On Thursday evening this week, the day after he had been placed under investigation by three judges for “illicit funding of an electoral campaign”, “receiving and embezzling public funds” from Libya and “passive corruption”, former French president Nicolas Sarkozy appeared in a live studio interview on the flagship news programme of French TV channel TF1 in an attempt to discredit evidence suggesting he received funds for his 2007 presidential election campaign from the regime of late Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi.

Adopting the position of a victim, he dismissed what he called “the calumny” of former members of the Tripoli regime and the Paris-based businessman who acted as an intermediary in his introduction to Gaddafi, Ziad Takiedddine, who he described as “a gang of assassins and Mafioso”, and “allegations” by Mediapart.

Notably, he waved in his hands what he called “a judicial document” that supposedly discredited the veracity of a key piece of evidence of the funding of his electoral campaign by Gaddafi which was published by Mediapart in 2012.

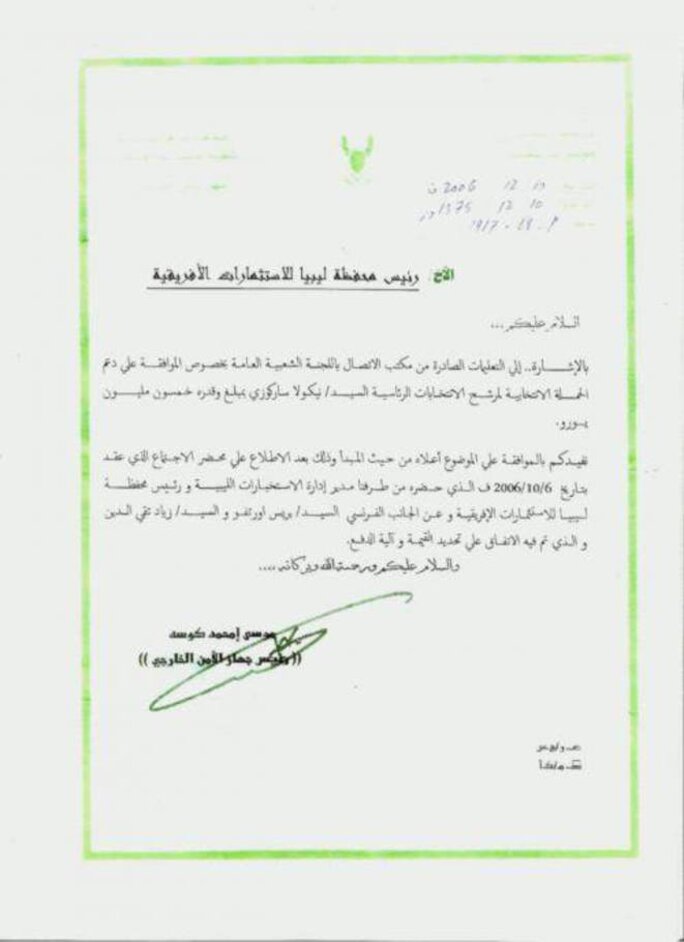

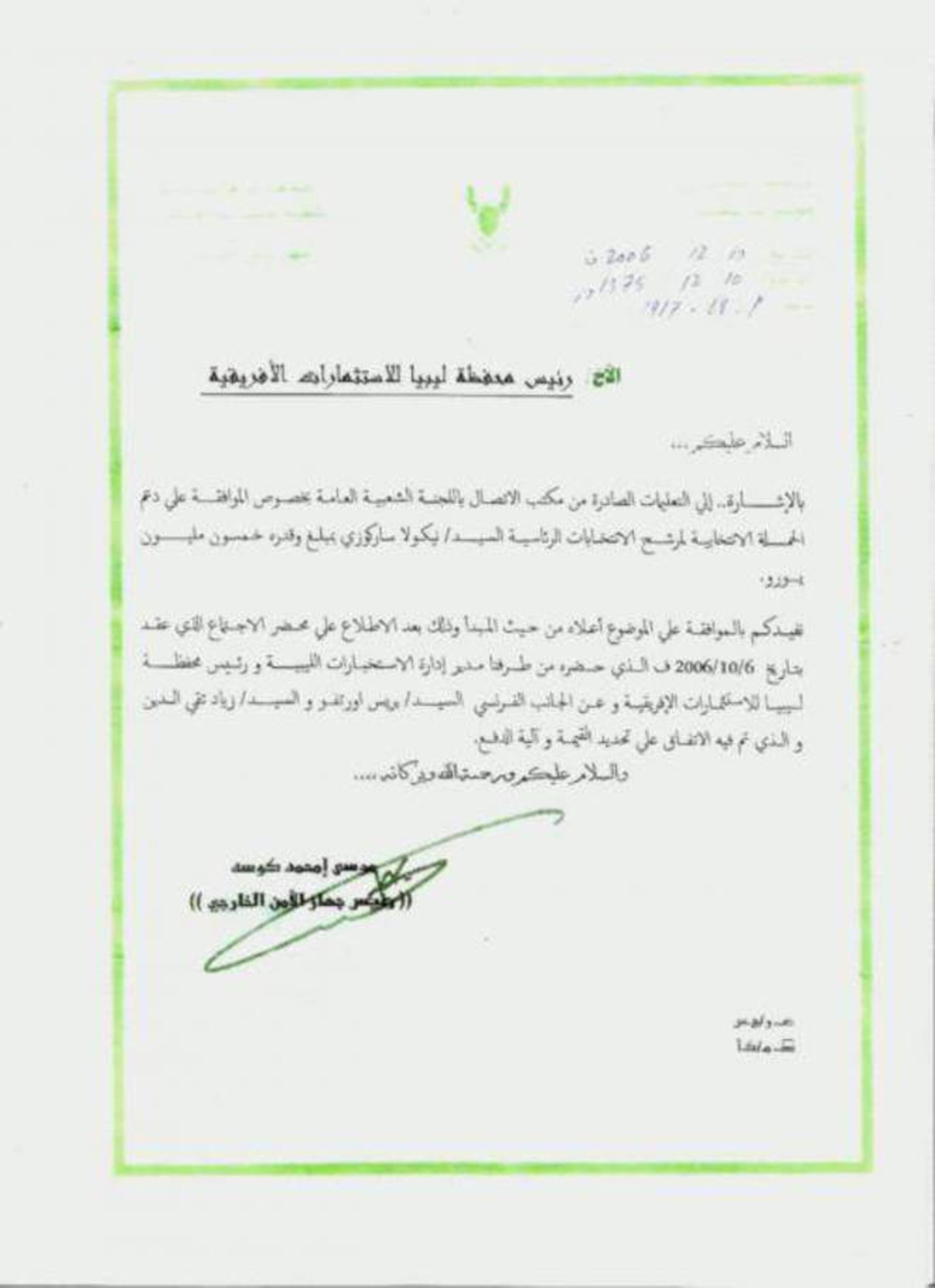

The document (see the April 28th Mediapart report here), dated December 10th 2006, was a letter announcing the approval by the then Gaddafi regime of the payment of up to 50 million euros to back Sarkozy's 2007 presidential election campaign, and was signed by Moussa Koussa, the head of the regime’s foreign intelligence service.

After the publication of the document on April 28th 2012, Sarkozy lodged a complaint against Mediapart for ‘forgery and use of forgery’, which a subsequent police investigation found no grounds to pursue further. Sarkozy then lodged a lawsuit as a civil party against Mediapart, again for ‘forgery and use of forgery’ which, under French law, automatically triggered a judicial investigation to establish the authenticity of the document.

During his interview on TF1 on Thursday evening, Sarkozy cited a 2015 report by gendarmes appointed to carry out initial verifications of the document as requested by the examining magistrate in charge of investigating its authenticity. “I quote to you two phrases,” Sarkozy told the journalist interviewing him, Gilles Bouleau, reading the conclusions of the report. “‘There therefore exists a strong probability that the document produced by Mediapart is a forgery, making it deontologically unfit for publication’.”

He then denied that his legal action against Mediapart had been thrown out by the magistrates investigating his claim. “You sued Mediapart and the case was dismissed twice,” said the interviewer. “That’s not true,” answered Sarkozy, in what was a blatant lie before an audience of more than seven million: the lawsuit launched by Sarkozy was first dismissed in a ruling dated May 30th 2016 (the full text is available here) and again after he appealed the decision in a ruling dated November 20th 2017 (see the full text here).

“The justice system, the French experts, said it was not a forgery,” countered interviewer Gilles Bouleau, to which Sarkozy replied: “No. No, no, no. They [Mediapart] succeeded in having the case against them dismissed because they said they were not aware of the false nature of the document.” Again, this was a lie (see the article by Mediapart publishing editor Edwy Plenel detailing the first ruling here). Sarkozy then read out for a second time the citation from the 2015 preliminary report, adding, “everyone knows it’s a forgery”.

The magistrates in charge of investigating the forgery claim concluded the opposite: “The totality of the investigations,” they wrote in their May 30th 2016 ruling dismissing Sarkozy’s claim, “aimed at determining whether the document published by Mediapart was materially false, meaning that aside its contents [it was] an object created by assemblage or any other means, did not allow to determine this.”

Enlargement : Illustration 1

In 2015 the magistrates ordered an expert appraisal of the document’s authenticity from IT engineer Roger Cozien, who had developed, initially for the French Ministry of Defence, a software tool that could detect the alteration of digital images and their falsification. Called Tungstene, it has subsequently been employed by a number of institutions, and also the French justice system. In the report of his analysis of the document, he informed the magistrates: “After multiple calculations and the use of all relevant filters from the Tungstene software, no trace of alteration, and even less of voluntary falsification, were detected,” reads his report. “We pushed the mathematics we have to the limit of their possibilities. Everything leads one to conclude that the digital image contained in the source file (the subject of our expert analysis) was initially the result of a digitizing process of a physical document, probably of paper matter.”

Cozien continued: “We have been able to determine that the document, which was apparently digitized, presents classic and symptomatic physical characteristics of such a physical object, presenting a certain degree of wornness, even ageing. We were able to determine that different inks were probably used, at different times during the life of the physical document. The total of these results argues very strongly in favour of a physical document that had really existed and which would have been digitized in order to produce a primary digital image.”

The report concluded: “The very great coherence between the examination and the visual and semiotic intuition on the one hand, and the results of the multi-spectral analysis on the other, leads us to favour the option of an authentic document that existed on a physical support.”

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Before Cozien's report, three court-appointed graphologists were assigned by the magistrates in charge of the case to determine the authenticity of Moussa Koussa’s signature on the document. To do this, they compare it with all available signatures of Koussa. This included his signature of approval on each of the 13 pages of the transcription of his testimony given shortly before to the French magistrates who questioned him in Qatar, where he now lives in exile.

In their conclusions, the expert graphologists noted: “The concordances observed both at a general level and in the detail allow for it to be said that the signatures ‘Q1’ [editor’s note: their reference to the document published by Mediapart] and ‘MK’ [their reference to the transcripts of Koussa’s testimony] are by the same hand.”

Their comparisons with the other available documents containing Moussa Koussa’s signature, which included two applications he made for a residency permit in France, were also positive. “The signature is made in two sequences,” they noted of all the signatures, including the document published by Mediapart. “Sloped in comparison with the base line, it crosses the mention in typescript. The graphic gesture is spontaneous and sweeping, with an ample ease in its realisation. The rhythm of its execution is rapid. The dimension of the whole is large. Neither hesitation nor trembling is observed.”

The graphologists also called on the services of a translator of Arabic, a recognised expert on different aspects of the language who, they reported, “validated elements concerning writing in the Arabic alphabet” and found that the different signatures, including that on the document, “respect the movement of Arabic writing which moves from the right to the left”. The group of experts unanimously concluded that the signature on the letter reproduced by Mediapart recording the Gaddafi regime’s approval of the payment of up to 50 million euros for Nicolas Sarkozy’s 2007 election campaign was “by the hand of Moussa Koussa”.

The investigation also received the appraisal of Patrick Haimzadeh, a former French military officer who served as a councillor for military affairs at the French embassy in Tripoli between 2001 and 2004. He is the author of a recognised book of reference about the Gaddafi regime, published in France under the title Au cœur de la Libye de Kadhafi (At the Heart of Gaddafi’s Libya’). He was questioned on the authenticity of the document. “The green colour is that of the Libyan Jamahiriya as is also the logo and the typography used in the body of the text,” he said in his report. “It is the ‘kufic’ [editor’s note: a calligraphic form of Arab script] both concerning the addressee and the title of the signatory. The document is, all the same, of poor quality and it is difficult to read and to decipher the writing in green.”

“The first date is that of the Gregorian calendar with the symbol ‘f’ corresponding to the sign used in Libya since 2000 to designate the Christian calendar,” he continued. “The second corresponds to the Libyan calendar used since 2000, a solar calendar that contains the same number of days as the Gregorian calendar. The numbers of the months and days are therefore the same, the only change being the number of the year because this calendar begins from the death of the prophet Muhammad, which is why the two letters follow the date 1374, which are abbreviations for ‘after the death of the prophet’.”

“It will be noted that since the coming to power of Gaddafi in 1969, Libya changed the calendar four times and it would appear difficult for a non-Libyan to have invented this date a posteriori. I confirm that the dates are coherent in both their correspondence and the evocation of the two calendars.”

“All documents of this sort have only these two dates. Libyan documents for internal affairs were systematically presented with these two dates, the documents addressed to foreign entities in general only the date of the Gregorian calendar. Then comes the register number which appears to me to be coherent.”

Other testimony on the document’s authenticity was provided by a former first secretary of France’s embassy in Tripoli, Éric P. (last name withheld), responsible for outside security issues. “The document presents the same appearances characteristic of official Libyan documents, both in its substance and form,” he concluded. “Unfortunately, my reading of it is limited by its bas quality and the absence of a heading. I cannot make a pronouncement on the signature of Moussa Koussa, not knowing him. However, my attention is drawn to the mentions that are made at the right-hand bottom of the document, and the presence of two annotations […] These two annotations could be notes for filing and archiving. In response to your question, I am not astonished, without speaking of the contents or the context, that such a document can exist. It is part of traditional practice of reports on decisions, each official meeting at whatever level was systematically covered in writing and a rapporteur.”

Several former Libyan officials also supported the authenticity of the document. One was Gaddafi’s former interpreter, Moftah Missouri, who, in an interview in 2013 with French public television channel France 2’s flagship current affairs programme Complément d’enquête, said the signature on the December 2006 letter was genuine. “That is the outline document, if I dare say so, for the financial support of the presidential [election] campaign of President Sarkozy,” he told the programme, speaking in French. Missouri reiterated his opinion when interviewed this week by French public radio world service Radio France Internationale broadcast on Friday, when he said he had seen the document “on the desk of the Guide [Gaddafi] at the beginning of 2007”, adding: “There is no doubt about the authenticity of the document. I know the way of writing, I know the format, I know the official paperwork, I know the person who typed it.”

But Nicolas Sarkozy’s lies during his television interview on Thursday evening were not limited to the document published by Mediapart. Complaining of the conditions of his two days of questioning by anti-corruption police on Tuesday and Wednesday, he said he was informed that he would be placed in custody for questioning only the day before. Mediapart has been informed that in fact he was notified on February 7th that he would be summoned for questioning, and was even asked to choose a date that would be most at his convenience between March 14th and 20th.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse