Was France attacked mainly because of who it is or chiefly because of what it has done? Were we attacked because Islamic State finds our way of life unbearable, or mostly as a reprisal for French bombing raids carried out in Iraq since September 2014 and in Syria since September this year?

This dispute about how to interpret the November 13th attacks has fuelled social networks, café conversations and many media articles and commentaries arguing for and against. Without doubt the most emblematic article of this kind was written by a young woman called Sarah Roubato in a Mediapart blog entitled 'Letter to my generation' in English (in the original French it was called 'Lettre à ma génération: moi je n’irai pas qu’en terrasse', a reference to the campaign to continue use café terraces even though they had been targeted by the terrorists). The blog was read and shared more than a million times, and within a few hours it became by far the most-read article ever on Mediapart, and attracted responses (here and here) and counter-responses.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The best way to get away from these questions that are dividing a France still shaken and traumatised by the massacres is simply not to choose between the possible interpretations. For one thing, there is no need to quibble over the motives in order to weep for the dead. For another, both arguments feature in the various claims of responsibility made by Islamic State. The group has said that it wanted to attack the “crusader countries” who bomb “Muslims in the land of the Caliphate with their aeroplanes” just as it wanted to target the “capital of abominations and perversion” that is Paris and rejoiced at the fact that it had struck “hundreds of idolaters in a festival of perversity as well as other targets in the tenth, eleventh and eighteenth arrondissements [editor's note, districts of central Paris]”.

Any simplistic Manichean interpretation becomes futile when the scale of the situation demands what the French sociologist Edgar Morin calls the “imperative of complexity”. This idea is underlined by a strong and to-the-point article in the online magazine Ballast which states: “Those who think they can encapsulate such issues in a single response (whether it be 'hatred of freedom and civilisation', 'spiritual vacuum and materialism', 'poverty and despair', 'global capitalism', 'Zionism', 'Islam', 'the racial system' or 'state Islamophobia') do not clarify anything: they simply reveal their own obsessions.”

Already, immediately following the attacks, the historian Patrick Boucheron and the writer Matthieu Riboulet had underlined the need to “spurn any talk which claims, however surreptitiously, to find that the current situation confirms a previously-formulated conviction”.

Nonetheless, it is still useful to raise questions over the targets chosen by the attackers, as understanding the terrorists allows one not to excuse them but to combat them better. And the analysis varies considerably depending on whether one puts the emphasis on lifestyle or French foreign policy.

There is certainly a series of potential motives and factors that might have led to France being targeted and which feed upon each other. These include the number of French and French-speaking jihadists that are in Syria, the secular and open nature of French society, the country's colonial and post-colonial history, its overseas interventions and the country's geographical situation.

But simply by placing emphasis on one or other of these possible motives one is already determining in advance the political response that one adopts towards those who brought war into the heart of the capital. Moreover, given the stepping up of military strikes in Syria one senses that the dominant view is that France was attacked, above all else, because it embodies the idea of a “nation of liberty”.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

In such circumstances it is hard not to recall that during the funeral of 17 American sailors killed on the guided-missile destroyer USS Cole in October 2000 by al Qaeda, the then-US president Bill Clinton said they had died in the “cause of freedom”. He preferred to overlook the fact that the ship had been involved in a suffocating and murderous blockade of Iraq. It was in the name of this same freedom that, three years later, Clinton's successor George W. Bush decided to invade Iraq, launching the “Mother of all Battles” that helped lead to the creation of Islamic State, which emerged in that country's American prisons from 2006.

To correlate a country's military and geopolitical activity with a terrorist act carried out on its soil does not mean making a direct and absurd link between foreign military interventions and attacks. But to ignore the way in which Islamic State, in committing its atrocities on French soil, is expecting precisely those reprisals that are likely to motivate the next wave of jihadists, would also be just as misguided, as the historian Jean-Pierre Filiu explained on France Inter radio following the attacks.

This is what gives rise to concern in the face of the warlike approach now adopted by President François Hollande – see for example the article by Mediapart's editor-in-chief Edwy Plenel – which is dangerous not only because it prolongs the impasse of the endless “war on terrorism” launched by President Bush, but also because this rhetoric, which has neither the strategy nor the means to match its ambitions, might seem suicidal.

This warlike rhetoric is even more worrying if one regards the 130 killed and the 350 people injured on Friday November 13th as civilian casualties of wars, in Iraq and Syria, Mali and the Central African Republic, into which the socialist government has dragged France without a vote in Parliament – until last Wednesday's vote to continue air strikes against IS in Syria – or the backing of French society.

Of course, this sad reality does not exonerate IS from its crimes, nor does it validate the assertions of those who seek to make France jointly responsible for the mass murder that it has just suffered because of geopolitical errors. Nor does the fact that France might today be the victim of the “return of the boomerang” over its past mistakes, to use political expert Jean-François Bayart's expression, exclude the possibility that there might be many other threats, some of which have nothing to do with the country's overseas interventions nor even the French Republic itself.

So while we can reject the notion of what rightwing weekly news magazine Le Point calls “our war” (see left), we cannot either simply content ourselves with proclaiming “your wars, our deaths”, as one blogger put it. This is not simply because the pacifist movement in France barely registers and the fact that the decisions to carry out air strikes far away have failed to elicit public protests and demonstrations, unlike in 1991 and 2003 over the first and second Iraq wars.

The other reason is that those who died on November 13th were not simply killed as a reprisal for French military operations but also because of what they represented. And what they embodied was not primarily a French lifestyle based on alcohol, flirting and having fun, but above all the “grey zone” - inhabited by people who refuse to think in simplistic black and white terms - that Islamic State has said it wants to destroy.

'The extinction of the grey zone'

As historian Pierre-Jean Luizard, a specialist on the Middle East, told Mediapart in an interview just after the attacks: “The targets, football supporters and the fashionable youth of the eastern parts of Paris, were not chosen by chance. In Daesh's [editor's note, Daesh is the Arabic acronym for Islamic State and the word is often used in France] claims of responsibility one finds the usual diatribes against idolatry, towards football players in particular, and against the places of perversion which are for them concert halls. But it's also a way of attacking young people who are the most tolerant towards Islam, a population that thinks about the situation in the world, an educated public that tries to understand,” said Luizard.

“In the districts that were attacked you can see young people with a cigarette and a glass of wine in their hand, socialising alongside those who go to the area's strict mosque. That's what IS wants to break, by pushing French society back into itself, into a fear of others, by producing irrational reactions where explanations and reflections no longer have a place, to end up with what they've succeeded in achieving in the Middle East; where people no longer look at each other in terms of what they think and what they are, but in terms of which community they belong to. They want to drag French society – and this includes taking French Muslims along as hostages - into a one-way process, into community clashes from which they are the only ones to emerge victorious.”

On November 13th it was in fact neither sailors on a destroyer nor caricaturists who were killed, but crowds chosen at random; though this does not mean they were chosen without reason. In particular the targets were young people at concerts or sitting at a café or a restaurant. This doubtless partially explains how the attacks were seen as seeking to undermine a lifestyle, producing a corresponding reaction from society against that. This reaction was amplified by the power of social media, which did not exist during the bombing attacks in France of 1986 and 1995. Nor did those bombings spark the displaying of banners and flags seen after these most recent attacks.

If the suicide bombers had managed to carry out as big a massacre as they had planned at the Stade de France in Saint-Denis, an area that is poorer and has more Muslims than the eastern districts of Paris, then the focus of the reaction would have been more on the sporting terraces than the restaurant and café terraces, and more on the secondary schools of Seine-Saint-Denis – the département or county where Saint-Denis is located – than on the fashionable youth of east Paris. And the focus would then have been on how the alleged soldiers of the Islamic State caliphate had killed lots of Muslims and not just “crusaders”.

But in fact the men and women who live near to and go to the Stade de France, the Petit Cambodge restaurant, La Bonne Bière and La Belle Équipe cafés and the Bataclan concert hall all belong to Islamic State's main target group. This target group includes anyone who does not have a stark Manichean view of reality, whether they are fundamentalist Muslims, non-fundamentalist Muslims or secular people of no faith.

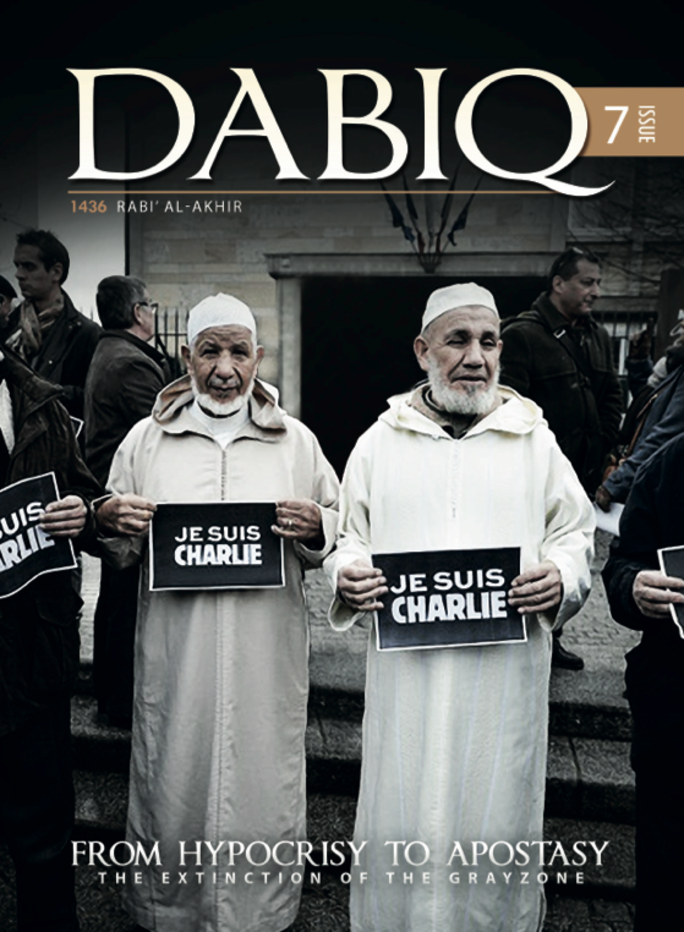

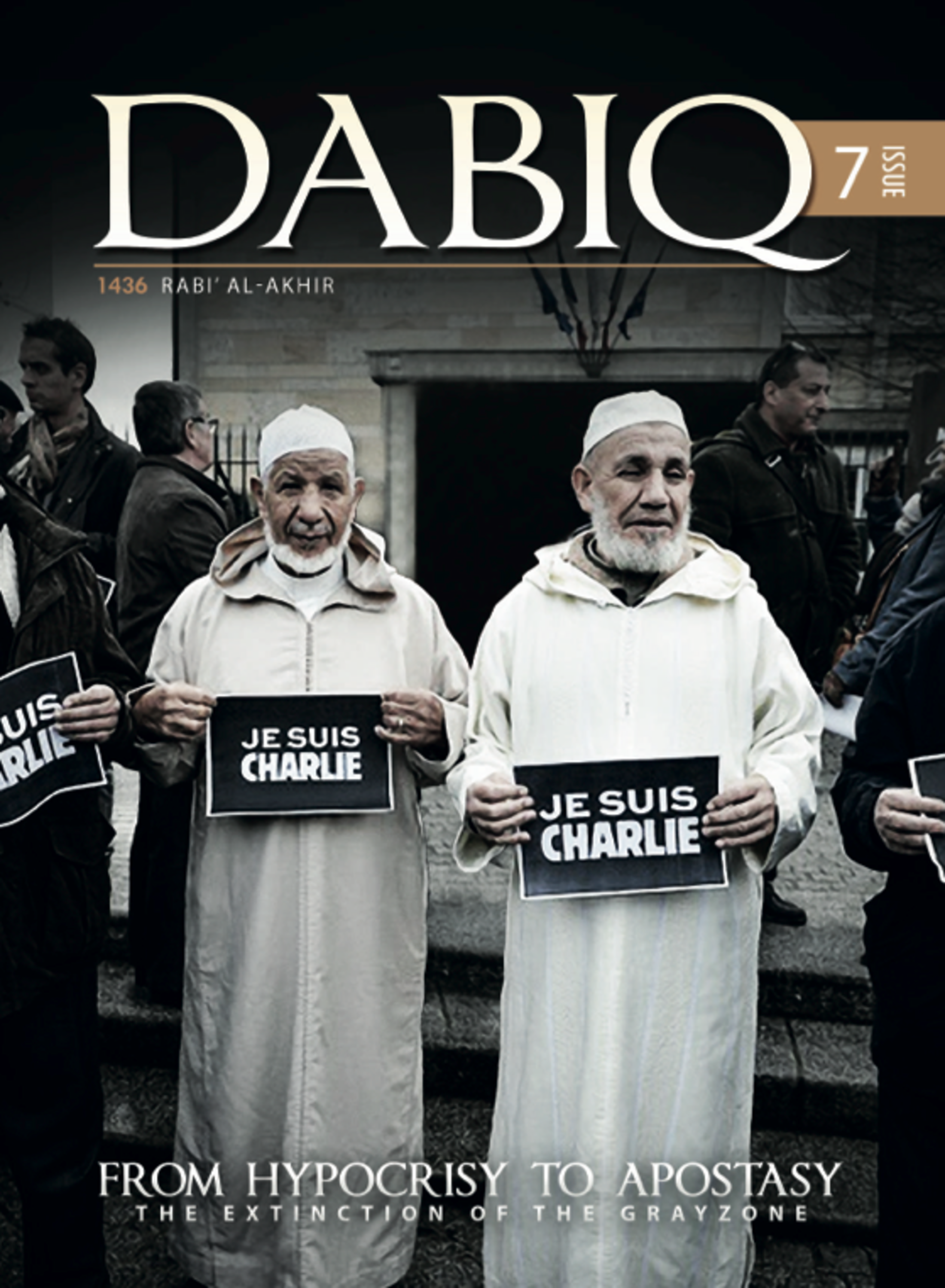

Enlargement : Illustration 4

In February 2015 Islamic State's magazine Dabiq devoted its front page and an article several pages long to the “extinction of the grey zone”, meaning people who refuse to think about the world in black and white terms. The article quoted Osama bin Laden who said “the world is today divided into two camps. [George W.] Bush told the truth when he said: 'Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists.' Either you are with the crusaders or you are with Islam.”

This Islamic State article targeted “infidels” but also, even particularly, targeted those Muslims who accept living alongside “infidels” rather than joining the caliphate. By proclaiming the objective that there should now only be “two camps, without a third way”, the IS's propaganda organ hopes to arrive at a world in which “in the end, there will be absolutely no more place for movements or appeals that blur the lines”.

By a tragic coincidence one of the victims of the Bataclan massacre was an academic who worked precisely on those social issues that do not allow for simple black or white explanations. Geographer Matthieu Giroud, from the Paris-Est-Marne-la-Vallée university east of Paris, was particularly interested in the concept of social and ethnic mixing, an issue that is as manipulated by politicians as it is central to the rebuilding of a French society in which multiculturalism is not equated with the menace of communalism. And a society where social and urban barriers do not give a pretext to young French people to kill one another.

As Giroud wrote on the website La Vie des idées on November 3rd, ten days before he was killed, in words which have a particular resonance as it was the working class and gentrified areas of East Paris that bore the brunt of the attacks: “Social mixing, as a frame of reference for action or a activist and humanist principle, often leads to the control of the working classes and the way they take ownership of an area: a control that can lead to vigorous opposition from the latter ... The constant reference to mixing slows down redistribution or distorts it, and undermines those genuine measures that can be taken to reduce social inequality – such as those that would involve strict rent controls or an obligation to compensate people threatened with eviction at the true market value.”

What the November 13th attacks prove above all is the extent to which those who carried them out really understand us, right down to our habits and the divisions that they are striving to widen. It therefore remains essential to seek to know them better, to understand their motivations by trying to grasp the monstrous nature of their character without at the same time turning them into religious fanatics who are beyond our understanding. Indeed, French academic Olivier Roy, an expert on Islam, insists that what we are witnessing is less the “radicalization of Islam than an Islamisation of radicalism”.

It will certainly be difficult to confirm the estimates put forward by the investigating magistrate Marc Trévidic, who until recently worked on investigations into terrorism, who thinks that only 10% of jihadists head for Syria out of religious motivation. “Ninety percent of those who leave to wage jihad do so for personal reasons: to have a fight, for adventure, for revenge because they haven't found their place in society,” he said.

But it is clear that just looking at the issue from a religious perspective is not enough. The British journalist and writer Jason Burke, who has written about the appeal of jihad for Western youths, said in a recent interview with Swiss newspaper Le Temps: “What jihadists offer these young people is what the culture of 'gangsta rap' also offers. The images posted on social media from Raqqa or Mosul resemble rap: young people with guns looking dangerous. What distinguishes Islamic State from al Qaeda is that it offers sexual opportunities, marriage, even slaves. Al Qaeda imposed an enforced celibacy with a very strong probability for its members that they would die. Islamic State is different. Its Syrian base is much more comfortable, much more accessible and the communications there are much better than in the Pakistan-Afghanistan area.

“There are luxury cars in which the fighters adopt the classic pose of gangsters. They can also imagine that they're protecting the weak there or that they are obeying a religious injunction. Rather than having a relatively uninteresting life somewhere in Europe you become 'Abu Omar al-Britani' or whatever. You have a status that you'd never have got before. What's also very clear is that the Islamic State version of jihadism is very undemanding in religious terms. You have to give up virtually nothing, except perhaps alcohol. It doesn't demand anything very difficult in terms of religious training, the spiritual journey that the true faith demands. There is very little faith and spirituality in there.”

If the religious perspective alone is insufficient, we must also look at these acts from a political perspective, including the extreme violence that tends to mask them. And thus reply to them politically, not simply giving a military or security response. Following the Paris attacks President François Hollande has finally abandoned his adherence to the EU budget rules known as the “stability pact” in favour of the new self-styled “security pact”. When will we see the much more urgent “diversity pact” or a renewal of the “social pact”? When will there be genuine reflection over what we are doing now, over and above the bragging and the states of emergency, so that the concept of “France afterwards” - the France that develops after the attacks – does not simply become a hollow slogan?

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter