New witnesses have come forward who shed fresh light on the death of botany student Rémi Fraisse who died when he was struck by an offensive grenade thrown by a gendarme during a protest in south-west France in October 2014. The new statements show that Rémi, 21, who was at a protest against the building of a dam at Sivens, had his hands in the air and was shouting “stop” to gendarmes when he was hit and killed by the grenade. They also challenge some details in the gendarmes' version of events at the violent confrontations at the site.

The examining magistrates investigating the student's death, Anissa Oumohand and Élodie Billot, received these new statements thanks to an appeal launched by Rémi Fraisse's parents and the tenacity of their lawyers Claire Dujardin, Arié Alimi and Étienne Noël. The majority of these witnesses had not been questioned by gendarmes from the detective unit at Toulouse in south-west France who are in charge of the day-to-day investigation – they were not very keen on being so anyway – but they agreed to speak to the independent judges.

The new statements that Mediapart has had access to are very important in illuminating the exact circumstances of the death of Rémi Fraisse on the night of 25th to 26th October, 2014 at the protest site at Sivens. Each one of the new witnesses was present in the area where the clashes took place at the time when Rémi Fraisse was killed. Some say they saw everything, others admit they did not, but each one was able to mark their position that night on a sketch handed to the judges.

One of the witnesses, Marc, who was questioned on February 9th, explained that after he was hit by a Flash-Ball – a non-lethal riot control projectile – he was helped by a young man who must have been Rémi Fraisse, just before the young man was killed. Having gone to see the clashes “out of curiosity” and “as an observer”, the 57-year-old environmental activist says he heard warnings from gendarmes, then saw a group of them on foot making their way out of the site's “living area”. He said he was hit“in the throat” by a Flash-Ball as he was about to leave.

This so-called living area where the gendarmes were dug in was, in fact, a base built by the construction firm at the site to house its heavy plant machinery, equipment and changing rooms. It was protected by two 2-metre high fences and a ditch 2.5 metres deep, and consisted simply of a prefabricated hut and a generator, which had been set on fire the night before when the security guards had come under attack and had to be replaced by riot police. The next day it was the gendarmes who protected the site.

“I fell into the arms of the young man whom I was with,” said Marc. “Later, a haze of tear gas fell. The young man took me a bit further away and I no longer saw the gendarme [editor's note, the one who had fired the Flash-Ball]. It was 1.20 a.m., I'm sure of that because I asked the time,” he said. “He took me close to the fire and then he went off again. He felt angry over what had just happened, as I did too, incidentally,” he added. This scene thus took place just minutes before Rémi Fraisse was mortally wounded by a grenade at around 1.45 a.m. Marc learnt about the young man's death the following day and thought he recognised Rémi Fraisse from his photo. Another witness later confirmed it to him.

A short while after this episode near the fire several witnesses saw Rémi Fraisse with arms raised near the living area fence, and some heard him say “Stop!” to the gendarmes. One of these witnesses was 19-year-old Zacharie, who was also questioned by the examining magistrates on February 9th. He said he was traumatised by the scenes of violence he saw that night.

“I saw someone dressed in black who passed by me, perhaps with a bag. I saw a bag which was slightly oval in shape, he has his arms raised as he said “Stop! Stop!”. I didn't understand how this person could do that in that atmosphere of violence. What I saw there were several explosions in one go. I want to point out that in the meantime I lost sight of the person dressed in black for two, three minutes,” continued Zacharie. “I looked again in the direction of the CRS [editor's note, a reference to riot police though in fact they were gendarmes] and I saw a heap on the ground. One could see that he had something on his head, dreadlocks. One of my mates tried to pull this person but was hit in the back by a Flash-Ball. The gendarmes or CRS went towards him and dragged him.” Zacharie, too, only realised the full significance of what he had seen the next day, when he learnt about Remi Fraisse's death.

Another witness, Christian, 38, who was questioned on February 11th, told a different story but claimed to be very sure about it. He said that he saw several gendarmes outside the living area. “When they started their assault the seven or eight gendarmes were behind a stump that must have been a metre high; they hid there, they deliberately aimed at Rémi. They weren't even ten metres from Rémi Fraisse. I saw them take aim and fire. They took aim with what could have been a Flash-Ball or a grenade launcher. There were gendarmes with shields protecting them. I saw them fire with Flash-Balls. They did that several times. They really wanted to catch someone that day, I mean arrest. And the way in which they came to seek out Rémi afterwards, that was to arrest him,” said Christian.

This witness, who says he received a Flash-Ball on the thigh during the disturbances, did not know Rémi Fraisse. “That evening I said: they're taking a colleague, but I didn't know who it was. He was there with his arms raised, he was shouting: 'Stop firing!'”

Two floodlights lit up the area

Alejandra, 27, another witness, was questioned on February 11th. “Five metres from us there was a group of people on the hill throwing stones and the police started to respond to these shots (sic). It must have been midnight. The police were firing Flash-Balls, tear gas and stun grenades. The police were telling us to clear off but we didn't want to move. I got a stun grenade on my body, it rolled on the ground and exploded less than a metre from me. I still have the scar on my leg. We were ten, fifteen metres away. When I was fired on I was afraid and I went back to the clay mound. I was then between 30 and 50 metres from the fence. That must have been around one o'clock in the morning,” said Alejandra.

“Afterwards, I saw several people who were a little too close to the wire fence, two or three metres away, there was a girl who was dancing near the wire fence, and there was a person who was raising their hands, just at the edge of the ditch. I can't say if it was a boy or a girl. At that moment the police had withdrawn but there was a group of cops to the left of the wire fence, and some gendarmes were opening the gate, coming out of the [living] area and chucking tear gas and stun grenades at us. There were between six and eight of them,” Alejandra continued.

“After they'd fired they returned behind the wire fence. They did that several times. The gendarmes who were on the other side came out sometimes and threw grenades at us, perhaps stun or tear gas, I can't be sure. At the beginning they fired a long way away, but with the wind the gas dispersed and didn't reach the demonstrators, and as they really wanted to disperse us they started to fire closer to us. First of all I ran off, and when I turned around I saw the gendarmes firing tear gas next to the wire fence and retrieving a friend.” At the time Alejandra did not know that it was very probably Rémi Fraisse. “I am not sure that it was the same person,” she said candidly. “But what I can say is that after the gendarmes retrieved the person I no longer saw the person with raised arms.”

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Several witnesses have stated that from time to time the gendarmes lit up the site where the clashes were taking place with the help of two large floodlights. However, in their statements the gendarmes say that they used night vision binoculars. Some witnesses also declared that the force used that night by the gendarmes was disproportionate, and that they had made several sorties out of the fenced living area to fire at protesters and/or carry out arrests.

David, 20, who was questioned by the judges on February 11th, said he had seen the gendarmes make those sorties and light up the area with floodlights. “In the glow of the lights I saw a body being dragged by people in helmets,” he said. “At the time I wondered if it was a demonstrator or a gendarme or someone being arrested. I just saw silhouettes passing in front of the lights. At the time I was on the hill.”

Another person present, Arthur, 24, who had already been questioned by gendarmes, was questioned by the judges on February 9th and also described the use of the floodlights, and spoke about the sorties that the gendarmes made from the living area.

“I saw two of them, sure, one to the right, one to the left,” he said of the floodlights. “One was up at least ten metres high, another less high was on a van. The high one was the most powerful, I presume it was on a pylon. I know that on that night there were some problems with the latter [light], or it was done deliberately, I don't know. There were times, one had the impression that they were firing tear gas when the spotlight was out, and immediately you couldn't see anything any more, including when they turned it back on again, because it made a screen with the smoke. The other floodlight, it didn't seem to have been turned off. But I remember that sometimes it was complete black, with just the light of the projectiles.”

“On some occasions they came out, they went 25 metres in the direction of the demonstrators, they hurled stuff to make them go back, tear gas,” said Arthur. “They did that at least ten times. There must have been around fifteen of them each time they came out.” The young man said he did not see Rémi Fraisse fall. “I wasn't looking in that direction and I didn't hear shouting ...it was confused. I think that it was at a time when the lights were out, the big floodlight at least. The place where Rémi Fraisse was.” This was, according to Arthur, only about ten metres from the wire fence. “It was lit by the small floodlight. The big floodlight was going on and off. At the time that it was off we heard several grenades explode, and at the time it was switched on again we saw them come out to fetch Rémi. I was 30 metres from Rémi Fraisse, diagonally to the left,” said Arthur.

More than 700 grenades thrown

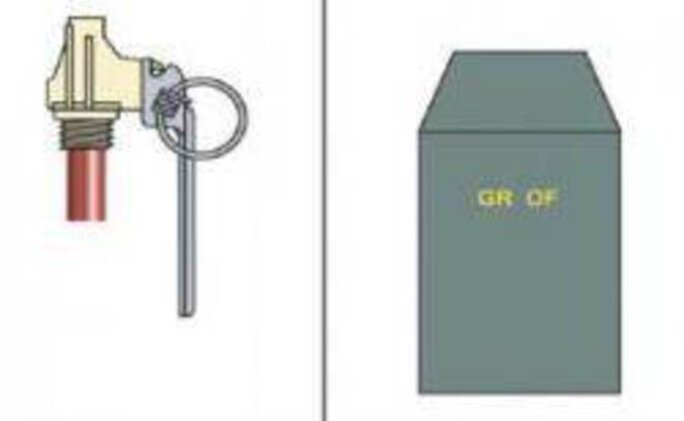

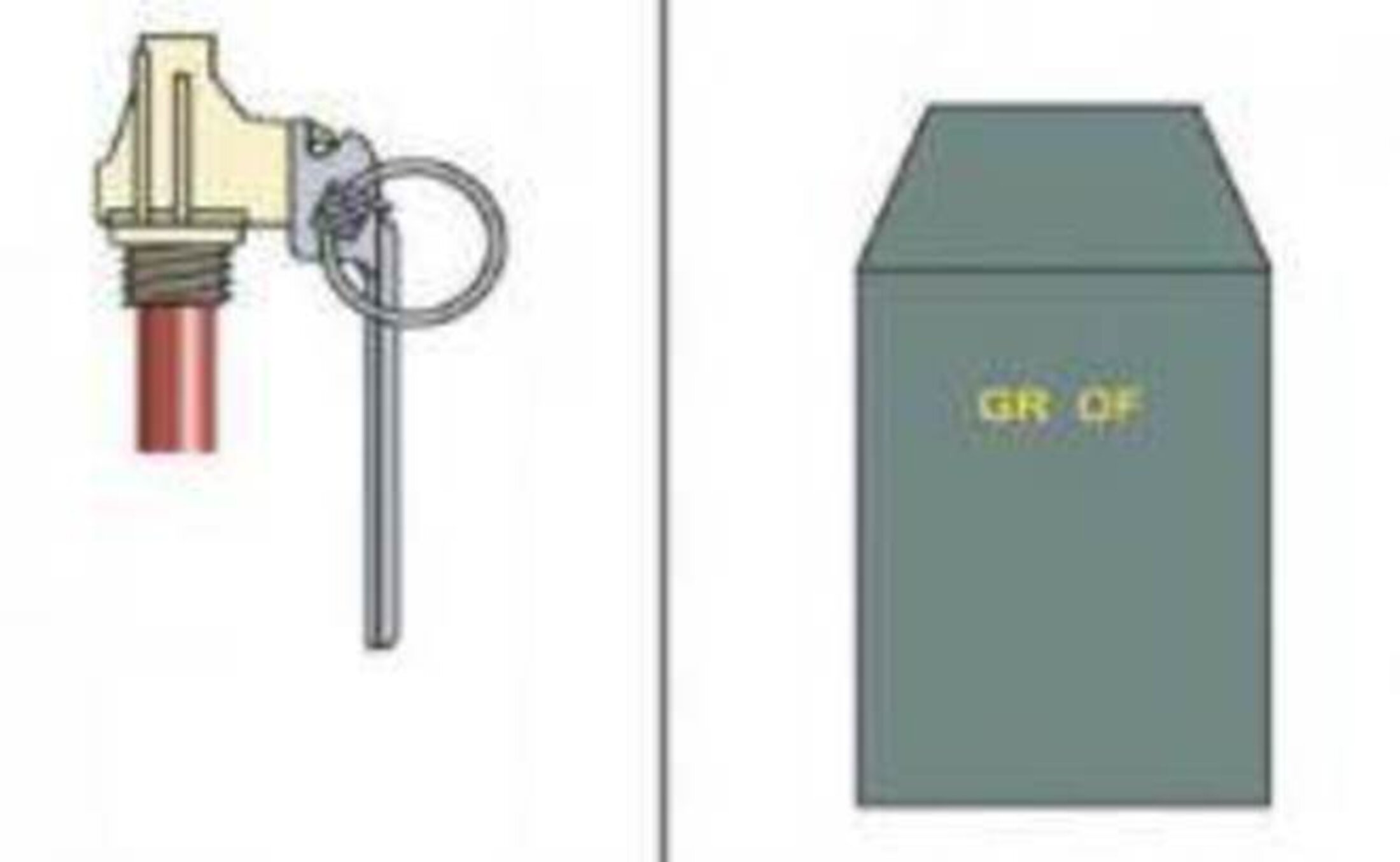

According to the official count, the number of munitions fired that night was impressive: more than 700 grenade of all types. This included 312 P7 tear gas grenades, 261 CM6 tear gas grenades, 78 F4 stun grenades, 10 GLI tear gas grenades, 42 OF offensive grenades, plus 74 40mm rubber LBD rounds. The most dangerous grenades, the OF offensive grenades, were thrown by hand at a maximum distance of ten to 15 metres. Their use was banned after Rémi Fraisse's death.

According to the statements made by the gendarmes, who highlighted the violence of the demonstrators, it was a “lobbed” offensive grenade, thrown by hand over the fence from inside the living area, that accidentally hit Rémi Fraisse.

What is still not clear is just why the gendarmes were given the order to hold the living area that night. A meeting had been organised at the local prefecture on October 21st, 2014, to prepare for a planned festive gathering at the Sivens protest site on October 25th, at which several thousand protesters were expected. The minutes of the meeting, seen by Mediapart, show that a great deal of time was taken up with the issue of traffic circulation and parking. But an assessment of the risks involved in the protest also took place.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

“During that meeting our organisations asked that there should be no more heavy plant machinery on the site to avoid things getting out of hand,” said Ben Lefetey, a spokesperson for the anti-dam group the Collectif du Testet, who was questioned as a witness. “The prefecture had confirmed that the machines would be withdrawn from the site. Concerning the forces of law and order, on the same basis the prefecture made a commitment that there would be no law and order forces near the demonstration,” Lefetey said.

Yet though the machines were removed, the prefabricated hut and the generator remained, watched over by security guards. Given that the hut and generator were still there, and given that there had already been weeks of tension between environmental activists on the one hand and local farmers and the forces of law and order on the other, it was quite foreseeable from that point on that there was a risk incidents could become more serious. According to several activists, these predictable incidents could only result in “discrediting the movement”. They pointed out that the local state intelligence agency, the Service Départemental du Renseignement Territorial (SDRT), had already predicted that small violent groups would arrive at the site.

“I was very surprised that clashes of such a scale took place on the site, leading to this tragedy,” said Ben Lefetey. “I still haven't understood why the state decided to maintain the forces of law and order on the site when from Saturday morning there was just a fence to protect. So for me the state exposed the forces of law and order and the people they were confronting to risk. This policy decision seems disproportionate to me in relation to the stakes at the site. Especially as I knew that the report [editor's note, on the dam project] that was going to be made public on October 27th was going to call into question the dam project and thus probably lead to a suspension of the works.”

The government was itself watching events at Sivens closely. The intervention report from the lieutenant-colonel who led the gendarme tactical contingent at Sivens notes that, at around 5.30 p.m. and the start of the first incidents on Saturday October 25th, there was a telephone conversation between the GGD 81 (the gendarme group on site, who came from the local département or county of the Tarn) and the head of the gendarmerie, the Directeur Général de la Gendarmerie Nationale (DGGN), Denis Favier, in which the order was given to “proceed to arrests”. This is proof that the situation was interesting the authorities at the highest levels.

The lieutenant-colonel who commanded the unit on that evening had received the order to “hold position”. When questioned as a witness the officer said: “I want to make clear that the prefect for the Tarn [département], through the group commander, had asked us to show extreme firmness concerning protesters in relation to all forms of violence towards the forces of order.”

'I saw a heap on the ground'

However, the interior minister Bernard Cazeneuve gave a diametrically opposed version when he spoke at the National Assembly on November 12th, 2014. “Were there any instructions on my part that there should be firmness in a context where there was tension? I gave the opposite instructions, and I say that again before the elected assembly,” declared the minister.

“For weeks I was aware of the climate of extreme tension at Sivens. I wanted to make sure that this did not lead to a tragedy,” insisted Cazeneuve. “That is, moreover, why there were no forces already in place on the Friday evening at Sivens, and if there were later it is because on the night of Friday to Saturday there were clashes that bore witness to the violence of a small group who had nothing to do with the peaceful protesters at Sivens,” he said.

What precise orders had the prefect – the state's local representative responsible for public safety – received from the Ministry of the Interior? What instructions had the prefect then passed on to his chief of staff? An attempt by the Fraisse family's lawyers to get the Tarn prefect, Thierry Gentilhomme, questioned and his conversations with the gendarmes and the government – the interior ministry, the prime minister's office and even the president's office – examined were rejected by the judges and then by the court of appeal in Toulouse.

The gendarme who threw the fatal grenade, Sergeant J., was interviewed at 4 a.m. on Sunday 26th October, just over two hours after the tragedy. “It was the first time, in my career as a mobile gendarme [editor's note, the Gendarmerie Mobile is a special unit used in part for riot control], that I saw demonstrators so determined, violent and aggressive, in their words as well as their acts,” he told investigators.

Later he described the moments leading up to the throwing of the fatal grenade. “They were throwing stones at us. At that point my squadron commander made a request for reinforcements. In view of the situation which was, to my eyes, critical I took the decision to throw an offensive grenade. Before throwing it I warned the demonstrators of my intention. There was a fence in front of me and I had to throw [the grenade] over it. ….I took care to avoid hurling it on the demonstrators themselves, but instead close to them.”

Enlargement : Illustration 4

The sergeant said that at the time the grenade left his hand the demonstrators were “facing me”. He added: “I threw it to my right to avoid them, but there again, as I've told you, they were moving a lot and I didn't know what they were doing at the moment that I actually threw the grenade.” Sergeant J. said the grenade exploded near the people who were there though he says he did not himself see what happened after throwing his grenade. “However, two of my colleagues told me they saw someone fall following the explosion. First of all I took the [night-vision goggles] and I looked to see if the demonstrators had left. They had left. But on the other hand I saw a heap on the ground. I asked my colleague who was beside me to light up the place where this heap was. At that point we made out that it was a person who was on the ground.”

On 18 March the investigating judges placed Sergeant J. under the status of “assisted witness” in relation to the investigation into “unintentional homicide”. This status lies between that of an ordinary witness and a person who is being formally investigated in relation to the allegations. Under French law it refers to where there is “evidence making it probable that [the person concerned] could have taken part in the committing of offences which have been referred to the judge”. The gendarme's lawyer, Jean Tamalet, now considers that his client no longer faces the likelihood of being charged over events at Sivens.

Meanwhile the Fraisse family's lawyers hope that the two judges in charge of the investigation are now going to investigate higher up the chain of responsibility that led to certain decisions being made and which ultimately ended in the clashes and the death of Rémi Fraisse.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter