Judges Renaud Van Ruymbeke and Roger Le Loir last year signed off their two-year investigation into the hidden foreign assets of former French finance minister Jérôme Cahuzac, when they brought charges of money laundering and tax evasion against Cahuzac, his former wife Patricia, and the bankers, wealth manager and an intermediary who handled the secret accounts that were first opened in Switzerland and later transferred to Singapore.

The ten-day trial, which is due to open in Paris on February 8th, will also hear the additional charge against Jérôme Cahuzac, 63, that he hid part of his assets from the mandatory declaration of his wealth when he entered President François Hollande’s first government in May 2012.

The judicial investigation led by judges Van Ruymbeke and Le Loir was opened after Mediapart revealed how Cahuzac, who as finance minister had launched a crackdown on tax evasion, had for 20 years held a secret bank account abroad.

Mediapart’s initial revelations were published in December 2012, and met with firm and public denials from Cahuzac, including before parliament. Supported by his government colleagues, and notably then-economy minister Pierre Moscovici, Cahuzac finally confessed to holding the account on April 2nd 2013, five months after Mediapart's first revelations and one week after Van Ruymbeke and Le Loir had begun their judicial investigation.

That judicial investigation was completed in June last year. In a 28-page document summing up the evidence for sending Cahuzac and his six co-defendants for trial, the magistrates detail how the former minister’s secret account was, as first revealed by Mediapart, mostly funded by pharmaceutical companies he acted as an advisor to, and how, contrary to his claims – after confessing to its existence - that it had been dormant for 20 years, it served to pay for trips to the Seychelles and Mauritius islands between 2004 and 2007, and for cash withdrawals in 2010 and 2011.

The withdrawals included deliveries of cash to him in Paris, when he was president of the French parliament’s finance commission between 2010 and 2012.

The document, dated June 17th 2015, until now confidential and reproduced in full immediately below, reveals that he also, between 1997 and 2007, held an account based in the Isle of Man together with his former wife Patricia, who was at the time his business associate in the couple’s private hair transplant clinic.

Just one week after the opening of the judicial investigation, the magistrates received a written confession from Cahuzac who had been forced to step down as minister because of the probe: “Contrary to the declarations that I was led to make while I was a member of government,” it read, “I am the holder of an account abroad and wish to provide you with every explanation on this subject.”

Interestingly, in the careful wording of the note, Cahuzac did not write of declarations “that I made” but rather “that I was led to make”. In a book about the affair by Jean-Luc Barré to be published in France at the end of January, entitled Dissimulations and which Mediapart has obtained an advance copy of, Cahuzac tells the author: “I would not have lied as I did if I hadn’t felt covered.” But the book, which implies more than it informs, does not say who Cahuzac felt covered by.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The judicial investigation identifies the first foreign bank account held by Cahuzac as being that which was opened on November 26th 1992 with the UBS bank in Switzerland, with the account number 556405. At the time, Cahuzac had recently left his position as a member of health minister Claude Evin’s senior staff, during the socialist government of prime minister Michel Rocard. During his period at the ministry, between 1988 and 1991, Cahuzac developed ambiguous ties with the pharmaceutical industry.

The account with UBS was opened by Philippe Péninque, a far-right militant with close ties to both Cahuzac and the Front National party leader Jean-Marie Le Pen and his daughter and successor Marine Le Pen. Questioned by the magistrates leading the investigation, Péninque insisted that he had “only” served to open the account. Péninque has not been charged.

The first movements on the account were a deposit of 285,000 French francs (the currency then in circulation, a sum equivalent to 43, 447 euros), followed soon after by a withdrawal of 125,240 French francs (equivalent to 19,000 euros). “This double operation invalidates the statements of Monsieur Cahuzac according to which he had deposited cash,” write the magistrates in their conclusions. “It is exactly the opposite that happened: the account is credited by bank transfer then followed by a cash withdrawal.”

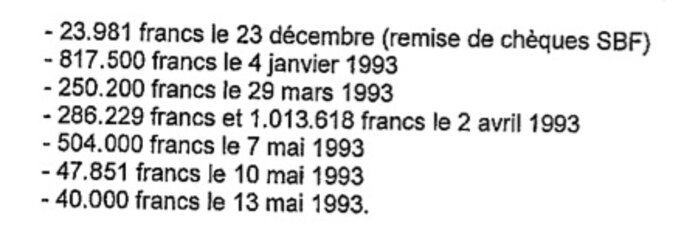

According to the findings of the magistrates, the account received vast deposits between December 1992 and May 1993 (see list below).

The magistrates noted that, contrary to what Cahuzac and his lawyers had publicly maintained, he “confirmed having received secret remunerations not linked to his activity as a doctor – the amounts are far too high – but to his activity as advisor to laboratories [pharmaceutical firms].”

“He benefitted from easy access to, and good contacts with, the [health] ministry, thanks to his previous functions in the ministerial cabinet,” they continued. “The stakes were high for the laboratories [pharmaceutical firms] which wanted to market medicines with the assurance that they would be given a reimbursable status with the social security system.”

Under questioning, Cahuzac said that two of the deposits on his Swiss account made in January and May 1993 and which totalled 1,321,500 French francs (201,460 euros) may have been payments from drugs firm Pfizer. “Monsieur Cahuzac has given no explanation about the origins of the other deposits, other than indicating that he worked for other laboratories such as Pierre Fabre, Roche, Sandoz, UPSA,” wrote the magistrates.

Jérôme Cahuzac, alias 'Birdie'

In his book Dissimulations, Jean-Luc Barré insinuates – without clearly stating – that Cahuzac’s hidden account may have been intended to serve as a secret funding source for Michel Rocard, socialist prime minister between 1988 and 1991, when Rocard was planning to stand in the 1995 presidential elections (which in the end he never took part in).

“Does the former collaborator of Claude Evin look after his own interests here or does he act under orders, in the framework of a financial mission that had been secretly given to him?”asks Barré. “Deliberately or otherwise, Jérôme Cahuzac leaves the door open to every supposition. The theory of a warchest secretly built up by Rocard’s camp, like those of other political groups, would not be unbelievable. When Jérôme Cahuzac is questioned [about this] he begins with an amused silence.”

A second account was opened by Cahuzac with UBS in Geneva in 1993. Baptised “Birdie”, the account (number 557847) replaced the first and was managed by the small private Swiss banking firm Reyl & Cie. Wealth manager Hervé Drefus served as the intermediary between Cahuzac and the bank, noted the magistrates, who were told by Cahuzac that when he wanted to make cash deposits or withdrawals from his Swiss account he would call a designated phone number. “I had a phone number,” he explained, “I’d call, I identified myself as Birdie.” After which a cash withdrawal would be made on his behalf.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Cahuzac’s relationship with Reyl & Cie - whose directors have been charged alongside Cahuzac for money laundering – became so close that by 1998, when he was a Member of Parliament for a constituency in the Lot-et-Garonne département (county) of south-west France, he would transfer secret payments exclusively via the Geneva firm. On October 3rd 2000, Reyl & Cie wrote to Cahuzac to advise him that he should cease operations on his account if his “political situation was to evolve”. Indeed, Cahuzac ‘s political career was then promising, and he became one of the campaign management team for outgoing socialist prime minister Lionel Jospin in his 2002 presidential election bid. In the event, Jospin suffered a humiliating defeat and Cahuzac lost his parliamentary seat in general elections shortly after.

Between 2000 and 2001, at least 200,000 French francs (30,490 euros) were credited to Cahuzac’s Swiss account, the magistrates noted. Questioned about the new sums, Cahuzac told the magistrates that he sometimes worked abroad where payments by check were not frequent. “I didn’t want to bring these cash sums back to France because I would have been required to declare them to customs,” he explained in a statement. “So I’d call the number I was given with Reyl. Someone would present themselves in the country I found myself in to whom I gave the cash.”

In 2003, 106,715 euros were sent from Cahuzac’s account to an account with the Migros bank in the name of a company called PMT Systems SA. According to an internal document from Reyl & Cie, the transfer concerned “the purchase of a painting”. However, Cahuzac told the magistrates that it was sent to someone who had given him an advance payment for an “investment” in France.

In 2004, his secret account was used to pay for holidays in the Mauritius islands (18,000 euros). In 2006, it was used to repay 92,000 euros via the Rothschild bank regarding a secret loan Cahuzac had received. In 2007, it was again used to pay for Cahuzac’s holiday spending, this time in the Seychelles islands (6,000 euros).

In 2009, when Switzerland began cooperating with international investigations into moneylaundering and tax evasion, Reyl provided a number of its clients with new ways of hiding their assets. For Cahuzac, this involved transferring what he had in his Swiss account to a firm in Panama, called Penderly, from where it would be again transferred to an account in Singapore with the Julius Baer bank. This was opened in the name of a Seychelles-registered company, Cerman Limited. When Chauzac was finally forced, in April 2013, to confess owning the account, it held a total of 687,076 euros.

“The Reyl bank made known to me that as of the moment that my wish for discretion stayed the same, the [initial] structure couldn’t remain in place,” Cahuzac told the magistrates. “They told me that I was a depositor who the bank particularly wanted to protect and that the evolutions taking place, and to come, urged them to offer me different and more precautious management methods. In the first instance, they explained to me that I should pass through a Panamanian structure. That left me puzzled but I went along with it. In a second instance, it was they who explained to me that they had put into place a very discreet [system of] organization of which the ultimate end was Singapore. At no time did I suggest either this place or the means of getting there. I did not have the required technical knowledge for that. I signed what they gave me to sign.”

However, when the bank’s chairman, François Reyl, was questioned by the magistrates in the presence of Cahuzac, the banker said it was Cahuzac who asked for “increased confidentiality and a distancing from Switzerland”. Reyl described the Swiss bank’s transfer of Cahuzac’s assets to Singapore as a “perfectly transparent operation”, adding that “opacity signifies hiding a client, we simply reinforced the confidentiality”.

What the magistrates described as a “sophisticated” structure with Singapore included the services of a Dubai-based French lawyer close to Reyl, Philippe Houman. “Its complexity shows that the banker knew the process very well, which he has used for other clients,” wrote the magistrates. “[…] The transfer was purely virtual. By a series of book entries, Monsieur Cahuzac was the beneficiary of the reinforced protection presented by the Singapore market place, while retaining the same correspondent, his Swiss bank in which he had confidence.”

For Cahuzac, the operation of his account remained the same as when it was in Geneva. In 2010 and 2011 he used the call sign “Birdie” to demand deliveries of cash totalling 20,800 euros. The amounts were brought to him in Paris by a special envoy.

In their June 2015 report, the magistrates, in the somewhat awkward style of such judicial documents, conclude: “This delivery of cash illustrates the know-how and endurance of a system offering a client, in 2011, services that constitute acts of money laundering: the delivery of cash in Paris, on a street, via the debiting of an account opened in the name of an exotic company in Singapore on the basis of a phone call from a client hidden by a pseudonym (“Birdie”), a delivery carried out on the orders of a former lawyer residing in Dubai who has access to the debited account, all of which is punctuated by the visit of a Reyl employee to a bank in Geneva to withdraw money from the Geneva bank whose subsidiary holds the account in Singapore.”

The magistrates also detail how, in 1997 when Cahuzac became a Member of Parliament for the first time, he and his then-wife Patricia created a company in London called Ellendale, established via an account based in the tax haven of the Isle of Man. The couple also opened a joint account with the Bank of Scotland, of which Patricia Cahuzac became the sole holder in 2007. Cahuzac admitted the existence of the Isle of Man account to the magistrates, but claimed he never became involved in its management. After it was made known to the investigation, in July 2013, Patricia Cahuzac transferred 3 million euros from it back to France.

Finally, the magistrates record that Cahuzac placed earnings from his and his wife’s hair transplant clinic, undeclared to the tax authorities, on his mother’s bank account. The total of these, between 2003 and 2010, amounted to 214,000 euros. The magistrates noted that, when when questioned about the matter, Cahuzac “did not provide satisfactory explanations”.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse