Ever since the Chinese authorities officially announced the first cases at the start of January, the Covid-19 coronavirus – sometimes known as the SARS-CoV-2 virus – epidemic has continued to spread. As of today there have been some 487,434 cases and 22,026 deaths in 198 countries. As a result scientists have been in a race against time to find a vaccine and, in the meantime, effective treatments for the disease.

But at the same time there have been warnings about rushed judgements and misplaced optimism when it comes to finding quick treatments for the virus. “I am worried that science may end up overpromising on what can be delivered in response to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19),” Holden Thorp, editor-in-chief of Science magazine, wrote in his editorial on March 23rd. Thorp, a chemist, expressed his concern that some scientists and also some drugs might raise false hopes, leading to the risk of “depleting drugs needed to treat diseases for which they are approved”.

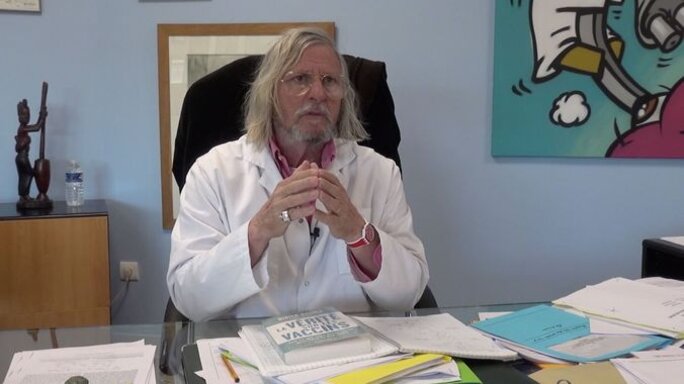

This is because when faced with the urgency of epidemics scientists often start their search for a treatment by looking at existing medicines which have already been used successfully for other diseases and conditions. An example is the drug chloroquine, which has been touted in China, the United States and France as a possible treatment for the coronavirus after declarations made by French expert Professor Didier Raoult, director of the infectious diseases unit at the IHU teaching hospital in Marseille and a member of France's Covid-19 scientific committee, a committee he quit on Tuesday March 24th.

Chloroquine has been effective both in the prevention and treatment of malaria. But it was first used 70 years ago and in some regions of the world it is regarded as ineffective because of resistance built up by the parasitic infection. Today it is also used for the treatment of auto-immune illnesses such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, and also to prevent sun allergies.

Initially this drug did not appear in the World Health Organisation's (WHO) list of priority recommended treatments, nor in the clinical trials – known as 'Discovery' – that have been launched in France. This was because of the drug's side effects – it is also not recommended for pregnant or breastfeeding women – and the potential for adverse reactions with other medicines being used to treat patents in intensive care.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Chloroquine is what is known as a broad-spectrum antiviral compound that can increase a cell's pH values – making it more alkaline – and thus help to block infection from the pH-dependent virus. It has already been tested in a laboratory where it has shown itself to be effective in blocking infection from different viruses, such as the flu, dengue and the chikungunya virus. But it has not shown itself to be effective in live tests on animals and humans.

In laboratory tests it was also shown to be effective against the SARS virus of 2002-2003 and the MERS virus that has hit the Middle East since 2012. But its effectiveness has only been seen in the labs, and it is not known whether it works on people.

On February 4th, close to a month after the authorities there announced an epidemic, Chinese scientists published a letter in the journal Cell Research. They stated that chloroquine, as well as another antiviral drug remdesivir, effectively blocked the new Covid-19 virus in test-tube trials.

These scientists concluded that these two drugs should be “be assessed in human patients suffering from the novel coronavirus disease”. They pointed out that one of the advantages of chloroquine was that it was “widely distributed in the whole body, including lung, after oral administration” and also that it is a “cheap and a safe drug”.

After this letter around 15 clinical trials were carried out in China to test the effectiveness of both chloroquine and the related hydroxychloroquine in patients infected with Covid-19. Then on February 19th a letter was submitted to the journal BioScience Trends. In it a team led by scientist Jianjun Gao from the School of Pharmacy at Qingdao University in China stated that the results of tests on more than one hundred patients showed that chloroquine had shown “efficacy” against “COVID-19 associated pneumonia”. But the letter gave no figures or details of the trial protocols.

Even the WHO is still waiting for the results of these trials. According to the minutes of a meeting of experts who met on March 13th to discuss chloroquine, the organisation said it was working with China but that no data from the study had been shared with it thus far.

Back on January 27th the WHO had been of the view that there was “insufficient evidence to support chloroquine’s further investigation”. As a result the drug had not appeared in the list of priority medicines to be tested for use against Covid-19. It was only added after enthusiasm for the drug was expressed by a number of countries, including France, after the declarations made by Professor Raoult.

Those declarations came just over a month ago, on February 25th, when Professor Raoult surprised public opinion and the scientific community with a video initially called “Coronavirus: end game!” and then subsequently entitled “Coronavirus: towards an end of the crisis?” in which he highlighted the results of the Chinese scientists.

A few days later, on March 4th, Professor Raoult's team published an article in the International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents in which they described chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as “available weapons to fight COVID-19”. The authors explained why these two drugs were their first choices for treating patients with the virus. They summarised the results of the laboratory tests by the Chinese scientists and the outcomes of the first clinical trials. They also justified their decision based on their knowledge of the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine, a drug they had used for thirty years to treat patients with bacterial infections such as Q fever and Whipple's disease.

On March 5th their proposal to carry out clinical trials was approved by the regulatory body the Agence Nationale de Sécurité du Médicament (ANSM) and on March 6th by the Paris regional health authority the ARS Ile-de-France. The trial started using Plaquénil, the hydroxychloroquine brand name produced by pharmaceutical firm Sanofi, who subsequently offered to provide a million doses to treat 300,000 people following the initial results from Professor Raoult's team published on March 16th.

Criticism within the scientific community

Hydroxychloroquine is a derivative of chloroquine. The two drugs work in the same way but hydroxychloroquine appears to be the safer option as an effective dose of it is lower down the toxic scale than an effective dose of chloroquine. It was also more effective against the Covid-19 virus in laboratory tests.

The trial carried out by Professor Raoult's team was “open” and “non-randomized”. This means the doctors knew who was and was not treated, and the decision to treat was not carried out randomly as is the the case in standard clinical trials. Sixteen patients were used as a control, in Marseille and other hospitals in the south-west of France, including Nice.

Though a total of 26 patients were treated with hydroxychloroquine, the results only relate to 20 of them. Three others were taken to intensive care, one died, one stopped treatment because of the nausea it caused and one left hospital – and they may not even have had the virus, as it was not detected in a test.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The fact that the results of these six patients was not taken into account has caused something of a stir in the scientific and medical community. Karine Lacombe, head of the infectious and tropical disease unit at the Saint-Antoine hospital in Paris, said it was a huge mistake. “When a patient goes into intensive care or dies you are obliged to say that it's a failure in treatment.” She added: “Rather than say that their treatment failed, they were removed from the analysis. You can't do that.”

The 20 sick people who stayed in the study all received hydroxychloroquine, with a dose of 200mg three times a day for ten days. Six were also given an antibiotic, azithromycin, in order to prevent the risk of a bacterial infection. By the sixth day 14 of the 20 had “recovered from the virus”, against 12.5% from the control group (2 out of the 16). And 100% of the six patients who were given a combination of hydroxychloroquine and antibiotics recovered as opposed to 57.1% of those who were just given hydroxychloroquine and the 12.5% in the control group.

In the 'discussion' section of their paper the authors themselves acknowledge that their study has certain limits “including a small sample size, limited long-term outcome follow-up, and dropout of six patients from the study”. But they add that “in the current context, we believe that our results should be shared with the scientific community.”

However, so far while the results have been passed on, the raw data has not. The epidemiologist Philippe Ravaud, who is director of the research centre the Centre de Recherche Épidémiologie et Statistique (CRESS), has asked for them but had still not received them when Mediapart spoke to him and he criticised Professor Raoult for not having shared the data. “Nowhere in the world can one accept data of such importance not being shared,” said the epidemiologist. “The basis of scientific trust is that the data produced by one team can be replicated by other teams, in particular through redoing the analysis.”

Professor Didier Raoult is a big name on the world scientific stage. But that has not stopped several people questioning his communications and his scientific protocols, for example on Pubpeer, which is an online forum where scientists can comment on scientific publications.

The epidemiologist and bio-statistician Dominique Costagliola, who has been authorised by France's Covid-19 scientific committee to analyse this trial, is also very critical. “This study has been conducted, described and analysed in a non-rigorous way, containing impressions and ambiguities,” she told Le Monde on March 24th. “It's a study that is at a high risk of bias according to international standards. In this context it is therefore impossible to interpret the effect described as being attributable to treatment by hydroxychloroquine.”

As a result scientists are awaiting the outcome of the Discovery national clinical trial. Though it had initially been excluded, hydroxychloroquine has now become the fifth strand of treatment in this trial which is being carried out on 3,200 ill people in Europe, 800 of them in France.

The trial started on Sunday March 22nd at the Bichat hospital in Paris and the main teaching hospital in Lyon in eastern France. Once again it involves using existing medicines for new purposes. The first group will receive standard care and serve as a control. The patients in the second group will be given remdesivir, an antiviral drug initially developed against the Ebola virus. The third group will be treated with lopinavir-ritonavir, a combination medicine used to treat HIV. The fourth group will get the same plus interferon beta-1a, which is used to treat patients with multiple sclerosis. The fifth group will be given just hydroxychloroquine.

In addition to the trials carried out by Didier Raoult, hydroxychloroquine has already been trialled in some hospitals in France, in Lille in the north of the country and also at the Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital in Paris, before the start of the Discovery trial. Alexandre Bleibtreu, a specialist in infectious diseases at Pitié-Salpêtrière, told Mediapart that his unit used hydroxychloroquine on around 40 patients, even though he had earlier criticised the Marseille study. “We are trying it because some new information has reached us,” he said. “With the rise in the number of cases, with deaths every day, we had to do something.”

His unit had previously tried, without success, the lopinavir-ritonavir combination. “There's also a form of pragmatism and empathy towards our patients,” said Alexandre Bleibtreu. “We're trying to choose the strategies that seem to us to have the most favourable benefit-risk balance for our patients.” The results of this compassionate rather than clinical trial are being analysed and should be available within a few days.

*On Thursday March 26th, after the publication of this article, health minister Olivier Véran decreed that hydroxychloroquine could be prescribed in hospitals, if the doctor thinks it will be useful, even though the clinical trials have not yet been completed.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter