It was Friday the 13th, October 2017. Four months earlier Bruno Lafont, 61, had left as co-chairman and director of the world cement giant LafargeHolcim which has an annual turnover of 30 billion euros and which was formed by the 2015 merger of the French firm Lafarge and its Swiss counterpart Holcim.

Lafont is a leading figure in the world of French capitalism and also a wealthy man. When he left the group in which he has spent all his professional life after graduating from France's elite École Nationale d'Administration (ENA) in 1982, Lafont pocketed a golden parachute payment of six million euros. That was on top of the salary that he had been earning which was as high as 2 or even 4 million euros a year at times. He owns a 550 m2 flat in Paris's XVI arrondissement, acres of woods and forest in the Somme département (or county) in northern France and shares in several companies.

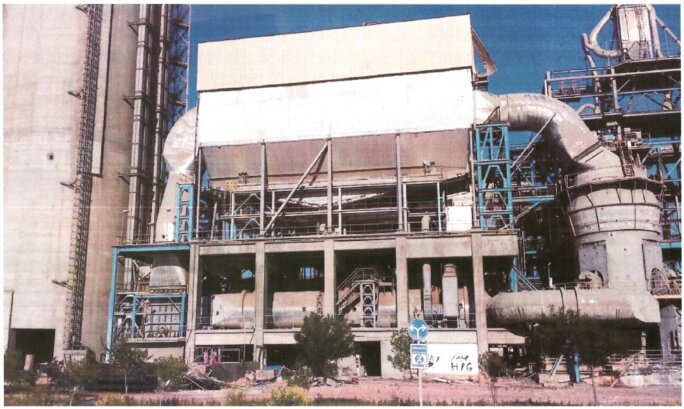

Enlargement : Illustration 1

But Bruno Lafont is also a worried man. He knows that the company which he headed is in choppy legal waters. For several months judges have been investigating suspicions that between 2011 and 2015 Lafarge, as it then still was, had been paying armed terrorist groups in Syria. Its sole aim: to ensure that its new cement factory 90 kilometres from Islamic State's headquarters in Raqqa was kept in production. At that time Lafont was Lafarge's chief executive officer.

On this particular Friday the 13th last year, Bruno Lafont telephoned the new boss of the public relations agency Publicis Consultants, Clément Léonarduzzi, whose role is to protect his client's image. Léonarduzzi himself had just put the phone down on a conversation with Anne Méaux, the high priestess of PR among France's leading companies, and who was herself defending Lafarge's corporate interests. “Her line, for the moment, is that everyone is watching their step. In particular there must be no fronts opening up because the Swiss are going to get angry,” Léonarduzzi told his client Bruno Lafont.

Neither of the men seemed to suspect that they were being eavesdropped by a French customs investigator. The phone-tap had been requested by the examining magistrates in the case, judges Charlotte Bilger, David de Pas and Renaud Van Ruymbeke.

On the phone Lafarge's former CEO is heard to say: “What I don't know, if you like, is what LH [editor's note, LafargeHolcim] can do against me.” What follows, in a transcript of the call that Mediapart has seen, is a rare and important insight into the panic that can take hold of a company faced with such serious claims: that a multinational financed terrorism for reasons of profit. For the cement works that the company wanted to keep producing at any price, even to the extent of doing a secret deal with Islamic State in the middle of the war in Syria, had been built at the cost of nearly 700 million dollars.

Clément Léonarduzzi told his client Brunto Lamont how the company could target him. He said: “Straight off, I can imagine two things: the first, is to try to put the blame on you. And the second is to try to discredit you in relation to those you are speaking to, to explain that you completely messed up in this case and that you must not be given other responsibilities and then that's all. So it's one word against another, one point of view against another. That doesn't scare me a whole lot.”

Some of the phrases that then follow come across as threats: “collective blame”, “weapon of mass destruction” and so on.

Bruno Lafont: “For me, my question is, taking account of what you've heard, what is it that frightens them so much about me speaking?”

Clément Léonarduzzi: “If you talk, you're going to open a box and many things are going to come out of the box. It's that that frightens them. In other words, tomorrow, a boss of your level, of your reputation, of your stature, who in public [says] 'There you go, that's what happened, that's how it happens, here's why we did this, here's why we did that', that's going to open an unhealthy media front … If you come out tomorrow they're going to get hammered in all directions, that's for sure. I think it's that that frightens them. Second thing: just how far are you going to go in the collective blame?”

Bruno Lamont: “No, but for sure, there are some who hope I don't say that there wasn't good governance.”

Clément Léonarduzzi: “It's a weapon of mass destruction. Then all the people behind, as Méaux says, there's [Nassef] Sawiris [editor's note, a director at LafargeHolcim], there's [Paul] Desmarais [Jr] [another director], all these people behind are in anguish.”

Bruno Lafont: Yes, yes I understand very well.”

Clément Léonarduzzi: “Yes, but we have to turn it round. In other words, we must make it an instrument of power for us.”

Bruno Lafont: “Well yes, that's it exactly. I think their quite virulent attack against us, me, shows there is concern.”

'There's no question of compromising my dignity'

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The “concern” that Bruno Lafont – who did not respond to Mediapart's request for an interview – was talking about can be summed up succinctly. Just how far will the Lafarge affair go or, to put it in the context of the judicial investigation, just who will it affect? Up to now six former executives from the cement firm have been placed under investigation – one step short of charges being brought – for “financing terrorism”. Some have even acknowledged the facts of the case, which have been widely documented.

As Mediapart has reported, the judges are looking at a total of 15 million dollars of suspect payments to middlemen. The investigation has already identified at least eight million euros of taxes and commissions destined for Islamic State and other terrorist organisations.

Among those implicated is Bruno Lafont himself, who was placed under formal investigation on December 8th, 2017, though he escaped being remanded in custody as the judges had asked. In a statement issued on April 3rd, 2018, Lafont said he “strongly disputes the accusations levelled against me”.

But there are other implications that go beyond even the company's executives. For above a company's management is that company's shareholders. So in order to get a clearer view in the scale of responsibility inside Lafarge, the French judicial authorities recently teamed up with their Belgian counterparts to carry out a joint investigation. This is because it is a Belgian group, Groupe Bruxelles Lambert (GBL) who were Lafarge's leading shareholders at the time of these events.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

It was in the context of this judicial partnership that a phone-tap was carried out in Belgium on November 17th, 2017, which recorded an embarrassing conversation between Gérald Frère, chairman of the board at GBL, and one of the group's directors, Victor Delloye. Speaking about Lafrage's shareholders Delloye said, as Le Monde has revealed: “What they could be criticised for is to have remained passive. To not have been curious. That it served them well, and that's a crime. Because funding terrorism, that's serious. Certain things are not said at the board … the board played the innocent.”

The questioning of some Lafarge executives as part of the investigation has meanwhile tended to suggest that erratic governance at the multinational could indeed have allowed the unthinkable to occur. This can be seen in the alarm shown by the former director of security at the group, Jean-Claude Veillard, who has been placed under investigation, when he was questioned on April 3rd, 2018. “I can't explain the decision to maintain production [at the factory],” he said. “As I've told you, from the end of 2011 I was campaigning for the abandoning of production and the evacuation of the personnel. I expressed this point of view on several occasions. I have no decision-making power in relation to the maintenance or the continuation of production.”

The man who was director of the factory concerned from 2014, Frédéric Jolibois, who has also been placed under investigation, told the judges on March 29th: “Since being placed under investigation I've been able to find out about the case, which has plunged me into a state of shock and consternation. I learnt that the operations in Syria as well as the problems linked to the security of the employees were known by my superiors and that they were not communicated to me in full before I took up my position.”

His predecessor Bruno Pescheux was even more accusatory when he was questioned by the judges on December 1st, 2017, and then February 2nd. He described in minute detail how he was summoned ahead of being sacked for serious misconduct “which, in short, came down to putting all the responsibility for what happened in Syria on me, and which exonerated the Lafarge company from all responsibility”.

He added: “I've been informed nonetheless that I can't be sacked for serious misconduct if an agreement is reached. Two weeks later I received a proposal which amounted to buying my silence. I refused. There's no question of compromising my dignity by signing such an agreement. My lawyer explained to me that Lafarge was proposing to silence me to restore my own rights.”

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter