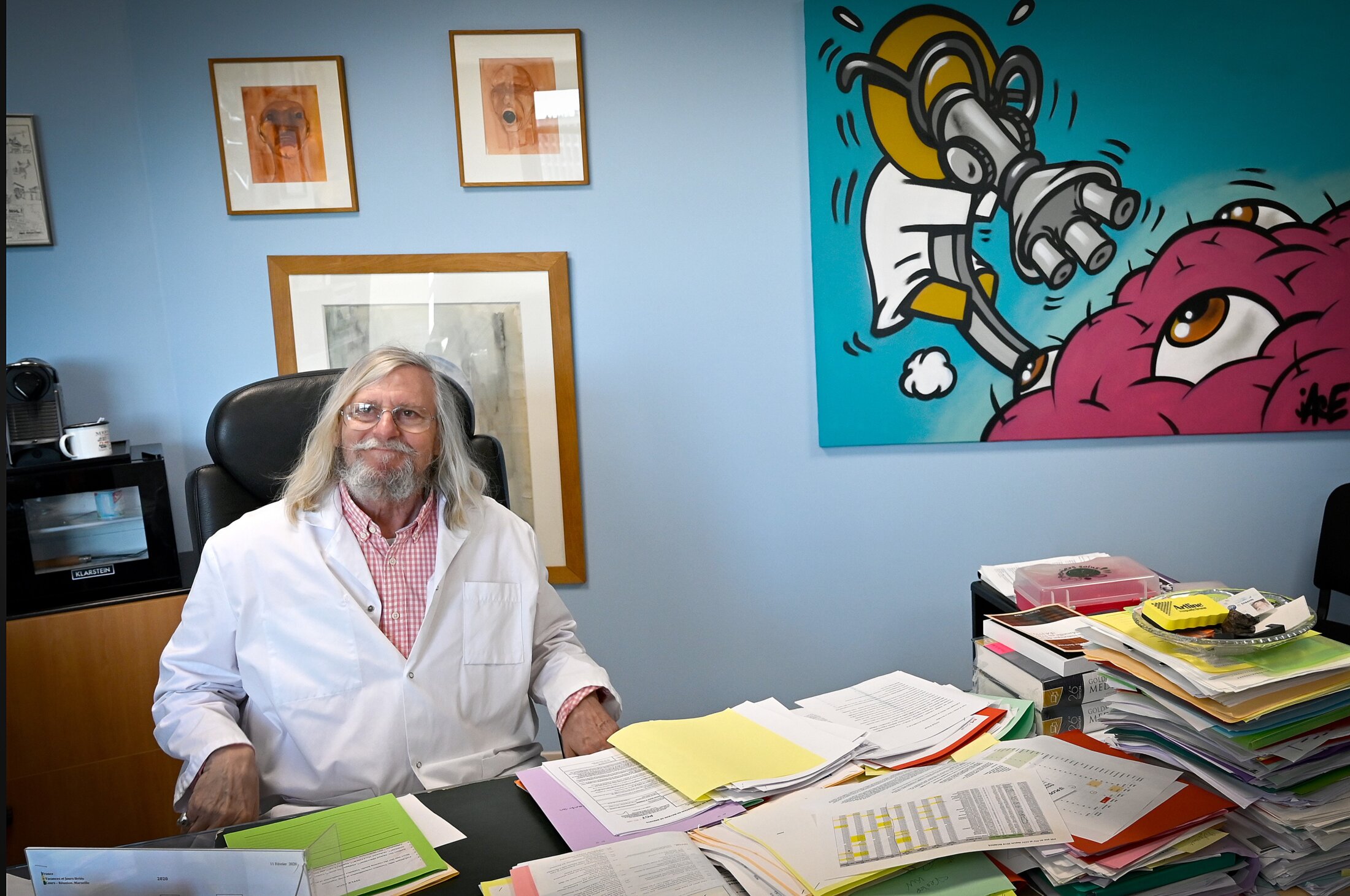

What is certain however is that the heated debate among the global scientific community over its effectiveness in treating the infection centres upon the figure of its champion, Professor Didier Raoult, a microbiologist and director of the IHU Méditerranée Infection foundation in the southern French city of Marseille, where he is the very active head of its infectious disease laboratory.

The IHU is a public body, created in a partnership essentially between Aix-Marseille University, France's insititute of research for development (IRD) and the Marseille teaching hospital administration. As a foundation, it also receives private funding, notably from biotech multinational bioMérieux.

In a high-profile visit las week, French President Emmanuel Macron travelled to Marseille for discussions with Raoult about the possible use of the drug, as France prepares to progessively scale down its lockdown on public movement as of May 11th. Raoult has since early this year championed chloroquine’s virtues in combatting Covid-19, and amid doubts in some quarters over his claims he presents himself as a victim of attacks by Parisian scientific circles with links to the pharmaceuticals industry.

While rarely has a medical expert such as Raoult – a left-field maverick for some, a maligned hero for others – been the target of so much criticism, this investigation by Mediapart shows that the doubters cannot be easily dismissed as a gang of ball wreckers; they level serious accusations of biased research results, methods that lack scrupulous methodology, and a secrecy surrounding the funding of his work.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

In January 2018, and despite an undoubtedly brilliant career, Didier Raoult lost his affiliation to France’s prestigious interdisciplinary scientific research network, the CNRS , and also with the no-less prestigious French national institute of health and medical research, INSERM.

Mediapart has obtained access to the findings which led to the move. These were the conclusions of a report commissioned in January 2017 by France’s high council for the evaluation of research and higher-education teaching, the HCERES, an independent administrative body. The evaluation report was compiled by a panel of European researchers, notably including scientists from the British public research university, University College London (UCL), the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine, Germany’s leading tropical medicine institute based in Hamburg, and the Paris-based foundation for research into infectious diseases, the Institut Pasteur.

Their conclusions gave a scathing appreciation of studies conducted by Didier Raoult’s laboratory unit of research into infectious and tropical diseases, part of the IHU Méditerranée Infection foundation, called URMITE. When their report was prepared in 2017, the URMITE laboratory was already separated into two entities that were to be officially established in 2018, called MEPHI and VITROME.

According to the evaluation panel, “the bulk of research” of one team was “exploratory-orientated, focussing on the discovery of new microbial forms, and it was difficult for the panel to see the scientific/epistemological benefits, in the absence of further characterisation that, for example, demonstrates pathogenicity”.

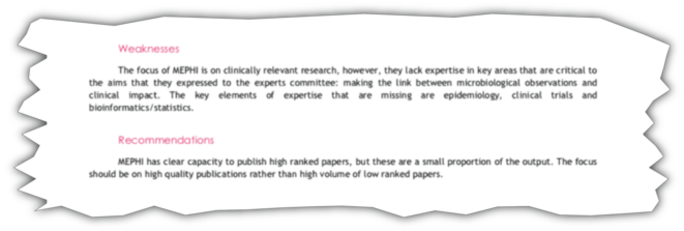

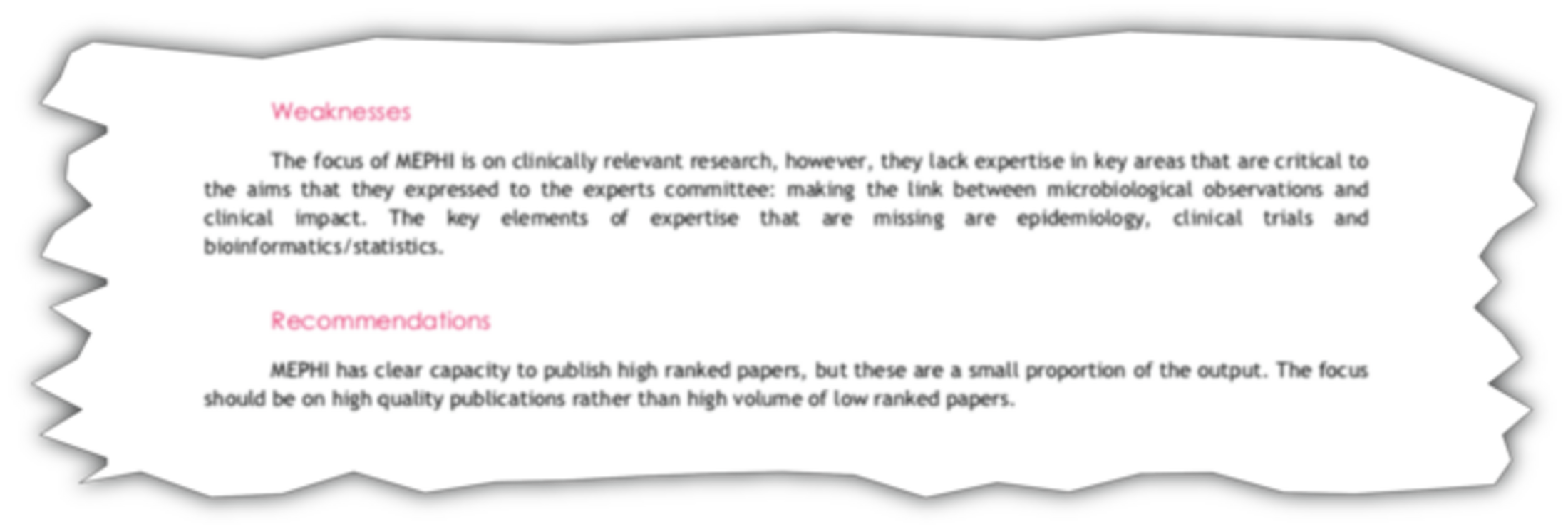

Concerning MEPHI (an acronym for “microbes, evolution, phylogenesis, infection”), dedicated notably to identifying new bacteria and viruses, the evaluating panel found that it showed a “lack of expertise in key areas that are critical to the aims that they expressed to the experts committee: making the link between microbiological observations and clinical impact”, adding that, “The key elements of expertise that are missing are epidemiology, clinical trials and bioinformatics/statistics”.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

While it had “a clear capacity” to publish highly ranked scientific papers, these represented “a small proportion” of its output, and the evaluation panel advised that “the focus should be on high quality publications rather than high volume of low ranked papers [sic]”.

The panel said that a search of URMITE-related papers published between 2011-2016 available on the Web of Science – a website of citation data produced by the then Institute for Scientific Information – found “1,153 papers of which only four are defined as ‘highly cited’”.

“The search for new pathogens, or evidence of a known pathogen in a new host, means the unit can be described as ‘stamp collecting’ or ‘fishing’, without significant characterisation of what has been newly discovered,” the panel said.

The panel also noted that there appeared to be “an excessive emphasis on publication volume”, and that while that was partly understandable because of the nature of the unit’s activity and the need for PhD students to publish, “creating a new journal ‘New Microbes and New Infections’, allegedly to publish papers that cannot be published in existing journals feels a bit desperate”. Several researchers from URMITE sat on the journal’s editorial committee, led by Professor Michel Drancourt, head of MEPHI and something of a right-hand man to Didier Raoult.

They also noted that the “cohesion” of the team appeared to be “largely built on the energy and personality” of Raoult, developing “what could be deemed a siege mentality”, adding that, “A less adversarial approach to the rest of the scientific community would be useful”.

Former INSERM director says the facts were 'buried'

Paul (not his real name, which is withheld on his request) worked with Didier Raoult as an engineer, leaving the foundation's URMITE unit in 2016. “I was on the identification of new bacteria,” he told Mediapart. “And to find new bacteria in that way is about numbers, because a new bacterium leads to a new publication, which both guarantees the reputation of the laboratory and money.”

In France, a software system called SIGAPS (for “Système d’interrogation, de gestion et d’analyse des publications scientifiques”) is used to record and evaluate scientific publications by research teams, allocating a score of points for their studies and which in turn determines a remuneration.

To this backdrop, Paul said he found no “scientific interest in this work”, which he described as “quantitative, for show, and lucrative”.

Another report into the activities of Professor Raoult’s URMITE laboratory, also dating from 2017, was drawn up by members of the hygiene, safety and working conditions committees – these structures, known as CHSCTs, are common across France – from the four public bodies directly involved with the unit’s work – the CNRS, INSERM, the University of Aix-Marseille and the Institut de Recherche pour le Développement. The latter is a government-affiliated establishment, based in Marseille, whose activity centres on scientific and technological cooperation with developing countries.

The report by the CHSCTs – composed of representatives of personnel and the administration – was prompted by a letter of complaint from 12 staff at Raoult’s IHU foundation laboratory. Obtained by Mediapart, the report highlighted cases of harassment (as previously reported by Marsactu, an online investigative news site for the Marseille region and editorial partner of Mediapart), and also serious breaches of safety rules.

The CHSCT delegation’s report noted that the laboratory’s staff “manipulate pathogenic biological agents in non-reglementary premises”. Some technicians and students were found to be working with chemical, carcinogenic, mutagenic and toxic products for reproduction under defective air extractors. “The culture of human cells as well as the manipulation of blood products of unknown sanitary status are carried out in ordinary laboratories,” it added.

After several engineers at the site had made known their fears of reprisals if they were to speak out openly, the CHSCT delegation authorised written testimony on condition that the statements were authenticated. Out of seven of these statements, two claimed to have been involved in the misreporting of the conclusions of their work. One was an engineer who described the “falsification of the results of an experiment at the request of a researcher”, while another who “questioned the scientific rigour in obtaining certain results”.

Several engineers and researchers gave similar accounts to Mediapart. One of them was Mathieu (not his real name) who prepared his doctoral thesis working at the lab under Raoult, who he said “doesn’t permit discussion”. He spent four years at URMITE. “We go about things the opposite way around, he has an idea and we carry out tasks to prove that he’s right,” he said. “With the fear of contradicting him, that can lead to biasing results. Whereas, it’s doubt and discussion that allows science to progress.”

Mathieu recounted what he said was his first meeting in the presence of Raoult: “It was a Wednesday afternoon, during a work-in-progress. That’s the moment when those preparing a thesis present the state of their research. We had five minutes to present what is sometimes three to four months of work. That’s very short. When there was the least disagreement, Didier Raoult would say, ‘You’re not here to think, it’s me who does the thinking’.”

In 2015, Mathieu decided to leave the lab, although he had been invited to stay on. “I was working on a subject on which Didier Raoult had given me an angle of research and, with the passing of the tests I saw that he was wrong because on every occasion my tests proved negative. I was asked to persevere and I spent almost a year doing them to prove he was right. Following dozens of repetitions, without anything completely positive, there was a signal in the sense of [what] Raoult [argued]. It was approximate, even biased in the approach, and so also in the results.” Despite that, he said, his doctoral advisor, a close colleague of Raoult’s, told him his study was to be published.

“Given the poor level of this study, and the problems it posed in its scientific approach, at the very least questionable, we spent one year presenting it before journals which refused [to publish] it, pointing to the lack of scientific rigour and, in particular, the missing experiments and checks,” Mathieu said.

The publishers’ written rejections, which Mediapart has seen, and which were addressed to Raoult, included the comments “The results are not sufficiently solid”, “lack of knowledge”, “the data is for the most part descriptive”. The paper therefore did not convincingly demonstrate the initial hypothesis behind the study. It would later be published, signed off by Raoult, in the journal Microbial Pathogenesis, on whose editorial board sat Didier Raoult.

Mathieu alleged that Raoult “shatters any person who is not going in his direction and, like this, holds everyone in fear”, adding that since leaving the lab “I don’t feel animosity, but rather concern and wariness”. He says he regrets putting his name to a paper which presented biased results and, because his research grant depended upon the unit, failing to protest. “Not only did I depend upon Raoult for my studies but I had also observed how his reputation allowed him and others close to him to smash the career of those who contested him,” said Mathieu.

In 2006, Didier Raoult and several colleagues were handed a one-year ban by the American Society for Microbiology (ASM) from publishing in any of its journals. That move followed the discovery by a reviewer for the ASM publication Infection and Immunity that a paper submitted to it by Raoult and his co-authors about a mouse model for typhus had misrepresented figures it contained. Raoult protested his innocence in the affair, which was explained by his co-authors as an innocent mix-up by them, but he lost his appeal before the ASM. In anger, he in turn banned his lab from further collaboration with ASM journals.

Antoine (not his real name which, like in the cases of Paul and Mathieu, he asked to be withheld) is a researcher with the health and medical research institute INSERM, who once worked at the lab. Before detailing a confrontation with Didier Raoult, he insisted on making clear that he did not want to become involved in what he called the “regrettable” controversy surrounding the professor’s championing of the use of chloroquine in treating Covid-19 infection. “Whether this treatment be good or not, more precautions should have been taken before announcing it, there being no clinical trial that, until now, allows to pronounce upon its effectiveness,” he said.

But for Antoine, the early claims about chloroquine by Raoult came as no surprise. “He always wants to be the first, and that he’s talked about,” said Antoine. “Which leads him to move fast but the rigour of the scientific method is sometimes open to criticism.”

He recounted how he came into confrontation with the professor over the discovery of a new strain of virus. Antoine refused to put his name to a paper intended for publication in which, he said, Raoult wanted to present his interpretation of the manner in which the virus functioned. “But we did not have sufficient elements of proof to go so far in the interpretations,” he said. “To do so could lead to making assertions that were not scientifically demonstrated.”

He said he left the lab because he felt the work there was too descriptive through a lack of thorough reflection, and was also little satisfying from a scientific point of view, but above all that “the methods are questionable in terms of rigour”. He added: “Raoult often said, ‘when I say something, it’s that it’s right.”

“This question of biased results is not unique to Didier Raoult’s laboratories, but it is inadmissible that it be not spoken about,” said Dominique (not her real name), a professor and former head of a unit at INSERM. “It is that which is the problem, that bodies like the CNRS or INSERM don’t react quickly.” She said she had alerted both to the issue in 2006 and 2009. “I alas noticed this lack of deontology.” She recounted how, a little more than ten years ago and at the request of the CNRS, she led a visit to the URMITE unit by a commission of evaluation, one of what are regular assessments of research laboratories. “What struck me was the obsession of Didier Raoult with his publications. A few minutes before the evaluation of his unit was to begin, it was in fact the first thing that he showed me on his computer – his h-index.” The “h-index” is a measure of the productivity of a scientist in publishing papaer, and their the level of subsequent citations. “I didn’t let myself be impressed by this kind of reference, which matters little to me,” she said.

“We always take a moment to meet the teams without their director,” Dominique continued. “His laboratory welcomes numerous foreign students […] we were able to notice pressure exerted upon them, being in a more precarious position than the other researchers. Some also alerted us about studies whose results were arranged.”

She said that her committee’s report subsequently submitted to the CNRS and INSERM went unheeded. “I think that at that time, the acclaim for Didier Raoult convinced them to bury these facts, having themselves an interest in supporting a director with such an h-index.”

In 2010, Raoult was awarded the Grand Prix Inserm award in honour of his entire career. It was not until 2018 that both the CNRS and INSERM would take disciplinary measures over the practices of the professor’s laboratory.

Mediapart submitted a series of questions to Didier Raoult concerning the 2017 scientific evaluation report commissioned by the French high council for the evaluation of research and higher-education teaching, the HCERES. A response was received from the Yanis Roussel, a doctoral student who is the head of PR for the professor. “Concerning the scientific part, our work is evaluated by a scientific council,” he replied, referring to the IHUs own council of independent scientists. “We believe that as outside experts, they are best placed to comment on the pertinence of the work carried out at the IHU.”

The president of the council in question, oncology professor Laurence Zitvogel, held until September 2019 a 39% stake in a company called Everimmune, a start-up which works with Raoult’s foundation and which is run by Zitvogel’s sister, Valérie Zitvogel-Perez.

The unanswered details on funding by pharma firms

There was one issue which the 2017 HCERES evaluation committee of European scientists was unable to verify for lack of information, and this was the funding of Raoult’s laboratory and its projects.

While Professor Raoult insists he is independent, his foundation has received a total of 909,077 euros since 2012 from pharmaceutical firms, according to figures released by the French health ministry. The Institut Mérieux, the Mérieux family holding company which notably controls biotechnology multinational bioMérieux, is a founding member of the foundation and sits on its board, and has provided the laboratory with a total of more than 700,000 euros. French pharma giant Sanofi has handed it 50,000 euros.

On the website of the information transparency collective Euros For Docs, which provides simplified access to the French health ministry’s data on legally required declarations of interests between health sector professionals and drugs firms, the name of Didier Raoult does not appear – only the name of his foundation figures in the data.

Similarly, there is only mention of “donations” for operational activities, and occasionally “remuneration”, but without any further detail. The opacity stems from the legal status of “foundation” which was chosen for the creation in France, in 2010-2011, of six public hospital-university establishments, called “instituts hospitaliers universitaires”, or IHUs, including that of Didier Raoult. One of the notable reasons these were established as foundations was to facilitate private funding.

Amid the concerns about the transparency and governance of such entities, and following a report by France’s social affairs inspectorate, the IGAS, the health ministry and that of research and higher education announced in 2016 that future IHUs would not operate as foundations.

Raoult’s IHU remains a foundation. Mediapart attempted to clarify the amounts and purposes of the funds given to the professor’s foundation by pharma firms. This involved a consultation of information provided the foundation itself and the French health ministry’s data on declarations of interest published on its dedicated website transparence.gouv.

According to the declarations, Mérieux has paid the foundation a total of 715,077 euros, including for “operational” funding and “partnership” deals, and also including a “remuneration” of 165,000 euros.

The Institut Mérieux subsidiary bioMérieux is active in manufacturing tests for Covid-19 virus infection. Questioned by Mediapart, the Institut Mérieux said that there had been “no collaboration whatever” with Raoult’s IHU concerning the production of the tests. It added that “as a cofounder [of the foundation] and in the framework of a partnership agreement”, the Insitut Mérieux “pledged funds of 125,000 euros per year for the period between 2012 and 2015, and of 25,000 euros per year for that between 2016 and 2021.” It insisted that, “This concerns donations and in no case remunerations”.

It said funding from its biotech subsidiary, which had handed the foundation 165,000 euros between 2012 and 2014, was “to carry out, some years ago, collaboration with the IHU in the field of tuberculosis”. According to Mérieux, the funding was for “the expenses of a doctoral student at the foundation [who was] principally posted to research activities on a programme led by Professor Raoult into tuberculosis”. Mediapart was not given neither the name of the student nor the title of the doctoral thesis.

According to several doctoral students questioned by Mediapart, the grant given to them by the IHU varies between 1,000-1,400 euros per month. On that basis, the student involved in the research into tuberculosis would have received a sum of between 36,000-50,400 euros. That would leave a minimum 114,600 euros from the total 165,000-euro funding by bioMérieux, which was on top of the Institut Mérieux yearly donation of 125,000 euros for the operational costs of the foundation’s laboratory.

Contacted over what the remaining sum was used for, the Institut Mérieux invited Mediapart to question Didier Raoult.

In place of Professor Raoult, it was the president of the foundation, Dr Yolande Obadia, who fielded Mediapart’s questions. She declined to provide the details of the doctoral thesis concerning the research programme on tuberculosis, nor the beneficiaries of the 165,000 euros provided by bioMérieux, which she said was because of “a strict clause of confidentiality for all the contracts we sign with industrialists”.

Obadia did however reveal that bioMérieux provides an annual 1.2 million euros to the foundation’s yearly operating budget, which currently totals 120 million euros – of which 60% is financed by the French state-run research agency, the “Agence nationale pour la recherche” (ANR).

She said that it was quite proper that the Mérieux group, via the Institut Mérieux, should sit on the foundation’s board, as provided for under its articles, in the same manner as do public bodies, adding that the presence of Mérieux “as a founder and in the governance of the foundation is a necessity for the IHU, whose objective is to have a global strategic vision of all the actors who are involved in the field of research, healthcare and the treatment of patients”.

Obadia underlined that, “the board of governors is composed of 17 members. The five founding members, including the Mérieux foundation [‘institut’], two teaching researchers, and ten qualified figures”. Among those ten “qualified figures” is former French health minister and cardiologist Philippe Douste-Blazy, who in media interviews recently publicly called for the widespread use of chloroquine to counter the Covid-19 virus epidemic.

Meanwhile, Mediapart questioned pharma giant Sanofi about the 50,000 euros it had provided to the foundation, which was described as “remunerations”. The company replied that this was in the context of a “research partnership” which it said was made during the establishment of the IHU in 2015.

In reality, the IHU was established in 2012, following a contract established that year with the French national research institute, the ANR. SANOFI offered no comment on the confusion of dates, but insisted that “this partnership did not allow for putting in place new therapeutic solutions”, adding that, “We therefore ceased collaboration with the IHU Méditerranée in 2015”.

Meanwhile, the foundation run by Didier Raoult told Mediapart that the sum donated by Sanofi was 150,000 euros and not 50,000 euros, without any explanation of why the 50,000-euro sum appears on the French health ministry site.

Another funder of the foundation is Ceva, a large French animal health products company based in the town of Libourne, south-west France. In December 2017, Civa, which is currently involved in research into the Covid-19 virus, gave 144,000 euros to the foundation. “This concerns doctoral grants funded by Civa,” said Yolande Obadia. “As with all contracts signed with an industrialist, we are obviously subject to a strict clause of confidentiality.”

In his own legally-required declaration of interest on the French health ministry’s database, published on March 19th, Professor Raoult did not detail the funding he received from Japan’s Hitachi Group, nor the value of hthe shares he holds in eight start-up companies. The latter benefit from the know-how and equipment of the laboratory, and as a result agree to give 5% of their capital to the IHU.

One of these start-ups is Pocramé, cofounded by Dr Pierre-Yves Levy, a biologist with Raoult’s IHU, along with businessman Éric Chevalier, and which creates and markets mobile tracking software for laboratories which can rapidly calculate a contagion of infections. On the foundation’s website, this is presented as being among “the products emanating from the IHU” for “the rapid syndromic diagnostic and de-localised of acute infections and their differential diagnostics”.

Contacted by Mediapart, Éric Chevalier commented: “The headquarters of the company is in Aubagne [near Marseille] but we are hosted by the foundation of Professor Didier Raoult. We work with his teams to validate a test that allows rapid detection of the current coronavirus. We believe we can offer this to our clients, among whom are the cruise company Ponant and the shipping fleet operator CMA-CGM, between now and the end of April.”

Didier Raoult did not respond to Mediapart’s request for comment about his stake in the company Procramé.

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse