Historically speaking, anti-war sentiment is relatively recent. Before 1800 wars were depicted as grandiose naval or land battles in scenes peopled by mythological heroes or those who were carving out a place in the history books. The characters embodied the kind of strength that is revealed in the thick of battle, whether on the side of the victor or the conquered. There is violence, but the individuals remain glorious, the crowds are ready for action and the battlefields are majestic.

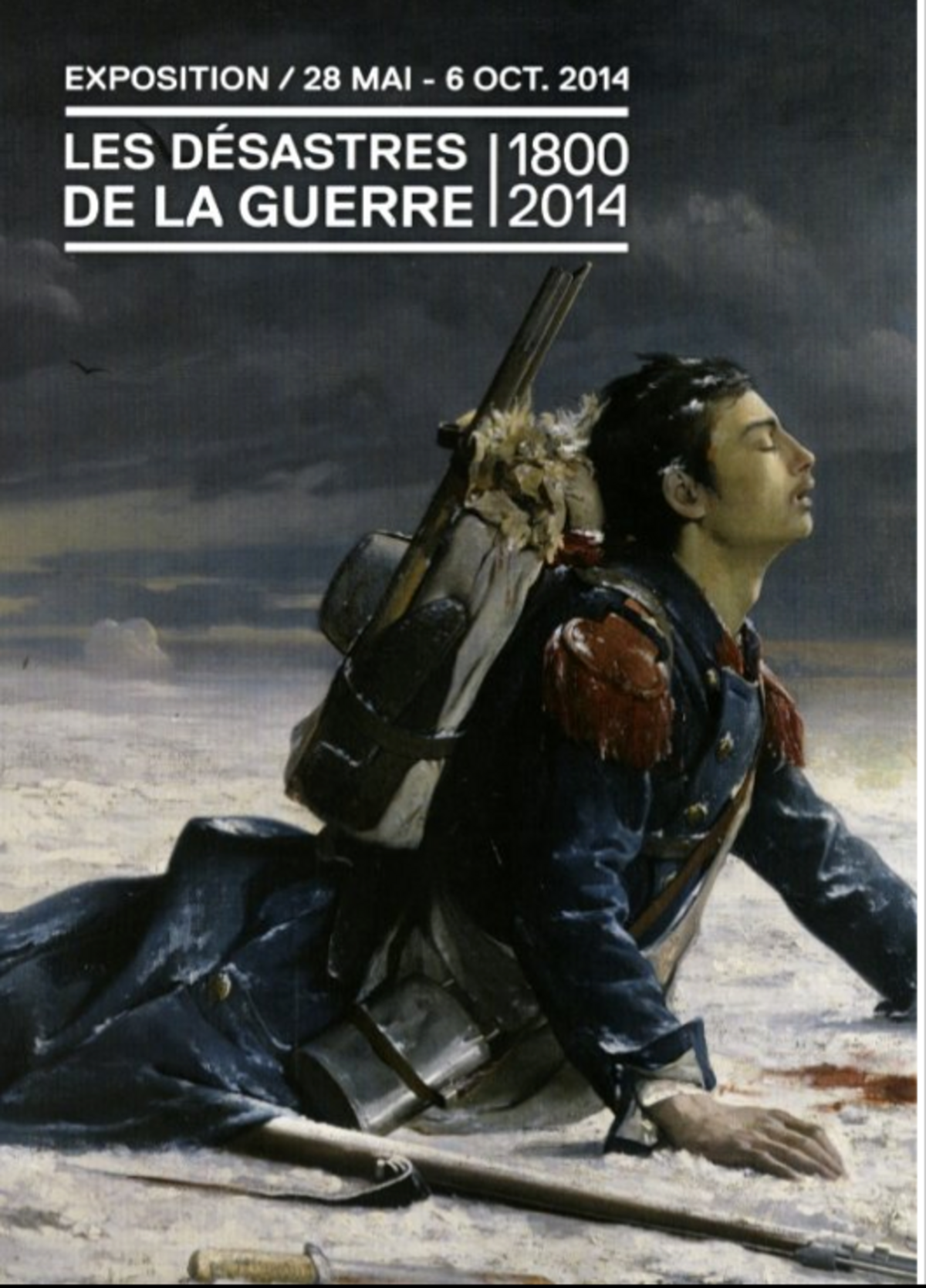

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The exhibition Les Désastres de la Guerre, 1800-2014 (The Disasters of War, 1800-2014), now showing at the Louvre-Lens - the Louvre museum’s annexe in Lens, north-east France - starts at the point in time when things began to change, at the end of the 18th century and in the early 19th century. Instead of painting heroic war scenes that reflected the values of earlier societies, artists had then begun to represent the disastrous consequences of war on humans, animals, nature, towns, material things, psychology, and on the whole of humanity.

One of major strengths of the exhibition, which lasts until October 6th, is that it illustrates, in the words of the show’s curator Laurence Bertrand Dorléac, how "each war constitutes a visual turning point”. Changes in imagination, politics and military or artistic techniques - for example with the emergence of photography - produce novel representations of war.

The first major shake-up in the way armed conflicts were depicted came with the Napoleonic Wars and painters like Géricault and Goya. These pioneering artists broke with the tradition of heroics and began to portray war in a radically new way. Instead of just painting allegorical and symbolic figures, they gave a place to the flesh-and-blood individuals with whom wars are waged.

The second significant feature of this exhibition is that it is structured not as a succession of chefs-d'œuvre but over a (long) period of time, which allows some connections to emerge between the wars themselves, connections that come from artists' own perceptions. This accounts for the exhibition's chronological arrangement, but within that there are circuits in which works from different periods that bear a relationship to each other are brought together.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

This creates a striking sensorial impact. Contemporary Chinese painter Yan Pei-Ming reinterprets Goya's famous Tres de Mayo (Third of May) with a wash of red paint that looks like blood. Bertrand Dorléac sees Yan's painting as influenced by the bloody repression of the pro-democracy movement in Beijing's Tiananmen Square in 1989. "The painter refers to the old masters, but adds his own history," she said.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

In another example of counter-posing works, the exhibition screens a film made by Georges Mélièsin1897 that is a direct reference to the painting by classical artist Adolphe de Neuville in 1873, Les Dernières Cartouches(The Last Rounds). A quarter of a century after Neuville's painting, Méliès builds on what could be anachronistically called the cinematographic movement in this painting, bringing it to life with the animated image, the then brand-new technique for representing reality

The possibility of making these connections between works is what prompted the Louvre-Lens to venture with this exhibition beyond its usual timeline of between Antiquity to the mid-19th century, said Xavier Dectot, the museum’s director. The Louvre-Lens is also a natural choice given its location in the north of France, where the disasters wrought by war have been massive. Their traces still remain in the region’s topography.

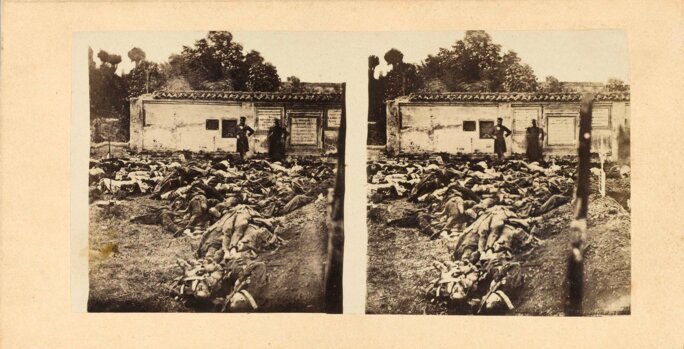

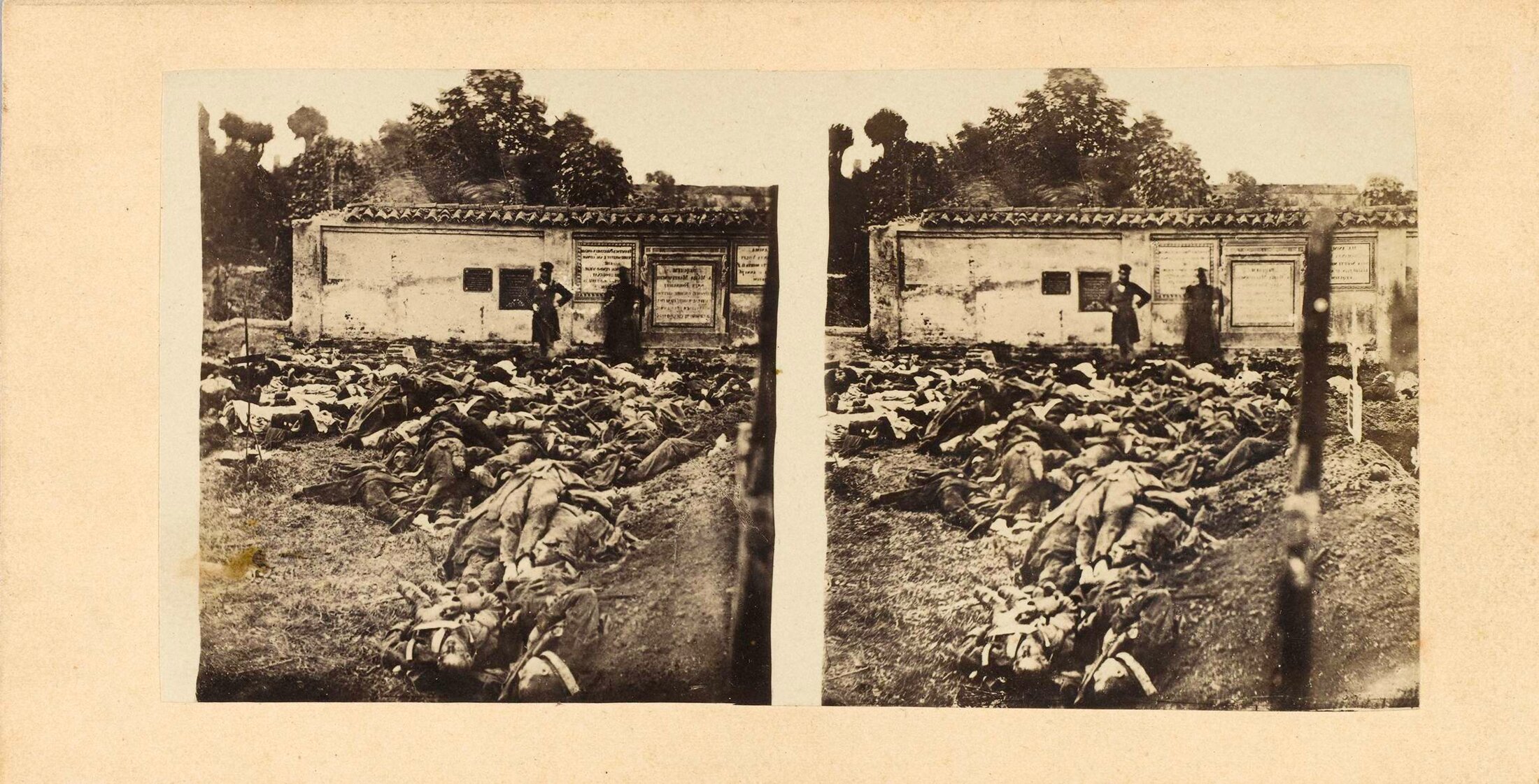

Enlargement : Illustration 4

At the entrance to the exhibition, a film shot in 1918 from a hot-air balloon shows the ravaged landscape of the front line at Lens. It is almost a premonition in black and white of the devastated palm trees in French war photographer Sophie Ristelhueber's colour photos from the Iraqi desert in 1991.

Official images give way to mud and blood

Then the exhibition's itinerary takes you through 12 sequences that follow the chronology of wars begun in the West and sometimes exported elsewhere. Amid the predictable references, like Picasso's preparatory work on Guernica, or Robert Capa's photographs on the Spanish Civil War, for example, there is always something unexpected in each sequence.

Those depicting the colonial wars include drawings by Fauvist Kees Van Dongen when he was an anarchist, drawings that translate both the violence of the British wars against the Boers in South Africa and the Boers' own oppression of the black population.

The exhibition also shows the first photograph of war dead, often thought to date from the American Civil War. In fact it was taken in Italy in 1859, by Jules Couppier. There is also a series of etchings done in 1924 by Otto Dix, Der Krieg (War), in which sheer horror serves as a convulsive catharsis to the silences and taboos of the period following World War 1.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

Also worth noting is a previously unseen extract from a restored first version of the film J’accuse by Abel Gance, dating from just after WW1. In it, the dead rise from the trenches where they fell and return to hold the living to account. The atmosphere is the purple of hallucinations, and there is a daring superimposition of takes in a single image – the troops marching under the Arc de Triomphe in Paris are superimposed on the corpses marching like zombies.

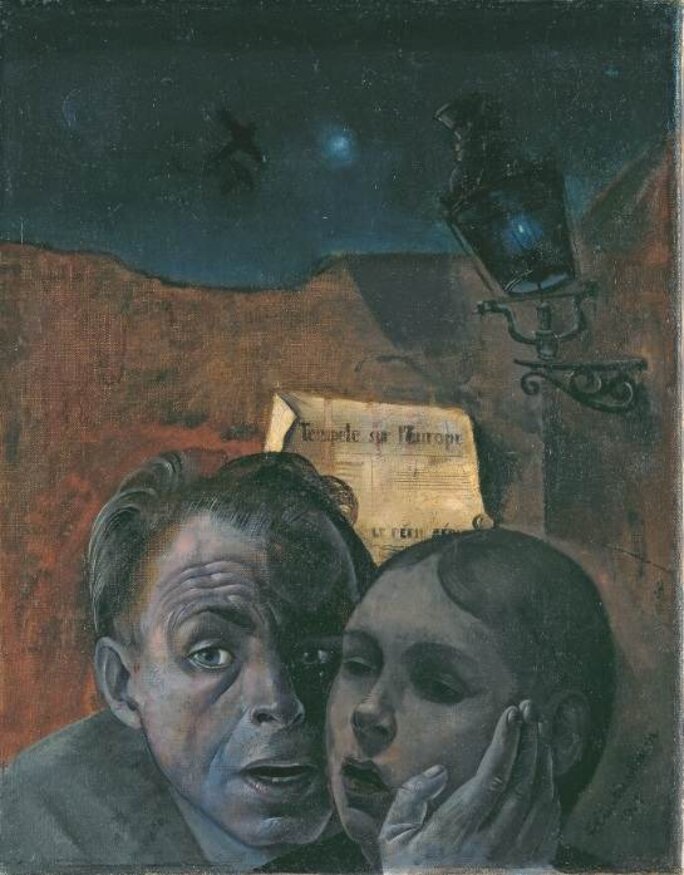

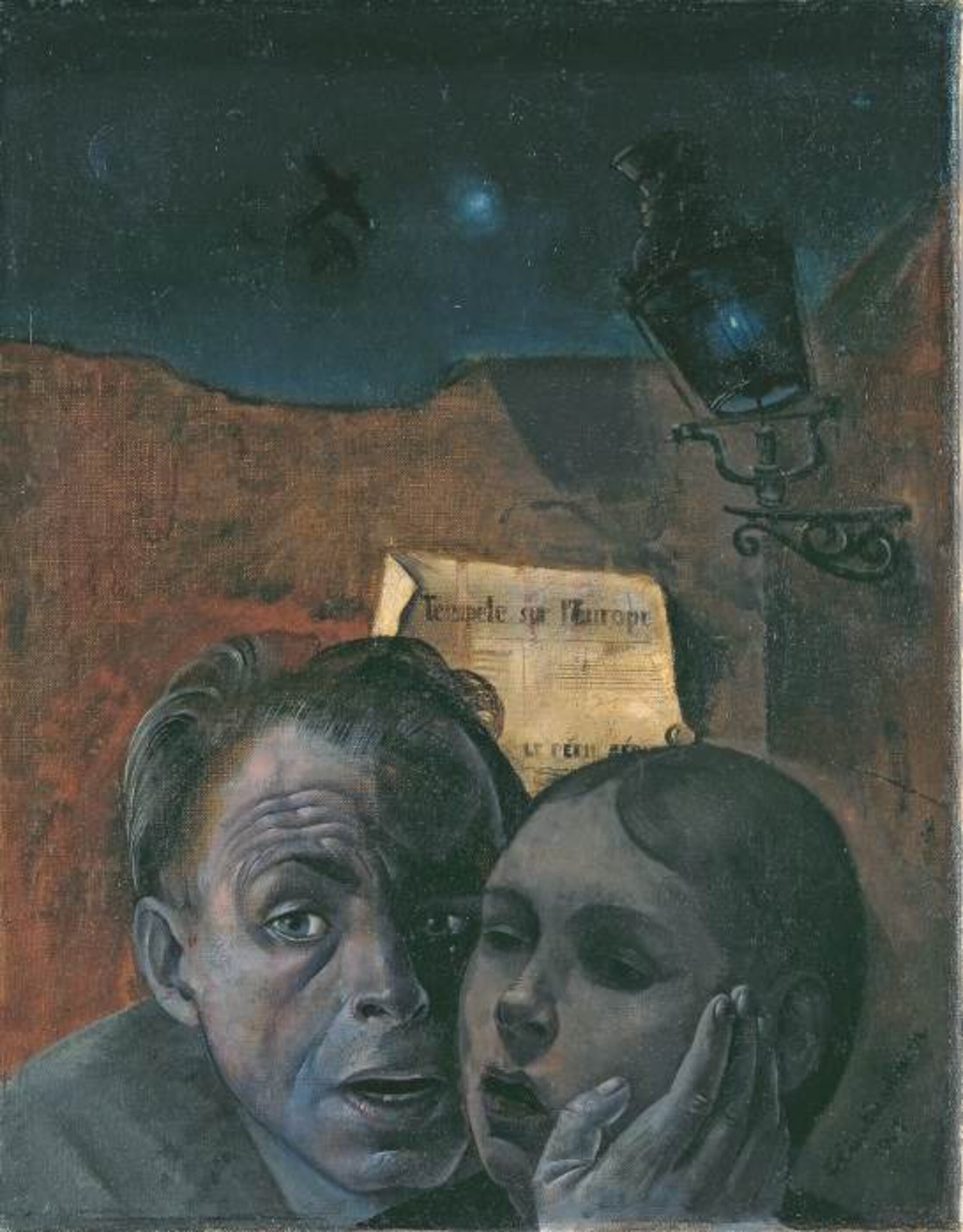

Enlargement : Illustration 6

One of the most intense works in the exhibition is a painting by Felix Nussbaum, Peur (Fear), which opens the sequence on the Holocaust. It is a self-portrait with his niece Marianne, painted just before he was deported to Auschwitz – like an ultimate record of his life on earth, says Bertrand Dorléac. Also in this section is The Nazi Plan, a rarely screened film on the concentration camps by George Stevens that was commissioned by the American military for use at the Nuremberg Trials. Bertrand-Dorléac decided that it should be shown in this context.

The exhibition also highlights times when the official image could not hold before the realities of war and the singularity of the suffering, and ultimately slips to reveal the mud and blood when the commanders wanted to show only heroes. An example of this is a painting by Horace Vernet, who was an official painter and propagandist for colonisation.

Vernet's Combat de Somah portrays an episode in the siege of Constantine by the French, but Bertrand Dorléac says he miscalculated its effect. "The French troops look stupefied and stupid, particularly next to the figures of the Arab fighters,” she said. “In fact, it is about an unsaid aspect of that war. The French soldiers were drunk. And Vernet unintentionally reveals what was officially unsaid."

Enlargement : Illustration 7

Similarly, during the Crimean War from 1853 to 1856, when press photography reached the battlefields for the first time, photographer Roger Fenton was sent by the British government with instructions not to show the dead or wounded. He obeyed his orders, but his photographs, which turn the bleak landscape itself into the focus, underline the violence and destruction of war just as clearly as corpses would.

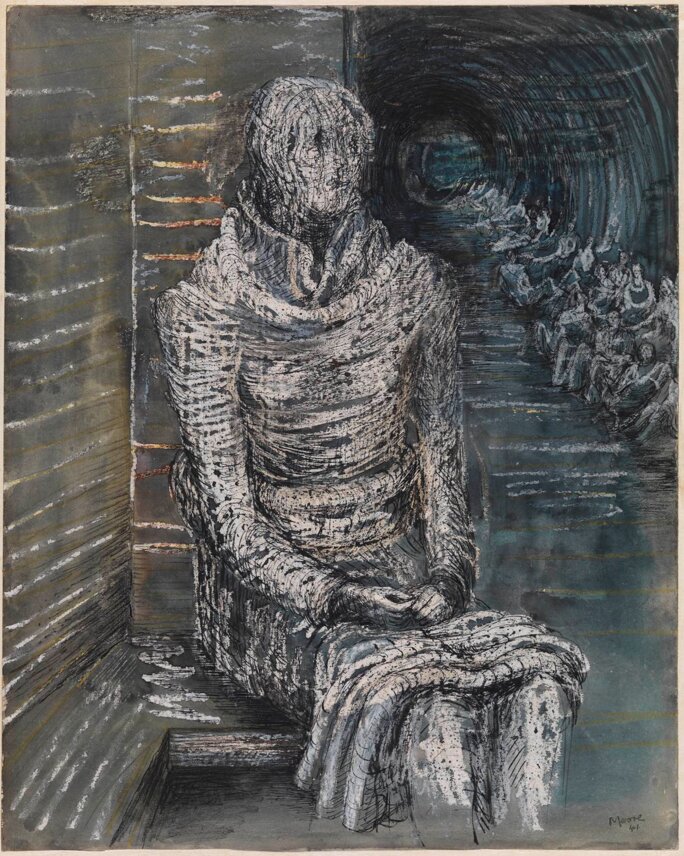

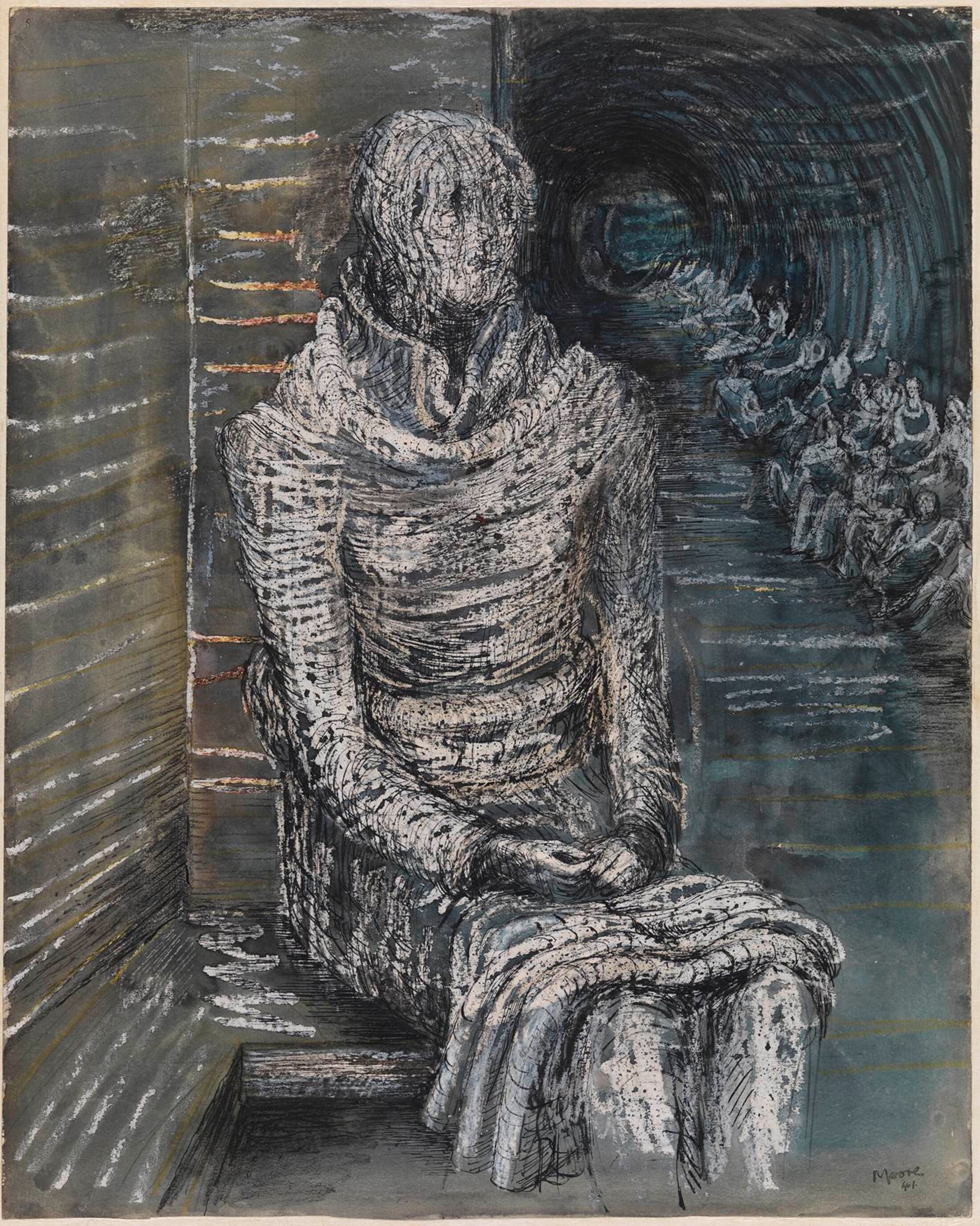

A century later, Henry Moore was commissioned by the British government to record the effect of the Blitz on London and show how the Nazi regime was attacking courageous civilians. But the effect of his work was different. He unrelentingly portrayed how the human condition was reduced to animal level in London’s bomb shelters and Tube stations.

Enlargement : Illustration 8

Bertrand Dorléac writes in the exhibition catalogue that the title of the exhibition, taken from a Goya series that is also exhibited in Lens, may appear to be consensual because it is easy to "regret the fatal consequences of a conflict with hindsight". But "our supposed universal disgust" for the destruction caused by wars is deceptive, she cautions.

It is indeed still possible not to really see wars despite the thousands of images we are exposed to, while war has certainly not lost its ability to fascinate and excite, despite the changes in the way it is depicted. As the French biologist and writer Jean Rostand once said: "Kill one man, and you are a murderer. Kill millions of men, and you are a conqueror. Kill them all, and you are a god."

-------------------------

- The exhibition Les Désastres de la Guerre, 1800-2014 (The Disasters of War, 1800-2014) is on now and until October 6th at the Louvre-Lens (for more information click here).

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Sue Landau

(Editing by Graham Tearse)