The Covid-19 coronavirus epidemic in France is accelerating towards a peak, which the head of the intensive care unit at one of the major Paris hospitals, Ambroise Paré, on Friday forecast would occur at the beginning of April.

The history of the epidemics in other countries demonstrates that when that peak nears, the numbers of cases will escalate suddenly and sharply. Hospital staff around France are in a state of anticipation – the exception being those in the north-east Alsace region where they are already overwhelmed by the outbreak, and where the army was last week called in to erect an emergency field hospital and to evacuate patients by helicopter to other parts of the country.

“We know that it will be a tidal wave,” said Gérald Delarue, an anaesthetics specialist nurse with the public emergency medical aid service, the SAMU, attached to a major hospital in Lille, northern France. “There is anxiety, because there will be deaths, but there is also a lot of strength. We have done a lot of thinking, [and] work, to put into place an extraordinary, novel organisation.”

Writing on his blog on Mediapart last Thursday, neurosurgeon Laurent Thines, based in the eastern French town of Besançon, evoked the moment before a tsunami, when the sea retreats before the giant wave strikes. He described a “calm” among his colleagues, “like in the hospital corridors where an unworldly, surrealist, deserted atmosphere reigns”, adding that the “calm” includes his agenda for operations over the past fortnight.

“We have divided in half our surgical activities, we only now take charge of emergencies,” he added. “The ventilators in our operating blocks have been taken to arm the new intensive care beds in our observation wards. We now have a capacity of 120 beds.”

Until now, the international experience is that around 80% of people infected by the Covid-19 virus show practically no symptoms, while 15% will develop severe illness, often in the form of pneumonia. But what the hospitals are gearing up for is the emergency care for the remaining 5% who slip into a critical condition, one that often develops very rapidly, sometimes in a matter of just hours, with acute respiratory distress and organ failure. These patients are placed on artificial respiration, sedated, intubated and put into an artificial coma.

Jean-Michel Constantin, an anaesthetist at the Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital in Paris predicted a first wave of patients would arrive over the weekend. He described the preparations of the Paris public hospitals management body, the ‘Assistance publique-Hôpitaux de Paris’ (AP-HP), the largest of its kind in France with 39 establishments under its control. “Our strategy is to protect, for the moment, our intensive care capacity,” he said. “We are sending patients to private clinics so that their teams have training. Of the 1,000 intensive care beds of the ‘Assistance publique-Hôpitaux de Paris’, 600 are dedicated to Covid [-19 coronavirus] patients.”

A report in French daily Libération on Thursday cited the AP-HP as announcing that 227 of those beds were by then already occupied. Constantin said that if all the public and private healthcare sector was mobilised across the Greater Paris Region (with a population, in 2019, of 12.12 million), around 2,000 intensive care beds could be created.

A nurse with the anaesthetics team of the intensive care unit of a hospital in Avignon, south-east France, who asked for his name to be withheld, recounted the re-organisation in preparation for the expected sudden arrivals: “We had 14 intensive care beds, [now] we have 35. To manage that, we brought together all the available resources – [facial] respirators, ventilators, syringe pumps, beds, anti-bedsore mattresses.” He said there was a “total” mobilisation of personnel, with all holiday leave postponed. “Operating theatre nurses have joined intensive care,” he explained. “Nurses who left the service to work elsewhere have returned of their own will. Young retirees also come to reinforce us.” He said that while there is anger over the lack of resources in the healthcare system, and which has been notably the subject of widespread protests by medical staff over the past year, that issue was now “secondary”.

In the southern town of Perpignan, close to the border with Spain, one member of staff of the local hospital’s intensive care unit spoke to Mediapart on condition his name was withheld. For the purpose of this report he has been given the pseudonym of Laurent. He lamented that, “it is certain that if hospitals had more staff it could have changed the situation”, adding: “The problem with our profession is that it is never the right time to raise union demands. Here it’s not the time because it’s going to be a war.”

Laurent spoke of his concern that there was no testing of medical staff for Covid-19 infection. “They refuse to screen us, they say that there aren’t enough [devices for] tests,” he said. He also denounced the lack of personal protection equipment, notably FFP2 facial masks. “Normally, regarding patients kept in isolation, we should wear a hermetic overall, gloves, a mobcap, a FFP2 mask, and when we leave the [patient’s] room we throw everything away. Today, we’re asked to keep our FFP2 masks for the [officially] valid [useage] time [Editor’s note: three to four hours]. But when we look after a patient we receive droplets on the mask, then we’ll go an telephone with it, come and go in the unit. There, we’re really putting ourselves in danger, because of economic concerns.”

He said the healthcare staff felt abandoned by their management, who he said did not appear to understand their situation and even added to their workload. “Because the cleaning staff don’t come into the service anymore, it’s down to the auxiliary nurses, on top of their daily tasks, to do the cleaning,” he said, as an example. “But we have contaminated patients and we must clean more often, and more intensely.” He added that couriers were no longer allowed to take blood samples to outside laboratories even though the packages were decontaminated and presented no risk. “Decisions are taken by people who don’t understand what we’re living,” he said.

The Perpignan hospital services administration did not respond to Mediapart’s attempts to reach it for comment.

- Will intensive care facilities be able to cope?

In relative terms, the number of intensive care beds in France per 100,000 people (around 11.6 according to 2012 figures) is significantly below that in Germany and the US, but sits in overall average place among European countries, and higher than in Britain or Spain.

Speaking last Tuesday, Jérôme Salomon, head of France’s Directorate General of Health (the health ministry’s healthcare policy planning and application agency) announced that the country had increased the number of its intensive care beds nationwide from 5,000 to 7,000. “Two thousand are available,” he said, “and we have at our disposal around 10,000 machines – respirators and ventilators.”

By Saturday evening, 1,525 people with Covid-19 infection were receiving life support in intensive care in France.

Some epidemiologists in France predict a vast rise in the numbers of patients needing intensive care. In an interview with French daily Le Monde published on Friday, Pascal Crépey, who teaches epidemiology and biostatistics at the School of Public Health Studies in Rennes, north-west France, warned: “Between March 10th and April 14th, the number of serious cases could climb to 40,000 across the whole of France, and the number of deaths to more than 11,000 in one month.”

That speculation was met with stoicism by Jean-Michel Constantin, anaesthetist at the Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital in Paris. “Epidemiologists say lots of things,” he said. “Forty-thousand serious cases in France? We don’t know how, but we’ll deal with it.”

- A looming choice about who will live, and who will die

Hospitals in France are readying themselves for the dilemma of having to filter patients, as is the case in Italy, in the event of a saturation of intensive care services.

A dedicated working group of experts, commissioned by the government, studied the issue and delivered its report on March 17th, entitled “Prioritisation of access to crucial care in the context of a pandemic”. The report notably recommends prioritising patients according to a “fragility score” which takes into account their underlying health situation and the specific dangers of the Covid-19 virus.

Other official documents, seen by Mediapart, avoid directly addressing the issue. But some hospitals, like that in Perpignan, clearly set out their plans in black and white. In an internal document, obtained by Mediapart, sent to Perpignan hospital’s healthcare staff on March 18th, a “five-stage” plan on the prioritisation of patients is set out: “If the number of critically ill is superior to SSE [exceptional sanitary situation] or catastrophe situation resources, a selection will have to be made.”

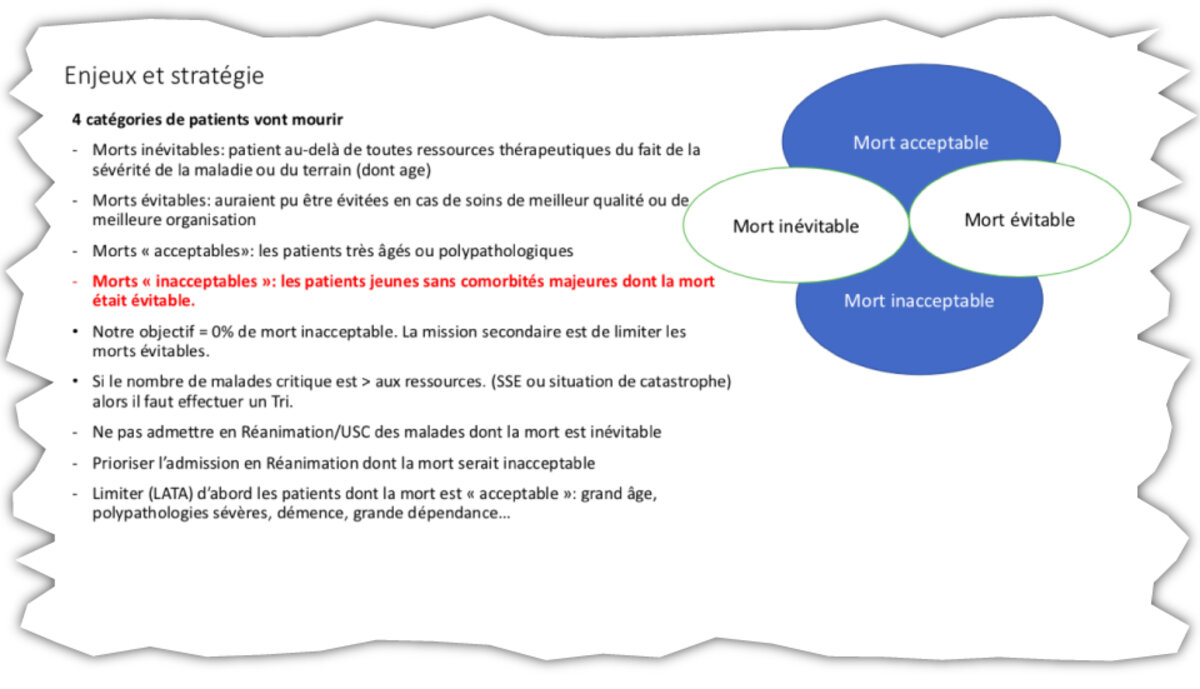

The document (see below) warns “four categories of patients will die”, detailing these as: “Inevitable deaths: a patient beyond all therapeutic resources owing to the severity of the illness or terrain (including age). Avoidable deaths: could have been avoided in the case of care of a better quality or better organisation. ‘Acceptable’ deaths: very elderly or polypathological patients. ‘Unacceptable’ deaths: young patients without major comorbidities whose death was avoidable.”

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The target set is “0% of unacceptable deaths” while “the secondary mission is to limit avoidable deaths”. The plan for a situation of forced selection is to not admit patients “whose death is inevitable” into intensive care and to prioritise those “whose death is unacceptable”, and to limit or halt active treatment firstly in the case of patients who death is “acceptable”, which the document cites as those being of “great age”, those with “severe polypathologies, dementia, major dependency”.

'It is a very, very hard situation'

The Perpignan hospital document is based on the projection of a 16-week epidemic, and uses two models for the surrounding Pyrénées-Orientales département (county) and a part of the neighbouring Aude département, a combined area which together totals 631,000 people. One of these is an “optimistic” hypothesis whereby the infection rate is “only 30% of the population”, and the other is a “realistic” hypothesis of a 60% infection rate which it notes is “the current estimations of experts”. In the latter case, 1,735 patients in a critical condition would be admitted into care, “representing an average rate of 108 critical patients per week during 16 weeks” – compared with 60 per week in the former example.

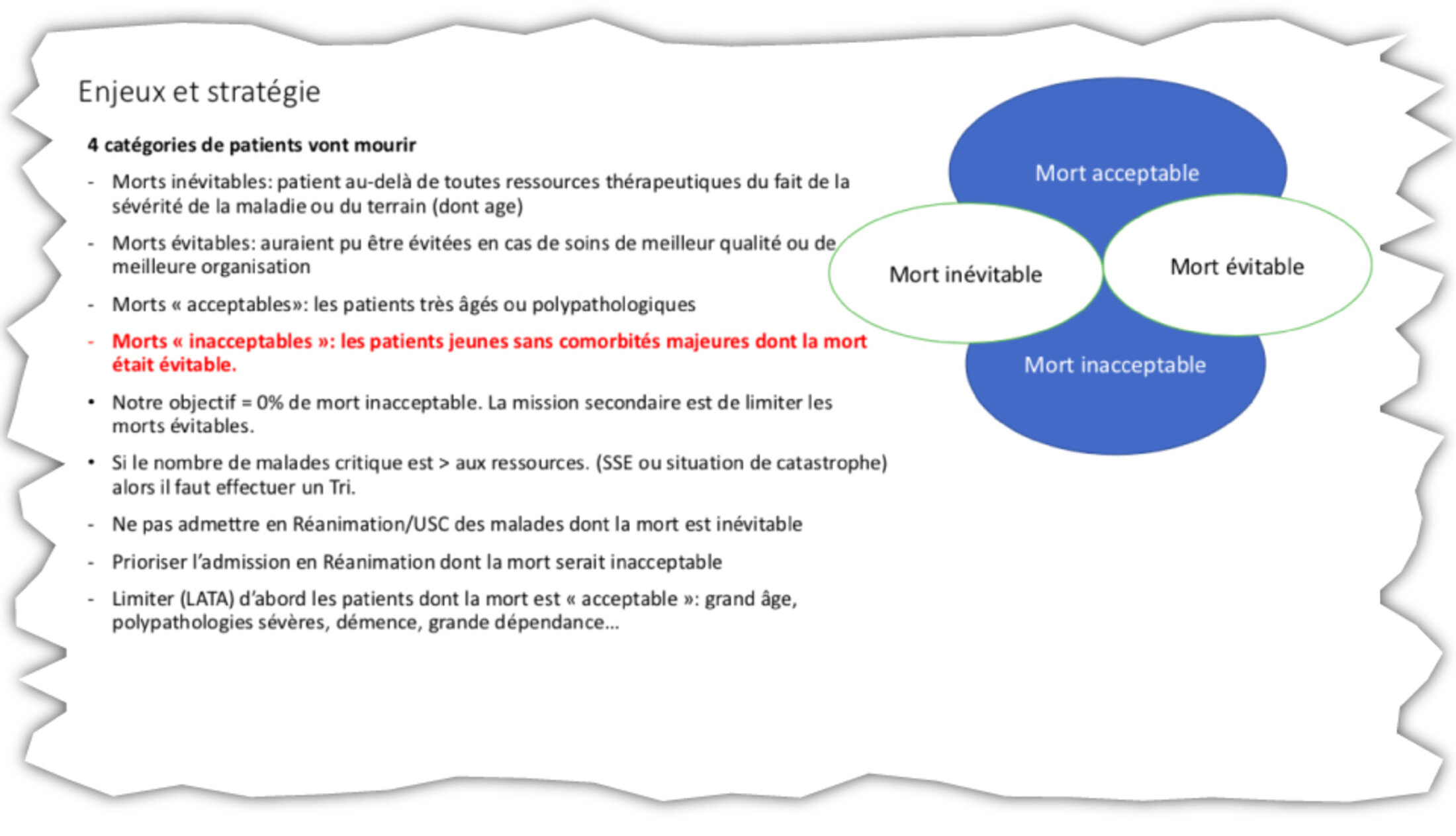

The plan allows for five successive stages according to “the severity and duration of the crisis”. The hospital is currently at Stage 3, which is described as one of “tension”, while the fifth stage is one that is “out of control” and involves “catastrophe” healthcare (see document below).

Enlargement : Illustration 2

“The doctor who drew up this plan told us that ‘we will get to stage five in Perpignan’,” said the member of staff of the hospital’s intensive care unit, cited further above under the pseudonym of Laurent. “I hope he’s got it wrong.”

“We are aware that we’ll reach this stage of selection [of patients],” he added. “We know that it’s going to be difficult. One of our doctors is in contact with a doctor in Italy who warned him they’re piling up corpses in the churches. It’s a hecatomb, we have to prepare.”

“In normal times we already have criteria, patients who are considered unsavable as of a certain age, when one is no longer admitted into intensive care, and so on. But to make a selection as of 70-years-old, as is reportedly the case currently in [the eastern French town of] Mulhouse, that we haven’t experienced, it’s a baptism of fire. At the moment, all our Covid patients who entered intensive care aged more than 80 have died.”

Laurent said he and his colleagues were particularly concerned about the prospects of a widespread contamination of the Covid-19 virus among the gypsy community in Perpignan, who live in often squalid conditions in the town’s Saint-Jacques neighbourhood, statisticallyone of the poorest in France. “Around 90% of Covid patients in intensive care [at the hospital in Perpignan] come from the gypsy community,” he said. “It is a population at risk because they are often obese, smokers, diabetic, and sometimes as of a young age. Most of them live at Saint-Jacques in very close quarters and in poverty.” Laurent said he feared there would be “a large inflow of youngsters”, and a situation whereby it would be necessary “to make choices earlier and quicker”.

“It’s going to be very complicated,” he added. “We’re really worried that we’re going to be overwhelmed.”

Meanwhile, at a major hospital in a town in eastern France (which is unnamed here to protect the identity of the interviewee), there is, according to a nurse attached to a unit treating Covid-19 patients, a selection, unspoken of in public, of those admitted for treatment. “It’s not said, because it is unsayable, but the tacit advice is to no longer admit to hospital those aged over 75, to leave them in the EPHAD [care establishment for the elderly and dependent] or at home. That’s to say, to let them die.”

The nurse said that there are ever fewer intensive care beds available and that masks are running out. He is particularly struck by the profiles of those being treated for covid-19 infection: “Many young people, aged between 40 and 60, and numerous healthcare workers including a leading figure at the hospital who was on the front line.” He said the hospital staff felt real fear. “Despite all the experience that we have, in difficult services like intensive care, palliative care, we are not trained for this, a warlike problematic, choosing patients, those we are not going to take into care, to accept to see people leave alone to death, in solitude without people close, in plastic bags, without any ritual for families.”

He said staff unions have requested from the hospital management a rapid provision of psychological help for the personnel. “One must expect there will be syndromes and post-traumatic neuroses, like in wartime, for us who are already exhausted, demoralised,” he warned.

- Ethical dilemmas already a reality in the Alsace region

At the main hospital in the town of Colmar, in the Alsace region of eastern France, the head of the Accident & Emergency (A&E) service, Yannick Gottwalles, last week explained that the staff had prepared ahead for the Covid-19 outbreak, which rapidly spiralled earlier this month from a cluster into an epidemic, but had no idea what was to come. “We de-programmed everything that wasn’t urgent, found personnel reinforcements, reorganised our emergency units, spread our intensive care beds, created dedicated Covid zones,” he explained. But, when the sudden tidal wave of the epidemic came, he said “all the decisions taken, and the arrangements, became obsolete, overtaken in the 12 hours that followed”.

“We are prepared for serious accidents, which place tensions of a short duration, or an epidemic, but with a regular curve,” Gottwalles added. “But not for that.” He warned that with what he described as a doubling of numbers of critically ill patients each day, “it will be necessary to make choices concerning our criteria for admissions, not only to intensive care but quite simply to the hospital structure”.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

In the nearby town of Mulhouse on Thursday, Frédéric Pernot, head of the SAMU medical emergency services for the surrounding Haut-Rhin département, declared a total saturation of intensive care units in his area. “When you intubate a 70-year-old person,and they take up the last available bed, we are anxious that we [may] see a 50-year-old person turn up one hour later in respiratory distress,” he said.

The French army is now helping the crisis in Alsace, notably with transportation of patients to hospitals outside the region and by building a field hospital which will provide an extra 30 beds. “But for how long will intensive care services accessible by helicopter be able to receive our patients?” asked Pernot.

Sandra (not her real name), a nurse with the A&E services at Mulhouse hospital, said she wanted to speak anonymously because “the hospital bans us from talking to the media”. She described the prioritisation of patients: “We ask ourselves the question about a therapeutic limitation for all people aged more than 70, according to their state of health. Elderly people infected with Covid in EHPAD [care homes] are no longer taken to hospital. We limit ourselves to giving them comfort care, to ease pain. It’s very difficult, we’re not here to choose who should live and who should die.”

“In our daily work, we might decide to halt treatment, to avoid aggressive therapeutics,” she said. “But it is much less frequent, and is done with taking time to talk about it, between medical staff and with the family.”

“The Covis patients are not allowed to have visits,” Sandra explained. “When we put them to sleep to intubate them and palce them in intensive care, they’re not sure to wake up, and they are alone. It’s very difficult.”

In another hospital in Alsace, a doctor told Mediapart that she was not yet confronted with the dilemma of patient selection, but that she is concerned over a looming situation where decisions may have to be taken to remove a patient from intubation, because of the shortage of ventilators. “We are not yet in this situation because here we are just at the beginning, but it is a situation which we anticipate, as it is currently the case in Italy,” she said. “Covid demands prolonged periods of intubation, 14 days per patient on average. That’s long, and it mobilises ventilators over all the period. In Italy, the first young patient was intubated for four weeks.”

She said it would be down to the ethics committee to pronounce on decisions about removing people from intubation. “We ask ourselves, ‘Will that patient there hold on or not ?’ ‘Do we de-intubate them?’ Obviously, we never take such a decision alone. The teams talk together. Here, the ethical committee is made up of three doctors. It is a very, very hard situation. It’s also the story of our lives, of becoming enhardened so as not to suffer. But everyone suffers, even the heads of services. They’ve never lived through this 'wartime' medical situation.”

-------------------------

- This is a slightly abridged version of the original report in French, available here.

English version by Graham Tearse