Nicolas Sarkozy had been given six weeks to prepare for his questioning last week by anti-corruption police investigating evidence that his 2007 presidential election campaign was funded in part by the regime of late Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi.

But the former French head of state was on several occasions unable to convincingly answer questions put to him, according to transcripts seen by Mediapart and cited below, and on several occasions appeared to place the responsibility for a number of compromising relationships and events surrounding his dealings with the Libyan dictatorship, established by the investigation, on his close staff.

Under questioning, Sarkozy, 63, presented the same force in his denials of wrongdoing as that which he demonstrated during his appearance in a live television interview last Thursday, when he appeared to tremble with indignation at the implication that he had been secretly sponsored by a foreign power. But in the substance of what he said to police, and later before the judges who subsequently placed him under investigation, he appeared wrong-footed by numerous questions, when he presented a version of events that suggested any criminal relations with the Gaddafi regime occurred without his knowledge.

Sarkozy was informed on February 7th of his summons to appear in March before officers of the anti-corruption and financial crime police agency OCLCIFF at their headquarters in the suburb of Nanterre, west of Paris, when he was also offered a choice of dates for the appointment.

The questioning began on Tuesday March 20th at 8am, when he was placed in police custody, at the beginning of six separate sessions of questioning over the following 32 hours when, in an unusually clement move for such a procedure, he was allowed to return home overnight. He was finally notified at 4.37pm on Wednesday by the three magistrates in charge of the investigation, judges Serge Tournaire, Aude Buresi and Clément Herbo, that he was to be formally placed under investigation for “illicit funding of an electoral campaign”, “receiving and embezzling public funds” from Libya, and “passive corruption”.

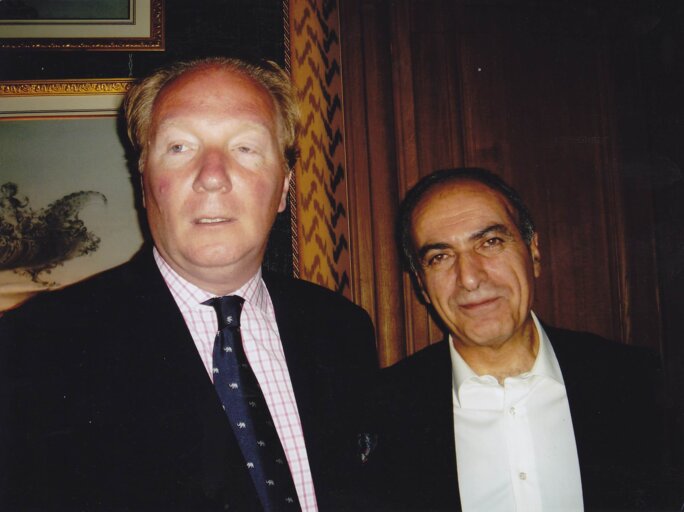

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Under French law, to be “placed under investigation” requires that magistrates have found serious and/or concordant evidence that indicates a person has committed an offence, the gravest of two forms of indictments that have now replaced in France what were previously “charges”.

Sarkozy was also placed under “judicial control”, a restrictive measure broadly equivalent to conditions of bail. The move was requested by the special financial crime division of the public prosecution services, the PNF, although the precise details of the judicial control finally decided upon by the three judges leading the probe, who have ultimate decision on the matter, is not known. The PNF asked for Sarkozy to be prohibited from contacting a number of people cited in the case, and also from travelling to Libya, Tunisia, Egypt, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and South Africa.

The people the PNF requested Sarkozy to be barred from entering into contact with are his longstanding political allies Claude Guéant and Brice Hortefeux (the latter was also questioned by officers from OCLCIFF last Tuesday); French-Lebanese businessman and intermediary Ziad Takieddine, French-Algerian businessman Alexandre Djouhri (currently held in London awaiting extradition to France); Bashir Saleh, the former head of Gaddafi’s 40-billion-dollar Libyan African Portfolio (LAP) sovereign wealth investment fund and the dictator’s chief of staff, now exiled in South Africa; the former head of the Gaddafi regime’s foreign intelligence service, Moussa Koussa; former French intelligence services chief Bernard Squarcini; Sarkozy’s former wife Cécilia Ciganer-Attias; former French ambassador to Iraq and Tunisia, Boris Boillon; former French prime minister Dominique de Villepin, and also Michel Scarbonchi, a businessman and former Member of the European Parliament (MEP).

At the start of his questioning last Tuesday, Nicolas Sarkozy asked for it to be recorded that he contested “the necessity of being placed in custody”, and denounced “a vulgar manipulation of unequalled proportions and which had the consequence of making me lose the presidential election in 2012 […] and the [conservative party Les Républicains] primaries” held in November 2016 to choose the conservatives’ candidate for the 2017 presidential elections.

“It is not in my habit, but I want to express the force of my anger and the profound degree of my indignation,” the former president continued. “Seven years that I’ve been pursued on the basis of statements by rogues, convicts and assassins,” added Sarkozy, whose manner of speaking is often clipped.

He was particularly scathing of Ziad Takieddine, the Paris based businessman and intermediary of Lebanese origin who over several years acted as a key intermediary in introducing Sarkozy and his close political team to the Gaddafi regime, as well as to the authorities in other Arab countries. Takieddine has also been placed under investigation in the case after he admitted carrying in 2006 and 2007 a total of 5 million euros in cash provided by Libya to both Sarkozy, then interior minister, and his chief of staff Claude Guéant, who is also placed under investigation in the probe. After his initial denials of involvement, Takieddine, who Sarkozy told investigators was “a liar and madman”, has become a prominent witness in the case.

During his final questioning by the three magistrates last Wednesday, Sarkozy was asked: You have made very negative appreciations of Ziad Takieddine. But documents discovered in the framework of another case tend to demonstrate that he played a role in negotiations between France and Libya in the context of your visits to Libya as interior minister, and then as president of the [French] republic. He was notably in contact with Claude Guéant and Brice Hortefeux. One can find it difficult to imagine that you were unaware of these elements.”

Sarkozy’s response was to throw the ball into the court of Guéant and Hortefeux, even compromising the position of his longstanding and loyal allies. “That Brice Hortefeux could have frequented him [Takieddine] on a personal basis, that’s his decision,” said Sarkozy, whose 40-year friendship with Hortefeux included appointing him a s interior minister during Sarkozy’s presidency. As for Claude Guéant, who he also appointed as interior minister, at the end of his presidency, after serving as Sarkozy’s chief of staff when the latter held several ministerial posts between 2003 and 2007, and also as Sarkozy’s 2007 election campaign manager, the former president told the magistrates: “I don’t know when, and how many times [Ziad Takieddine] has seen Mr Guéant, he [CG] will explain himself.”

“I am certainly the person who has the least met with Mr Takieddine […] It is true that I am responsible for what I have done, and if ever Brice Hortefeux or Claude Guéant said ‘It’s Nicolas Sarkozy who asked it of us’ you can consider that that is my responsibility. But that’s not true, they never said that,” Sarkozy continued. Such comments at one point prompted the magistrates to point out to Sarkozy that the dealings of Guéant and Hortefeux were “in the framework of their responsibilities and when they were under your hierarchical authority.”

Enlargement : Illustration 2

During the police interview, Sarkozy said he had personally met Ziad Takieddine just twice: once in 2002, when they were introduced by the late Gaullist conservative figure Philippe Séguin, a former president (speaker) of parliament’s lower house, the National Assembly, and then, in 2003, when Sarkozy was interior minister, at the ministry. Their meeting then was to discuss a weapons contract with Saudi Arabia. As Mediapart has previously revealed, for his role as intermediary in securing the contract, codenamed “Miksa”, Takieddine was promised a commission of 350 million euros.

During their investigations, the police seized as evidence a number of documents which clearly prove that Takieddine was involved in the Saudi contract negotiations alongside Claude Guéant. “I learn from you the existence of these notes and I knew nothing of them,” commented Sarkozy, who insisted that Brice Hortefeux, who was at the time one of interior minister Sarkozy’s close staff, had “never” been involved in the negotiations.

But last Tuesday, when Hortefeux was also questioned by police although not placed in custody, he declared: “The Saudi authorities made it known that they wished to meet the entourage of the Minister of the Interior – his principal collaborator, his chief of staff and a person close to him, more precisely, me. Something which, it was explained to me, was usual practice.”

The negotiations led by Sarkozy’s team was suspected as being a means for the then-interior minister to begin, through a syphoning off of commission payments, to establish funds for his bid to run in the 2007 elections. At the time, Sarkozy was an arch rival within the conservative UMP party to then-president Jacques Chirac, whose close team succeeded in putting an abrupt end to the looming deal with the Saudis. The current judicial investigation appears to have established that it was as a result of the scuppering of the contract that Sarkozy’s entourage, still with the hope of building up a war chest for 2007, turned their attentions to Libya, again using the services of Ziad Takieddine as intermediary.

Earlier in the judicial investigation, a former French foreign ministry translator was questioned by police. She told them that, “after verification” of her records, she had accompanied Sarkozy on a total of three visits to Libya. Two of these were when he was interior minister, and the third when he had become French president. However, in all, Sarkozy was invited to make just two official visits to Libya. Questioned in turn about this last week, Sarkozy said: “To my knowledge, I have found no trace of a third trip, but if not let me be told at what date and in which circumstance and I might revise my position.”

Meanwhile, earlier in the investigation Claude Guéant gave a statement about the important role played by Ziad Takieddine in the Sarkozy team’s dealings with Libya between 2005 and 2007. “Honestly, he [Takieddine] played a role because he was in frequent contact with Gaddafi’s brother-in-law, who was called Abdullah Senussi and, from time to time, he gave me the ‘temperature’, the climate on the Libyan side,” said Guéant, while denying involvement in any illicit funding. Abdullah Senussi, who is now being held in a Libyan prison, was Gaddafi’s internal security chief, who in 1999 was given a life sentence 'in absentia' in France for organising the bombing of a French airliner that crashed over Niger in 1989 leaving 170 people dead, including 54 French nationals. His name was also cited in the investigations into the December 1988 bombing of a Pan Am airliner which exploded above the town of Lockerbie in Scotland, killing 270 people.

When Nicolas Sarkozy was confronted with Guéant’s statement last week, he insisted: “Never did Claude Guéant inform me of his contacts with Takieddine.” It was a surprising comment given that Guéant was at the time his closest member of staff, and officially his chief of staff at the interior ministry.

Sarkozy was also asked his opinion about a document written by Takieddine about the preparations he was making for a visit by Guéant to Tripoli in September 2005. In his notes, Takieddine underlined the need for a certain discretion by Guéant when bringing up “the other important subject, in the most direct manner” with the Libyan regime. “What was this subject concerned with, so important that it required so much discretion?” the former president was asked, to which he replied that he did not know.

'Guéant didn’t inform me'

Sarkozy did however recall that when he first met Gaddafi, during a trip to Libya on October 6th 2005, Gaddafi had spoken to him about the legal situation of Abdullah Senussi who, following the ‘in absentia’ sentence of life imprisonment handed to him by a French court in 1999, was the subject of an international arrest warrant.

One month after Sarkozy’s first visit to Tripoli in October 2005, an exchange of fax messages shows that his personal lawyer and longstanding friend, Thierry Herzog, was contacted to represent Senussi’s interests and to attempt to overturn the international arrest warrant issued in his name. “Yes, this gentleman [Senussi] tried to contact a lawyer who is close to me […] This Mr Senussi tried by every means to benefit from the skilled services of Thierry Herzog,” Sarkozy told the police last week, but insisted that the mandate given to Herzog was “thrown in the bin”.

But other evidence demonstrates that up until at least 2009, attempts were made to overturn the international arrest warrant against Senussi by a lawyer close to Herzog. According to the records of Ziad Takieddine and seized by police, a meeting on the subject was held at the French presidential offices, the Elysée Palace, in May 2009.

Senussi represents a further problem for Sarkozy in that both Takieddine and Senussi himself have confirmed that the latter organised the transfer to France, between the end of 2006 and the beginning of 2007, of a total of 5 million euros in cash to fund Sarkozy’s 2007 election campaign. According to their accounts, it was Takieddine who personally carried the amounts back to France. Sarkozy was told last week by police that evidence demonstrated that “Ziad Takieddine did in fact make the journeys that he mentioned in his statements about the delivery of cash sums”. Sarkozy replied: The question is not to know if Takieddine is in Libya. The question is to know whether he gave me money, that’s not the same thing after all.”

Enlargement : Illustration 3

In his statements, Sarkozy described Takieddine as being “profoundly unbalanced”.

While the former president has insisted that he has never met Senussi, that is not the case of his longstanding close political ally and friend Brice Hortefeux. In December 2005, Hortefeux made a trip to Tripoli in his capacity as the then-French Minister for Local Authorities. The incongruity of a local government minister making an official trip to Gadaffi-run Libya was summed up by the then-French ambassador to Libya, Jean-Luc Sibiude, who later said the visit had “little sense”. During his own questioning by police last week, Hortefeux admitted meeting Senussi in the presence of Ziad Takieddine. The meeting was held without the presence of ambassador Sibiude, without a translator and without the presence of a French security officer. Questioned in turn about the meeting, Sarkozy replied: “I learn it from you. I didn’t know.”

Sarkozy was questioned about Senussi’s claim that, on top of the cash payments, money was also transferred by the regime from the Libyan foreign bank, to which he replied: “If this account exists, it should be easy to find it, to find who it belongs to.” He was then informed by police that they had been able to trace a payment of 2 million euros sent from the Libyan Foreign Bank on November 21st 2006 to an offshore account belonging to a company called Rossfield Trading Limited which belonged to Ziad Takieddine.

“Does this transfer not correspond with Mr Takieddine’s commission for having organised the financial support that you might have benefitted from in the context of the electoral campaign,” the police asked Sarkozy, to which he replied: “That Mr Takieddine had received money from Mr Gaddafi, that’s certain […] There is another thing about which there is no doubt, which is that the relationship between Mr Takieddine and me never existed at any time and at any level: political, financial or as friends.”

The police officers then told Sarkozy that while Takieddine had had “difficulties in explaining himself about this operation of 2 million euros” he had avowed “transporting 5 million euros in cash which he has admitted to having received from Mr Senussi and that he would have deposited in Paris, at the Ministry of the Interior, in the office of Claude Guéant, and in yours. The transport of cash was to have been operated also at the end of 2006 and at the beginning of 2007”. Sarkozy replied: “I believe to have demonstrated the absolute impossibility for Mr Takieddine, like for anyone else, to enter the ministry of the Ministry of the Interior without having a due and proper appointment. As for the rest, the statements of Takieddine are those of an unbalanced person whose credibility is nil.”

Enlargement : Illustration 4

The interrogating police officers then told the former president: “To complete this, during the questioning of Mr Senussi, carried out in Libya in the presence of his lawyer, he declared he had attempted to convince Colonel Gaddafi to finance to the level of 20 million euros [the funds] requested to support your campaign. But ‘the Guide’ [‘of the Revolution’, an unofficial title adopted by Gaddafi] reportedly only accepted [to give] this support to the limit of 7 million. It appears that Mr Takieddine admits to having deposited 5 million in cash, and there is this bank transfer of a supplementary 2 million received by Mr Takieddine, who does not have the habit of working for free. Finally, the statements of Mr. Senussi seem to confirm the material evidence gathered, and this without him being able to know about it [the material evidence], having been detained since several years.”

The police then asked Sarkozy, “What have you to say to these comments?”, to which he replied curtly: “I have no comment to make. This is an association of thugs and criminals.”

When the former president told the police that it was “extravagant that with all this supposed money, all these alleged conveyors, the number of suitcases and [bank] accounts, there is no element which, near or far, connects them to me or my campaign”, he was then asked about an intriguing rental by Claude Guéant of a vault inside a Paris bank, which Guéant rented only for the period of Sarkozy’s 2007 presidential campaign. The vault was rented from a branch of the BNP bank close to the Garnier Opera house in central Paris, and which was large enough for a person to enter at full height. “I didn’t know about this rental before learning about it from the press,” replied Sarkozy.

The police asked Sarkozy why Guéant, who was at the time Sarkozy’s 2007 election campaign director, would have found time to personally make numerous visits to the vault. “For what reasons did Claude Guéant take the time, during so dense a period for him, to visit the vault on seven occasions between March and July 2007?” they asked.

“I have no idea,” replied Sarkozy. “He didn’t inform me.”

During the current investigation, Guéant was asked what the vault was used for, and, denying it was used as a safe for cash deposits, replied that he had rented it to place inside his personal archives and to store Nicolas Sarkozy’s speeches. In contrast, several former campaign team staff have told the investigation that they were certain the vault was used to store cash.

'Mediapart leads a political operation that provokes nausea'

In an earlier summary report of their investigations, the police observed it had been established that during Sarkozy’s 2007 election campaign organisation there was a remarkable circulation of important sums of cash, which had not been declared to the official authorities monitoring election spending – and which was therefore illegal spending. Under recent questioning, Sarkozy’s campaign treasurer, Éric Woerth (who, after Sarkozy’s election was made budget minister, and later labour minister), confirmed the existence of the cash sums used by the campaign team.

Questioned last week about the use of cash during the campaign, Sarkozy again denied any knowledge of the practice. “I have no element to give you on the subject […] Mr Woerth has my every confidence. I am sure that all that is in conformity with the regulations, and for as long as the contrary is not demonstrated to me I maintain my confidence in him,” said the former president.

Bashir Saleh, now exiled in South Africa, was the head of Gaddafi’s 40-billion-dollar Libyan African Portfolio (LAP) sovereign wealth investment fund and also the dictator’s chief of staff. According to witness statements given to the French judicial investigation, when the civil war broke out in Libya in 2011 Saleh put in safekeeping the essential records of the regime’s financing of the Sarkozy campaign. He was smuggled out of war-torn Libya with the help of France’s foreign intelligence agency, the DGSE. Several declassified documents from the agency are now part of the evidence collected by the French investigation.

As president, Sarkozy also had the title of head of the French armed forces, but he told the police last week that he was not aware of how Saleh escaped Libya. “I know nothing of the conditions of the departure from Libya of Bashir Saleh,” he said. When he was notified that one DGSE report noted that Saleh thanked Sarkozy for all the help he had provided, the former president commented: “I don’t remember anymore.”

On April 28th 2012, during the presidential elections when Sarkozy was seeking a second term in office, Mediapart published a document from the Gaddafi regime which detailed its agreement to fund his 2007 campaign. At the time, Saleh was living in France, apparently free in his movements despite being the subject of an Interpol “Red” notice, which requested international police forces to detain him following a warrant issued for his arrest by the post-Gaddafi Libyan authorities. In early May 2012, five days after Mediapart’s revelation of the Gaddafi regime document, the French authorities, with the help of businessman Alexandre Djouhri, a close acquaintance of Sarkozy’s, smuggled Saleh out of the country.

At the time, Claude Guéant was interior minister, having been appointed to the post in 2011 after serving for four years as chief of staff at the presidency. Under questioning last week, Sarkozy said he had not known of Saleh’s presence then in France. He was asked by the police officers: “Do you understand that we can ask ourselves questions about the position of Mr Guéant, Minister of the interior and the hierarchical superior to Mr Squarcini [Bernard Squarcini, then-head of the French intelligence services who were implicated in Saleh’s flight], given his proximity with yourself, and notably concerning the point that he did not inform you or give an account of the exfiltration of Mr Saleh at a time when this was headline news in the press?”

Sarkozy’s reply was again to suggest the affair was Guéant’s responsibility alone: “Claude Guéant had been for years a remarkable colleague, who exercised missions I gave him in an indefatigable, professional and loyal manner,” said Sarkozy. “From the moment he is named Minister of the Interior he is no longer a collaborator of mine […] He from that moment his own political existence, his own operational margin of manoeuvre as minister.”

When Sarkozy, after the two days of questioning by police, was presented last Wednesday before the three magistrates in charge of the judicial investigation, they returned to the subject of Saleh, telling him: “It appears difficult to conceive that the minister of the Interior and the head of intelligence could have organised, between the two rounds of the presidential elections in 2012, the exfiltration from French territory of Bashir Saleh, a former chief of staff to Gaddafi, without you having known about it, at the very moment when you proclaimed in the media that he would be arrested if he was discovered in France […] We remind you that he is supposed to have left with the help of the authorities, while you were head of state.”

To which the former president replied: “Which authorities. Not mine. To my knowledge, Mr Djouhri was not a part of the authorities. And has someone said that I demanded or authorised this exfiltration? Of course not.”

In September last year, Bashir Saleh gave an interview in South Africa to two journalists from French daily Le Monde, when he told them: “Gaddafi said he had financed Sarkozy. Sarkozy has said that he wasn’t financed. I believe Gaddafi more than Sarkozy.” During questioning by police last week, Sarkozy was asked his opinion of the comments, to which he sarcastically replied that they were “manipulated by the newspaper Le Monde, of which the support that they have always wanted to give to me is known”.

Last month Saleh was shot and wounded in northern Johannesburg in what South African police described as an attempted robbery. Sarkozy was last week asked about the shooting, the questioning officers notifying him that according to press reports “he was readying to communicate elements susceptible to interest the present investigation”. Sarkozy declared: “I hope that no-one dares to imagine, that I would in any way be involved in an operation to settle scores.”

At his own behest, the subject moved on to the mysterious death in 2012 of Shukri Ghanem, prime minister of Libya from 2003 to 2006 and then oil minister until 2011. Ghanem was a key regime figure in charge of oil, its principal resource. He was one of the leading figures in Libya who defected from Gaddafi's regime as France and Britain launched their NATO-led intervention in the country in 2011.

Ghanem regularly took notes of events and meetings during his time in Gaddafi’s government, apparently with a view to one day publishing his memoirs. On April 29th, 2007, exactly a week after the first round of the presidential election in France, Ghanem wrote an account in Arabic in his notebook of a meeting that he had held with another prominent member of the regime, Bashir Saleh. Also present at the meeting was Gaddafi’s then-prime minister Baghdadi Ali Mahmoudi. During the meeting, wrote Ghanem in his notes, Saleh said that he had transferred 1.5 million euros to Nicolas Sarkozy.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

The fact that Ghanem wrote his notes in 2007, at a time when relations between Sarkozy and Gaddafi were at their most cordial, runs contrary to the argument put forward by the former French president and his allies that the accusations against him are levelled by former Gaddafi officials motivated by revenge for his decision to launch a military attack in 2011 that toppled the regime.

Ghanem’s notebook was found after his death: on April 29th, 2012, exactly five years after he recorded the meeting with Saleh, Ghanem's body was found floating in the River Danube in Vienna, where he had taken refuge after fleeing Libya. His death also occurred the day after Mediapart published the official document drawn up by the Gaddafi regime in December 2006 which gave its approval of funding Sarkozy’s then forthcoming campaign.

“It’s not me,” Sarkozy told police last week. “Can we stop being delirious?” He then underlined that Ghanem’s notebook was found after the French (and British) 2011 military intervention in Libya against Gaddafi. “Except that this notebook was not given to us spontaneously,” replied one of the officers questioning him. “It was seized by the Austrian authorities who had raised the subject with the Norwegians, and it was passed on to us by the Dutch. So in all likelihood these affirmations [concerning the funding of Nicolas Sarkozy’s campaign] were made before the start of the war in 2011 by an individual who, at that moment, was not against you.”

Sarkozy retorted: “I formally contest the idea according to which this notebook would have been written before the start of the hostilities. Nothing allows that to be stated.”

The questioning turned to the events surrounding the capture and death in October 2011 of Muammar Gaddafi, which occurred in circumstances which remain uncertain. Asked what he had to say about the circumstances of Gaddafi’s killing, Sarkozy, then-head of France's armed forces, replied: “Nothing. I’m not a general.”

Finally, Sarkozy was also questioned about the nature of his relations with Alexandre Djourhi, the flamboyant French businessman who played a key role in the flight from Libya, and then France, of Bashir Saleh, and who was involved as an intermediary in various dealings of Sarkozy’s team in north Africa. Djouhri, 58, born in France to Algerian parents and who is based in Switzerland, is currently held in Britain, where he was arrested in January, pending a hearing on a request by France for his extradition.

That extradition demand was lodged after he repeatedly failed to appear as summoned to testify to the current investigation into the alleged Libyan funding of Sarkozy’s 2007 election campaign, in which he is regarded as a key witness.

Enlargement : Illustration 7

The police asked Sarkozy: “What is the nature of the relations you keep with Alexandre Djourhi, who ends a number of telephone conversations he has with you by an affectionate ‘I kiss you’?” That affectionate term – in French ‘Je t’embrasse’ – is a parting address that can be used in France to notably close friends of either sex.

Sarkozy replied: “Alexandre Djouhri is a nice man, from the South, and I can tell you that within his personality, the fact of ‘kissing’ his correspondent is not an act that demonstrates an affection or singularity, it’s something he does in his own culture.”

Sarkozy said he first met Djouhri in 2006, while Claude Guéant has spoken of him as an “old acquaintance” of Sarkozy’s and Djouhri himself was recorded as saying, during a police-tapped phone conversation, that he had known Sarkozy since 1986. Asked about those differing accounts, the former French president said: “Maybe I came across him at one time or another, but I have kept no recollection.”

Sarkozy told police last week that he had no knowledge of the precise relationship between Djouhri and Claude Guéant. The investigation has already established that a payment to Guéant in March 2008 of 500,000 euros, with which he bought an apartment close to the Arc de Triomphe in central Paris, was made by Djouhri and Bashir Saleh. Guéant gave investigators an improbable explanation that the sum came from the sale of two oil paintings by 17th-century Dutch artist Andries Van Eertvelt.

During a search of Djouhri’s home in Geneva, his links to Sarkozy while president were revealed by numerous documents, including emails sent by Sarkozy to high-ranking Saudi officials and a letter signed by a senior Elysée Palace official during the latter’s presidency. The French investigation has also found several evidence that proves that Brice Hortefeux and Éric Woerth had personally intervened to help a company linked to Djouhri when it was in difficulty over tax payments.

One of Nicolas Sarkozy’s last statements during his questioning last week was, “Mediapart leads a political operation that provokes nausea”.

-------------------------

The French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse